It is on our third charge of the bend that I discover the surprise this new Ferrari-delivers. That’s when I realise that the 456 can be thrown sideways almost as easily as a shopping trolley, and that you can get away with it. There are no great skills required: the simple truth is that this Ferrari grand tourer is as happy to play the go-kart as a Mazda MX-5. And it’s so controlled, and controllable, with it.

The feat is all the more surprising given the Ferrari’s size. It’s long and wide – and, in case you’d forgotten, expensive, too, especially when it happens to be one of the factory’s few development hacks. But on that third run, I just can’t resist it. We’re plotting celluloid trajectories for cameraman Andrew, and as the tree-lined right-hander looms again I know I just have to stab that throttle to see what will happen. Foolhardy, perhaps, but this car has displayed such urbane manners that you can’t really believe it will turn grizzly. And so it proves. About a third of the way through the turn, a smooth-surfaced, gravel-rimmed second-gear bend, I tread the accelerator hard, hands ready to swivel the wheel should the rear tyres slide free. Sure enough they do, the outer cover tracing a parabola of spent rubber as grip is defeated by grunt.

From the cool blue leather-lined world inside the 456, the drama is muted. A swift, momentary anti-clockwise swivel has the 456’s nose drawing away from the trees and back towards the road, and we’re on our way again, marvelling at the mastery of its chassis. Making the 456 slide is like watching a butler pole- vault with the same seamless elegance he disports when serving tea. It’s an unlikely and compelling circumstance, and one you want to see repeated.

There’s further surprise in the fact that this is a grand tourer, a trans-European charger whose mission is to speed its occupants effortlessly and elegantly to their expensive destinations. Its main purpose is not assaulting mountain passes – and yet it’s consummately able to play that role. Certainly more so than its predecessor, the Ferrari 412 / 400 / 365. Long gone, that car was built for people who wanted a Ferrari, but didn’t really want a sports car. Nevertheless, it was the ultimate businessman’s express.

According to Ingenere Franco Cimatti, who tests and refines Ferraris until they’re fit for the road, the 456 is more of a sporty grand tourer. Now, what was Ferrari’s last front-engined, V12 grand tourer of sporty demeanour? Yes, the famous Ferrari Daytona. And we’ve brought one along, or rather Mr Ian Fraser, late of this parish, has, having just driven his 1973 model from Norfolk to Maranello.

Now we aren’t dumb enough to think the Daytona might prove the better car, but it will give us a fix on where a quarter of a century’s worth of development has taken the front- engined Ferrari. And the answer sets us thinking about where the usable supercar might possibly head next. But more of that later.

It was a bright morning when we arrived at Maranello to collect the silver 456. Before setting off, we feasted on stories of its technical delicacies during a dissertation from Cimatti. He is particularly pleased with the brakes, for instance, which he claims withstood a regime of rigorous abuse rather well.

