Forcing the Issue. An historical look back at automotive and aviation forced induction. Forced induction has always been a way to increase an engine’s power. However, rapid technological advances have transformed the process and added two additional compelling benefits: better fuel consumption and reduced emissions. As Ferrari embraces the future with a new generation of turbocharged engines, it would be understandable to consider forced induction a technology that has featured only briefly and occasionally in Maranello history. In fact, it goes right back to the very first cars to carry the Prancing Horse.

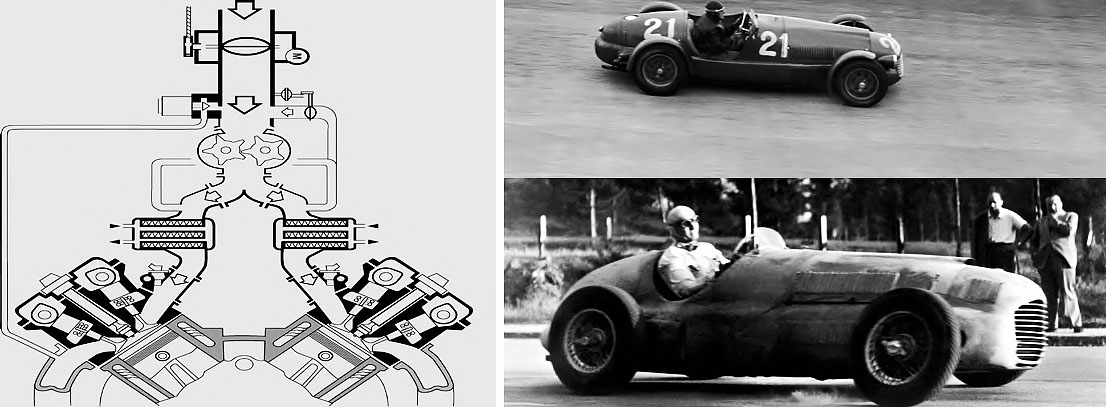

In the pre-war years, the use of supercharging – where the compressor is activated by the engine – was widespread. Left, Louis Chiron in 1935 in the Alfa Romeo P3. Enzo Ferrari experimented with this kind of forced induction for his 1948 125 F1 (middle, right) and the 1949 166 FL (bottom, right). Top right, details of a mechanical compressor.

These cars were not Ferraris in their own right, but Alfa Romeo racing works, run by Scuderia Ferrari as the factory team from 1932. Although Alfa Romeo first started supercharging racing cars as far back as 1924, its greatest pre-war successes came with the likes of the Tipo B, whose supercharged straight eight engine sat under a bonnet wearing the famous Ferrari shield as it raced to victory after victory, and the 158, whose exploits can be read about on the following page.

“More air pumped into an engine delivers greater power”

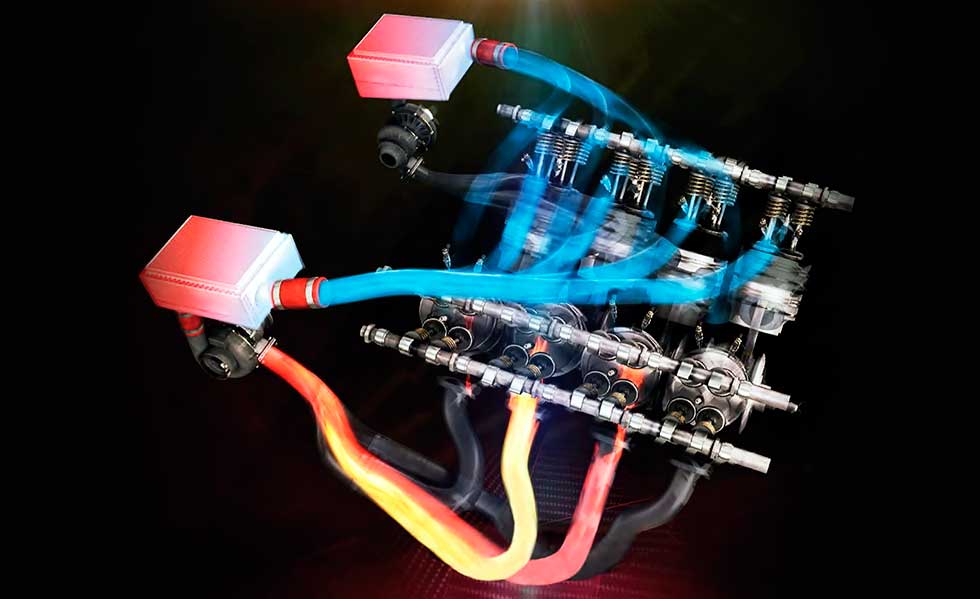

The appeal of forced induction engines is obvious: using an external air compressor, more air can be pumped into the engine, allowing it to burn more fuel and deliver more power. In the early days, compressors were driven by the actual engine but, as this required considerable horsepower to power it, turbocharging has been favoured ever since: the turbine is spun by the exhaust flowing from the engine.

