style=”light” size=”5″]In 1962 Harley Pederick, owner of Western Australian agricultural business Pederick Engineering, fancied a quick way of getting from rural Wagin to urban Perth. There were three clear choices for a man with a love of breakneck speed – an Aston Martin DB4, the new Jaguar E-type, or an aeroplane.

‘The business did well that year,’ recalls Pederick. ‘I looked at buying an Aston Martin but it was twice the price of an E-type and not much better. The Jaguar arrived at Fremantle Wharf without fuel or a battery, so Stan Starcevich and I decided to head down to the port and collect it ourselves. The car was in a goods shed with waterside workers around it. We began to push it, and the workers walked away. That was my first introduction to trade unionism!’

Harley Pederick buys it new in 1962 for AU£3000 Pederick and his colleague Starcevich were wellknown on the local dirt-track speedway scene, but the E-type made them competitive in faster events like the Albany Around-The-Houses race. ‘We took our Holden but it blew up in practice so we entered the E-type instead,’ says Pederick. ‘Its brake linings were worn, but the local dentist let us use the ones on his Mark X. We raced the E-type all day then put them back.’

‘The car always had poor brakes. The local experts couldn’t prevent brake fade, so we wrote to some UK specialists. They said that the brakes were the same as a D-type’s and we should just cut holes in the car and channel air through to them.’ Despite the braking issues, it was a successful year for the E-type, as Pederick and Starcevich won the Western Australian (WA) Sporting Car Club’s GT Championship, including the Byford Hillclimb and Albany Tourist Trophy.

‘We decided the 1964 Caversham Six Hour was to be the last time the E-type and I raced. I wasn’t well and we didn’t want to start chopping up the car, but we knew we had a good chance. Starcevich and I shared the drive. The brakes still faded. We’d be going down the main straight and as we approached the Coca-Cola curve we’d have to throw the car sideways to wash some speed of. We went down the run-of roads so often it was embarrassing. We were way out in front but Ted Lisle’s Mini Cooper S almost caught me.’

Stan Starcevich buys it in 1965 for AU$3200 Starcevich bought the car from Pederick a year after the Caversham win. ‘I’d known that car from the start, ever since we walked into Brookings Jaguar in Perth together looking like a couple of scrufs,’ he recalls. ‘The salesman’s attitude changed when Harley presented him with an AU£3000 cheque!

‘By the time I bought if of Harley it had sat around for a bit, so I gave him AU$3200 – about half its original value, as we’d just switched from pounds to dollars. It had a problem with its engine bearings – it went back to Brookings a lot early on. I took the engine out, had the crankshaft balanced, and had no problems after that. I had experience with Jaguar XK engines because I’d put a MkVII engine in a Holden to build a road/race car, and before the E-type I’d owned a 1959 MkI.’

‘I wanted to improve the braking and handling so I went to Can-Am racer Frank Matich in New South Wales. He was the Australian dealer for Firestone tyres, so I bought a set from him designed for road-racing. They transformed the handling compared to the Dunlop SPs, which wore out fast at high speeds. The Firestones were still crossplies; radials didn’t arrive until 1966. At the 1965 Australian GP I quizzed fellow E-type owner Bruce McLaren about the brakes. He said, “There’s nothing you can do – you’ve just got to accept that it’s a lethal weapon!” We’d change the pads, but we knew it was really a cooling problem.

‘Back then there was no speed limit in the outback. I saw 160mph on the speedometer at 6000rpm when Harley was driving one night. We used to run it on 115-octane aviation fuel – with its 9:1 compression ratio it wouldn’t run on pump fuel. We used to have four-gallon barrels of avgas delivered to our houses – it was cheaper too because it wasn’t taxed! I had the car for four years, and made AU$400 on it when I sold it to magistrate’s clerk and Mini racer Phil Davenport.’

Phil Davenport pays AU$3600 in 1969 Davenport didn’t do much with the car, repainting it in a shade of deep metallic blue and fitting Silver Streak tyres, although he did make history racing it (with bonnet removed) once at the inaugural drag meeting at Ravenswood Raceway in 1969, posting a 15.1-second quarter-mile time.

Davenport only kept the car for a year, selling it to two brothers from Geraldton, a port town north of Perth, in 1970. For two years the E-type became a regular sight in the car parks of Perth speedway tracks on Friday nights, because the brothers would make their weekly 300-mile round trip to watch – among others – Stan Starcevich racing Holdens and Fords. It’s entirely possible they had no idea they owned his old E-type. Carrington Car Sales then sold it to Stan Willner, who commuted to his restaurant in the Fremantle Post Oice arcade until a collision wrecked the bonnet. In 1976 Willner traded it for another E-type at Roadbend Jaguar in Welshpool, WA.

‘My father, Jim Percival, recalls taking the E-type out for a road test without its bonnet,’ says Graham Percival, current managing director of Roadbend. Allen Shephard buys it in 1977 After a year sitting in Percival’s showroom, the E-type was sold to Allen Shephard. ‘It had been driven into the back of a truck and was pretty sad-looking,’ Shephard recalls, ‘but I remembered seeing it for the first time when Pederick owned it. He’d driven it across a farm paddock at an event where his company was demonstrating a tree stump removal machine.

‘It took me two years to ix, then I starting racing it,’ Shephard continues. But it didn’t take long before Shephard ran into the E-type’s age-old foible. ‘The biggest problem was that I could never stop it! Back then if I couldn’t hit 100mph on the way to work I’d be disappointed. When braking from 100, it’d be OK until about 40 then you’d have to find a footpath or a side street to slow it down! I found that Jaguar and Chevrolet used the same front wheel bearings, so I fitted Corvette mag wheels and brakes.

