How a team of restorers battled to save a worn-out Ferrari 250

When this glamorous GTE was consigned to an auction sale in 2012, the going rate for a rough but running example was £60k, according to contemporary price guides. But such things can only be updated when cars change hands, and the Ferrari market was charging upwards at a rate of knots. So when an auctioneer suggested to Linton Connell that this former doctor’s car might fetch bids of £90k, even with a seized engine and no tax disc since 1976, it caused a sharp intake of breath.

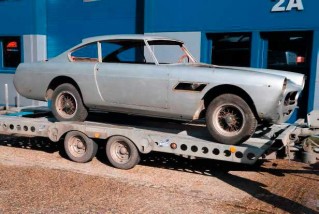

‘It didn’t quite put me of,’ says Linton. ‘I fancied an Aston DB4 but they were always out of budget. And the Ferrari might be a nicer car on the road, with that lovely engine and overdrive gearbox. So I went for it.’ Shortly afterwards the car was trailered to Linton’s home, with rope across the cabin to keep the exhaust on. After 35 years in storage the extent of the work required was becoming obvious. Just to complicate matters, a house move took the Connell family from the Midlands to the south coast, but at least this meant it was easier to attend an open day at Emblem Sports Cars in Poole, suggested by a friend.

‘They seemed like really nice people,’ says Linton. ‘Like me, they enjoy dragging things back to life – I did barn conversions in the Eighties and I knew what was in store. Well… mostly. When the guys at Emblem stripped the car they deduced it was of the road because the previous owner had driven it into the ground. The exhaust fell of, the ignition could barely make a spark, the clutch was down to the rivets and the crank was cracked… never buy a doctor’s car!’

That’s a sentiment with which Tim Bate and Myles Aldous would now agree. They’re the directors at Emblem Sports Cars, and unusually for people with that role they also do much of the hands-on work. They agreed to take on the restoration, looking after the stripdown and assessment, the mechanical and electrical repairs and the re-assembly, while using their regular partners Andy Mitchell and Kevin Baggs for body repairs and trim respectively.

As the stripdown began, Linton dug further into the car’s history. It had been registered new in Rome in 1961 and a few years later was loaned to the film producer Dino Di Laurentiis, then yet to hit the big time but later responsible for such hits as Barbarella, Death Wish, Flash Gordon and Conan the Barbarian.

In 1965 this 250 GTE was inherited by a lady in London with a Park Lane address. She sold it a year later to her doctor, who seems to have used it on a regular basis for the next ten years. Indeed, when Linton got it home it still had the ‘doctor on call’ sticker in the window and other signs of use as a daily hack including crisp packets under the seats.

‘We didn’t find any evidence of a major failure,’ says Emblem’s Tim Bate. ‘What we did find was plenty of indications that it hadn’t been maintained well. It had a repaint in silver at some point – the original colour was Blue Sera – but the more we looked, the more it seemed like the car had been run on a shoestring.’

The stripdown begins – how much corrosion?

When the car was laid up in 1976 a tatty 250 GTE would barely have fetched £1000, while the cost of service items and larger parts would have been as alarming as for a new 365 GT4. So as the slipping clutch and worn, maladjusted distributors made it harder and harder to use, the car was garaged, presumably with an eye to fixing it properly at a later date. That date never came for the owner in question, but his long-term storage did the car some favours. Despite the missing undertray and heat shields that Tim discovered during the stripdown, it was substantially complete and retained its original engine. That was one of dozens of components found to bear the car’s number, including the bonnet and even the parcel shelf. Yes, there was some corrosion to deal with, but Linton’s car was turning out to be an honest, unmessed-with example.

But how much corrosion? That was the news Linton and the team at Emblem were keen to discover when the bodyshell went to Andy Mitchell. ‘First we had it stripped with a gentle blast of glass beads,’ says Andy.

‘That left us with a lot of daylight coming through the floors – they were the worst area. But it was going to need one new rear quarter as well as some work to the sills, plus some tricky repairs to edges and around the headlamp bowls, the back of the wheelarches, the front valance and so on.’

Bodywork and preservation

Few of-the-shelf panels are available for hand-built exotics, but even if complete new sections could be obtained that’s not the route Andy wanted to take. ‘The emphasis is on preservation,’ he says. ‘If you don’t need to cut out an area of original metal, why would you? So we removed only the areas that had corroded away and let in custom-made repair sections in such a way that you’d never see the join.’