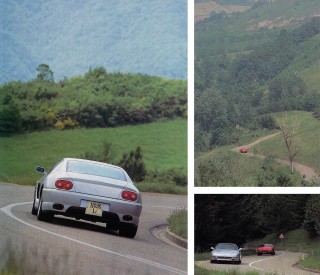

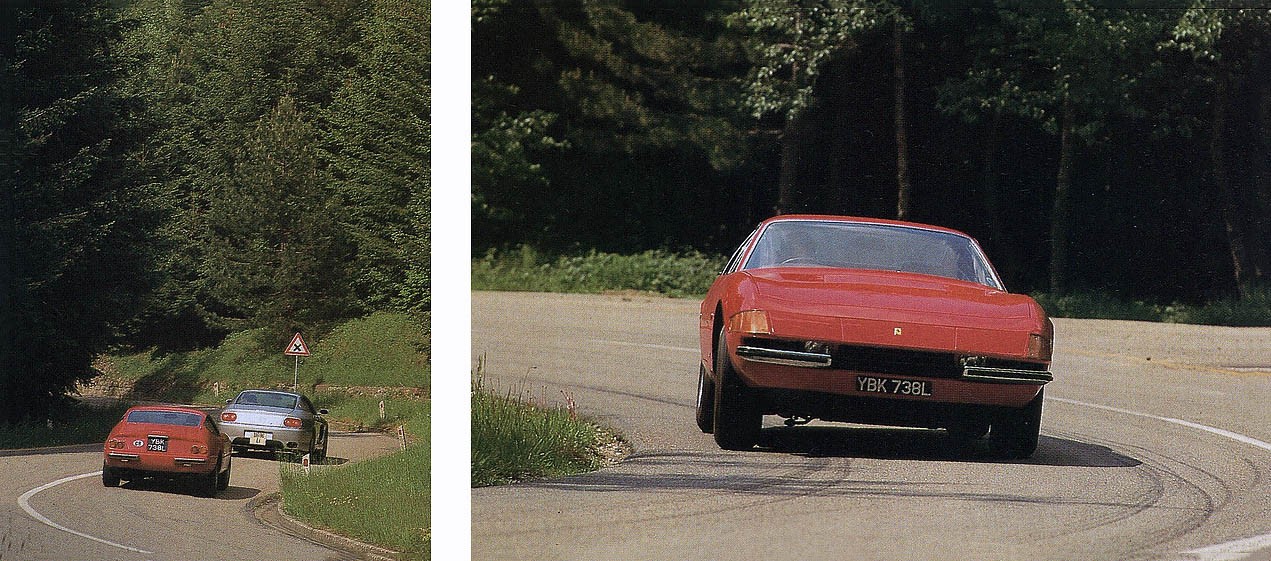

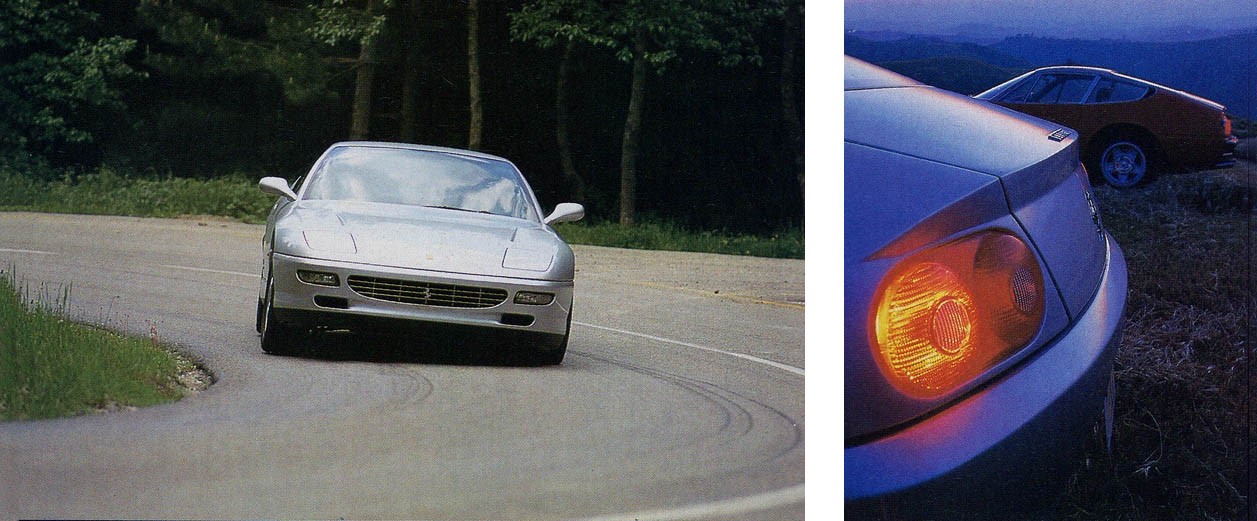

Rear end of 456GT echoes Daytona, notably rear lamps, boot lid and rear screen. From the front, car is let down by clumsy bumpers and flatness of bonnet and wings. Daytona looks at home in Italian countryside.

The treatment includes 15 flat-out laps of a variety of Italian race circuits, Mugello among them, and 10 laps of Fiorano, which Ferrari’s measurements reveal to be one of the most demanding circuits of all when it comes to shedding speed. The equipment on the receiving end includes discs taken from the 512 TR (though not cross-drilled), four piston calipers at each corner, ABS, and a hydraulically pumped booster.

