Mr Brown’s boys the Aston DB story. As Aston Martin unleashes the DB11, Octane gathers together the most significant of the DB bloodline. Join us for celebration. Photography Matthew Howell and Alex Tapley.

When Aston Martin resurrected the DB badge in 1993, under Ford’s patronage, it was more than 20 years since it had last appeared. But such is the resonance of those initials that they instantly gave the DB7 an aura no amount of marketing hype could ever bestow. Sir David Brown himself was welcomed once more into the Aston Martin family, touring the production line with Ford eminence Walter Hayes and giving the project his blessing.

The DB badge was back on an Aston Martin and all was right with the world. Relatively speaking. Aston Martin’s entire history has been a rollercoaster ride that has somehow conspired to have more downs than ups, the company often teetering on the brink of insolvency. That said, the original David Brown era – from 1947, when the Yorkshire industrialist acquired the company, to 1972, when he finally bailed out – are still widely viewed as a golden age. The DB2 was the car post-war schoolboys (and their fathers) lusted after: a rakish fastback coupe with a lusty straight-six and Le Mans provenance. In many ways it set the template for everything that followed.

And what followed first was Aston’s ‘holy trinity’ of DB4, 5 and 6 – the models that turned Aston into Britain’s Ferrari, and Newport Pagnell into Britain’s Maranello. Such a trajectory couldn’t be sustained forever, and the DBS saw the magic begin to wane as Aston went in search of more sales in the US – yet, reworked as the AM V8, it would be the company’s lifeblood for the next two decades. And when it looked as though even Aston Martin could no longer trade on past glories, the DB7 sold in bigger numbers than every preceding model put together. It gave Aston Martin a future as well as a past.

The DB9, in turn, marked the start of the modern Aston era – a clean-sheet car that could be measured against the best without need for qualification or excuses. And now the DB11 heralds the next chapter. In the following pages we celebrate them all. Peter Tomalin

LOOK BACK NO FURTHER 1949-1959 DB2 to DB MkIII, by Peter Tomalin

So, why aren’t we kicking off this celebration of DB Aston Martins with the DB1? Good question. While the first production Aston under David Brown’s ownership is known today as the DB1, the name was applied only retrospectively: at the time of its launch in 1948, it was listed as the 2-Litre Sports. But that’s not the main reason why it didn’t receive an invitation. While the DB1 was not without merit, it had its roots in the pre-war era. It was also overweight and (under)powered by a mere 90bhp 2.0-litre four-cylinder engine, and was really more a tourer than a genuine sports car.

The DB2, on the other hand, was the start of something new, and a true sporting machine in the best Aston traditions. It made its first public appearance not on a motor show stand but at the 1949 Le Mans 24 Hours. It had low, lean, fastback bodywork that looked every bit as dashing as the Ferraris of the day. And in place of the DB1’s strangled old pushrod four it boasted an altogether more potent 2.6-litre twin-cam straight-six, originally developed at Lagonda. In fact, as many of you will know, so keen had David Brown been to acquire this engine that he’d bought Lagonda shortly after he’d bagged Aston Martin in 1947.

In 1953 the DB2 evolved into the DB2/4 – the green car you see here is an early example – with a raised roofline and the addition of two occasional rear seats whose backs could be folded fiat to create a larger luggage deck, reached via a hinged hatch (which, some contend, made the 2/4 the world’s first hatchback). The following year the engine capacity grew from 2.6 to 2.9 litres, and in 1955 a MkII version incorporated extra headroom and other small improvements.

1954 Aston Martin DB2/4 road test

The final development was the MkIII introduced in 1957 (Aston had by then dropped the 2/4 nomenclature), which brought another useful increase in power, further refinements and a more sophisticated look incorporating designer Frank Feeley’s ‘classic’ Aston grille.

All of these variations on the DB2 theme are known collectively as Feltham Astons, though in fact that’s somewhat misleading. It’s true that the DB2 was conceived and developed in the converted hangars of the old Hanworth Air Park in the west London suburb – but most of the chassis were assembled in Yorkshire, at the DB parent company’s tractor factories, while early bodies were built by Mulliners in Birmingham. And after David Brown bought the old Tickford coachworks in 1954, production slowly transferred to Newport Pagnell.

But ‘Feltham Astons’ remains useful shorthand for the models that preceeded the DB4. And the ultimate incarnation – certainly the most handsome to these eyes – was the DB MkIII. Look at this 1957 example, painstakingly restored by Aston Martin Works and simply fabulous in period Elusive Blue. Its proportions are beautifully judged, and you’ve got to love those twin exhausts – the ‘sports’ option – slung beneath the shapely tail with its delicate ‘cathedral’ lights (a feature that would be carried over to the early DB4s).

So what’s it like to drive? Just bear with me while I climb inside… The first thing that strikes you is that it’s like trying to insert yourself into an 8:10 scale model. Were people really so much shorter in the post-wary-ears? Maybe it was all that food rationing.

If you’re anywhere near 6ft tall, you’ll have to duck under the low door aperture and simultaneously twist your legs under the vast span of the spindly-rimmed wheel. Once you’re settled in the short-cushioned bucket seat, the shiny plastic rim of the wheel sits right in your lap, your legs slightly splayed, feet resting on pedals that are curiously offset to the right. Rotate your head to the right and your eyes are level with the top of the window- frame rather than the window itself. Diminutive David Brown no doubt fitted perfectly.

The view ahead, though, through the shallow, upright windscreen is quite wonderful, the dome of the bonnet and the curving wing-tops plunging away into the near distance. And directly in front of you is an impressive array of instruments set into a painted facia that echoes the shape of the front grille – a big improvement on the 2/4’s central dash and another feature that would be carried over to the DB4.

Turn the key and the already-warm 2.9-litre LB6 (that’s L for Lagonda and B for Bentley, for it was WO Bentley himself who oversaw its original design) catches quickly and settles to a rumbling baritone idle. In period, Aston Martin quoted 160bhp on the standard twin SU carburettors, as fitted to this car (another 16bhp with the twin sports exhausts, and 195bhp on triple Webers). On SUs, the 0-60mph time was around 10sec, the top speed 120mph, not that we’ll be putting either of those to the test today. This car is still in the custody of Works after its two-year restoration, last autumn it won the Feltham class at the AMOC concours, and the owner is yet to take delivery. I’ve sworn to treat it with due reverence – and Works’ Nigel Woodward is sitting alongside to make sure I’m true to my word.

Release the umbrella-handle-style handbrake under the dash to your right. The clutch, though meatily weighted, takes up progressively and there’s plenty of low-down torque to get you away smoothly. The four-speed David Brown gearbox is an easy-going companion, too – it has a conventional H-pattern and, although there’s no discernible springing to the third- fourth plane, the gate is widely spaced and the shift positive, so slotting each gear cleanly isn’t an issue.

As standard, the unassisted steering requires some serious heft at low speeds, this one is very sensibly fitted with discreet (and adjustable) electric power assistance, which takes all the sweat out of it. Better still, when the car’s up to speed, you can dial it right back. Some purists might scoff, but if it makes the car so much more driveable and useable, surely it’s a good thing.