Re-making the door skins would probably have been the quickest and most cost-effective way forward, but Andy preferred to unwrap the skins from the door frame and replace the edges with new steel before re-wrapping the frame. Neat TIG welds left a tiny buttwelded seam to dress where the new metal had been used and allowed the car to retain its original doors.

If that seems an involved and costly solution, bear in mind that a pair of genuine secondhand doors in good condition might fetch £10,000 – and they could still require considerable work to achieve a good it in the door apertures. Some areas of damage weren’t touched; the rather obvious hammer marks at the front of the inner wings were created by Pininfarina’s panel beaters in 1961 and remain just as they were.

Mechanicals: ‘The worst we’ve ever seen’

Andy found the kind of deterioration you’d expect on a hand-built Italian car more than 50 years old, but for Tim and Myles the mechanical components seemed to be competing for the title of ‘worst we’ve ever seen’. ‘That was the phrase the carburettor specialist used,’ says Myles. ‘Those Weber 40DCL carbs were terribly corroded and it took a year for them to come back.’ This was a minor headache compared with the engine itself. It was well and truly seized – the aluminium cylinder heads were frozen onto their steel studs.

‘We soaked the whole engine in a drum of parts cleaner over the Christmas and New Year period,’ says Myles. ‘That allowed us to get the cylinder heads started.’

Tim came up with a jig plate that bolted to the head and pressed on the top of the studs, allowing a little more pressure to be wound on each day. Both eventually came of in this manner and turned out to be in decent condition, barely requiring a skim to get the mating face lat. But they also revealed more evil work further down – the head gaskets had leaked water into the bores and the pistons were so stuck they could only be budged with heat and repeated thumping.

Meanwhile, the block, cylinder heads and crank went to Jim Stokes Workshops in Waterlooville, Hants for the engineering work needed before the rebuild. Emblem could have sourced new cylinder liners and pistons from Maranello, but Stokes convinced Tim that JSW could source and supply items that were at least as good, if not better.

That was where the good news ended, though. ‘JSW X-rayed the crankshaft and found it was cracked. A couple of the con-rods were damaged too; it looks like the engine may have had a previous trauma. We had to source a new crankshaft from GTO Engineering in Berkshire.’

Preparation, paint and preventing unfairness

Most of 2015 was swallowed up with mechanical repairs and refurbishment, while the body remained with Andy. He had hand-coated the car with an ICI stabilising compound after bead-blasting, then sanded it of again when every welded repair was finished, after completing a trial it of locks, rubbers, doors and so on to guarantee the metal was where it should be. From there, his highly specific method of achieving a top-notch finish could begin. Etch primer was sprayed onto the bare steel with a two-pack polymer coating to the underside of the shell. U£Pol’s Galvex filler helped with shaping certain contours before a second trial it was undertaken.

‘First we remove “unfairness” with 80-grit paper,’ says Andy. ‘Then a polyester spray filler goes on and gets blocked [sanded] down with 120-grit followed by 180-grit to crisp it up. That millimetre of spray filler is needed to knit everything together; a lot of people miss it out but it’s this that allows every surface to be cut to the same extent. It’s what makes it lat.’ A final trial it completed near obsessive attention to detail before the primer and colour coat were applied. The beautifully-painted shell arrived back with Emblem and trimmer Kevin Baggs assessed the job.

Interior conundrum

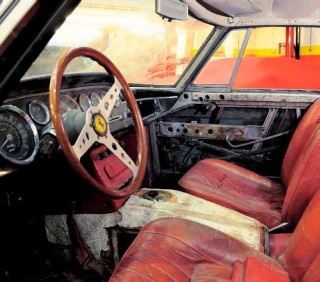

Linton had considered leaving the car’s original trim untouched, but the standard to which the rest of the car was being restored meant a clash with the heavily patinated cabin. ‘It was going to take six hides,’ says Baggs. ‘But the good thing was that we could get the correct leather; it’s called Connolly Vaumol and has a bit of black in the grain, even in tan hides. It’s only recently become available again.’

Kevin put 300 hours into re-finishing the Ferrari’s interior, paying special attention to details such as the padded trim around the bulkhead and transmission tunnel that un-pops for access to the gearbox. The door pockets have a pull-tab that Kevin had to recreate by dragging the top piece of leather over a tiny wooden shape, then embossing and hand-stitching it.