Another of Cimatti’s techno-highlights is the electronic suspension. My heart always sinks when I see these two words juxtaposed, because it usually means the victim vehicle has damping characteristics to rival a kid’s bouncy castle. Cimatti alleviates the doubt, however, when he explains that it’s a development of the system used on the Mondial, for that one works quite well.

There are three manually selected settings ranging from soft to hard, dampers whose valving is adjusted by stepper motors (now in a mere 150 milliseconds, in contrast to the 500 needed by the Mondial’s dampers) and a battery of sensors harvesting for a potent computer that alters not only the damping range of the shockers, but also the damping curve, which influences their performance in ways more subtle than the average system. The sensors determine steering wheel angle, the straight-ahead position and the rate at which the rim is swivelled; there’s also a vertical acceleration sensor to detect movements that can induce motion sickness (so the suspension can heave gently without you doing the same) and a brake-line pressure sensor.

The self-levelling system that also features is a necessity, Cimatti says, in a car whose payload can alter significantly. When it is laden, four-up with luggage, the GT’s weight distribution settles at 49 percent front, 51 percent rear. One-up, the figures switch ends. Such even weight distribution is largely down to the Ferrari’s mechanical layout which, like the Daytona’s, has the gearbox mounted at the rear in unit with the differential. The suspension layout is equally classic, consisting of a quartet of coil- sprung double wishbones.

The steering gear is not traditional at all, other than that it’s rack and pinion. It’s a ZF Servotronic system, and features a rack whose tooth pitch alters (the steering quickens as it moves further off centre) and variable boost ratio. The steering isn’t especially quick 30 degrees either side of the straight-ahead, so that your 180mph sneeze doesn’t blast you to oblivion, but beyond this its rate increases by as much as a third. And the level of assistance diminishes in concert with your rising speed. On top of this, there’s a positive-centre-feel system to give more resistance about the straight-ahead, provided by a tiny torsion bar. This arrangement, you spotters should know, was pioneered on the Rover 800.

So the 456’s chassis wears plenty of technical dressing, and our test car, the silver machine, wears the scars of hard use, too: its nose gathered a rash of stone chips, Cimatti tells us, at the Nurburgring. Our guide also points to a number of sub-standard, pre-production items on the car: not least of these is the door sealing which, he says, will be noisy at speed. But as we leave, the expression on his face is one of confidence. He knows we are going to enjoy this car.

Jiggle and jerk that electric seat into position, alter the plane of the electric door mirrors, crank up the air-conditioning in the pre-cooked cabin, fire up, belt up and cup that big alloy ball of a gearlever knob, still cool to the palm. The V12 is there, a metallic satin chatter, loud enough to note, quiet enough to ignore. Cimatti apologises for the lacklustre exhaust note – ‘it’s the catalysts’ – and, as we depart to meet the Daytona, we can see what he means. Those twin pipes play flat.

We head for the Futa pass: a section of the Mille Miglia seems a good place to go with these Ferraris. Not much acclimatisation time is required – the 456 is an easy drive despite its apparent girth. The driving position is good, and easily refined via the versatile seat adjusters and trimmable steering column. The view ahead is clear, the clutch decently damped, the pedal weights pleasingly judged. The conventionally gated gearlever moves about more easily than other Ferraris’, too, though it still needs more effort than any Japanese box.