The only aspect of the dynamics that I’m struggling with is the brakes. The MkIII has discs at the front whereas all but the very last 2/4s had drums all round, and Woodward assures me they give quite a bit more bite. I’m yet to find it. When you press the pedal there’s what feels like several inches of fresh air before you meet resistance, then a dead patch where nothing much happens at all. Finally, when you really push like you mean it, the front pads start to nip at those discs. If this MkIII were mine and I was planning to use it properly, I think I’d be tempted to have the brakes uprated, and hang the originality.

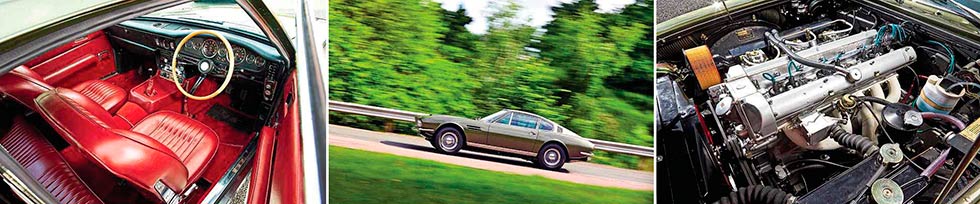

Above and right DB MkIII gave way to DB4, whose dashboard styling it pre-empted; Lagonda straight-six powered all DB2s and the MkIII.

TECHNICAL DATA 1954 Aston Martin DB2/4

Engine 2580cc straight-six, DOHC, twin SU carburettors

Power 125bhp @ 5000rpm

Torque 144lb ft @ 2400rpm

Transmission Four-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

Steering Worm and roller

Suspension: Front: double wishbones, coil springs, lever- arm dampers. Rear: live axle, coil springs, lever-arm dampers

Brakes Drums

Weight 1259kg

Performance Top speed 120mph. 0-60mph 12.6sec

‘The DB2 ‘made ‘its first ‘public appearance not on a ‘motor show stand but at Le Mans’

TECHNICAL DATA 1957 Aston Martin DB MkIII

Engine 2922cc straight-six, DOHC, twin SU carburettors

Power 162bhp @ 5500rpm

Torque 180lb ft @ 4000rpm

Transmission Four-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

Steering Worm and roller

Suspension Front: double wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers. Rear: live axle, coil springs, telescopic dampers

Brakes Discs front, drums rear

Weight 1338kg

Performance Top speed 120mph. 0-60mph 9.3sec

MICHAEL BAILIE PHOTO Aston 2-Litre Sports became known only retrospectively as DB1

Above and below. DB2/4 (green) lays claim to being the world’s first hatchback, and its styling evolved into the MkIII (blue): Aston 2-Litre Sports became known only retrospectively as DB1.

Because you really would want to use a car like this. The ride is good – it actually feels quite softly sprung, the tall sidewalls of the 185 R16 Avon Turbosteel radials doubtless playing their part – and, with overdrive on third and top, it’s reasonably long-striding, so cruising at the national limit or higher wouldn’t be an ordeal.

The longer you drive, the less it feels like a precious, four-wheeled sculpture and more like the robust and well- proven sports car that the Feltham Aston had become by the late ’50s. You also learn that, although there is a decent chunk of torque to draw on, as with any sporting machine, what it really thrives on is revs. It never quite sings like a pure race engine, but it does growl enthusiastic approval when you give it its head.

It’s just quick enough to be interesting; it makes all the right noises, it rides and steers acceptably well for the period, and it looks absolutely terrific. After a day spent in the company of the 2/4 and this very special MkIII, I’ve really warmed to these Feltham Astons – wherever it was they were actually built! In fact the last MkIIIs were built on the same line at Newport Pagnell as the early DB4s, the two overlapping by several months.

Of course, the DB4 was the more modern car: quicker, more refined, simply better. But the Feltham Astons thoroughly deserve their strong following. In several ways, the DB4 was a more exotic concoction – an all-alloy engine designed by an ex-pat Pole, Superleggera construction, bodywork sketched by suave Italians… The Feltham Astons were so British it hurts. Iron-blocked straight-six designed by Willie Watson under WO Bentley. Chassis designed by Claude Hill and built by Yorkshiremen; bodywork by Frank Feeley and constructed around part-timber frames in English coachworks.

And proper sports cars, too. When three DB2s were entered for the 1950 Le Mans 24 Hours, two of them finished first and second in the 3-litre class and fifth and sixth overall. The following year they went even better, claiming third, fifth and seventh overall and taking the first three places in their class.

No DB4, 5 or 6 ever did that…

REALLY, IT ALL STARTED HERE… 1958-1970 DB4, DB5 and DB6 by Andrew English

Proportions, power and price define this era of Aston Martin history, though anyone who has owned a DB 4, 5 or 6 might also characterise it as the epoch of crap handbrakes.

Certainly the sumptuous trio lined up at the start of Millbrook Proving Ground’s hill route are lookers in a way that nothing else here can hold a candle to. Of the three, it is the DB4, an earlier short-wheelbase car, that has the ‘golden proportions’ between body, wheelbase, bonnet and roofline. The other two have their moments, particularly the 5, which is classic thuggish GT in profile, but the 4 really has ‘it’. As for how it must have appeared at its launch in 1958: wow.

The cars everyone remembers Aston Martin by will always be the DB4, 5, and 6. Make that DB5, of course, thanks to a certain Commander Bond, to whom we’ll be returning. Actually, Bond’s first Aston was a DB MkIII Mi6 pool car in the Fleming books, but that’s an utter anorak’s detail.

So wave goodbye to the vintage, bendy chassis of the early DBs and that Willie Watson/WO Bentley LB6 engine with its horrible ‘cheese’ location of the bottom end. No time for cheese here, Daddio, we’re on the cusp of the Swinging Sixties.

Right and below. The DB4, 5 and 6 really begat the modern Aston Martin story. DB4’s Italian styling is hugely elegant, cabin a Boy’s Own thrill, big straight-six makes it a lusty performer.

David Brown, head of the eponymous industrial group, noted connoisseur of a well-turned ankle and Aston Martin’s owner, had laid out around £75,000 for Aston Martin and Lagonda in 1948 and, seven years on, he was about to see the fruition of his investment. Fresh into his second marriage to his secretary, Marjorie Deans, this sartorially impeccable boss could travel to Feltham in Middlesex and walk into the drawing office of his own car company to inspect progress on Development Project 114, with its perimeter-frame chassis and the Frank Feeley-influenced design. This was to be the DB4.

then, sauntering over to the engine design office, Brown might find his latest hiring, the talented Polish engineer, Tadeusz ‘Tadek’ Marek, hard at work on DP186, the new six-cylinder engine for that DB4.

This was a good year for the competition department, too. DB2/4s came first, third and fourth in class on the Monte Carlo Rally and on the track there were seven victories in International meetings, including second at the 24 Hours of Le Mans for the DB3S of Peter Collins and Paul Frere, and a win for Reg Parnell and Dennis Poore in the Goodwood Nine Hours.

1971 Aston Martin DB6, DB5 and DB4 driven

The winds of change were blowing at “The Aston”, however. David Brown was in negotiation to buy the Tickford coachworks in Newport Pagnell, with the intention of moving Aston Martin there. And the company was also planning to use a new construction technique for the DB4: Superleggera. This patented aeronautical body construction came from Touring of Milan and comprised a frame of fine steel tubes over which the aluminium coachwork was laid. John Wyer flew to Milan to finalise details of the new body, which would incorporate the nose of Feeley’s successful DB3S, but the Italians were adamant that it would require a platform chassis as abase, not a perimeter frame as used on DP114.

