JAG’S BEST SALOON How John Coombs’ hot Mk2 was brought back from the dead. The former Coombs apprentice who built the last Mk2. Noddy’s last Jaguar Mk2 An ex-Coombs worker finished off his former boss’ final hot saloon.

Most enthusiasts have a close bond with a make that sparks their passion, be it a first car or their parents’ transport of choice. For Richard Grimmond, it’s Jaguars – a lifelong affair that began with a first job at one of the marque’s most famous dealers.

Grimmond started his apprenticeship at Coombs Garage in 1961 when he was just 16 years old. “I was mad about Jaguars and knew early on about the famous garage in Guildford,” Grimmond recalls. “My dad ran a chicken farm and wasn’t mechanically minded, so my mum used to get me to do all the jobs and bought me tools. I used to run our grey ‘Fergie’ tractor on the local tracks and Dad eventually taught me to drive in an Austin Seven Ruby that had a wicked clutch. He wasn’t really interested in cars but did take me to Goodwood from ’58. Mike Hawthorn was a hero and I vividly remember being in the playground when we heard the news of his big crash just up the road on the A3.”

When Grimmond joined Coombs, he still hadn’t passed his test: “I cycled at first from dad’s farm in Wood Street to Portsmouth Road. It was a really good apprenticeship. All the guys were helpful and friendly, which is probably why we’ve kept in touch. The garage loaned me the ‘works’ Ford 100E van for my test, but I don’t think the examiner was very impressed when I turned up at the centre. He looked at the silver signwriting on the side and drew a deep breath. Worse still, he opened the passenger door only to discover that he had to sit on a box but at least I’d brought a cushion. Unsurprisingly, he failed me.”

During his five years at Coombs, Grimmond feels lucky to have witnessed a golden era of Jaguar history: “It was an impressive garage with over 50 people employed. We did everything in-house, including bodywork and trimming. From 19, I was on my own doing mostly clutches though I’d also help out with the race team. The competition side was in a barn at the back, where talented guys such as Roland Law worked. He later joined Jackie Stewart. We never got paid for weekends but were happy to go to races to help. Graham Hill was a nice bloke. He was always amusing, though you soon learnt to leave him in peace before races. He used a Pearlescent Grey Mk2 Coombs 3.8 that we serviced.”

Grimmond was directly involved with building two special Mk2s with all of the upgrades. “Most of the buyers were rich stockbrokers,” he says. “The younger owners were good at writing them off. We had some famous customers and I remember Tony Hubbard visiting the garage.”

No one is definite about the actual number of Coombs Mk2s – there were never any records – although experts including specialist Ken Bell, another former apprentice, reckon about 34. Says Grimmond: “The boss insisted we take a new car from the showroom, but I recall modifying one second-hand car with a blown engine.

Coombs also stipulated that new engines were built from scratch. The head would go away to Brabham or Barwell for machining, while upgrades included 9:1 pistons, balanced crank, lightened flywheel and 2in carburettors. We didn’t have a dyno, so there were no figures. Testing and running in was done on the road.” Other mods included enlarged rear wheelarches, Koni dampers, a high-ratio Mk1 steering box and a straight-through exhaust with 2in tailpipes: “We sometimes stiffened the suspension and fitted an anti-roll bar. As well as conversions to wires, we’d also fit E-type steering wheels. The pre-’62 ones were thicker and stronger. We used to change loads because they would split when drivers pushed on the rim to get in and out of the car.”

Coombs Mk2s were the fastest saloons on the road in the early ’60s, and most sports cars would have little chance catching an experienced driver in a tuned Jag: “There was no speed limit and we had a test route down the Portsmouth Road and out to Compton village where we’d turn around and roar back. We’d get up to 100mph on the Compton straight. I once saw 120 where there’s a 40mph limit now. Sometimes two cars would be out on test and you’d hang back for a friend so you could have a bit of a race. On those Dunlop RS5 crossplies you could really hang the tail out on corners, but you can’t do it with radials. The police used to turn a blind eye, but got annoyed when our high-speed runs messed up their early radar guns that were calibrated to only 70. We’d occasionally take new Mk2s home to save time for a delivery to London. Also, John Coombs didn’t like driving at night so we’d often have to take him up to London to meet girlfriends.”

The arrival of the first E-type was a never-to-be- forgotten moment: “It was April 1961 and I was one of the first to arrive, at 7:30am. The car had been collected the night before and was still outside. It was Pearl Grey with blue leather and looked fantastic. We later did some of the development on the first E-types and there was always a tremendous rivalry with Tommy Sopwith.”

Grimmond has owned and rebuilt many Jags since his time at Coombs, but his first car was an Austin Seven Cambridge special: “As soon as I started driving it, the engine developed a knock. I took it out one winter and began rebuilding it in the chicken shed. Mum felt sorry for me working in the cold and allowed me to bring the engine into the house. We laid out some newspaper on the kitchen table and, although she couldn’t drive, she was fascinated by the job and helped.”

