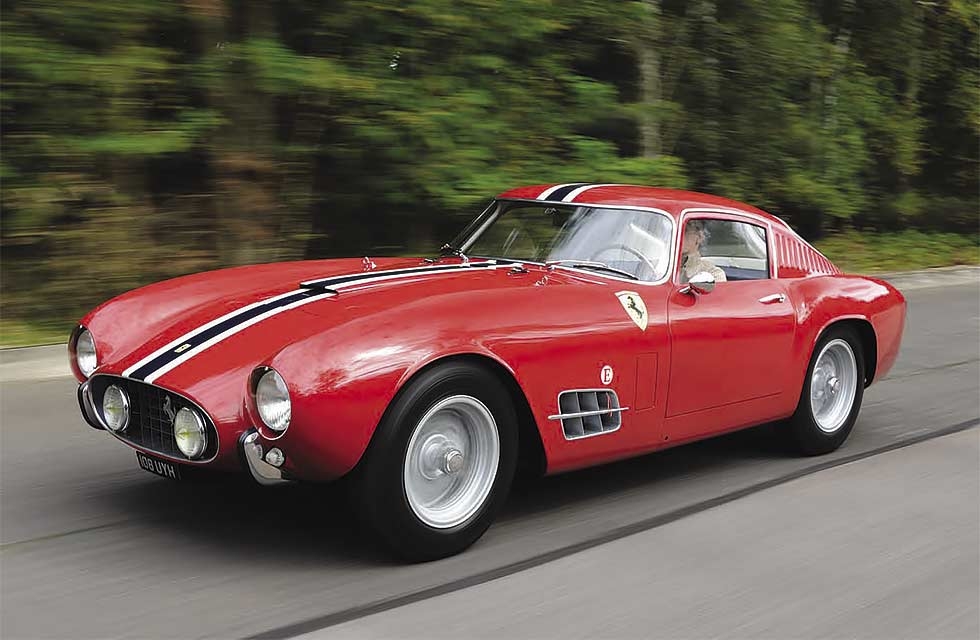

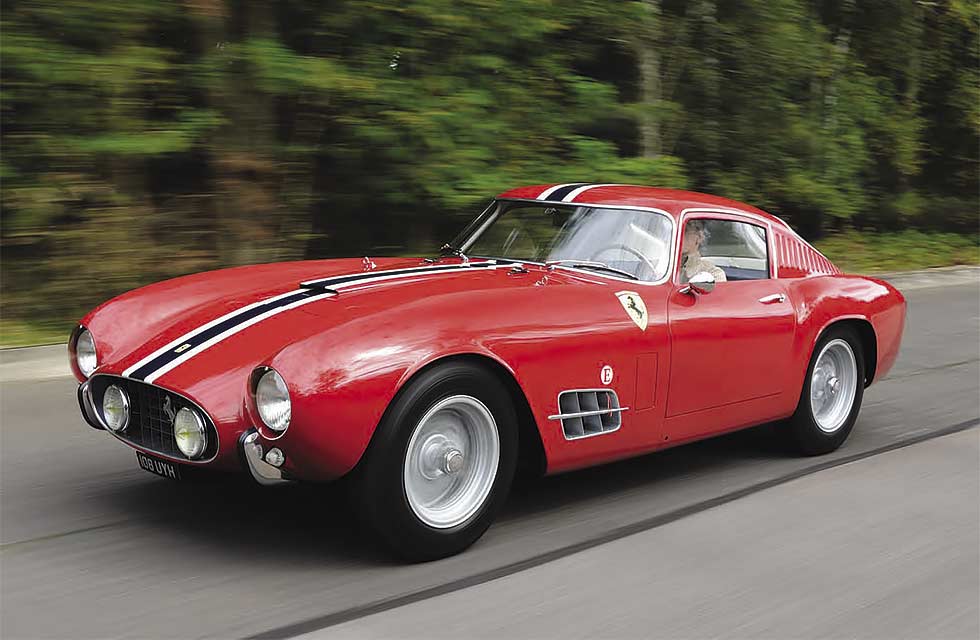

Film Star Ferrari Once owned by Walt Disney Studios this ‘14-louvre’ Coupe added a touch of class to the film The Love Bug Story by Richard Heseltine. Photography by Michael Ward.

