All it took to create the bond between man and bubble was a glance. In 10-year-old Dave Watson’s brain, an electrical spark heralded the formation of this new synaptic connection. “A guy across the road from my mate’s house had one in his garage,” he recalls. “When the door was open, you could see the front of it. For some reason, it stuck in my mind.”

Fast-forward to his teenage years. After passing his driving test, Watson graduated to a Volkswagen Beetle then a number of ‘normal’ cars. In 1992, though, a flick through a copy of a classic magazine prompted the retrieval of that formative memory from the far reaches of his cortex: “It had a general bubble-car feature with a variety of different marques and I can clearly remember thinking, ‘I fancy an Isetta.’”

Having found out about a rally in Epping Forest, he got chatting to a guy with a green one who took him for a run around the show field. Watson “was hooked” and purchased his Isetta at a microcar show in Bath two months later: “I came home, told my dad I’d just bought a car and when I mentioned what it was he said: ‘Why the bloody hell do you want one of those?’”

Watson carried out a full restoration of what he says was a “running wreck” to such a high standard that it became a multi-award-winning show car – it played a starring role on BMW’s Goodwood Revival stand in 2016. During the rebuild process, and subsequent ownership of the car, Watson became involved with the Isetta Owners’ Club and is now a director. He organises the re-registrations with the DVLA and the show stand at the NEC each year, as well as looking after the database for all known Isettas.

“It’s been restored twice,” he admits. “That seems to be the way with me – restore it, paint it and then paint it again. And once it’s done I can’t sell it because there’s so much gone into it.” He’s also an inveterate ‘doer’, so another project was inevitable: “My main enjoyment is working on them; I do like the showing, but it’s secondary.”

So, in August 2005, when flicking through Kabinews – the UK Messerschmitt Owners’ Club magazine – he saw an advert for an original dome-top KR200 Deluxe, and knew it had to be his: “I was looking for one and as soon as I read the description I phoned to get more details. I was the first person to ring by just 30 seconds!”

Watson was told that there was no negotiation on price, but despite a queue of potential buyers the owner would honour the fact that he had been the first to enquire: “It’d been stored since the mid-1980s. It was seized and rusty but the next prospective buyer arrived when I was still there viewing it so I said, ‘I’ll take it’, and paid the £3000 asking price. Despite the vendor having another working example in the garage, his family was in tears because he’d bought it when he was a medical student and owned it from new. I can remember thinking, ‘Let’s get out of here before he changes his mind’.”

With the Messerschmitt back home, Watson set about inspecting it. The car was almost wholly original, but it was very tired and in need of full restoration: “Luckily, that’s something I enjoy doing. The engine was seized and the interior shot, but bodywork-wise it wasn’t too bad – there was rust, but not too extensive. “I thought the process would be straightforward, but how wrong I was to be proved…”

The strip-down began in spring 2006. The engine and suspension units were removed and stored for individual overhaul at a later date. In the meantime, Watson got busy sourcing the many new-old-stock parts needed to complete the project: “It all came apart fairly easily, but I knew it’d be 10 times harder to reassemble.”

The floor of the tub had many small rust pinholes, so Watson decided to replace it. As a welder by trade, he had no qualms about such work. “It was fairly easy to me,” he says, “but I still had to be careful with the dimensions. After much advice, I decided that it was just as simple to replace the whole tub’s sheet metalwork.”

A number of new panels were sourced from the Messerschmitt Owners’ Club in the UK and Germany, and Watson set about building the new tub. To ensure a tight fit, he first tackwelded it – with two or three trial-fits of the nose and engine lid – before welding it up: “I managed to keep the original front crossmember and the top tube from the car, but the rest of the tub was new and I constructed all the small brackets because they’re no longer available. By far the hardest part to repair was the lifting section – I had to make some panels from scratch.”

Watson took the decision to not weld the lifting piece to the side panel, as was originally done at the factory, because he felt that it would be easier to assemble once painted. The original Coral Red paint – “More orange than red” – was sent off for colour-matching and the result that came back was Mitsubishi Ivory Coast Orange: “The nose was painted as a trial and it looked great, so the colour was chosen.”

The bodyshell was then disassembled and sent off for dip-stripping to remove all final traces of surface rust, and E-coating to protect all the panels to a quality far superior than that when the car was new. In all, this ‘easy’ process still took Watson the best part of 13 months. The mountain had been scaled, however, and from that point on the project would be more straightforward – or so he thought.

“I had the tub painted first at my local bodyshop,” he recalls, “with the panels following afterwards; little did I know they’d be there for three years. I wrote instructions as to where the colours should be sprayed because I wanted to replicate the original finish. So ‘neat’ satin grey primer overspray was used and black sections of floor requested. Vital help with details was supplied by club member Andy Woolley.”