Although considered automotive technologies today, both turbocharging and supercharging can trace their roots back to the aircraft industry, where they were used to combat the powersapping effects of decreasing air-density at altitude. And, while the supercharger made it into cars long before the turbocharger, even this latter technology is older than you might think: if you like automotive trivia, remind your friends that pole position for the 1952 Indianapolis 500 was achieved by a car powered by a turbo-diesel engine, more than 20 years before the first turbocharged production road car.

“Lancia turned to Ferrari for a purposebuilt race engine”

The reason so few turbocharged cars feature in Ferrari’s history is that the turbocharger comes with some inherent problems, which only recent technological advances have addressed. The issues included non-linear power delivery, slack throttle response and a dull exhaust note. This meant that, in the past, Ferrari used turbo engines only in response to two very specific and unusual requirements.

The first of these need not delay us for long. It was simply a policy in Italy during the 1970s and 1980s to increase tax on engines of over 2.0 litres. Ferrari’s initial answer, a 2.0-litre 208! GT4 and 208 GTB, lacked the power for proper Ferrari performance, so from 1982 a 208 GTB Turbo was produced that provided acceleration similar to the normally aspirated 308 GTB. The GTB/GTS Turbo, a 2.0-litre turbocharged version of the Ferrari 328 GTB, was also made available in 1986 offering an impressive 254hp. Production ceased in 1989.

A schematic of a twin turbocharged engine. Here the turbine is spun by the exhaust flowing from the engine, thus recovering power otherwise lost.

However, there was another reason for Ferrari to start using turbocharging in the 1980s, where the primary requirement was for an engine boasting extreme power, but of compact, lightweight dimensions.

Most obviously this meant Formula One. By 1981, it became clear that far more power could be achieved with a turbocharged 1.5-litre engine than the normally aspirated 3.0-litre engine that was also permissible under the regulations. In its very first year as a manufacturer of turbocharged F1 cars, Ferrari won two races, before winning the Constructors Title in 1982.

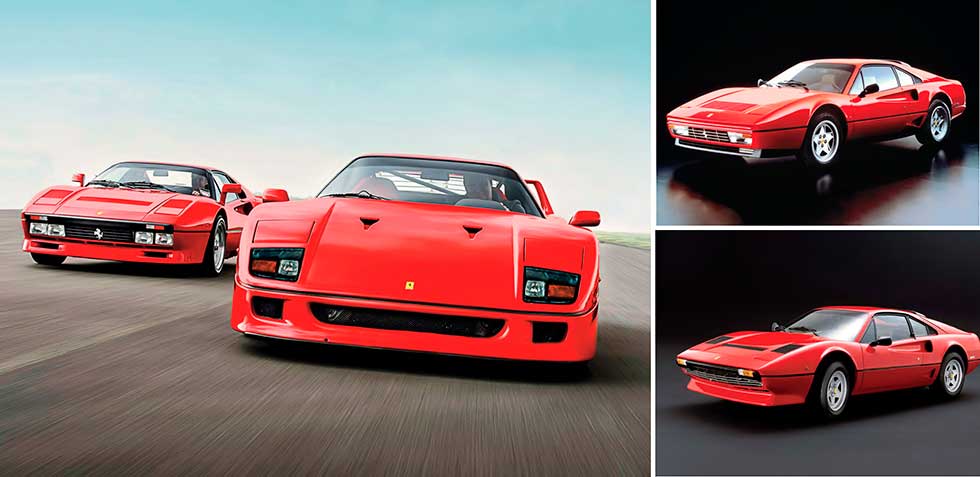

Ferrari’s most revered and remembered turbocharged creations are a brace of road cars designed in the 1980s that started a lineage of special series, ultra-high performance road cars whose line continues with the LaFerrari. The first of these was the GTO of 1984, more commonly known as the Ferrari 288 GTO, to distinguish it from the 250 GTO of the 1960s.