So in a mighty hurry, that car was dumped and Harold Beach set to work to design a steel platform chassis, which in recognisable form would underpin Aston Martins right up to the year 2000 and the last of the V8 cars. Front wishbone suspension and David Brown rack-and-pinion steering was salvaged off DP114, but that car’s de Dion rear end was replaced with a simple coil-sprung live rear axle and lever-arm dampers.

Marek didn’t want his engine to be made of aluminium, but the foundry chosen to cast the block had no spare capacity for cast iron, yet it could do the unit in aluminium. So Hiduminium, a Rolls-Royce developed high-strength alloy, was used for the cylinder block and head. It made for a (relatively) lightweight if rather large unit, but the greater expansivity of aluminium meant the twin-carb 3.7-litre engine was peculiarly vulnerable to overheating, as the engine would expand around its bearing journals and the oil pressure would fall to critical levels.

The DB4 was launched at the 1958 Earls Court Motor Show (you can see it on YouTube, Google ‘motor show 1958’ and skip to 1:14) alongside the new Rover P5 3 Litre. At £4000 (£84,297 in today’s values according to “The Bank of England” inflation calculator), the Series 1 DB4 was an expensive car. But not expensive enough, it would seem. Aston’s finances were always parlous. Gordon Sutherland, the company’s MD between 1933 and 1947 and the man who sold Aston to David Brown, once said that ‘saving Aston Martin was a re-occurring chore for all of its owners, but making money was optional’.

Brown had similar problems and, although the company was used as a halo marque for the whole David Brown Group, it’s unlikely it ever made money. In fact there’s an apocryphal story from the 1960s of when Hollywood actor Clark Gable toured the factory with David Brown. Afterwards he announced that he would like to buy an Aston but, because of the publicity value of his ownership, he wanted to pay just cost price for his car. David Brown brightened considerably, saying: ‘Oh, thank you very much, Mr Gable, most of our customers pay £2000 less than that.’

The rest of the story is pretty straightforward as each new version became better in some ways, more powerful and more comfortable, but heavier and less pure. The tale includes the 1961 Lagonda Rapide four-door saloon based on a modified DB4 chassis and, of course, the 1959 DB4 GT and the following year’s hugely influential if not- actually-that-successful Zagato version of the same. And then there were the Project cars, equally undistinguished on track, if lovely-looking and stentorian. Funny how, having won the 1959 World Sportscar Championship, Aston Martin seemed to forget how to win races.

By the time of the Series V DB4, the wheelbase had been stretched, the headlamps faired-in and the car was in effect a DB5. Considering its impact on little boys’ imaginations, the DB5 crept out with very little fanfare in the middle of 1963, and only 1021 were made, including 12 Harold Radford shooting brakes and 123 convertibles. The DB5 was the last Aston to be built using Superleggera construction it had 40lb ft more torque than a Series IV DB4, but weighed an extra 154kg.

At the end of 1965, the most practical version of the series was introduced, the DB6. Using a folded metal body construction, it weighed the same as a DB5 but had another 4in in the body and a Kamm tail to introduce greater stability at speed. In the five years to the end of 1970, Aston built a total of 1782 DB6s, its most popular model at the time. There were two versions, MkI and fuel-injected MkII, and total production includes 215 Volante dropheads, a series of Harold Radford shooting brakes and, as with the DB 4 and 5, a high-performance Vantage version.

Accepted wisdom is that the DB4 is the best to drive, especially when fitted with a three-carburettor 4.0-litre engine and decent oil cooler. It’s lighter, more responsive and more like a sports car. Tested by The Motor in 1961, a 240bhp, four-speed, non-overdrive, twin-carb DB4 weighing 1397kg and shod with Dunlop RS5 tyres delivered a top speed of 139.3mph, 0-60mph in 9.3sec, an overall 16.5mpg and the following verdict: ‘Performance, controllability and comfort have been combined in the Aston Martin DB4 to make it a highly desirable car: one in which long journeys can be completed very quickly indeed with the minimum of risk or discomfort and the maximum of pleasure.’

‘Accepted wisdom is that the DB4 is the best to drive, especially with a three-carburettor 4.0-litre engine’

TECHNICAL DATA 1961 Aston Martin DB4

Engine 3670cc straight-six, DOHC, twin SU carburettors

Power 240bhp @ 5500rpm

Torque 240lb ft @ 4250rpm

Transmission Four-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

Steering Rack and pinion

Suspension Front: double wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers Rear: live axle, radius arms, coil springs, lever-arm dampers, Watt’s linkage

Brakes Discs

Weight 1385kg

Performance Top speed 141mph. 0-60mph 8.4sec

The trouble with accepted wisdom is that it doesn’t tell the complete story. For a start, among the 3730 DB4, 5 and 6 models built, there will be few that have not been modified, tuned, completely rebuilt, restored or just kept going with whatever parts were available at the time. Then there is the ‘Bond factor’, which has pushed the prices of DB5s through the roof, and a lot of interestingly modified club road/racers have been converted into full- scale clones of the Corgi model in Silver Birch paint with full over-ridden bumpers, as these are perceived as having greater value. Add in the marginal practicality of these cars on today’s public roads and you end up with a slightly different view.

1971 Aston Martin DB6 road test

So what are they like to drive? The first thing that hits you is the smell, a distinctive mix of old car, leather, petrol and oil (the only wood in these Astons is riveted to the steering wheel). Aluminium and steel doors tend to shut with a flappy crash and you’re there in front of an instrument-festooned dash with an array of mysterious warning lights. Most cars have been fitted with quick- spinning modern starters, so pull the quadrant lever choke through its fast running are and into rich. A well-tuned car should start quickly and idle with that breathy, uneven bluster characteristic of all three cars.

The DB4 has a four-speed David Brown transmission, often with an overdrive and close- or wide-ratio gear sets.

It has it critics but, although it lacks a fifth ratio and the clutch is heavy, the change quality is light and direct and the Laycock de Normanville overdrive engages quickly. The ZF S5 325 five-speed is from a light commercial application and was fitted to most DB5 and 6s. It’s heavy, tough, noisy from new and has huge gears inside that won’t be rushed up or down. Second is impossible to engage when the ’box is cold, and the direct-feeling gate and knitting needle-like lever encourage delicacy and also get very hot. Nereis a three-speed Borg Warner auto option on later 5s and 6s, which is horrible.

So you’ve negotiated the fly-off handbrake and are underway with the steering twitching in your hands and your eyes admiring the view down the long aluminium pontoon wings as the engine’s considerable torque wafts you along. The ride quality is good, possibly over-soft, although a lot of cars carry a Harvey Bailey handling kit these days. Uprating the dampers helps to limit body roll and weight transfer, but it does make the car jiggly at the rear. All the engines have colossal mid-ranges and it’s a measure of their swept volume (there are a lot of 4.2- and 4.5-litre conversions out there), the cam timing and the carburettors how much it is worth revving them hard. Later DB6s are more docile, with better torque characteristics. They’re fast like a gathering storm, one push of the long-travel accelerator pedal and the addictive roar fills the cabin (particularly on DB4s with fewer silencers) and the scenery fast fills the narrow, curved ’screen as white needles dance behind their glasses.