Grimmond bought his first Mk2 in 1966: “It came into Coombs with a broken engine. It had been run without oil and needed a new crank and bearings. My uncle had left me some money. It was light blue and cost £350. We towed it home through Guildford one Saturday morning with the tractor and John went potty when he heard. The engine was rebuilt at the farm, and it went really well. I remember roaring home one night and ripping the exhaust off over a bump. I kept it for six months then swapped it for an Alpine plus £500. I’ve tried to trace it but it’s long gone.”

Grimmond’s second Mk2 was a fire-damaged car that he bought at auction in the ’80s: “It had caught alight at the sale, which put everyone off. I ended up paying £3000 because I could see it was a lovely car. I cleaned it and detailed the engine bay, redid the wiring and resprayed the bonnet. After a year, I sold it on for £9000 to fund an XK150 but I soon missed it.”

Grimmond kept in contact with Coombs long after he left to start his own business in ’66: “He used to park his car outside my garage when he went to the dentist in Guildford, and we’d always chat. He asked my views about projects, including an E-type that he was modifying. He’d set his mind on lowering the engine and getting rid of the power bulge, which looked strange to me.”

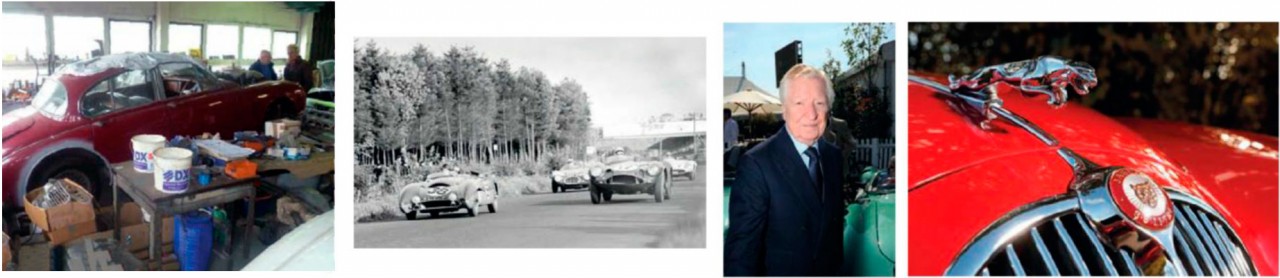

After Coombs died in August 2013, his last cars were sold, but unfinished projects including a Mk2 were slow to go. Grimmond had long set his mind on another one, and liked the idea of taking on his old boss’ project: “Coombs had bought it in 2003. It was a 1962 3.8 with overdrive and the bigger carbs. His guys had started the modifications, including the rear arches. The engine was out but they’d fitted a Mk1 steering box. It was first owned by a doctor and registered 6240 UR. The mileage showed 37,000 but was probably more, though nothing was very worn. The original interior was good, which I liked.”

The first challenge was to sort the bodywork: “It was a darker Inspector Morse-style tone, so that had to change. There was also a fair amount of rust, including the front valance, boot and sills. My son Michael was a great help, and we decided to strip it back to bare metal. The biggest challenge was the thick old underseal. For the first time I used a rotisserie frame, and for weeks we just chipped away. We filled several large dustbins with underseal until they were so heavy we couldn’t pick them up. Getting the doors to fit is always a challenge. Even at the factory they used lots of shims, and one of the first jobs at Coombs was to refit them properly at the initial service.

People talk about louvred bonnets but that’s a myth. They were used on the racers, but it would be a mistake for the road because it takes all the strength out of the bonnet. We also kept some of the wiring in place, particularly up the A-posts. The new loom, supplied by Autosparks, was brilliant – an exact copy of the original design.”

Grimmond dispatched the stripped body to his old friend George King at Thames Valley Repairs in Maidenhead: “We went for a waterbased, two-pack Carmen Red, but with a matting agent added. I didn’t want it to look like a boiled sweet. All the suspension was powder-coated. While the body was being done – it was away for a year – the chrome went to Colonnade in Wembley. They did everything including the window frames and the bill was £3000.”

Grimmond, meanwhile, rebuilt the engine with special attention to gas flow: “The secret is a smooth manifold face with no step.”

Where possible, he prefers to preserve patina – particularly interiors: “I just cleaned up the dash and set to with wax polish. It’s not concours but has character. The final touch was a period Motorola radio. All the glass is original, and Coombs never added transfers or badges. When I worked at Portsmouth Road, I chatted up the desk girls for a keyring and it’s now used on this Mk2 after years in my cabinet. The mascot is also a souvenir from my apprenticeship days.”

Once the shell was back, the refit began in earnest with help from Michael, now a respected E-type restorer. Tweaks included a straightthrough exhaust made by Mk2 guru Ken Bell and copied from the Coombs design: “I’m an originality freak but I also enjoy driving my cars, so upgraded parts are sensible although most can be undone. I do like stopping, so I’ve fitted four-pot calipers. The dampers are standard to maintain the ride but it has a stiffer anti-roll bar. It came with new chrome wires, which are a bit bling. In period, the cars mostly had painted wheels, often matching the body. The rebuilt back axle was the only thing that failed, after a bearing collapsed, but Hardy Engineering soon turned it around.”