Filler was kept to a minimum and a two-pack solid colour application used: “I could have gone down the route of a base coat and lacquer, but I wanted it to look as original as possible. The final paint was done by AV Classics in Dunstable.”

Determined to retain as many of the original components as possible, Watson then embarked on the process of stripping and rebuilding the countless smaller parts: “Literally hundreds of hours were spent cleaning, repairing, polishing, painting and plating.” He researched and remanufactured those bits that were not available new, such as the canopy strap, missing tools and rear-seat storage boxes: “Many were re-made several times until I was happy with them. I’m practically minded, but never satisfied – although I am mellowing the older I get.”

Incredibly, he reckons the above processes lasted right through until the car was finished. In that time, he also made good use of the internet, searching for materials, suppliers and reference photos of original cars: “I’m not of the internet generation, but you just type it in and it’s there! How you used to find out about things before it, I just don’t know.” His friends in the Isetta Club knew of the car and periodically asked after its progress, but it remained slow going.

In the summer of 2009, the engine was stripped down: “It’s married to the gearbox and I found the ’box part quite complicated. I let the experienced Wynford Jones, from the club, do the internal crankcase reassembly.” The cases were vapour-blasted and barrel-coated with heatproof paint, then a new MOC-supplied exhaust was sourced and coated in satin-black ceramic. Watson then refurbished the carburettor as well as the electrical system.

“The reassembly started in January 2011 and took until 2015,” he says. “Its order consisted of tub, wiring loom/cables, front end, pedals, nose, wings, rear subframe, electrics, rear drivetrain – then more bodywork. The amount of time spent on the smallest of details can’t be underestimated. It’s also the point at which you find out what parts you have missing and what new or refurbished ones don’t make the grade.”

The car’s interior was found to have originally been black vinyl with white piping and snakeskin trim. The seats were stripped and rebuilt, and a trim kit bought from club member Nick Poll: “I’d actually been at an autojumble in Germany with Nick when he found – and bought the whole roll of – the snakeskin trim. I asked if I could have the interior made out of it. He sewed up the cushions while I did the side panels.”

He admits that it was at this point he took a break: “If I’m honest it was a pig to restore, an absolute pig. I asked people, ‘How on earth did they put these together in the factory?’ The process was driving me potty, so I downed tools for 18 months because I’d completely lost the will to do it.” The reason, he now admits, is because next up was the lifting section – something that he was dreading.

In April 2016, Watson committed to showing the car at the NEC, which gave the project a sudden and time-constrained impetus: “It also put me in a rush, which I don’t like doing.” Not something that was conducive to perhaps the trickiest part of the restoration: “The dome was made by a chap in Germany and comes as a preformed sheet of very roughly cut Perspex; it’s down to you cut it to size and fit.”

Cue disaster – his first attempt went horribly wrong: “I cocked it up; cut it incorrectly. What can you do? It was an expensive mistake at £1200 a pop. So I rung Wynford Jones again, and he offered to help me mark up a new one – luckily he had a spare – although I still did the actual cutting.” Thankfully, it was a case of secondtime lucky because it fitted perfectly, and with the remanufactured side windows – with knobs fabricated by Jack Veeke in Sweden – the restoration process was finally complete.