1961 Aston Martin DB5 road test

Most contemporary reports talk of the understeer, but that’s not fair. Driving one of these cars is much about planning and vision. You need to determine where you want the car on the road and put it there. Neither model will turn-in on a sixpence and, if you try, they’ll feel like a runaway train. You have to ease it into the turn and then accelerate through, tweaking the steering as the tyres move around. It’s a class act and a friendly one, mostly. Drive it hard on the right tyres and it’ll four-wheel drift through a turn and, being long and relatively narrow, the rear will slide wide, but it’s predictable and recoverable, though heavy.

Like with most Astons, tyre choice is crucial. The current crop of Avons CR6s is brilliant, Michelins XWX and Pirelli Cinturatos are good, but ultra-modern covers won’t suit the steering and 205 is about the maximum width you can go as they’ll foul the wheelarches on a 4 or a 5 unless they are relieved. The brakes are good, powerful with good feedback at the pedal, especially with the greater pad area of the Girling system fitted to 5s and 6s, but if the car isn’t used regularly or the fluid hasn’t had an annual change, the twin Lockheed servo system can activate with a disconcerting double-tap.

What none of these Astons is particularly brilliant at is traffic or narrow, poorly maintained roads. The steering is heavy unless it has a powered system, the secondary ride is firm and the car feels vulnerable, especially the very expensive body panels against other traffic and hedgerows. You’ll not see too many DBs with wing mirrors, as people brush against them and bend the panels they’re mounted on. In traffic the heat build-up is phenomenal, and you sit watching the temperatures rise while the smell of hot metal fills your nostrils. Using the heater in traffic is an old but stifling dodge, but a fair number of owners fit air-conditioning.

1965 Aston Martin DB4 road test

By 1970 the last DB6 MkIIs were being produced alongside the next breed of Aston, the DBS, and the former looked distinctly old-fashioned in comparison. Road tests complained about the DB6’s lack of creature comforts compared with contemporary Jaguars, and David Brown was forced to authorise discounts in order just to shift stock.

The world didn’t seem to value the aristocratic but quite different feel of the older-style DBs, which rewarded acquaintance and skill and were terrific driving machines as well as gran turismo mile-eaters. Today’s insane values mean you seldom see a DB4, 5, or 6 on the road now as they’ve become hoarded investment pieces, which is also sad as it means there isn’t a new generation of drivers learning to love these rare and beautiful cars.

TECHNICAL DATA 1965 Aston Martin DB5

Engine 3995cc straight-six, DOHC, twin SU carburettors

Power 282bhp @ 5500rpm

Torque 280lb ft @ 4500rpm

Transmission Five-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

Steering Rack and pinion

Suspension Front: double wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers Rear: live axle, radius arms, coil springs, lever-arm dampers, Watt’s linkage

Brakes Discs

Weight 1503kg

Performance Top speed

143mph. 0-60mph 8.1sec

TECHNICAL DATA 1971 Aston Martin DB6

Engine 3995cc straight-six, DOHC, triple Weber carburettors

Power 325bhp @ 5750rpm

Torque 290lb ft @ 4500rpm

Transmission Five-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

Steering Rack and pinion

Suspension Front: double wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers. Rear: live axle, radius arms, coil springs, lever-arm dampers, Watt’s linkage

Brakes Discs

Weight 1550kg

Performance Top speed 148mph. 0-60mph 6.5sec

Right and below A certain Silver Birch DB5 is probably the most famous car in the world; here one leads the trio, with DB6 in the middle, showing off its Kamm tail.

THE NEW ERA BEGINS 1967-1990 DBS – and beyond, by Andrew English

So where did the S in DBS come from? Lively correspondence on the Aston Martin Owners’ Club forum includes suggestions that it was for Saloon, Sports or maybe even Susan. The last seems most unlikely but Sport is probable since the very first DBS concept, designed and built by Touring of Milan and displayed at the 1966 London Motor Show, was a two-seater.

Using a cut-and-shut DB6 chassis, with an engine far back in the chassis, the first DBS was the Italians’ bid to be given the contract to design a DB6 replacement. Aston Martin wasn’t playing, however, and the job went to Newport Pagnell’s own seat designer.

William Towns hadn’t really had a big automotive design job by the time he came to Aston Martin. His talent was self-evident, however, from the first glance at the DBS clay model. Using the DB6 chassis as a basis, the width was increased by 4 ½ inches, the wheelbase by one inch, overall length was reduced by 1 ½ inches and height by 1 ¾ inches. If by today’s standards a 15ft long, 6ft wide car isn’t that big, in 1967 it was gargantuan – yet the DBS had a delicacy and attention to detail that passed the test of time, more than 20 years until the arrival of the Virage.

With new rear slip joints, the de Dion rear axle could be pressed into service, which suited the wider tyres of the time. Since Tadek Marek’s new V8 engine wasn’t ready, the old 4.0-litre straight-six was used, breathing through a trio of two-inch SUs to deliver about 280bhp at 5500rpm. From new the DBS cost £5800; according to the Bank of England calculator that’s about £94,960 in today’s terms.

There weren’t many road tests of this car, of which 900 were built, but Motor’s test team got their hands on one in 1969. This was the start of the sideways style of weekly road test, so it includes a picture of EPP 8G being luridly opposite-locked. Dealer HR Owen took an ad on the facing page illustrated with a pretty girl in a tied-up shirt and bikini bottoms lying on the bonnet – all together now, in the style of Swiss Toni: ‘Driving an Aston Martin is like making love to a beautiful woman…’

You’ll get the general idea of what they thought, however, with the stand first: ‘S for “superb’’’. The test car was in 290bhp, Weber-carburetted Vantage form (a no-cost option), weighed 1717kg with half a tank of fuel, and made a 141.5mph average top speed at the Motor Industry Research Association’s test ground near Rugby, with 0-60mph in 7.1sec (the same as they wrung out of a DB5).

‘A connoisseur’s four-seater GT devoid of fundamental faults: great performance and handling, despite immense weight,’ they wrote, but they didn’t like the tiny boot, cabin noise, defects in switchgear or the running costs.

They’re right about the switchgear, which looks thrown against the leather facia of this test car: a radially marked Smiths revcounter, seven separate dials, a flicking ammeter, a bouncing speedometer, nine warning lamps and a period LW/MW Radiomobile. Olive-green coachwork is superb, however, and the engine, crisp and fresh from a rebuild, woofles and warbles. With a ZF five-speed and Vantage-spec engine, the performance and driveline behaviour are much like the later DB6’s, but dynamically the DBS is very different. It rides so well, especially at the rear, where the damping is softer, but without the weight transfer and squat of the solid rear axles that had gone before. The rear tyres also grip better, so you are able to use more of the performance for more of the time. Adwest power-assisted steering is terrific; not accurate in a modern idiom, but progressive and well-weighted. On period 205mm-wide Pirellis, the front wanders on poor surfaces and corkscrews over bumps if you push it, but the feedback is faithful and confidence- inspiring. That width, however, is intimidating and, if you add in the considerable extra weight of the DBS, you are constantly aware that this is an awfully big motor car to be throwing around on a public road.