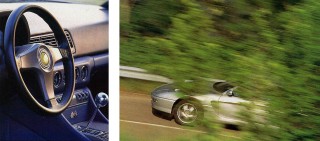

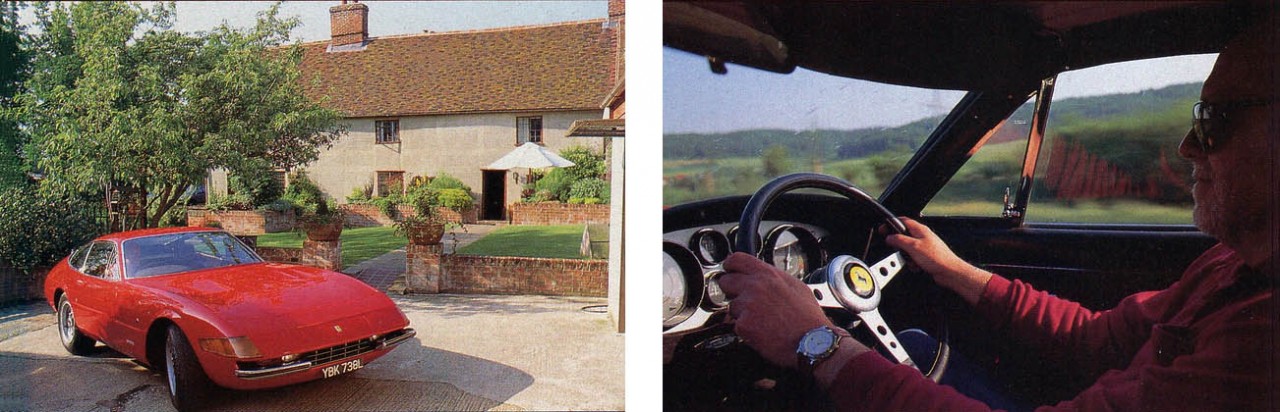

456GT cabin is plush, but let down by tacky detailing. Interior space better than it looks. Traditional Ferrari features such as chrome gearlever gate and pop-up headlamps are retained, of course.

The V12 behaves perfectly – as it should given that fuelling and firing are electronically regulated – the steering is never a bind and the brakes don’t concern except for feeling a little dead. But there are disappointments in this elegantly planned cabin, and one is the instrumentation: the major dials – tacho and speedo – are too small, and the minor gauges, spanning the centre console as if lifted from a ’60s GT car, prove a difficult, distant read.

Such minor troubles are soon subsumed to the pleasures of a tightly wound, climbing road that takes us towards the pass. In the windscreen are walls of green, in the mirrors flashing dashes of red. Massed foliage overhangs the road, and as we ascend I catch the Daytona in my peripheral vision, twisting, turning and rumbling. If that’s a sight to light up the senses, steering the 456 certainly turns up the heat – not from the effort, but from the thrill of it all. Our route is narrow and this car wide, but it has wieldiness on its side: only moderate efforts are needed to manipulate it, and it’s easily placed. Throw in supportive seats, roll- resistant suspension and a ride that rarely jolts, and you have a package that can be punted through tight turns at quite some pace.

By the time we reach the top, the Ferrari’s a little warm – it seems to run fairly high water temperatures, though the oil doesn’t heat up in the same way – but I feel quite cool, chilled by the air-conditioner’s wafts. A bite to eat, and we’re back on track, descending on tarmac sticky and aromatic from a recent stone dressing. This time I follow the Daytona, its twin exhausts occasionally spuming lazy black plumes, its dimly illuminating circular brake lights a clue to its age.

It really is a great looker, the Daytona. All bonnet and heft, and yet those finely drawn Fioravanti curves avoid a brazenly muscular look. Two seats and a V12 it may have, but there’s subtlety in its presence. Subtlety is demanded of you, the driver, too, as I shortly find out. At the bottom of the hill we swap cars, Fraser handing over the keys to his beloved as readily as if it were a Budget rentacar. Brave man.

Boy, they’re different, these two. It’s hot in the Daytona cockpit – there’s air-conditioning, but it’s none too effective – but the most obvious difference is in the angle of the steering column, which presents the leather-edged, alloy-spoked wheel in the same plane as a Mini’s. I feel as if I’m about to drive a low-slung bus. The seats are low, too, leaving the scuttle high and the whereabouts of the long bonnet anybody’s guess. After reeling in the static belt to suit (sorry, Ian), I give the Daytona half throttle, as instructed, twist the key and spin the 4.5-litre V12 into some sort of rhythm, the warm motor needing occasional gouts of fuel from the Weber six-pack to stay alive. First is on a rearward dogleg, goes in easily and, after a little stutter, the Daytona is off, to the accompaniment, it seems, of a dozen slightly worn sewing machines, for that is what the thresh of those valves, cams and chains resembles.

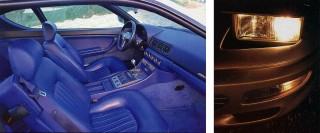

Daytona interior dated, has classy charm: bucket seats are excellent, and instruments better grouped in some ways than 456’s. Engine gives 352bhp from 4.4-litre V12, has lumpy response from six Weber carburettors.