Such a complex and luxurious car was always going to take a long time to put back together. The driveline and body were more or less finished by mid-2016 but it would be summer 2017 before the 250 GTE saw its first MoT in more than 40 years. It wasn’t purely down to assembly time; parts-hunting often added delays, as did decisions to bite the bullet and pay up.

The long, wide search for parts

‘The cost of spares could be eye-watering,’ says Linton. ‘I remember seeing a bill for a tiny bolt with a specific shank length – it was £70. Then there were things like the door handles, which are shared with the 250 SWB… as soon as you say “250”, the price goes mad.’ It wasn’t only fiddly items that needed finding. The back axle had seemingly been run dry for a while – that lack of TLC again – and the differential was beyond re-use. A new crownwheel and pinion took four months to arrive from Ferrari.

‘Tim spent hours looking for parts, and he looked after my money as if it were his own,’ says Linton. ‘There were some things we just couldn’t find at any price, like the rear lights.’

These chromed castings were originally made in Mazac and had suffered the way all pot-metal pieces do, especially in Britain’s salty winters. They were beyond re-chroming but when Tim saw rough secondhand ones were being advertised at £4000 each, he felt there must be another solution. ‘We had the originals digitally scanned, from which a 4K CNC mill – one where both the head and plate can move – machined a fresh one in aluminium. The first ones weren’t usable, but the second-generation attempt was better, and the third-gen is excellent.’

You could build a list as long as a 250 GTE in describing the other efforts the team made to find what was needed. The battery came from the USA – it’s an old-style casing with a modern gel battery inside, while the Marchal air horns are carefully refurbished originals. Borrani wire wheels came from Longstone Tyres in South Yorkshire and the centre slats of the front grille were painstakingly re-made in flat aluminium, adding to a fearsome bill for repairs and re-plating of the chrome trim. The motivation to go the extra mile built up as the standard of the job became apparent to Linton, as he recalls.

‘I hadn’t envisaged replacing things like the grille, but the end result means the decision to spend a bit more each time was justified,’ he says. ‘I can’t expect to make any money out of this, but we could just about afford to make it a really good job.’

What’s surprising and perhaps revealing is that Linton seems a little wistful now that the long and costly restoration process is over.

‘I am, it’s true,’ he admits. ‘I really enjoyed the process and I’m sad to see it finished… I’ve loved coming here once a month and being a part of all this. Emblem have done this job as if it were their own car and I couldn’t ask any more.’

Leather was salvageable but ultimately deemed at odds with pristine exterior.

Former doctor’s car had never had the maintenance it needed.

The GTE returned to its original shade of Blue Sera after a mid-life repaint in silver.

A not-so-graceful arrival with no glazing, door locks or brightwork.

Stripped down and ready for bead-blasting.

Missing undertray led to some corrosion, but it would have been worse if the car wasn’t stored inside.

Prototype rear lights milled in aluminium – the final versions were brass.

They look beautiful now, but those triple Webers took a year of hard work.

Weber 40DCL carburettors were the worst the team had ever seen. Engine extracted ahead of its festive bath in parts cleaner.

Electrical repairs were handled in-house at Emblem.

New pistons and liners were supplied by Jim Stokes workshop.

Owner Linton Connell admits he won’t be profiting from the restoration in monetary terms, but he loved the entire process and felt like part of the team while the work and the search for parts was being carried out.

Low point ‘We had it stripped with a gentle blast of glass beads. That left us with a lot of daylight coming through the floors – they were the worst areas. It was going to need some tricky repairs, too…’

High point ‘When we finally finished the engine rebuild after all the grief involved in stripping it, we ran it for the first time on a stand. Hearing it come back to life was terrific’

MY FAVOURITE TOOL

‘Ferrari’s Colombo V12 engines are very sensitive to precise timing; the two sets of points in each distributor have to be exactly 180 degrees apart and then the second distributor has to be timed to the first one,’ says Tim Bate of Emblem Sports Cars. ‘I like this oldfashioned probe with a lightbulb inside for setting the static timing because unlike an LED, the bulb in this one lickers and gets brighter or darker depending on how close to spot-on you are. They’re harder to get hold of now – I’ve had this one since I was 20 or 21.’