Marek’s 5.3-litre V8 was finally fitted in 1970 and the car was renamed the DBS V8. At 240kg, the V8 engine was only 14kg heavier than the six-cylinder, but the overall kerb-weight had increased to a claimed 1722kg (1753kg with 50 miles-worth of fuel in the 1971 Motor test). Better was a power output of 325bhp at 5000rpm from the engine the car had been designed for, and the superlatives didn’t stop. ‘Ultimate Performance,’ ran the headline on Motor’s road test, complete with glamorous brunette at the wheel. Top speed was 160mph, 0-60mph came in 5.9sec – even the price of £9000 wasn’t seen as a major drawback.

Now, though, we need to recall the dire situation Aston Martin was in. Facing increasingly poor finances and plummeting sales, David Brown sold out in 1972 to Company Developments Ltd, a Birmingham-based firm of businessmen, chaired by William Wilson, for just £100.

The world breathed a sigh of relief, reported a cheerful Motor magazine, which proved to be rather premature. One version of history suggests that Wilson’s tenure rebuilt finances, launched two models and kept Aston ticking over through a self-made crisis, a world recession and an oil-price shock; another speaks of don’t-care asset stripping, falling quality and a lack of investment.

Two years later, in December 1974, the company was in receivership. As 10,000 Aston Martin owners ruefully considered the future for their cars and the newspapers reported that James Bond’s company car builder was going bust, Walter Cronkite of CBS News delivered a eulogy to Aston Martin in a black tie, and children (including me) sent in pocket money to save the company.

The V8 model, of which only 402 had been built in two years, was suspended and Company Developments launched a ‘budget Aston”, the AM Vantage, which resurrected the old straight-six. Even priced at £2000 less than the V8 model, only 70 were sold.

In 1976 Peter Sprague and George Minden raised £1.7 million and bought Aston Martin. I met Sprague in London some years ago. He’s a brilliant raconteur and his memoir, Swift Running, is superbly entertaining. What he found at Newport Pagnell was a demoralised workforce and eye-popping working practices.

‘We found that one craftsman with great care was welding a bracket onto the frame,’ he wrote. ‘An equally fine craftsman was removing the same bracket with equal care three stages down the production line, about 40 feet away. They had tea together every day. No-one knew what the bracket had ever been used for.’

These were the ‘Curtis Years’ during which, under managing director Alan Curtis, William Towns’ advanced Lagonda four-door limousine was launched to great fanfare and the Oscar India, a much-modified V8 car, was relaunched. By 1979 Town’s shape was in its 12th year and Motor tested a £22,999 AM V8 automatic, capable of 145mph and 0-60mph in 7.5sec. Total production of V8 models had topped 1000 and the company was making six cars a week, which was remarkable when you consider they cost four times the average annual salary.

A year after that test Alan Curtis met Victor Gauntlett at a Stirling Moss benefit at Silverstone sponsored by Pace Petroleum, and Aston was on the move again. In 1980 Gauntlett purchased a 12.5% share in the company for £500,000 and Aston was about to enjoy a period of impoverished stability with funding from Peter Livanos. Where the AM V8 had romped through four model series under the previous owners, Gauntlett presided over just one model change in his seven-year tenure.

Gauntlett even rekindled a relationship with Eon Productions and Commander Bond. His personal pre-production Vantage model was used by Timothy Dalton in The Living Daylights (1987). In the same year a chance meeting with Walter Hayes resulted in Ford taking a shareholding in the company. Gauntlett stayed for another two years and for the launch of the Virage, which was produced alongside the last Towns V8 models and marked another new beginning for the company.

As a legacy of this period, the earlier DBS V8 is perhaps the best of the Towns models, though personal favourites of mine are the X-Pack cars, rare 408bhp monsters offered from 1986 until the end of production (only 131 of the 534 Vantage models built had X-Pack modifications), with Cosworth forged pistons and modified cylinder heads similar to those used on the Nimrod racing cars.

That bombastic exhaust note reminds me of Gauntlett himself, bellowing defiance at the world in general and speaking of a time when roads were quieter, oil was going to last forever – and so was Aston Martin…

“As a legacy of this period, the earlier DBS V8 is perhaps the best of the Towns models”

TECHNICAL DATA 1970 Aston Martin DBS

Engine 3995cc straight-six, DOHC, triple Weber carburettors

Power 290bhp @ 5500rpm

Torque 290lb ft @ 4500rpm

Transmission Five-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

Steering Power-assisted rack-and-pinion

Suspension Front: double wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers. Rear: de Dion axle, coil springs, telescopic dampers

Brakes Discs

Weight 1707kg

Performance Top speed 141.5mph. 0-60mph 7.1sec

REMAKING HISTORY 1994-2016 DB7 and DB9, by Glen Waddington

It’s significant that there has never been a DB8. In 2004, Aston Martin stated that the nomenclature might confuse buyers into thinking that such a thing would be a V8-engined car, or that it might even be confused with a certain XK8. Equally, it was keen to put some distance between the two generations: DB7 and DB9. The newer car would be something of a step-change from the old. A landmark, even.

In fact, we’re talking about two hugely significant cars for the fabled marque. A marque that, in either case, could no longer be shorthanded as ‘Newport Pagnell’. Today we know that location – Aston Martin’s base since 1954 – as the home of restoration, maintenance and sales operation Aston Martin Works. Since 2007, no new Aston Martins have been built there. Neither of these cars were, either.

And that’s because, with the DB7, Aston Martin moved into the era of series production. Many were tempted at the time to label it ‘the baby Aston’. And sure, with talk of a ‘baby Bentley’ that eventually manifested itself as the Volkswagen-based Continental GT in 2003, there was excitement that Aston Martin would be building a more affordable, more widely available, more relevant car. Only it arrived well ahead of that Bentley, back in 1994.

Above. Two generations, a decade apart in age, a lifetime apart in conception – yet both were equal landmarks in Aston Martin history.

And at a time when the bespoke, Newport Pagnell-crafted Virage cost £133,574 (or £177,600 in souped-up Vantage spec), the new DB7 came in at £78,500. Some perspective? The base-model Porsche 911 Carrera 2 was priced at £54,995. And yes, we’re talking about the air- cooled 993 generation. The ‘baby’ Aston cost baby Ferrari money, and Car magazine lost no time in putting them up against each other on the cover of its December 1994 issue, even if the archly conservative Aston – more GT than sports car, with its front-mounted supercharged straight-six, coupe coachwork and rear-wheel drive – had little in common with the mid-engined, flat-crank V8-powered F355. No, the point was to celebrate the fact that Britain had developed such a compelling car that it could even be mentioned in the same breath as Ferrari’s cost- rival. While the Ferrari was always going to be the better driver’s car, the Aston was praised as a superball-rounder.

‘Aston Martin was looking back over its heritage in order to steer a path to its future ’

The name is a clue. Aston Martin was looking back over its heritage in order to steer a path to its future, and nothing better epitomised the kind of car Aston Martin wanted to replicate than the DB-series so fondly remembered from the 1950s and 1960s. You need only read what Andrew English says on pages 76-82 to understand why. The new Aston Martin would be a suave six-cylinder coupe packed with British charm. Just like the old DB4, 5 and 6. A James Bond car for the Pierce Brosnan generation. Only this time there would be more of them: when production ceased in 2004, more than 9000 DB7s (including convertible Volantes from 1996 and 200 special-bodied Zagato versions) had been built. That’s more cars than Aston Martin had built in the preceding 81 years of its entire history.