I struggle for second, which is further across the gate than you’d expect, and reflect that I’m at the wheel of a legend. I’m also at the wheel of a car that is struggling to deal with the rolling folds of this rough old road, which pummels at our tyres with greater effect than it manages in the 456. This is not a light car, and when a wheel drops into a pot-hole you know it. So you try to steer around the deeper pits, and notice that the steering is grades heavier than in the 456 – unsurprising given that it is utterly unassisted.

The Daytona, you discover as confidence builds, has two direction-finding instruments: one big, circular and in front of you, the other small, rectangular, compressible and under your pumps. We leave our rough tarmac to stride the broader reaches of the road that takes us to the Futa and Raticosa passes and more stretching speeds. You need more technique to get the Daytona shifting quickly along roads like these, and it’s the old one of slow in, fast out, not least because we can’t see around many of the bends, and an old car like this simply hasn’t the same margin for error as the 456.

But the Daytona is no less intoxicating for that, not least because it makes a major call on you. And after a few bends you discover that plunging harder with that throttle alters the car’s agility. It’s almost as if it sheds weight, pounds of it, mid-bend. The Ferrari turns more keenly, feels more nimble, on the tips of its toes. The steering is lighter, too, but remember you’re on the edge here.

456 impressive performer, puts power down extremely well. Family feel to facias, but air conditioning on Daytona hopeless. 456’s engine superb: 442bhp and 405lb ft from 5.4 litres of 48-valve quad-cam injected V12.

Drive it below this state, and it feels quick but cumbersome and old. You need to shove hard on the brake pedal to shed mph, heave on the wheel to get the nose angled for attack, ready yourself for evasive action if the tail goes lighter than planned.

But there are some things the Daytona does better than the 456. It provides better all-round vision, for instance – the over-shoulder view is less restricted and the forward pillars more slender – and, more crucially, its steering delivers better feel. The column kicks sometimes, but mostly it transmits crisper, cleaner messages. The older car has better instrument grouping, too. The tacho and speedo are still too far apart, but at least all the minor dials are in the binnacle with them.

Still, you can always listen for trouble, and the V12 is not backward in coming forward with waves of noise. Its tappety chatter is counterpointed by a deep, loud and resonant bellow when you raise the revs, though you hardly need aural confirmation of its potency.

Pull through the Weber’s early gulping reluctance and the engine pulls clean and hard toward its late rush to the lofty 7700rpm limit. We don’t venture quite that far, for this is an old car, but gunning hard past 5000rpm tells us all we need to know – maximum wallop comes when the engine is thrashing at full stretch. That’s when the V12’s throttle response is at its keenest, when the mildest twitch of the accelerator alters your pace, because that’s where the cams are shaped to operate best.

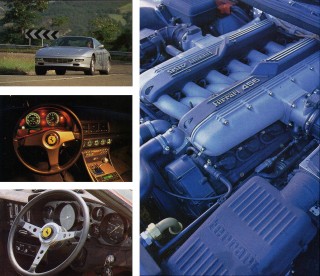

The Daytona isn’t slow on the uptake among the calmer reaches of the rev range, but it isn’t quite as eager as the 456. Modern injection gives the new car the edge, though there’s also the small matter of extra cubes. The 456 V12 displaces 5474cc, corrals 442 horses at 6250rpm and churns 405lb ft of twist action at 4500rpm. Its twin pairs of six cylinders sit 65 degrees apart (an odd figure arrived at mainly for packaging reasons, says Cimatti) and they’re crowned by twin-cam heads of 24 valves apiece. There’s no mechanical trickery in this engine – no variable valve timing or intake tube length – it’s just another straightforward Ferrari V12.

The Daytona motor, on the other hand, is of 4390cc, and delivers 352bhp at a more frenetic 7500rpm and 318lb ft of torque at 5500rpm. Despite being disadvantaged, the Daytona isn’t far behind the 456 when it comes to go.

The old car tops out at 173mph, having brushed 60mph in 5.8 seconds on the way; the new manages a memorable 194mph and 0-62mph in 5.6 seconds, according to the factory, though Italian journalists at Quattroruote have made 62mph in just 5.2sec. So against the watch there isn’t so much difference between these two.

