This 1971 BMW Alpina 3.0 CSL B2S E9 is a very significant and rare motor car. Finished in eyeball-searing Inca Orange, it is one of the first 169 CSLs. All these early cars were carburettorfed lightweights, built to homologate the model for the European Touring Car Championship.

So that makes this one an ultra-lightweight, 135kg lighter than later CSLs, most of which were re-fitted with the weighty ‘City Pack’. That burdened them with electric windows, power steering, chrome bumpers, glass side windows, a cable release to replace the bonnet pins, sound deadening and thick carpeting. The springs and dampers were softened, too.

So this 1971 first CSL iteration is the purest and the most motor sport-focused, leading straight to the CSL racing cars that enjoyed great success. But this example is not just one of the 169 factory-spec CSLs. It is an Alpina B2S, developed with even more modifications, all road-legal. Chassis number 2211724 was supplied directly to Burkard Bovensiepen’s Alpina tuning company, where his team set about it. It already featured the lightweight steel body (you can check that by gently depressing the centre of the roof), aluminium doors, bonnet and bootlid with simple opening stays, fixed rear Perspex side windows, no front bumpers (the rear ones are glassfibre) and definitely no heavy City Pack.

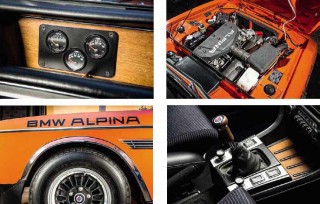

The six-cylinder engine was then given the full Alpina treatment: forged high-compression pistons, big valves, high-lift cam, triple Weber 45DCOE carbs, a tuned tubular exhaust manifold and a road version of the racing ZF five-speed gearbox. Adjustable front and rear anti-roll bars were fitted along with progressiverate springs, Bilstein dampers, a 45% locking differential with oil cooler, and larger ventilated disc brakes all round behind the intricate 8x14in, split-rim alloys.

The result? A lusty 250bhp in a tied-down chassis, and the promise of 0-60mph in 6.6 seconds and a top speed of 151mph, faster than the Aston Martin V8 of the day. This was a roadgoing racing car in its purest form.

BMW Motor Cars started to really come good in the late 1960s, with the arrival of the 2002 sports saloon and elegant Grand Touring CS coupés. The previous Neue Klasse BMW saloons of the early ’60s were hardly ‘ultimate driving machines’, being rather dull and sensible. But when stylist Wilhelm Hofmeister’s E9- series 2800 CS was unveiled in 1968 (it was effectively an enlarged version of 1965’s 2000 CS, with two extra cylinders and a much more assertive nose), classy elegance came to the fore.

In 1971 the BMW 3.0 CS and its fuel-injected CSi sibling were launched with a 2985cc version of the company’s signature straight-six. Now the Bayerische Motoren Werke had a top-flight, sophisticated machine to take on the best from Stuttgart. But a little added vim is always a good thing, and that’s where the privateer Alpina outfit stepped in to continue BMW’s successful Touring Car campaign with the E9. BMW had quit Touring Car racing after the 1969 season with its 2002 Turbo, but Alpina was ready to step in and its mildly modified CS coupé finished ninth overall at the 1969 Spa 24 Hours.

In 1970 Alpina formed the backbone of the E9 racing effort and ran cars in some ETCC rounds as well as the German championship. The engines now produced 300bhp through their triple Weber carburettors; this and the lightened shells helped towards victory at Salzburg and Spa against the Ford Capris. Sadly, though, the Alpina effort was withdrawn from the Nürburgring that year due to tyre problems.

In 1971 Schnitzer joined Alpina on Europe’s racetracks, but Ford had got its act together and was dominant that year. In 1972 BMW poached Jochen Neerspasch and Martin Braungart from Ford to set up a works motor sport department, but Alpina continued its own campaign. This bore fruit in 1973, the Alpina driven by Niki Lauda and Brian Muir winning at Monza against Capri drivers Jackie Stewart and Jody Scheckter. BMW’s works team went on to take six ETCC titles between 1973 and 1979.