‘In the Eighties we mainly did road-rallies in it, including the Targa Tasmania. My son, Phil, has been involved with this car since he was 12, and was navigating on the Targa when we hit a tree. The trunk got as far back as the first carburettor, and that’s the first time it got a new bonnet – I had a secondhand one at home. Before then we’d just kick the old one back into shape. They’re tough cars. The problem was that Jaguar only formed the bonnets’ back edges when fitting them at the factory, so replacements never it.

‘In 1996 we took the E-type on the Panama-Alaska, devised by Nick Britten who did the London-Sydney and London-Cape Town rallies. It covered 25 days, 15,000 kilometres and all sorts of closed road stages. And some of those ‘closed’ roads had horses and carts on them! The rally incorporated the Baja sand dunes.

Others circumnavigated the desert to avoid that section, but we went straight into it. Of the 28 cars that entered the desert, only 12 cars exited, including us despite me throwing the E-type into sand dunes in third. The only problem we had was the alternator failing in Honduras. Running 30th, we had to stop to ix it, but the rally curfew meant we spent the night in the car and didn’t book in at the end of the day, dropping us down the order. We still finished 38th.’

In 2005 a chance encounter led to Allen setting an extraordinary goal for the E-type – becoming the world’s fastest. ‘I was racing in Victoria and called into Lake Gairdner on the way back to check out the salt-flat racing. The E-type looked so out of place there.

People said it needed a V8, had no chance of beating the Corvettes and wouldn’t even need a 150mph braking parachute. I wanted to prove them wrong.

‘We needed more weight for traction, but looking for extra horsepower is difficult too – unlike circuit racing you’re flat-out all the time,’ Shephard explains. ‘We relocated the fuel tank to the nose so the fuel lowed into the engine more easily. Surprisingly there was no overheating problem as a result – methanol is a cold fuel! It needed dragster front tyres rated for 175mph. Amazingly the Pirelli tyres for the Jaguar XJS, which it the rear wheels, are already certified to 185mph.

‘The compression ratio needed increasing to 12:1 for the methanol to burn, but we had to keep the original conrods and cylinder block to be eligible for the production class. All we needed to drive it on the road was to change the front wheels and remove the wind deflectors. That said, the fuel injection system isn’t good in traffic, and the police don’t like you driving on the road with a full cage. In order to approve it for salt racing the track officials time you getting out of the car, as the ire trucks take a while to get to you.’

The serious work began in February 2007. Allen recalculated the differential ratios, with 2.88 giving 175mph at 6500rpm. A test run at the century-old Lake Perkolilli track vindicated Allen’s modifications. Allen and Phil then started working towards their Dry Lakes Racers Australia (DLRA) speed licences ahead of the organisation’s 2008 Speed Week Tour. Bad weather intervened, so the first attempt had to wait until 2009.

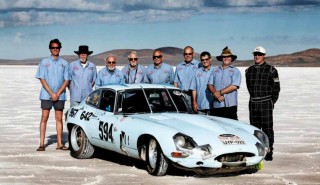

Incredibly Allen, Phil and the E-type claimed their 149mph licences on their first day at Lake Gairdner that year after a successful 140mph run. The following day, with Phil at the wheel, the E-type was clocked at 146.603mph, qualifying them for their 150mph licences. ‘We told anyone that would listen that we would be back next year with a parachute,’ says Phil.

For 2010, Allen overhauled the car, including a new engine based around an XK cylinder block that he’d originally fitted to a speedway racer but had sat under a workbench for 40 years. ‘I knew it would come in handy sometime,’ he quips. Rebuilt with high-lift camshafts and high-compression pistons, an electric water pump, a straight-through exhaust and a mechanical fuel-injection system, it was fitted into a car now sporting a 3.31 differential ratio. Seven days later ‘Team Shep’ arrived at Lake Gairdner again. On Allen’s first run he managed 146.032mph, but diagnosed a misfire caused by a loose fuel line upon returning to the startline. Hose reattached, Phil climbed in and managed a 161.870mph run. ‘It was a new production E-type/GT-class Australian land speed record, which made the grins even wider!’ says Phil.

The following two years’ events were cancelled because of bad weather, although Allen, Phil and their team continued to modify the car. In March 2015 Phil Shephard took the E-type to 170.086mph, a new world record for a production E-type. ‘We are the undisputed kings of our own salt domain,’ he beams.

However, the Shephards’ quest to push the E-type as hard as possible had come to an end. ‘On the day of the 170mph record, we saw another father-and-son team involved in a fatal accident,’ said Allen. ‘I decided to quit while I was ahead. The E-type hasn’t retired, though. It does historic races now including the Phillip Island Classic. However, it doesn’t usually go that far – all the best circuits are on the other side of Australia!’

Thanks to: Graeme Cocks. The book The World’s Fastest E-Type Jaguar: The Quest for the Record is available through motoringpast.com.au

“It was a new E-type land speed world record – we were kings of our own salt domain”

“If I couldn’t hit 100mph on my way to work I’d be disappointed”

The Jag in the early Sixties alongside another member of Pederick’s fast fleet. Allen Shephard a speed record at Lake Gairdner in 2010. Forming part of an electric grid at the 1964 Caversham Six Hour race. Pederick overcame chronic brake-fade to take the win at Caversham in 1964 – and he still hast the trophy to prove it. After buying the E-type in 1969, Phil Davenport painted it blue. Quarter-mile sprints at the newly opened Ravenswood Raceway in 1969 with a magistrate’s clerk at the wheel. Allen Shephard negotiating 15,000km – and the occasional cactus – on the Panama-Alaska in 1996. A tyre change on Australia’s Nullarbor Plain sometime in the Eighties…and on the 1996 Targa Tasmania, Australia’s famous five-day road rally. Team Shep, the brains behind the E-type’s world record.