FERRARI 250 Tour de France Herbie’s co-star from ‘The Love Bug’

Ferrari Film Star 250 GT TdF co-star from The Love Bug

There is a very real possibility that this will end in tears. The McLaren GT test team is making its presence felt trackside, a blur of orange and black streaking past us as though we’re standing still. It’s followed shortly thereafter by a Porsche of some description, the eejit at the wheel receiving high-performance-driving tuition. Judging from his inability to locate the apex – any apex – thus far, heaven knows he needs it. Past the paddock area and… Oh good, the West Surrey Racing British Touring Championship team is descending upon us, a trio of be-spoilered BMWs filling the mirrors of our mobile chicane. There is a time for heroics and clearly this isn’t it. Nobody else out there has insured a car for eight figures – and that doesn’t include a decimal point. Now might be a good time to stop for lunch.

The funny thing is, ‘our’ Ferrari 250GT Tour de France isn’t embarrassed out there despite the considerable age gap between equipment: the issue is the paucity of balls on the driver’s part. This glorious machine may have aged a little, but it certainly hasn’t diminished: it’s quick for its age, quick for any age. But then that is to be expected as the ‘TdF’ in marque speak was a major weapon in Ferrari’s arsenal in period. Driven by a roll-call of stars and gentleman drivers alike, it claimed more than a few scalps – and not just on the circuits.

It may have been ‘only’ a GT car, but this category took on greater emphasis following the horrific accident that claimed 79 lives at the 1955 Le Mans 24 Hours after Pierre Levegh’s Mercedes was launched into the crowd. As we all know by rote, the after effects of this grisly accident were seismic with everyone from politicians to the Pope passing judgement. In order to kerb speeds, the Commission Sportive Internationale (CSI) governing body responded the following year by placing greater emphasis on the Gran Turismo category. Production car-based machines would now take centre stage once again. What’s more, Ferrari had just the machine for the job having unveiled its new series-manufacture 250 GT at the March 1956 Geneva Motor Show, complete with a 220bhp 2953cc ‘Colombo’ V12.

The car on display in Switzerland featured an elegant body by Felice Mario Boano. This would in turn act as the jumping off point for homologating a competition variant, the chassis and running gear providing the basis for a new strain with bodywork designed by Pinin Farina and shaped by Carrozzeria Scaglietti. And what a body, the coupé outline being both muscularly elegant and reasonably light thanks to the use of thin-gauge aluminium and other weight-saving measures such as Perspex glazing. Officially known as the 250 GT Berlinetta, the prototype placed fourth overall and first in class on the April ’1956 Giro di Sicilia thanks to the efforts of Oliver Gendebien and Jacques Washer. Later that same month, the Belgian duo was fifth on the road on the Mille Miglia while once again claiming class honours.

However, the event that would come to define the model occurred in September of that year. The Tour de France Automobile was a gruelling week-long event that encompassed six circuit races at venues such as Rouen and Monthléry, two hillclimbs and several high-speed road sections. The event wasn’t staged in 1955 following the Le Mans disaster but returned in 1956 with Marquis Alfonso ‘Fon’ de Portago and Edmont Nelson driving chassis 0557 GT to an outright win following 3600 competitive miles. And, at a stroke, the car became colloquially known as the 250 GT ‘Tour de France’. Just to prove the model’s prowess as a long-distance racer, Gendebien went on to take a hat-trick of wins on this event from 1957-1959 while also finishing third overall on the ’57 Mille Miglia. If that wasn’t enough, he teamed up with Paul Frére to win the ’57 Rheims 12 Hours overall, the same pairing repeating the feat a year later. Not bad for a GT car.

