EPIC READER RESTO!

Some men and their machines are destined to stay together for ever. Take Paul Tarrant and his muchtravelled Vauxhall PA Velox. “The speedometer is now showing 55,568 miles for the third time,” he says. “It’s on its fourth engine, and I’ve had the bodywork restored three times.”

A Saab or Volvo running up starship mileages is relatively commonplace, but a ’59 Velox is a different matter: “Like the Mk2 Jaguar, a good PA was always sellable, but from the ’60s through the ’80s the rest were just stock-car fodder. It’s largely luck that some survive and others don’t – the deciding factor is often who owns them.”

Luckily for PJT 22, it landed in the right hands. As a 20-something working in a Bournemouth petrol station, Tarrant was particularly taken by the model: “There were several used as taxis locally – a yellow and white one, and a two-tone blue example. They looked very dramatic and ’50s American. When I bought the July 1976 issue of Custom Car, which featured a black three-piece-rear-window Velox, that was it.”

The following year he found himself at a bungalow in Kinson looking at a Coronado Yellow Vauxhall, 2471 EL, that had been advertised by owner Kenneth Foster in the evening paper. It was mid-series with no MoT, inner sills or wing tops – inner or outer – while the outer sills were also quite poor: “However, it started, moved about, was an attractive colour and it came with a new wing and a set of manuals – all for £70.”

So began the PA’s first bodywork ‘restoration’. “I call it a restoration, but it had a lot of bodging over the years,” explains Tarrant. “When it was fairly worthless you just wanted an MoT. A month and £80 later, I had the precious certificate.”

In 1978, Tarrant acquired a mid-series Cresta bearing the registration PJT 22 and transferred the number, which bears his initials, to the Velox. The swap cost £50 and he remembers many of his contemporaries saying at the time that it was a complete waste of money.

Having fitted the Velox with a tow-bar, he started transporting vehicles for a living before a natural graduation to HGVs, including continental work. His new long-distance driving profession influenced the exotic destinations visited by the Vauxhall during his downtime. “In ’78 it went to Monaco and back,” he says. “It survived that, so I went to Stockholm via Germany and Denmark, where I left my friend Mick at a hippie commune in Copenhagen. A six-week grand tour followed in the spring of 1980: Salzburg, Italy via the Brenner Pass, two weeks in St Tropez and then home – 3500 miles.”

Tarrant had replaced the motor by then, but due to his towing activities – he once bought a Ford Consul convertible in Crewe and lugged it home – that unit lasted only 60,000 miles. Luckily, he found another one at an engine rebuilding firm near Bath: “Someone had ordered a rebuild, paid a deposit and not come back. It was painted blue and was mine for £100. That was in 1982.”

During that summer he set off for the Costa Brava and a three-week holiday, the PA’s overseas adventures continuing right up until its last grand tour in 1996. “Neuschwanstein castle and Innsbruck via Ramsgate, but due to the mild winter I didn’t get the chance to use my snow chains,” he laments. “Although I prepared for these journeys, a serious breakdown would have meant abandoning PJT 22 on foreign soil, and the cost of recovery wouldn’t have been viable.”