Under foot, however, the story feels different, largely because the 456 is that much more willing to let you at its wares. It’s injection that does it, of course, allowing the V12 to breath evenly, no matter how low the revs. In the Daytona, tapping the throttle to prevent a stall at idle rapidly becomes ritual, as does the understanding that a lunge at the throttle doesn’t always produce an instant surge of power, because the Webers sometimes gag.

Still, that’s progress. And the advance amounts to more than serving up a well behaved respiratory system for the 456 has progressed on pretty much every front – as you’d expect. As a driver’s car, we’d place the 456 on at least the same plane as Ferrari’s 348 and 512 TR. It offers similar performance and, we suspect, similar grip and superior predictability – and predictability is what allows you to enjoy a car’s dynamics to the full. All of which has us wondering whether there’s a case for building, and billing, a front-engined supercar as the ultimate driver’s car.

Not that the 456 scores maximum points for its dynamics – its steering is too numb. But it’s damn impressive all the same. What isn’t so pleasing is the quality of some of the componentry, particularly inside. The toggle switches, an amusing retro echo from the ’60s, would be more convincing if they weren’t made of the cheap plastic from which ghetto blasters are moulded, and the same goes for the chromed plastic instrument bezels. Then there are the exterior door handles, which have none of the elegance and delicacy of the old 412’s. As Fraser says, there’s less to covet in this car than in Ferraris past, fewer of those pleasure-giving details that separate it from the horde.

Despite the car’s magnificent abilities, there’s something missing from the driving experience, too. Dated it may be, but the Daytona was a magnificent experience in its day. The 456, despite its splendid abilities, doesn’t quite provide that. So, Mr Cimatti, how about a stripped, lightweight 456 with heightened sensory telegraphing equipment, as a high- octane supplement to your svelte four- seat cruiser? It would be quite a car.

Both cars designed by Pininfarina: firm hasn’t lost its touch over past 25 years. Daytona handles well, but needs effort and concentration. 456GT, on the other hand, supremely chuckable, deft for such a big car.

Germany, I have pushed some extra air into the 215/70×15 XVR Michelins, but I am soon to find that my thinking has been wishful. Vast sections of the autobahn system are now subject to 130km/h speed limits; roadworks abound as the authorities try to patch up worn- out surfaces, which results in long queues and endless frustration. I end up wishing I’d left the tyres as they were, because the ride is very harsh by modern standards at the enforced low speeds and there seems little prospect of achieving the velocities for which the car was designed.

By Koblenz, 300 miles into our trip, the fuel gauge is suggesting that another dose of leaded super is needed. We fill up and do the sums. Much better than anticipated: 17.9mpg. For a 352bhp V12 with six double-choke carburettors, born before electronic engine-management systems were thought of, this figure is not at all bad.

Although we moan about the road conditions more or less throughout, the 620-mile run from Calais to the Holiday Inn in Munich takes about eight hours. We make only two stops, eating junk- food picked up while refuelling and drinking plenty of water, but what surprises us most of all is the comfort and support provided by the rather skimpy-looking seats. The hotel’s car park serves to remind me just what a rotten turning circle the Daytona has.

The specification claims that it’s a fraction less than 40ft, but it seems a lot more. At the end of our long drive, the high-geared recirculating ball set up feels even heavier than usual, too.

On Monday morning, we decide to wait until the Muncheners get themselves off to work before setting off. Ahead of us is an easy run down to Modena via Innsbruck, the Brenner Pass, Verona and Mantova. A couple of dabs on the throttle to get some fuel into the manifolds, a twist of the key, and the V12 rumbles into life once more. It has always been an easy cold-starter, this engine. When hot, it comes to life quickly enough as long as you remember to open the throttle about halfway as the starter cranks it over. I hate driving off on a completely cold engine, so I let the Ferrari tick over briskly for a few minutes to get the oil circulating. However, the gearbox takes up to 15 minutes of normal driving before second is freely available – a characteristic that’s common to plenty of Italian performance- car transmissions.

