Epic Restoration How James Glickenhaus turned the wildest concept of the Seventies – the Pininfarina Ferrari 512S Modulo – into a working road car. How the Seventies’ greatest concept-car finally hit the road.

EXCLUSIVE Brave rebuild of the greatest ever concept car

Says Hollywood director turned car collector and racing team manager Jim Glickenhaus, ‘Modulo is one of the most iconic Ferrari show cars ever made. I think it’s what cars will be like when they are spaceships. After all, it was very connected to spaceships in its design and aesthetics.

‘I got to know the team at Pininfarina well through my Ferrari P4/5 project and I wanted to buy the Modulo for many years, but Pininfarina wouldn’t sell it to me. I stayed in touch with them and a while after the passing of Andrea Pininfarina in 2008 they started taking a different direction with the museum and I got a call saying, “We think you are the guy to carry Modulo on.”

‘My mechanic Sal and I went to Cambiano to collect the car and once it was loaded in the truck he said to me, “What do we do now?” I wanted it to drive. I don’t have cars in my collection that don’t drive, and Modulo is no exception, so the answer to Sal’s question was to make it drive – properly!

‘Some people think it drove once, but it never ran under its own power. There is a video of it ‘running’ but they just rolled it down a hill and took a video of it. In fact when we pulled it apart, it had no crankshaft, camshafts, pistons, rods or gearbox internals.

‘Unlike most concept cars, Modulo is on an original race car chassis, meaning it has real uprights, real shock absorbers, brakes and the like. It required a lot of fettling, but the structure to make it run was there. ‘The chassis used is Ferrari 512S chassis number 27, which had later been turned into a 612 Can-Am car, chassis number 0864, before it was dispatched to Pininfarina to become a concept car.

‘I asked Sal to take on the project, and we agreed that it made sense to restore the car in Turin, Italy, so that Sal could make best use of his extensive network of contacts and skilled marque specialists in the area, from his time in the Ferrari racing team in the Sixties and Seventies.

The project begins

Says restorer Sal Barone, ‘When Jim and I saw the Modulo in person about ten years ago, Jim said, “It is a beautiful car.” I replied, “I see what you are thinking.” Nothing else needed to be said – we have worked together so long, over 40 years, that we know what the other is thinking. Jim said, “Let’s see if Pininfarina will sell us the car.”

‘Once the deal was done, we relocated the car to Turin and I got into the restoration. I did the car piece by piece; no bolt, not a single one, was left untouched.