Ultimately the CSL evolved into the slightly mad ‘Batmobile’ with its deep front spoiler, air splitters atop the front wings, a full-width roof spoiler and a huge rear wing. As for Alpina, it’s worth noting that its cars were sold with full BMW warranties, such was the mutual trust that grew from Alpina’s motor sport relationship with BMW. The same is true today, the latest models now branded simply as Alpina – a motor manufacturer in its own right.

Outside motor sport, BMW also became synonymous with pop art in the 1970s through the BMW Art Cars. Which leads to the longrunning debate in the classic car world about whether rare and collectable historic cars are artworks. Or, at least, automotive art.

French racing driver Hervé Poulain pushed this along by commissioning American artist Alexander Calder to paint the first BMW Art Car, a 3.0 CSL that Poulain then raced at Le Mans. Since then, artists including David Hockney, Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol and Jeff Koons have created further BMW Art Cars. We shall return to this shortly…

In the metal, the orange B2S looks every inch a sports car of the 1970s. There’s no front bumper, just a neat black spoiler. Those fat alloys are shod with period-correct 205/70 VR14 Michelin XWX tyres. BMW Alpina signage adorns each front wing. The sharknosed B2S looks aggressive, of course, but Hofmeister’s elegance of line still shows through with the airy coupé glasswork and just enough bright metal to be redolent of the time. And it is immaculate.

This B2S was found by BMW guru Barney Halse of specialist Classic Heroes. ‘It spent most of its life in Switzerland,’ he says, ‘and was re-painted white some time in the ’80s. That was common because these bright colours of the ’70s fell out of fashion then. A friend of mine in France discovered it about ten years ago and it was in very good shape. Apart from the respray it was totally original, retaining all the lovely rare Alpina bits. None of the body panels had been removed and it was rust free, which is very unusual with the E9 cars.’

Barney was clearly thrilled with the find. ‘We restored it using all the original components, right down to the rare Scheel seats, the Britax racing harnesses as fitted by Alpina and the additional instruments for oil and axle temperatures. Now it’s back in the original Inca Orange, it’s one of the best examples of a B2S I have seen. The only thing we had to replace was the exhaust but it’s an exact replica of the Alpina system. Then we went carefully right through the car and detailed it.’

This 1971 CSL predates the first Art Car, but there’s a relevance to its pop art looks because it’s owned by international contemporary art curator, pundit and dealer Kenny Schachter. He attempts to articulate the CSL’s appeal: ‘My background is in industrial design, so as well as art I love functioning mechanical creations,’ he explains. ‘Naturally I love cars aesthetically as well as for the physical experience of driving them, which can involve sweating and suffering. And I like cars inside.’

What does he mean? Two things, actually. ‘I like having them inside my space where I live and work, and I like the inside of classic cars with their simple structures and alive odours.’ We have met at Kenny’s central London home. It’s also his vaulted gallery, creatively paint-spattered studio, office and motoring mews. When I walk into the gallery full of huge contemporary paintings I realise just in time that the weird-looking plastic chairs are not for sitting on. They are an ‘installation’, and the back-to-the-future sidelights are not just for mere illumination.

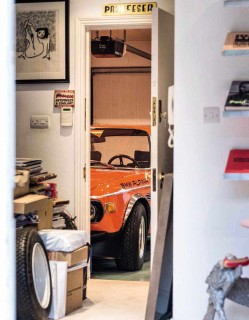

Kenny’s interest in cars is so intense that his office is actually in the mews garage. His desk and computer are surrounded by the exciting shapes and smells of a Porsche 911 RSR, a Lancia Fulvia 1.6 Fanalone Lusso, a Fiat 124 Abarth and the lurid BMW Alpina. ‘I like street versions of racing cars because I drive them on the road,’ he says, ‘but they still have that focused race car set-up that’s so challenging.’

It’s time to get the B2S out to see what all the fuss is about. The four-seater coupé is not a big car by today’s standards but you can see why BMW and Alpina had to work so hard at cutting the standard 3.0 CS’s ample 1165kg kerb weight. The aluminium door swings open with lightweight ease, bar a touch of snagging from the pillarless window arrangement.