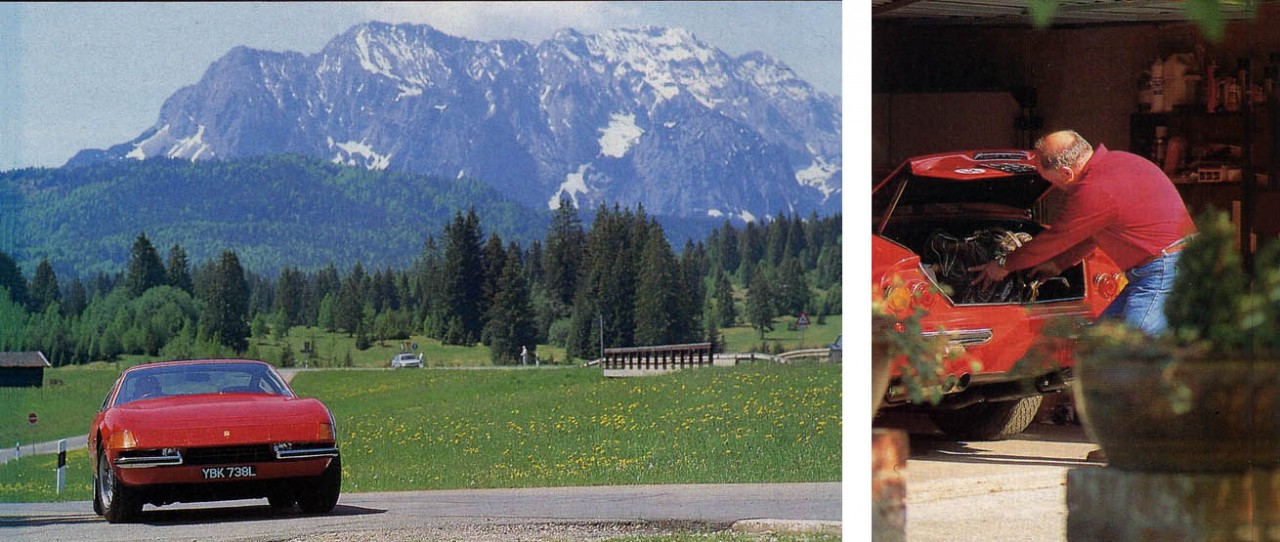

The roads that lead south from Munich are superb. After only a handful of miles, we are surrounded by dense forests backed by the jagged skyline of snow- covered Alps. The ordinary road that leads to Innsbruck is shorter and more spectacular than the autobahn alternative, although it’s ultimately slower, of course.

In Norfolk, just before start of the 1200-mile trek (top left). Fraser and Daytona calm at 120mph in Germany (top right). Spectacular Alpine scenery in Austria (above). Boot space limited for trans-European tour (right)

The autostrada down from the Brenner is one of the great civil engineering achievements of our time. But it takes a merciless pounding from heavy lorries, is too narrow, and surface deterioration seems to outstrip its owners’ ability to keep it in good repair. Each time I drive on it, it’s worse. And the W-section safety fencing appears to be rusting away. It’s a good test of the Daytona’s all-independent coil suspension, though. It has to work for its living and, although not silent in operation, is compliant and effective, managing to maintain good pitch control over the crests and hollows of the sagging concrete sections. There are endless speed limits and half-hearted roadworks which make the limits lamentably realistic. Still, you get enough time to admire some of the most stunning mountain scenery in Europe, the ruined fortresses and castles forming a reminder that the Italian/Austrian border was not always at the top of the Brenner. Indeed, the Italian Tyroleans are Austrian in just about everything except their currency.

It is here that I notice that the engine’s oil-temperature gauge (which hardly gets off the bottom stop in Britain) is – in this heat – enjoying a romp halfway up the scale. The oil pressure remains steady, however, as does the water temperature.

At Modena, I pick my way through the familar streets – and a one-way system: what next? – to the Via Emilia and the ever-welcoming, ever-efficient Real Fini Hotel. Ferraris don’t cause so much as a raised eyebrow at the Fini, since it is the main stopover for visitors to Maranello.