Indeed, following Gendebien’s 1957 Tour victory, Autosport commented: ‘Undoubtedly, the 250GT Ferrari proved itself to be an ideal machine for an event which places a premium on performance on race circuits and speed hillclimbs’. They went on to add: ‘The Trophy de Portago, awarded by the Parisian Los Amigos club for the meritorious performance, was given to Gendebien’.

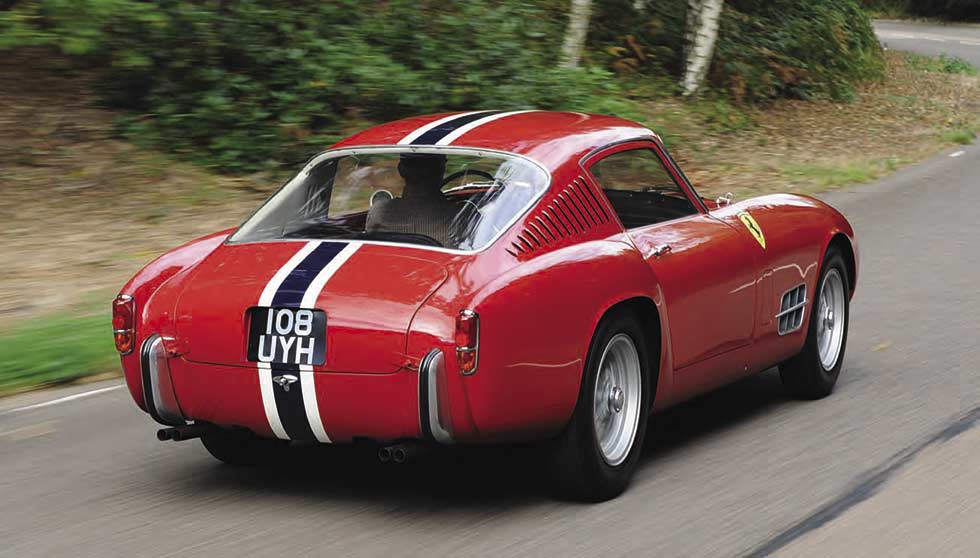

As is to be expected, no two cars were ever truly alike. Following the introduction of the short-wheelbase 250 GT towards the end of 1959, the outgoing platform became retrospectively known as the ‘long-wheelbase’ version. Through its brief production run (1956-1959), the TdF went through various physical reconfigurations which ultimately resulted in four different series-produced body styles (and that doesn’t include as many as five Zagato-bodied cars). These divergences are most obvious when viewing the rear bodywork, in particular the Cpillars: early cars had no louvres, the second-series strain had 14, the third strain had three and the final run featured just the one louvre either side. Of the quartet, 14-louvre TdFs are the rarest, with only nine examples made, and many arbiters of beauty believe they are the best-looking. It’s all relative.

The example pictured here was the first example constructed of the second series design. It was delivered new on November 15, 1956 to racer/entrant Tony Parravano. This West Coast construction magnate was well known for fielding a mouth-watering array of exotica in Sports Car Club of America (SCCA) events. That, and for disappearing from view four days before he was due to appear in federal court to face charges of tax evasion. Chassis 0585 GT was entered for the Palm Springs road races in early April of 1957, only to be disqualified because the SCCA refused to recognise it as a production car. Following its owner’s vanishing act, the car remained in Southern California (unlike some Scuderia Parravano racers which surfaced years later in Mexico…). It subsequently changed hands a few times before making its bid for motor sport immortality on being acquired by Walt Disney Studios for use in 1968 flick, The Love Bug.