The one in these pictures is a later car. While it shares its body styling (a story in itself, which we’ll come back to) and Jaguar XJS-based underpinnings, this one packs a V12 punch. A 5935cc V12 manufactured within Ford’s Cologne engine plant especially for Aston Martin, launched in the DB7 Vantage in 1999.1 remember when they were new, driving one with a heavy-handed six-speed manual gearbox, but this example has the more commonly spec’d five-ratio auto, with a ‘Touchtronic’ function(slide the selector to the left for ‘up/down’ operation or use the ‘plus’ and ‘minus’ buttons on the steering wheel).

With 420bhp on tap, there’s clearly no shortage of urge, as well as a charismatically multi-layered voice. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. What of the interior ambience? Well, it’s very 1990s in here, but also extremely plush. Leather covers everything, and there’s much wood too, since all those V8s and Vantages of the 1980s apparently sealed that scene into Aston Martin’s DNA. But whereas Aston interiors used to be shaped according to the characteristics of the materials they were made from, this one swishes and swoops like so many mass-produced cabins of that era. Even more so: few cockpits are as voluptuous as this.

2003 Aston-Martin DB7 road test

Clearly Ford’s hand is at play in the switchgear department, but it’s really the clunky Jaguar-sourced air-con controls that are the biggest offender, and the attempt to integrate Ford Scorpio air vents into the door trims lacks, well, integration. This late car’s Mazda MX-5 door releases have been disguised with chromed pull-flaps.

There’s a bit of Mazda outside, too. Remember the five-door 323F? It donated its tail-lights, cunningly shrouded here to make them look less rectilinear. But bits pilfered from around the old Ford empire are only part of the story. Ford’s British-born PR supremo Walter Hayes brokered a deal with Aston Martin boss Victor Gauntlett (in charge since 1981) that saw Ford take full control in 1991. Hayes became chief executive and immediately appointed Sir David Brown (the man behind those initials) as honorary life president of the marque.

Aston Martin’s future, as so often, had otherwise been bleak: this company, limping along while handcrafting leviathans whose underpinnings and V8 engines could be traced back back beyond the DBS on the preceding pages, was producing cars in annual quantities of tens and hundreds. It barely registered with Ford executives. So Hayes hatched a plan that would revolutionise its fortunes.

The DB7 took a stillborn Jaguar project (the ‘F-type’, or XJ41 and 42 internally), agreed to Tom Walkinshaw Racing’s supervision of its development on XJS underpinnings, let loose Ian Callum (yes, Jaguar’s design director since 1999 but with TWR then and formerly of Ford) over its hard points to make it look suitably Aston and, ultimately, began production in the Bloxham, Oxfordshire, factory where Jaguar’s XJ220 had been built.

All previous Aston Martins had been aluminium-skinned; the DB7 broke tradition not only by having a steel monocoque, but by being based on a Jaguar.

So this near-two-tonne GT ran on the fabled independent suspension system that made the E-type such a storm and the XJ6 and XJS such fabulously refined cars to drive, though it was re-engineered in detail, especially in its geometry. Furthermore, power came from a Jaguar engine, the 3.2-litre AJ6, though with remachined block and heads, new cams, valves and pistons, and an Eaton M90 supercharger like the Jaguar XJR’s but running 40% more boost. Tom Walkinshaw obviously worked hard with what he had, though he’d envisaged a Jaguar-based V12, while Hayes had opted for the straight- six’s link with past Astons.

In the end, of all the DB7s built, only 2461 ran the straight-six. It’s a brawny device and doubtless most buyers were sold on the looks anyway; certainly, Ian Callum is on record as having said that looks were more important than handling, so long as the car drove well enough. But the V12 arrived in 1999 and almost immediately supplanted the six. It clearly struck a chord, and it appeared again in 2001’s V12 Vanquish, another Callum design, but this time from a clean sheet of paper. More than 2500 of those were built (with an aluminium/carbon composite body on a bonded chassis) at Newport Pagnell during a six-year career that saw the old Virage and Vantage replaced and thereby bridged the gap between Aston Martin of old and what we have today.

And what we have today is a V12-powered GT that has carried on the DB nomenclature. The DB9 may not be long for this world (the future appears in the next few pages) though I can see it further round the test track – only I can’t catch it. The DB7 Vantage is quick, no doubt, but it feels hefty in these tight corners, and the steering, though tactile, is rather slow-witted when you’re driving with commitment. The five-speed sludge-pump auto is a smooth ally when cruising but slow to change on demand, and the shift buttons on the (Fiesta-sourced and lightly tarted) steering wheel are in exactly the wrong place, so you can change gear by accident when properly tanking round a bend. As I’ve just found out.

2015 Aston Martin DB9 road test

Turn down the wick and the DB7 Vantage charms more. Powering around a test track is not its forte – and nor was it ever meant to be. Fact is, Aston Martin probably would not exist today had it not been for the huge return the company got on what was modest outlay for developing a new car. It was more successful than Hayes and co could have dreamed of. But what if the company could build a brand new replacement – a proper Aston Martin – that was just that little bit more sporting?

Enter the DB9. Sure, it’s a step-change. Revolutionary in its construction, for a start, with a Lotus Elise-like extruded aluminium matrix structure clad in aluminium body panels. The double-wishbone suspension was new, and the gearbox (six-speed, automatic or manual) rear- mounted for better weight distribution.

And it’s so much sharper, more modern, in its styling – though clearly a relative of the DB7. As many years have passed now since the DB9 was launched as there had been between then and the DB7 being unveiled, yet the DB9 hardly seems to have dated. Aston Martin referred to it as ‘a contemporary version of classic DB design elements and characteristics’; I’ve always thought it was beautiful, personally, possibly the most beautiful car ever, especially the original version as launched. Those gorgeous lines, finished by Henrik Fisker after Callum left for Jaguar, were subtly revised in 2012 (mainly the bumper graphics and outer sills, rather than expensive-to-tool metalwork) and the latest version of that same 5935cc V12 fitted, slightly lower in the chassis, so the 2015 DB9 you see here has a more fully fledged 510bhp.

Pop the doorhandles (flush-mounted bespoke alloy spars) and allow the door to glide out and up, then lower yourself and become ensconced in a world of leather and aluminium. Less obvious use of wood; a design language that has become over-familiar in the last few years, yet remains elegant. Still some old Ford empire bits, but nothing too obvious: the Volvo-sourced electric mirror switch pack is just like that used on some Jaguars.

You sit low, so much lower than in the DB7, which had a fixed-height perch and a steering column that would adjust only in rake. Here you get to play Touring Car drivers, so I slam the seat, drop the wheel and pull it chestwards, then punch the key (sorry, ‘emotion control unit’ – no, I don’t either) to hear the V12 erupt. Boy, it sounds the business here, so much harder-edged yet also fuller, more sparkly, and it revs higher too, with peak power at 6500rpm rather than 6000.