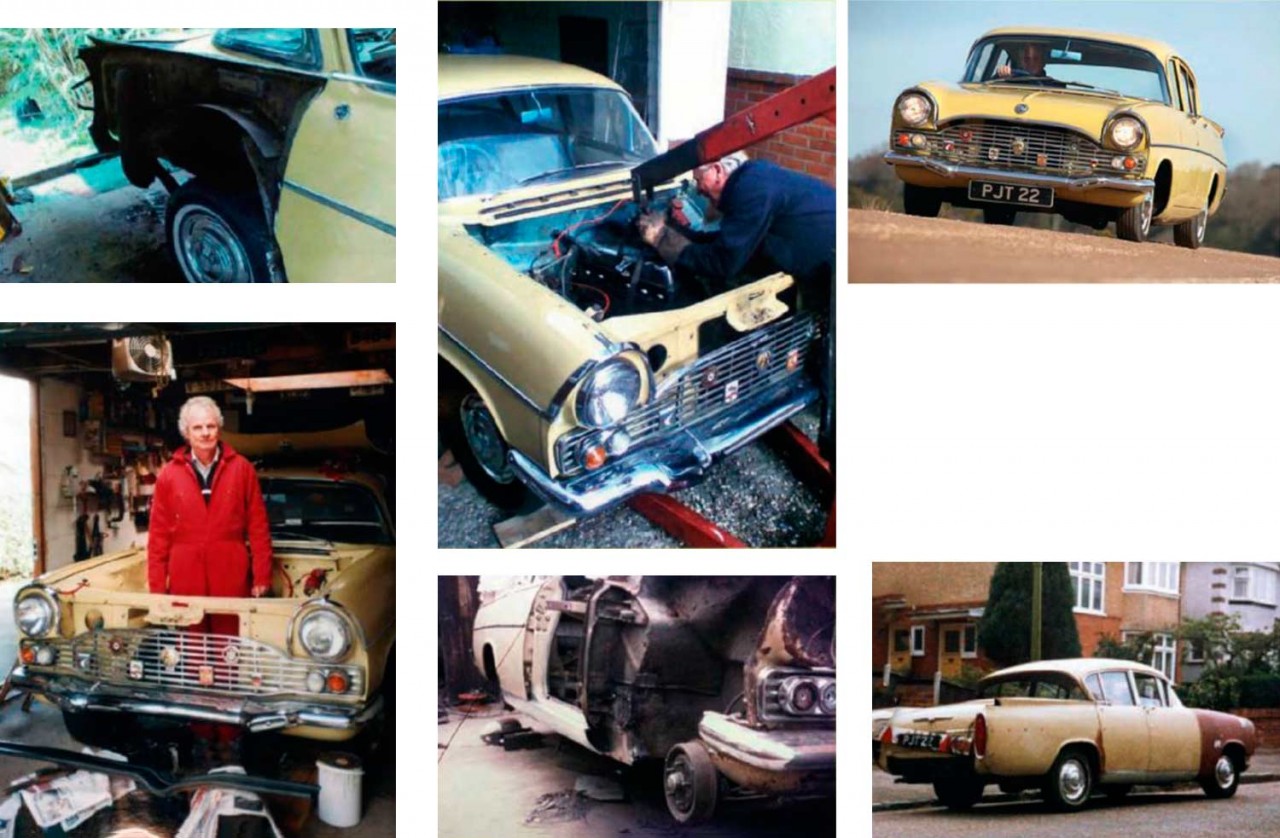

Tarrant used the car as a daily driver right up until 1999, and in ’03 it received a much-needed respray plus a set of window seals. Fast-forward seven years and, in June 2010, the faithful blue engine broke a big end. He sent it to specialist Robinsons of Ferndown, but the news was ominous: “They said the crank was no good, the cam was no good and the bores were no good. Fortunately, in 1996 I’d bought an engine for £5, condition unknown, from a man in Cornwall called Phil Robinson. It had lived under a bush in my garden, but when we opened it up it was standard bore, with a good cam and crank. It saved me about £1000 of machining. It was rebuilt with an unleaded head, and I installed it.”

Over the years, the PA’s propensity for recreating itself led to it gaining the nickname Christine, just like the Plymouth Fury in the Steven King novel of the same name. By that time, the car was fairly sound mechanically, so Tarrant’s thoughts turned to finally doing it justice with a decent body restoration. The previous respray had turned out to be a bad one, with a resultant mosaic effect on the roof while other areas were simply peeling off. Unsurprisingly enough, however, driving the Velox got in the way and it wasn’t until September 2015 that work began in earnest.

Tarrant carried out the stripdown, and then body man Mark Tompkins went to work. “It’d had a lot of work done to it,” recalls Tompkins. “A rear wing had been replaced, and it had accident damage to the nearside front corner. The biggest challenge was trying to fit panels to bodywork that in places wasn’t quite right.”

Tarrant agrees: “When we took the outer sills off, the inner ones were missing altogether; someone had put metal scraps off the floor in there, probably to cut costs. Whoever did it probably thought the day would never come when the outers would be taken off. The doors were awful to fit; the amount of play is minimal, but because my car is slightly bent it’s worse than normal.”

After 40-plus hours of Tompkins’ time, the car went to Stanfield Garage Body Shop – a BMW specialist that also tackles classics. “Initially we weren’t going to take any panels back to the bare metal,” says co-proprietor Steve Coneley, “but in places it must have had 20 coats of paint on it. I’d never seen it that thick. There were also patches, and bits and pieces – some that didn’t need to be there – that had been done over the years, so we ended up going further. Trying to get the back doors to open without opening the fronts was a challenge, as was the bootlid.”

Many parts had no doubt come from earlier and later PA variants, but after painstaking effort the shell was ready for spraying by Coneley’s son Paddy. Local firm Rainbow Paints matched the rare pre-production Coronado Yellow using a spectroscope, and then Paddy set to work.

“The underside and engine bay weren’t touched,” says Coneley. “If Paul had given us £20k we’d have returned a concours car, but that wasn’t what he wanted. It is what it is, an original, usable vehicle that he’s been all over the place in.”

Again, Tarrant is refreshingly honest about the Velox’s journey to this point: “Mark wanted to do the welding because it was such a battlewagon; it didn’t look like it does now. It’s had more than one accident, the heavy stuff before my ownership – I’ve only whacked it twice. The previous owner replaced the rear wings when a lorry hit it, and I did so again in the ’90s after they had corroded.”