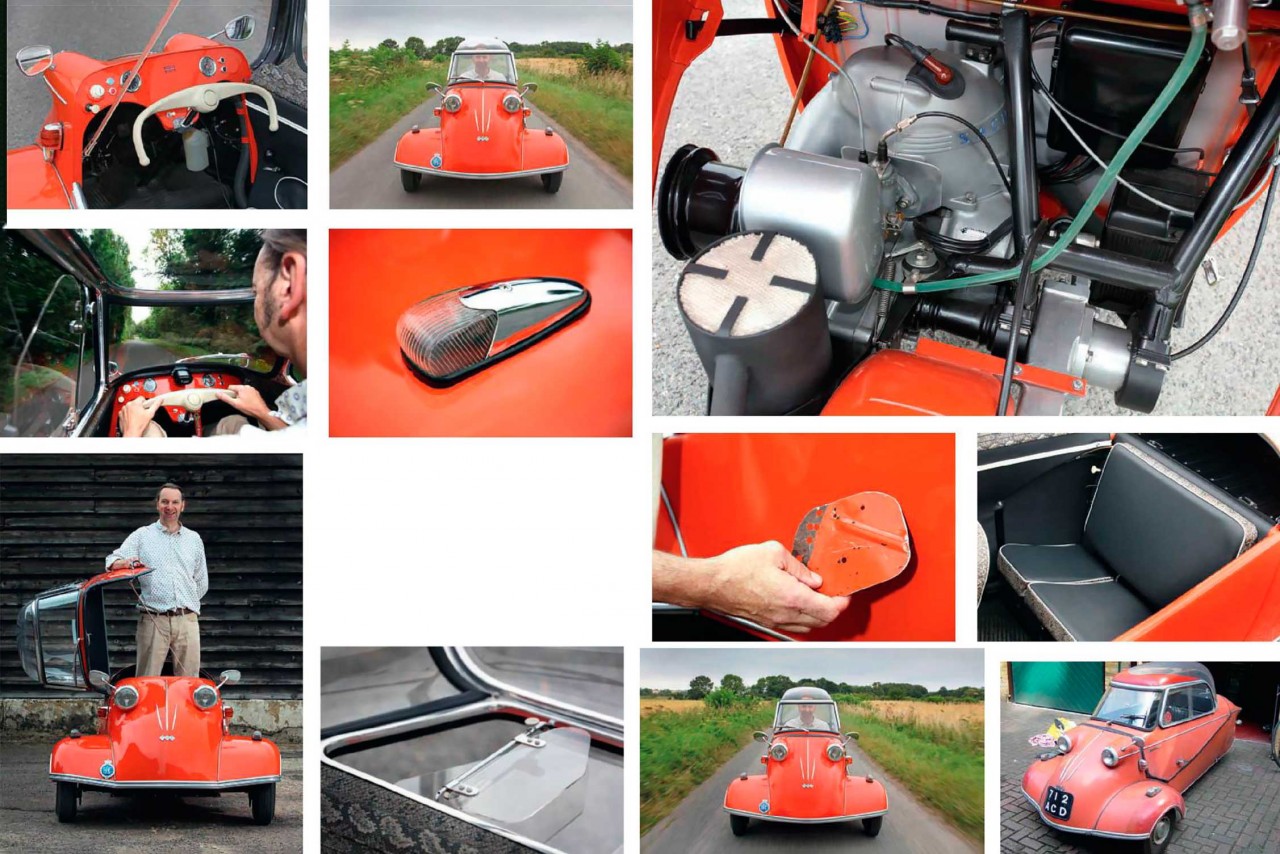

In the metal, the lengths to which Watson has gone are clear, with the KR200 finished to a far higher standard than when new – no wonder it bagged second-best car in show at the NEC: “It’s a real kid magnet, but generally it was very well received by the club, with both positive feedback and constructive criticism offered.” On the road it’s a thing of wonder, with an incredibly light, airy cabin and 360-degree visibility, coupled with a feeling of single-skinned vulnerability. Throw in a 9.7bhp, single-cylinder engine that screams in your ear like Crazy Frog, plus direct steering bordering on the hyperactive, and you can see exactly why these diminutive beasts are such an acquired taste.

Watson is particularly proud of the finish achieved: “Open the engine bay and that’s two years’ work in there. The numberplate I made myself, and it took me a month to complete. There are little bits I’ve stressed over; the wing piping I couldn’t get right. It’s a simple, simple job and yet I’ve had the wings on and off about 10 times and there’s some crafty Superglue in places that only I know about.”

Watson says that the Isetta restoration informed this one, and this in turn will inform the next one: “You get better at what you’re doing. That said, I’d paint the next one all at the same time. I did it in bits and, although it was from the same tin, it came out as 50 shades of orange. I stripped it down again, took it back to the bodyshop and asked them to spray it all one colour. It’s part of its story. You’d never know and I don’t mind; it’s all a part of the laugh.”

All these years on, that formative bubble-car experience is still playing its part. When longterm memories are recalled, they are once more summoned to the front of the queue. And in Watson’s case that inevitably informs what comes next: “Definitely not a Messerschmitt. But I do fancy another microcar.”

If I were the type to dabble in rhyming slang, the obvious answer would be, “You’re having a bubble, Dave”. His response would no doubt be: “Actually, I’m having three.” And naturally, they’ll be three of the best.

“I CUT THE PERSPEX INCORRECTLY, WHICH WAS AN EXPENSIVE MISTAKE AT £1200”

“THE TIME SPENT ON EVEN THE SMALLEST DETAILS CAN’T BE UNDERESTIMATED”

Work in progress

Chassis tubes were covered with new metalwork Watson was specific about where to spray the tub E-coated component parts ready for final painting Reassembly under way: Watson made a new loom Wooden dolly came in useful during final stages.

Clockwise, from main: the piping over the wings proved to be a headache; cheeky front – nose was painted first as a test; cockpit can best be described as Spartan. From top: demonstrating the compact dimensions; neat ‘quarterlight’; immaculate powerplant; original orange vs modern topcoat; snakeskin trim was sourced in Germany. Clockwise, from main: the opening roof section was a nightmare to get right; neat Hella sidelight unit; excellent visiblity – direct steering makes the KR200 incredibly responsive.