There’s yet more to adjust, not only traction control but also a Sport setting for the exhaust and throttle map, plus a harder damper setting. Yet the ride is firm enough, and the test track is bumpy in many places, so I opt for suppleness, hit the crystal ‘D’ button halfway up the central console and power away to devour a few corners. Which the DB9 will do, with far greater alacrity than the car that went before – though it wasn’t always thus. The earliest cars were not quite so well-honed (nor as powerful; they arrived with a 450bhp development of the DB7 engine, and a six-speed paddleshift version of the ZF auto-box) but this car represents a breed that has benefited from more than a decade of development – all carried out at Aston’s premises in Gaydon, Warwickshire, home since 2003. Ford bailed out three years later, and in 2007 Aston Martin was rescued by an investment consortium led by Prodrive founder David Richards.

The DB9 is fabulous. You can drive it hard, enjoying still-feelsome yet quick-witted steering, shifting gears with surprising responsiveness, enjoying a ride that’s tied down yet never harsh, and revelling in the glory of that growling, wailing V12. It sounds as good as it looks.

There have been other developments, not least the DBS version that acted as a bridge between two generations of Vanquish, plus, of course, a stunning drop-top Volante. But time is up. The DB9 is today’s car and tomorrow looms already. Can Aston Martin make a better DB than this? Turn the page.

TECHNICAL DATA 2003 Aston Martin DB7 Vantage

Engine 5939cc V12, DOHC per bank, 48-valve, electronic fuel injection and engine management

Power 420bhp @ 6000rpm

Torque 400lb ft @ 5000rpm

Transmission Five-speed automatic, rear-wheel drive

Steering Power-assisted rack-and-pinion

Suspension Front: double wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar. Rear: fixed-length driveshafts, lower wishbones, twinned coil springs and telescopic dampers

Brakes Discs, ABS

Weight 1780kg

Performance Top speed 185mph. 0-60mph 5.0sec

TECHNICAL DATA 2015 Aston Martin DB9

Engine 5939cc V12, DOHC per bank, 48-valve, electronic fuel injection and engine management

Power 510bhp @ 6500rpm

Torque 457lb ft @ 5500rpm

Transmission Six-speed paddleshift automatic transaxle, rear-wheel drive

Steering Power-assisted rack-and-pinion

Suspension Front and rear: double wishbones, coil springs, electronically adjustable telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar

Brakes Vented discs, ABS

Weight 1785kg

Performance Top speed 183mph. 0-60mph 4.6sec

Above: Ian Callum sought inspiration from the DB5 when styling the DB7 (green), and clearly remembered it when he began work on the DB9.

TOMORROW NEVER DIES 2016 – and onwards DB11, by Jethro Bovingdon

What an unforgettable day. The noise of barrel-chested straight-sixes fluffing and spluttering at low revs and then roaring and growling into life as the hungry carbs find the perfect blend of air and fuel, the delicate sensation of the DBS snicking cleanly between gears, the air thick with the sickly sweet smell of hot oil and burned hydrocarbons, forearms tingling from the exertion of aiming a DB6 MkII through the endless sweeps and banked turns of this amazing test track. These are the snapshots that will live long in the memory. Gathering these extraordinary cars in one place was a mighty headache (thanks Mr Lillywhite!) but it was worth every favour called in, every bead of sweat and every second spent negotiating with insurers. The textures, feelings, noises and smells are pure seduction and utterly corrupting. And I don’t know about you, but I could just stare at the DB4 all day, every day. Forever.

In the midst of the beautiful din, the elegantly scribed lines and the dazzling quality of cars provided by from Aston Martin Works, there’s a new shape. Ice cool, lithe and yet seemingly cut from pure muscle, low and menacingly wide but with a lightness of touch that creates an impression of effortless power rather than obvious aggression. The DB11, the final chapter of this story (so far) and yet another fresh start for Aston Martin, feels absolutely at home in this celebrated company.

2016 Aston Martin DB11 road test

It’s fascinating watching the other writers, photographers and designers as the cover shot slowly comes together and the cars sit in close quarter. Most are drawn to the DB4 or DB5 first, then the surprisingly clean and tightly tailored DBS diverts them away… but soon each one ends up pacing up and down beside the DB11. After a minute or two looking and pondering, most begin to run a hand along that great sweep of aluminium that makes up the roofline. A hesitation around the halfway point, then there’s a little glance around before the door is swung open and they drop behind the steering wheel. Seconds later there’s a smile as wide as the classic DB grille that’s been stretched and teased into its modern form at the front of this car. The DB11 isn’t retro and it certainly isn’t simply a mild evolution of the DB9 shape that’s become so familiar, but it seems very much to have the Right Stuff. Finished in Lightning Silver, it’s pure, dramatic and wonderfully sculptural.

To day the DB11 is, frustratingly, little more than a prop. My dynamic assessment of the car was some time ago on a test facility near Rome. It wasn’t Lightning Silver. In fact, it was covered in black and white swirls, a bit frayed around the edges and the interior rattled with diagnostic equipment. Yes, it was a prototype. Aston Martin said that it was around 85% finished in terms of suspension tuning and drivetrain calibration and also said we shouldn’t drive the finished DB11 here today because you’re reading this story a full two weeks before the embargo for final driving impressions. As an aside, the man from Aston Martin left at lunchtime.

2016 Aston Martin DB11 road test – Far left and bottom left. All change outside and in, with a more sculpted shape than the DB9’s and new Mercedes- sourced control interfaces. Still lashings of leather, though.

Prop or not, it’s fantastic to see the DB11 alongside its predecessors. Even better to hear its new twin-turbo 5.2-litre V12 as it’s shuffled about for photography. It is the mightiest DB ever, that’s for sure. The engine has a deep, complex note familiar from the DB9 and hides its forced induction well, but the numbers are way beyond anything else here. It produces 600bhp at 6500rpm and 516lb from just 1500rpm all the way to 5000rpm. That’s more power than a DB4 and DB5 combined and it pushes the DB11 to 200mph and from rest to 62mph in 3.9 seconds, here’s no satisfying, accurate manual ’box but the eight-speed ZF automatic gearbox promises speed and serenity and the DB11 also benefits from a limited- slip differential and torque-vectoring by braking to increase agility and help disguise its 1770kg.

When you first sink down into the DB11, the technology behind it, the controversial switch to forced induction and the new tie-up with Mercedes-Benz all seem suddenly less important. Somewhere deep in my subconscious I know and appreciate its new, lighter, stiffer aluminium tub, that it’s suspended by double wishbones at the front and a new multi-link arrangement at the rear. I suppose the touchpad and rotary controller mounted on the central tunnel register as familiar from the AMG GT S (or even a C-Class W205, come to that), too.

But while the much more intuitive Mercedes-Benz-sourced control system will make the DB11 a fine ownership prospect, I’m still in the honeymoon phase. Swooning over the huge veneers on the doors, the central display that’s hollowed-out like the hull of a hand-finished boat, and the fine leather trim that covers every surface. I’m not sure about the slightly fussy angled side air vents, and the squared-off steering wheel looks a bit unnatural. Overall though, it feels, smells and looks special. The good vibes continue when you press the big glass starter button and the huge central revcounter lights up.

