Mick from the cockpit. The beautiful Oxfordshire hamlet of East Hendred is not a place that you’d expect to be associated with epic rally endeavours or record-breaking, but a recent visit to Philip Young proved to be an education. The Endurance Rally Association team is based opposite a fine 12th-century church where Captain George Eyston OBE, MC is buried. “He’s in pole position right by the entrance,” revealed Young, “and Eyston is the only Land Speed Record hero to have a plaque inside a church.” The historic rally supremo was soon leading me into the nave and pointing out the brass wall plate. The inscription reads: ‘The choir benches were given in memory of the holder of the World Land Speed Record of 357.5mph in Thunderbolt 1938-26 June 1897-11 June 1979.’ East Hendred’s connections with the Eyston family go back centuries. Centre-stage in the village is the handsome family home, Hendred House, where George was born and where Thunderbolt – his long-lost twin-engined, 2350bhp LSR challenger – was once stored in barns. Close to the manor’s drive lies the Eyston Arms but, frustratingly, there are no photos inside of the valiant war hero and speed king.

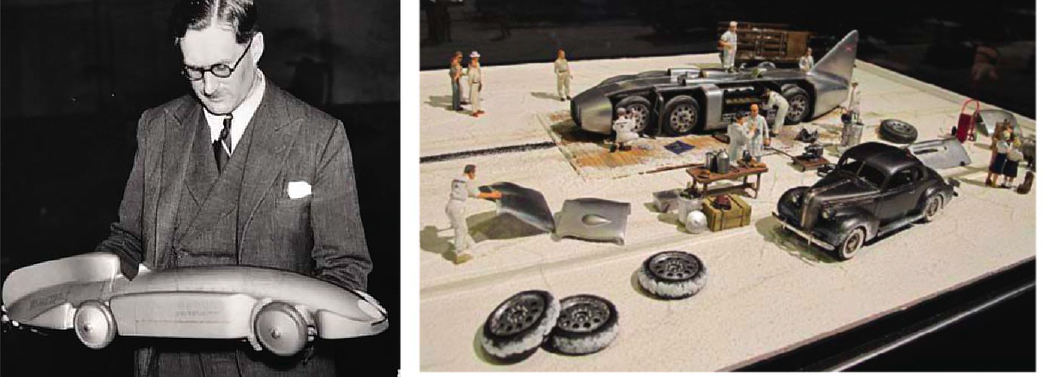

This towering figure with round spectacles and neatly clipped moustache looked more like a headmaster than a record-breaker, but there was no shortage of the right stuff, as he proved during the Great War. His engineering studies at Trinity College, Cambridge were interrupted by service with the Royal Field Artillery, where he was awarded the Military Cross for valuable reconnaissance duties, regularly going forward under heavy fire. Later, during WW2, he would help to plan the D-Day landings.

Eyston’s studies recommenced in 1918, when he also began racing motorcycles under a pseudonym; he twice rode in the Belgian GP at Spa before switching to four wheels with a GN. While at Cambridge, his interests ranged from sculling and sailing to experimenting with a radio aboard a Deperdussin monoplane. Riding on the footplate of the Bristolian locomotive was another of his memorable experiences.

Eyston raced an amazingly diverse range of cars, including co-driving ‘Tim’ Birkin’s Maserati 26M in the 1931 French GP, but at home his fearless battles in the 8-litre sleeve- valve Panhard monoplace were career highlights – particularly an epic duel with future LSR rival John Cobb’s Delage at Brooklands in 1932.

His interest in record-breaking was spurred by his friend Ernest Eldridge, the 1924 LSR holder who’d lost an eye when his Miller somersaulted at Montlhery. Eyston became a regular at the French circuit, where he claimed many records. During one night challenge for Riley, he had to share the track with an unlit motorcyclist who he made tie a torch to his back so that

Eyston could spot him. Even when bed-ridden with flu, he left his Paris hotel to take the world’s hour record in the Panhard.

Eyston’s greatest machines suffered sad fates. Thunderbolt was destroyed by fire in New Zealand, while Speed of the Wind was destroyed during a bombing raid on the Willesden works where it was stored. His distinctive 120mph AEC diesel-powered saloon survived the war but Eyston eventually sold it for £5 and it vanished.

Away from record-breaking, Eyston developed the vane-type Powerplus supercharger and was appointed a director at Castrol. Even in his 70s, he gained his seaplane licence and continued to enjoy fishing and shooting.

‘Eyston looked more like a headmaster than a record- breaker, but there was no shortage of the right stuff’

Another enthusiast fascinated by Eyston’s story is French model-maker Jean-Claude Baudier of Chrono 43. His latest masterpiece celebrates the legend’s Bonneville endeavours, and stretches across a white board replicating the salt flats. A team of mechanics is changing the tyres on Thunderbolt, while along the black guide-line at the far end a film crew waits patiently on the roof of a Ford V8 saloon.

With no preliminary trials, Eyston achieved 312.2mph in 1937, then 345mph in ’38, and with a closed nose and canopy pushed it to 357.5mph. Concerned about exhaust gases and fumes from the pioneering disc-brake lining in the revised cockpit, Eyston wore a respirator on the final run – again with no previous high-speed testing! If you visit the Eyston Arms, please enquire why there’s no photo of this hero.