Above, a Ferrari F40 alongside its predecessor, the 288 GTO. Both cars were turbocharged to great effect. Below left, the 208 Turbo and, right, the GTB Turbo. Between one model and the other, an intercooler was introduced, designed to reduce the temperature – and increase the density – of air destined for the combustion chamber.

Originally conceived as a homologation model to compete in a Group B car series that never happened, it was launched in 1984 and superficially looked as if it was based on the Ferrari 308 GTB road model. In fact it was an entirely different machine with a longer wheelbase, longitudinal engine and gearbox, no shared panels and body constructed mainly from plastic and Kevlar. Another popular misconception is that the GTO used a turbocharged version of the 308’s V8 engine whereas, in fact, the two motors were actually only distantly related. The engine had a far closer cousin, but it wasn’t in a Ferrari and it wasn’t originally intended for road use.

In 1983, Lancia decided it wanted to compete in endurance sports car racing under the new Group C regulations of the era but lacked a suitable engine. So it turned to its Ferrari stablemate and asked for a purpose-built long distance race engine. As the rules of Group C were governed by a fuel consumption formula, a turbo engine was deemed best for its size, power and ability to tailor the engine’s output (and thus consumption) by raising or lowering the turbo boost pressure of the engine, according to conditions.

Because there was no fuel limit in qualifying, the Lancia could run at maximum power throughout, while if in the race poor weather or a safety car resulted in better than expected fuel consumption, the driver could turn up the boost whenever conditions improved and enjoy more power than an equivalent normally aspirated engine. The resulting car, the Lancia-Ferrari LC2, was arguably the fastest sports model of its era.

This then is the engine that was adapted for road use in the GTO, where with a 2.8-litre capacity it developed 400hp. While this is some 160hp less than offered by today’s least powerful Ferrari, at the time it made the GTO the most powerful road car in Ferrari history, the first to reach 100km/h in less than five seconds and a top speed of 304km/h.

“The mesmeric F40 had a howling exhaust note”

The GTO was such a success that, despite intending to build only the 200 units required to homologate the car for racing, some 272 were eventually constructed. For all its beauty and brilliance, the GTO was also an experiment to find out whether buyers would be prepared to pay very serious money for a limited edition, ultra-high performance Ferrari model. When it became clear that they would, thoughts turned to a far more extreme car, which would not only be faster than any previous Ferrari, but any previous car altogether.

The Ferrari F40, the last car commissioned by Enzo Ferrari himself and launched to coincide with the Company’s 40th anniversary in 1987 was a fitting tribute to the greatest creator of sporting road and competition cars the world has ever known. Unlike the comparatively civilised GTO, the new Ferrari F40 would be a racing car built for the road, a completely stripped out, nocompromise machine that would set new standards not simply of speed – but also of driving excitement.

At its heart lay a 2.9-litre turbocharged engine, a motor that was derived directly from the GTO’s powerplant but with far more power (478hp) and torque fitted into a car that was 60kg lighter. The result was a road car capable of reaching 100km/h in an unprecedented 3.8sec and the first to have a documented and verified top speed of more than 320km/h.

So, while the GTO felt truly memorable to drive, the F40 was simply mesmeric. Every journey was an adventure, characterised by flame-spitting exhausts, a howling exhaust note and stupendous acceleration. The car was so visually and aurally intimidating that many of its owners might never have discovered that, when you pushed it to its very limits, it was a surprisingly faithful car to drive fast. Although it was never intended to be a racing car, it was successful on the track long after production ceased, winning global sports cars races as late as 1995, eight seasons after it was first announced.

As wonderful as those cars were, it would be another generation before turbocharging technology had been refined to the point where it could ever be considered for use in standard series Prancing Horse road cars.

Now they can be made to sound and respond as a Ferrari engine must, a new dawn is on the horizon, heralding not only minor fuel consumption and emissions, but more power from a given engine capacity than ever before.

From left, Michele Alboreto in action at the wheel of the turbocharged 1.5 litre F1/87 in Austria, 1987; Gilles Villeneuve, in 1981, claims Ferrari’s first victory with this type of engine; Kimi Räikkönen in pre-season testing at Barcelona in the SF15″T, which, in line with regulations, has a single turbo engine.