A regular at the Goodwood Revival, Grimmond was determined to get the Mk2 finished for the 2016 event, where the family had a great early-morning run and parked on the Lavant banking: “It’s always a little emotional taking it out on the old roads where we tested the cars back in the ’60s. And, of course, I had to take it to our Coombs Garage Reunion in Godalming.”

The lunch with old workmates is always a source of great stories. “They were very happy times,” recalls Grimmond, “and, although John could be tricky, he was a generous character. He lived above the garage and always knew what was going on, but we had some laughs.” Pranks included welded-up lockers and screwing shoes to the workbench, but other tricks were more drastic: “One afternoon we filled a skip with acetylene gas and dropped in a match. The blast lifted it over a foot off the ground.” The bolder mechanics would occasionally target the boss, who would generally see the light side: “One afternoon we sneaked out to his new S-type, and pulled the handbrake on as tight as it would go. You can imagine how we laughed as he struggled to release it before charging back and demanding someone get it fixed. He never knew it was us.”

Other fun moments happened when the boss was out, including seeing how many people could be squeezed into a Mk10: “We got 22 inside but ran out of volunteers.” Unsurprisingly, he has a soft spot for the model and recently acquired a low-mileage unrestored example: “My wife isn’t very happy because she lost her potting shed so that we could store it at home. It’s totally original and they are getting rare. I’ve enjoyed getting it back on the road, and adore driving it.”

With three Jaguars, including his treasured XK150 roadster, an Austin Seven and an MG TA, Grimmond has a classic for any occasion: “I’ve always loved the shape of the AC Aceca, which is on my dream list. I’d also like to build another house.” Now beginning his seventh decade, I wouldn’t be surprised if this industrious enthusiast achieves both goals.

‘IT’S ALWAYS A LITTLE EMOTIONAL TAKING IT OUT ON ROADS WHERE WE TESTED IN THE ’60s’

Dash untouched apart from a good polish; period Motorola was the perfect finishing touch; mascot a keepsake from Grimmond’s time as an apprentice. Grimmond went for a fine compromise with the setup: standard dampers for a supple ride but with a thicker front anti-roll bar so that there’s less lean. When Grimmond (below) bought the Jag, it was a darker hue (see previous spread), so he resprayed it in the correct Carmen Red. Bottom: rebuilt gauges. Clockwise: rebuilt 3.8 XK sports twin 2in SUs, as per usual Coombs spec; prized keyring that Grimmond scrounged after chatting up the ladies in the office.

‘MUM FELT SORRY FOR ME BEING IN THE COLD AND LET ME BRING THE ENGINE IN THE KITCHEN’

Work in progress

From top: stripped to bare metal on rotisserie in home garage; loom was replaced with an exact copy; prepped bodyshell; back resprayed; rebuilt bottom end; suspension parts were powder-coated.

John Coombs

Born in 1922, Coombs was the son of a wheelwright and coachbuilder. He was indoctrinated with cars on trips to Brooklands. During the 1930s, his father built up a garage firm in Guildford that John took over in ’47. He began motor racing with a Cooper-Rover in ’50. Success with 500s earnt him a Connaught works drive, with single-seaters and then ALSR sports cars.

By 1955, Coombs had hung up his helmet to focus on work and, via the expanding dealership he built up close – if at times strained – links with Jaguar management. Clever marketing included a famous series of registration numbers such as BUY 1, OWN 1, TRY 1, and BUY 1 2. When friend Mike Hawthorn had his fatal smash on the A3, Coombs was one of the first on the scene, and related the tragic news to Lofty England.

Coombs remained closely involved with motor sport via his team, and the Mk2 battles with Tommy Sopwith of Equipe Endeavour became a highlight of British tintop events. When Colin Chapman phoned for a test drive of the new Mk2, Coombs immediately entered him for a race at Silverstone where he beat Jack Sears. When the shells for the racing Mk2s were delivered to Coombs’ workshop, all the lead was taken out before the seams were welded for stiffening.

To get the stripped cars back to the legal weight, lead blocks were mounted low on the floor. Always determined to get the first new model, Coombs would immediately drive around London to show it off at clubs and popular pubs. His star drivers included Graham Hill and Roy Salvadori, who kept the bodyshop busy with his regular nudges. After saloons and GTs, the team’s focus became Formula 2 through to the early ’70s.

Brabham, McLaren, Stewart, Courage and Cevert all drove for the Guildford outfit. Coombs also commissioned a high-speed launch with twin 3.8 XK motors. Built by AE Freezer, Cheetah featured an aluminium hull and took the rivalry with Sopwith to ocean racing. It was from his interest in boats and wearing a natty bobblehat that Coombs was nicknamed ‘Noddy’. Frustrated by BL in the ’80s, Coombs switched to BMW and sold the business to retire in Monte- Carlo. In later years, he built a fine collection that he often drove on international events, or entered top drivers to race. A fixture at the Goodwood Revival (above), Coombs died in 2013, aged 91.

Last race with his Lotus MkVIII in the 1955 Dundrod TT.