After having its backside handed to it by Herbie the all-conquering Volkswagen Beetle, 0585 GT fell on hard times. Once the film was in the can, it passed through various hands before being reputedly spotted abandoned by the side of the road near Hollywood in the early 1970s. Fast-forward to 1994 and the car resurfaced and was restored in the UK by DK Engineering, the TdF making its big reveal at the 1997 Coys International Festival race meeting at Silverstone. It was sold in October of that year to American enthusiast Jon Masterson for $925,000. The California-based collector drove the car in numerous historic events including the Tour Auto, the Mille Miglia retrospective and the 2000 Shell Ferrari/Maserati Historic Challenge race at Le Mans. In 2012, it was sold for $6.71m to marque specialist Talacrest, which in turn supplied the car to a Swiss collector. Talacrest took the car back in a deal in 2013 and sold it to an British enthusiast – who then traded the car in as part of a deal involving an aluminium-bodied competition 250SWB – leaving Talacrest to offer it to another British collector a few months ago.

Which brings us to today. With the track free and clear, it’s time to venture trackside once again. From inside, the Ferrari’s cabin is spartan, clean; no frills. The driver’s bucket seat is mounted relatively low, the view past the wood-rim Nardi wheel – past the vast rev counter and speedo – and across the acreage of bonnet being life-affirming before you so much as crank the engine. It’s quite a sight. And what an engine: there’s always a sense of theatre when starting a classic Ferrari and this one doesn’t disappoint. The V12 fires with fanfare but without the expected histrionics. It sounds epic, all gnarly, pent-up fury. It’s the polar opposite of modern day Ferraris with their flat plane crank parps.

Press in the stiff clutch, select first and, following a clumsy bunny hop, we’re moving. The Tour de France feels as though it is straining at the leash. It wants to move quickly, and it wants to do so now. Once trackside, it accelerates with alacrity: in period, Ferrari claimed the TdF produced an honest 260bhp, enough of the good stuff for a 0-100mph time of 16 seconds and top speed or around 140mph. For once, the factory stats appear believable. While it might not be the easiest of cars to drive slowly, not least because it’s clearly unhappy chuntering away in a low gear, it’s pretty easy at speed. Anyone well-versed with old cars could drive it someway south of ten-tenths without tripping over themselves.

The engine dominates the experience. Bury the throttle in second, sweep past 5000rpm and it sounds as though the V12 is spinning off its axis. It’s probably a case of perception rather than reality, but there appears to be little rotational inertia. It just revs and revs and then revs some more. Some reports claim the gear change is ponderous and notchy, but that just isn’t the case. You cannot make lightening changes, and nor can you be tactile. You have to be firm and expect some firm resistance across the gate, but it’s next to impossible to grandma a gear shift. The steering is surprisingly well-weighted, but you change the car’s direction as much with the throttle as the wheel: arrive at a corner, lift a little, hit the apex and then power out with the tail stepping out ever so slightly. This isn’t the driver acting the big man and coming over all ‘Earl of Oversteer’. It’s merely the car’s natural cornering attitude and it isn’t remotely intimidating. As for the drum brakes, well they require quite a shove before they bite but they don’t threaten to fade.

It’s an inconvenient truth, but some early Ferraris are – whisper it – rather unpleasant to drive. If experience teaches us anything, it’s that most of them don’t get driven much further than the end of their owner’s driveway and, as such, they tend to throw hissy fits when pressed into service. That isn’t the case here. This car feels beautifully set-up and, as such, you want to keep driving it. The prospect of doing a Gendebien and racing one flat chat for 3000 miles or more is perhaps pushing it: the cabin gets very toasty very quickly, and you would probably be deaf by flag fall. But, and it’s an important but, we’re struggling to think of another GT car of the period that can match it for either pace or beauty. It really is in a class of one. It always has been.

Thanks to: John Collins www.talacrest.com

FACING PAGE: Clear signs of the Ferrari 250 GT’s evolution as the ‘Tour de France’ version morphs into the later 250 SWB. ABOVE LEFT: Clear recognition of the car’s unofficial ‘14-louvre’ title. BELOW: Rear wings are tidier than the first series 250 GT ‘Tour de France’.