Press the D to the right of the starter button or simply pull an upshift paddle and you’re ready to go. It takes barely 100 yards to know the DB11 is a very different beast from the DB9. The ride is quieter and more supple, the engine has good response and masses of torque, the gearbox is quicker, but most of all the new DB11 feels smaller, lighter and much more agile.

The key is a new steering system that’s vastly quicker than before. Gone is the DB9’s hydraulic rack with a 17:1 ratio, hefty weighting and that lovely gravelly texture that communicated so clearly. Instead the DB11 has an electric power steering system that’s smoother, lighter and faster. The ratio has fallen to just 13:1 and the result is that this big GT loves to change direction. There isn’t the almost disconcerting edginess found in a Ferrari F12 but after the DB9, and in even starker contrast to the older DBs, the new car’s pointiness takes some adjustment. Steer with your wrists, not your forearms and shoulders.

Of course, the body control of DB11 is on another planet to the older cars, which rock and roll with every braking and steering input. Despiteex-Lotus engineer and now Aston chief test driver Matt Becker’s fanaticism about ride comfort (drive an early Evora and you wonder how any sports car can ride with such grace), the DB11’s chassis is beautifully in tune with the responsive front end. You turn, it responds, front and rear working as one. It employs Bilstein’s latest Skyhook dampers with three settings – GT, Sport and Sport +- giving a wide operating range, here’s a marked step between each but even in Sport+1 think the ride is a little more fluid than the DB9’s. For me Sport seems about perfect, giving the chassis the support it needs to suppress roll and pitch but never descending into harshness. These settings will be further polished in the production cars but, despite its tatty appearance, the most incredible thing about the prototype is how cohesive it all feels.

2016 Aston Martin DB11 road test – Below. 5.2-litre V12 is a smaller-capacity evolution of the existing 6.0-litre – twin turbochargers more than make up the difference…

Mirroring the toggle switch for the suspension is another on the right spoke of the steering wheel. This one also flicks between GT, Sport and Sport+ modes but it acts on the drivetrain. GT offers relaxed throttle response and silken shifts, Sport ups the ante and Sport + introduces upshifts that nearly match the best dual-clutch gearboxes and ramps-up engine response, too. As you can tell, there’s much to experiment with and optimise for your own tastes, but, while initially it might seem a bit complex, I’m sure after a time you’d hit upon one preferred motorway and city setting and one for pure enjoyment. On a closed test track I like Sport for the chassis, Sport+ for the drivetrain (those shifts are addictive) and finally Track mode for the traction and stability control systems, which is activated through the menu system.

‘The DB11 simply flies around the test track. It sounds glorious, all big-lunged V12 and almost no turbo chatter’

So configured, the DB11 simply flies around the test track. The engine is so strong and, unlike some turbocharged units, it offers real reward if you rev it right out. It sounds glorious, all big-lunged V12 and almost no turbo chatter or whistle. Remarkably, considering the sheer stonk on offer from little over tickover, the rear 295/35 ZR 20 Bridgestone S007s offer excellent traction and only succumb to the torque with real provocation. Here the Track mode for the stability systems is fantastic, as it allows you to feel the DB11’s tail start to swing but seamlessly catches any slide before it gets out of hand. Perhaps there’s more body roll than in the (more extreme, more expensive Ferrari F12) and it certainly doesn’t have the grip and absolute control of a new 911 Turbo 991.2, but the weight transfer helps telegraph exactly what the DB11 is doing. Soon enough the steel brakes are groaning slightly in protest but they stand up to the test manfully.

The electric power steering can’t quite match the information that pours back through theDB9’s wheel, but still its weight shifts with surface changes and as the tyres start to cry enough. Go looking for the limits and you’ll find mild understeer on corner entry and then a little flourish of oversteer on the way out. Controlled, predictable, hugely exploitable. More often you’ll just enjoy the agility and rippling performance. Even in prototype form the DB11 promises to deliver a level of refinement, control and excitement beyond the DB9.

No doubt, there’s much still to learn about the DB11. How it copes with real roads, whether its new aero- dominated design stands the test of time as successfully as the DB9 and, of course, the earlier iconic cars, and if the instant gratification of the torque-rich engine rewards long-term as much as the searing top-end delivery of the characterful old 6.0-litre V12. However, here and now, parked side-by-side with all the DBs that went before, it already feels part of the family.

How so? Well, that’s a complex question and it’s hard to quantify. Perhaps it’s that, despite the DB11’s new technology and the obvious Mercedes-Benz influence in the control systems, it feels unlike anything else, here’s something old school and captivating about the DB11. The front-engined, rear-drive layout and the intuitive balance that creates. The elegant proportions that seem exotic and yet reserved at the same time. The sheer endlessness of the power delivery and the deep, howling noise. It’s a car that you just want to use.

Within minutes of experiencing it you conjure up fantastical images of sweeping down to the south of France. Peeling off the autoroutes and pouring along the Route Napoleon, V12 engine reverberating off bleached-out rockfaces and friendly locals throwing freshly made croissants and knickers at you wherever you stop. You sense life with a DB11 would be a life worth living, just as it would be if you had a DB5 tucked up in your favourite barn or raced a DB2/4 at Le Mans Classic. It has that DB magic. It’s little wonder that, despite the rumours and buzz about who will be the next James Bond, there’s no suchuncertainty about his next car. I’d suggest he goes for Lightning Silver. It really does look rather good.

THANKS TO Aston Martin and Aston Martin Works, www.astonmartinworks.com, all the owners, and Millbrook Proving Ground, www.millbrook.co.uk.

TECHNICAL DATA 2016 Aston Martin DB11

Engine 5204cc twin-turbo V12, DOHC per bank, 48-valve, electronic fuel injection and engine management

Power 600bhp @ 6500rpm

Torque 516lb ft @ 1500rpm

Transmission Eight-speed paddleshift automatic transaxle, rear-wheel drive

Steering Electric rack-and-pinion

Suspension Front: double wishbones, coil springs, electronically adjustable telescopic dampers, antiroll bar. Rear: multi-link, coil springs, electronically adjustable telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar

Brakes Grooved, vented discs, ABS

Weight 1770kg

Performance Top speed 200mph. 0-62mph 3.9sec

DB10: SPECIAL ORDER FOR MR BOND

This is the Aston Martin that money can’t buy – well, unless you were the individual who paid £2,4 million at a charity auction early this year to secure the one-and-only Aston-Martin DB10 that has been released into private hands, And even that kind of cash didn’t purchase a road-legal vehicle; it’s not Type Approved, and the contract of sale forbade the winning bidder from attempting to make it usable on public roads, Nevertheless, someone clearly felt the price was worth paying for the privilege of owning one of the ten cars specifically built for the Bond movie Spectre, perhaps because it had plenty of on-screen time in a thrilling pursuit with a Jaguar C-X75, Naturally,

Despite the DB10’s dramatic looks – which prefigured some of the Aston Martin DB11 design cues – the underpinnings were less radical, consisting of a stretched and widened V8 Vantage platform, (The V8 was chosen rather than the V12 to allow more room for stunt car technical wizardry,) Octane contributor Richard Meaden drove this car for our sister magazine Vantage and reported that ‘it does feel far more together than you’d ever imagine for a moving film prop’. Oh, and it also features the ultimate in-car accessory: an ejector-seat switch on top of the gearknob. Mark Dixon