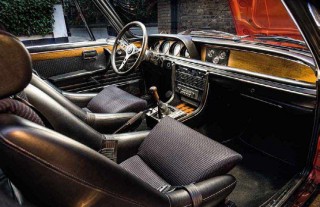

The Scheel bucket seat is extremely tight and heavily bolstered, so once ensconced it’s a bit of a fight to climb back out again. But the seat centres are trimmed in grippy cloth and you’re strapped in tight via the fiddly British-made harness. The drilled steering wheel with its Alpina crest juts out at an angle and is set high complemented by a wooden gearshift knob topped by another Alpina badge. The instruments are BMW’s usual functionallooking VDOs, with extra Alpina clocks mounted in the centre of the wood-trimmed dashboard to register oil temperatures in the engine and rear axle. Very racing car…

I give the Webers two pumps of juice and start the big six. The engine is loud and forceful. It is mostly unsilenced and wants to spin up much more quickly than the docile and refined unit of a standard BMW. The clutch is firm and springy and first gear is positioned towards me and back, on a dogleg. With no power assistance the steering is heavy when manoeuvring. It lightens up on the move but is not one of the sharpest controls in the package. The seating position gives a good view down the long bonnet and the CSL is easy to place on the tight London streets.

Changing up through the gearbox, a fivespeed ZF unit in place of the standard, undergeared Getrag four-speed cog-swapper, leaves no doubt that this ’box is a tough and functional affair. It requires long, deliberate movements and is accompanied by quite a whine from the layshaft.

The Alpina engine, though, is glorious and very evidently a pure racing engine untroubled by restrictive exhaust back-pressure. It wants to climb straight up to the 6500rpm limit, becoming ever smoother as the revs rise. That said, this is a grunty, old-school straight-six which doesn’t bother with creamy refinement. It’s much more aggressive than that.

The big six seems more British than German in operation, like a six you will find in a C-type Jaguar or an Aston Martin DB5. The triple Weber carbs respond with an instantaneous reaction to the slightest kiss of the throttle pedal, unlike slower, more-modulated 1970s fuel-injection systems. And the big valves and high-lift camshaft allow the unit to breathe deep and long. It shoves the lightweight CSL down the road with controlled aggression and soundtrack absolutely, deliciously unfettered.

As we escape London in the evening, the roads open up and the throttle can be pushed down to the stop, sharpening the bellow into a howl. Now I’ve got used to the industrial gearbox, driving the lusty BMW is a highly, physically enjoyable affair.

The previously jittery suspension smooths out as the speed rises. Now the Alpina feels flat, balanced and secure through fast corners as it attacks the roads, powerful all-round ventilated disc brakes adding welcome assurance. A final test, heading firmly into a traffic-free roundabout, shows this balance to be beautifully complemented by snatch-free oversteer through slow corners courtesy of the limited-slip differential.

This ultra-light Alpina B2S is a pure-bred, analogue thoroughbred that’s intoxicating to drive. It combines the attributes of one of the finest BMWs ever made with the responsiveness of a racing car car for the road, thanks to the attentions of one of the best German engineering outfits of all: Alpina.

THANKS TO owner Kenny Schachter and Barney Halse of Classic Heroes (www.classicheroes.co.uk).

‘THE ROADS OPEN UP AND THE THROTTLE CAN BE PUSHED DOWN TO THE STOP, SHARPENING THE BELLOW INTO A HOWL’

TECHNICAL DATA 1971 BMW Alpina 3.0 CSL B2S

Engine 2985cc, SOHC straight-six, triple Weber 45DCOE carburettors

Power 250bhp @ 6500rpm

Torque 200lb ft @ 5500rpm

Transmission Five-speed ZF manual

Steering Worm-and-roller steering box

Suspension Front: MacPherson struts, coil springs, anti-roll bar. Rear: semi-trailing arms, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar Brakes Ventilated discs all round, servo assisted

Weight 1165kg

Performance 0-60mph 6.6sec

Top speed 151mph

Clockwise from far left Looking small next to today’s bloated SUVs, Alpina goes on a night-time London prowl; owner Kenny Schachter’s other orange artwork; author Coucher blunders headlong into kinetic graffiti-fest. Facing page, clockwise from top Race-flavoured cabin hints at Alpina’s purpose; engine is almost in race tune; ZF gearbox has industrial-grade shift quality; Alpina-specific wheels, arches and signwriting; vital extra dials.