Tarrant’s biggest worry was that Stanfield would be unable to match the paint: “I’d kept the car running – selling less rusty examples – because of that colour. It’s unique to me. I’d been to several paint shops, but they couldn’t do it. I thought that I would have to ship it in from the States at massive cost, but they did a great job.”

With the PA back home, he set about the relatively simple reassembly work. Save for a fresh windscreen from the stockpile of spares that he’d built up over decades, the original windows went back in – Tarrant reasoning that, despite having better glass, he’d known them for 40-odd years.

A recored radiator was fitted, as was the original suspension. He also took the opportunity to have upholstery man Keith Harding make some fresh carpets. “Most classics leak around the doors and windows,” says Tarrant, “but a Velox is particularly bad. Water gets in through the vent below the windscreen and, in theory, comes out of pipes on either side by the rear of the wing.”

He remembers parking the PA in the ’70s and ’80s, driving to the continent, and on his return gallons of water coming out the back of the car as he sped off. “I’m sure quite a lot of it just lives in the box areas there, and what does come out dribbles down and pools into the footwells.”

Harding crafted the new carpets from speedboat items, which don’t absorb water like normal fabric and can even be put in the washing machine. Combined with careful door fitting and another set of fresh rubbers, the interior was dry for probably the first time in Christine’s life.

New-old-stock chrome that Tarrant had bought in the ’70s completed matters: “I’m fairly self-sufficient in terms of parts, so to put it back together took around five weeks. Dealing with professional people, albeit more expensive, was much better than blokes in lock-ups. Previously, I just wasn’t doing it to a high standard.”

So where does that leave us today? Well, the answer is, with one of the classic car world’s great survivors and a sight to gladden the heart – just as those social media images of scrappage scheme classics awaiting their maker does the opposite. This Vauxhall wears its scars and life experiences with pride – from the faded engine bay to the marginally different profile on each rear wing (all pointed out by Tarrant, but not noticed by yours truly) – only now with a much better fit and finish.

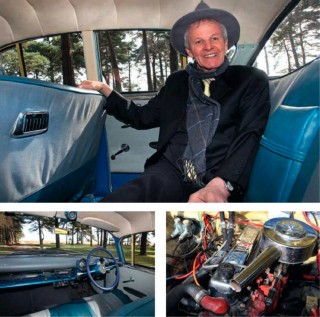

Inside, the interior is non-standard, with the original grey plastic long since replaced with corduroy and vinyl appropriated from a pranged custom car, while the battleship-grey paint on the dashboard has given way to Ford Miami Blue. The PA speedo is identical, if smaller, to that of a 1957 Chevy, the car Paul reckons he should have graduated to by now, and there’s the obligatory three-gauge aftermarket look.

On the road, the 2262cc straight-six is a breathy companion and the column gearchange feels loose but user-friendly. Unlike the tight and sometimes unyielding feel of a concours car, this lends an instant insight into Tarrant’s decades of driving the big Luton saloon.

“He’s done really well to keep it going,” says Ray Charambulous of R&B Garage, who has looked after the car since Tarrant bought it. “It’s had considerable work over the years, but he’s never put any financial limit on fixing it. Whenever he left Bournemouth he’d give me a ring and ask if I could fetch him back if it broke down. I don’t remember ever having to do that, though.”

The Vauxhall’s grand continental tours are momentarily on hold while Tarrant undertakes ‘short’ trips to Edinburgh and the like, but it is only a matter of time until the urge for a big ’un returns. And the restoration decision he made, to keep it rolling rather than take it apart and attack every nut and bolt, feels like the correct one. £20,000 on bodywork would have given him a car that he’d have been afraid to use, and that’s particularly apt given his plans for Christine’s future. “It should never have survived, but it’s had its fair share of luck,” he says. “Mark’s going to fettle the rear wing to resolve that minor issue, the engine bay will be resprayed and then I will just drive it around – and probably have to restore it again in 15 years.”

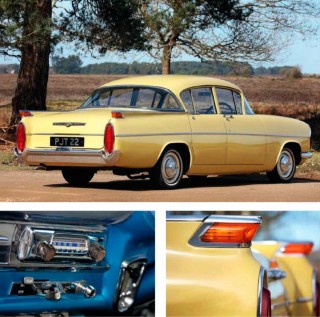

From main: Vauxhall is no sports car but is a pleasant and relaxing drive, and has undertaken some epic pan-European adventures; period publicity material and original buff logbook.

Clockwise: proud owner Tarrant; rebuilt 2.3-litre ohv ‘six’ produces 82.5bhp; cabin has been retrimmed but retains period flavor.

From top: fins ’n’ chrome shape is accentuated by the Vauxhall’s Coronado Yellow paintwork; singlepiece wraparound rear window was introduced on facelifted mid-series cars; period radio in fascia panel.

Work in progress

From top: lowering motor into place in 2010 – the Velox has had four to date; wing and door removed to facilitate repairs in 1979; stripped for surgery in 2015; working on the engine bay seven years ago.