With the Daytona safely tucked up for the night, and a couple of spare hours in hand before our meeting with associate editor Bremner, art director Chappell, and photographer Andrew, we quaff a refreshing beer and take an early evening stroll down Via Emilia into the town centre. The heart of Modena is now a car-free zone, and all the better for it. But you still have to contend with trolley buses and teenagers on mopeds. Recession may have knocked the stuffing out of many cities, but Modena looks in good health.

On our return to the hotel, we’re confronted by a couple of nasty shocks. First, the Ristorante Fini – one of the world’s great eating establishments – is closed. A disaster of some magnitude, because I have been carefully nourishing my anticipation with the thought of eating there. Second, a shiny, new six-door Mercedes limousine draws up to the front door. It bears all the hallmarks of a replacement for the hotel’s ancient fin-tailed Mercedes-Benz, which was used primarily for transporting patrons from the hotel to the restaurant.

To cure the culinary crisis caused by the Fini’s locked doors – four famished people are demanding masticatory action – we decide to steer clear of Arnaldo’s, some nine miles out of town, on the grounds that a veritable legion of Ferrari devotees is heading that way.

The Modenese understand about eating and it’s not long before the manager of our hotel discovers that Lauro’s (which is supposed to be closed on Mondays) is in fact open, but not advertising the fact. Grateful for this knowledge, we dine there on Emilian specialities washed down with the sort of Lambrusco that your local supermarket does not sell. Lauro’s, it transpires, is an unofficial Ferrari branch office, frequented by drivers, engineers and so on – as confirmed by the signed photographs that decorate the place.

On Tuesday, in company with the 456, we attack the Apennines. Traditionally, Italian supercars were blooded in the Apennines, over the Futa and Ratacosa Passes particularly ;which were once on the main route south, and also made up some of the most challenging sections of the Mille Miglia proper). Prototype Daytonas were tested here too, of course.

These mountains are hard work in any car, and the Daytona makes no concessions. It’s a big car, with a long (mostly invisible) nose, very heavy steering, and brakes that require both forethought and muscle power. Skilful use of the throttle plays a big part in getting the best from the Daytona, since it is the handling – rather than the roadholding – that gets it around the corners. Old Ferraris have little in common with the likes of the 456; after all, we are talking about 25 years of development. In addition, customers’ needs have changed. The supercar buyer of today requires grip; he is less enamoured of opposite-lock excitement.

A hugely entertaining day spent thrashing the car in the mountains hammers the consumption down to 16.5mpg, but gives the old V12 a thorough clean out. Both engine and transmission are tireless performers.

The 85mph second gear cheerfully hauls the monster out of uphill hairpins.

A couple of times I have to resort to first – good for 55mph – but mostly the upper ratios do the job fine. The change mechanism is very positive, especially considering that the gearbox is married to the differential. Neutral is wide, with the spring bias favouring second and third, first being outboard.

After driving the 456, I reflect upon the rawness of my Daytona, and admire the newcomer even more. Nonetheless, I think I could only be happy owning both. One could not replace the other. The Daytona is sheer driving enjoyment at its basic best, whereas the 456 offers subtler pleasures.

On our return trip, we find that Munich is very short of hotel accommodation (owing to a big football match), so we head out to a little country inn and stay there for next to no money, leaving the car in an open parking area. No harm comes to it. So disillusioned are we with the autobahn system that we trace our way across to Saarbrucken, so that we can get onto the French autoroutes as soon as possible. They may not be cheap, but they work very well – as long as you don’t feel compelled to go seriously fast.

The route across France via Metz to Reims then direct to Calais is relatively empty of traffic, so we are able to maintain a steady average without offending policemen. We are back on British soil 12 hours after leaving our hotel in rural Bavaria.

Door to door, we covered 2507 miles in four countries and nothing broke or dropped off. On a rough road leading away from the Apennines, the pop-up headlamps began inexplicably to sag. But that was all. They recovered, and have not misbehaved since, although at the time it seemed like the prelude to a major electrical crisis. The engine needed about two litres of oil added to its dry-sump lubrication tank (the level of which, as a matter of interest, can only be checked accurately when the engine is running).

It was a good trip.

Daytona and Ferrari 456GT at rest beside Futa pass, while Frasers senior and junior, Tim Andrew and Richard Bremner take sustenance / 1993