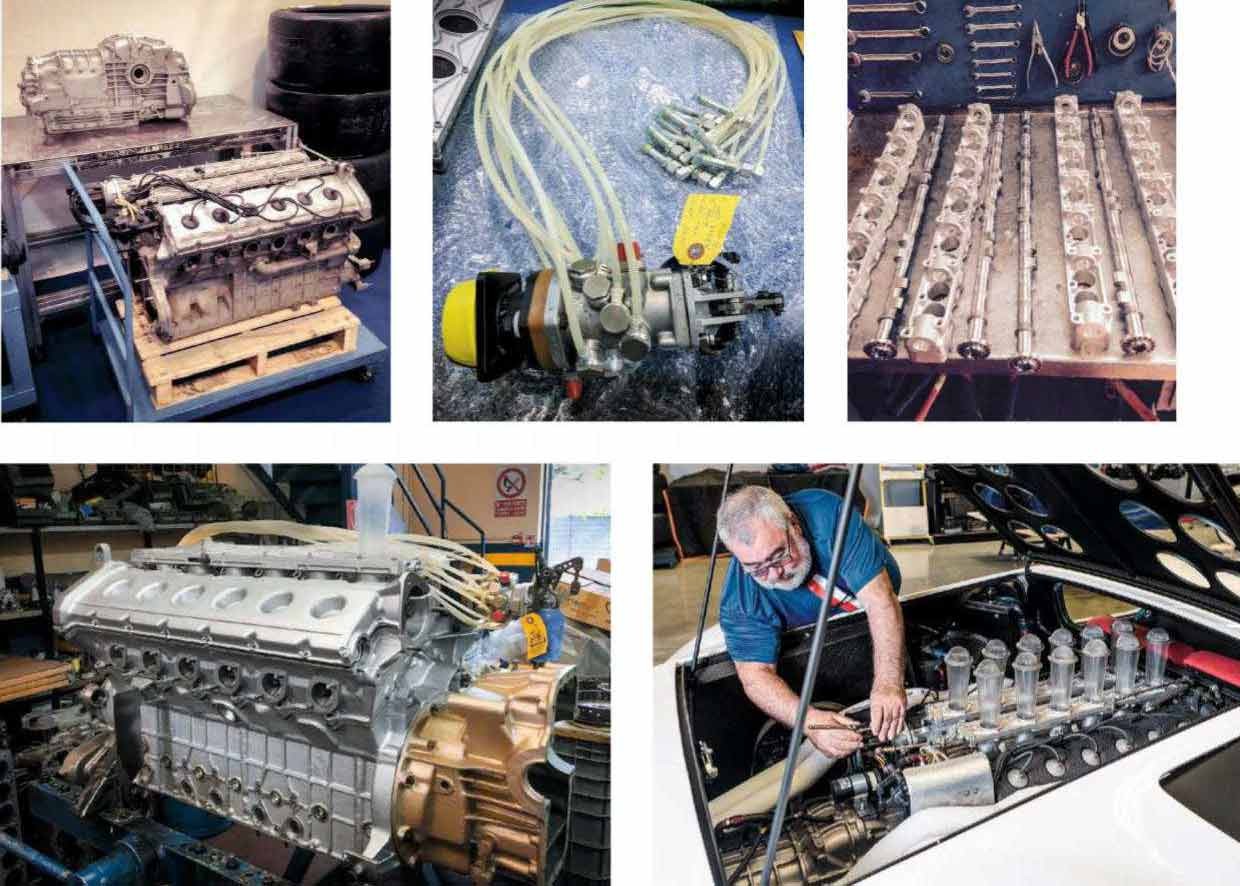

Engine and transmission

Explains Sal, ‘I started by taking the engine and transmission apart and found they were just empty cases – they were there just for the shape, but empty inside. Nothing is available of the shelf for these engines, but luckily I had a friend who has lots of Ferrari parts – he owned two 512Ss in the day and had bought them from other teams. He had everything we needed to fill them!

‘The engine block is the car’s original from its 512S days and is now running in that specification with mechanical fuel injection. ‘Once the parts were sourced the engine went together fairly easily; all the castings were in good shape and so on. The few pieces that were missing, such as the water pump drive, were fabricated from original 512S blueprints. The engine was machined at Sport Auto in Modena and we worked together to assemble it.

‘The car’s injection pump was an incorrect Lucas unit from a Maserati. Fortunately, we had an original 512S unit that came as part of a ton of P racing car spares we had bought in Modena. It was modified by Jim Kinsler from 8mm low to 6mm low. It would be slightly too small for flat-out racing, but the compromise means it meters fuel better for slower speed driving, ideal for Modulo. ‘We don’t have dyno results for the engine, but on the road the engine is great – it is tractable and has lots of torque.’ The engine and transmission took two and a half years to complete.

Suspension and steering

Continues Sal, ‘With the engine and transmission done, I spent a few months working on the suspension and steering. The suspension and brakes are standard Ferrari 512S items. Everything needed going through, but it was all there. I gave the suspension new bearings, the brakes new seals, and rebuilt the pistons and dampers. There was nothing technically tricky about this part of the job.

‘The steering was a bit of a problem though. The front wheels hit the bodywork when any substantial amount of lock was applied. The steering rack was too long to work properly so we replaced it with a shorter P4 one. We also made new wheels, replicated from one of our racing cars to give a little more clearance. With all these changes we were able to get an acceptable amount of steering lock. It now has roughly the same amount of lock as a Ferrari racing car of the day – it’s drivable even in tight traffic. The steering is still very direct, with only one and a quarter turns lock to lock.

‘For safety we replicated original 512S/P4 uprights in alloy because magnesium after 40 years is unsafe – it’s weakened by corrosion and is subject to burning should anything go wrong. The P4 and 512S suspension castings are exactly the same in design, just machined differently. Ferrari did this a lot to save money. ‘At the rear the wheels were also touching the bodywork.

Again, we made new wheels, and that combined with removing the spacers and machining some material of the uprights gave us enough clearance. Eventually I’d like to make another set of wheels that are a little wider and ill the guards out a bit more.’

Chassis

‘With the suspension and driveline done, we trial-assembled the car. I was so excited for Jim, but when he jumped in we quickly discovered he didn’t it – there was absolutely no way he was going to be able to drive it the way it was. I thought “Oh dear, this is going to be a bit of a problem to fix…”

‘I set about making alterations so Jim could drive the car. We lowered the floor pan by one to two inches – lowering the seat with it – then moved the pedals forward two inches and shortened the steering column. We also took the opportunity to shift the steering wheel to match the centreline of the seat because it was offset to one side of the driver before.

‘We did this by making U-shaped sections that slipped over the existing chassis rails and were welded at the tube centreline. This allowed us to lower the floor pan without changing any of the chassis geometry, and we made it such that we could remove all the new pieces and leave the original chassis as it was.’ Once Sal had installed all the new metal, the chassis was stripped back to bare metal and repainted. ‘It was at about this point that we got distracted by other cars and projects.’

One of those projects was developing the SCG003 sports-racer for its annual assault on the Nürburgring 24 Hour race. ‘Modulo dragged along with little bits getting done here and there between other jobs, but it wasn’t going anywhere in a hurry. Finally we made a decision that it really needed to get done, and to focus on it and get it finished. I set a date and got stuck into the work. The date was June 30, 2018 – it had to run by then, no excuses.

‘I arranged for some people to give me a hand and I went to Italy and worked on it fulltime from October 2017. I spent more time in Italy than at home for the next few months. By this time we had started getting some press, and while lots of people loved what we were doing, others didn’t. During one of my many trips, on a light from Milan to Sicily, I was accosted by a fellow telling me, “You are ruining something that made Italy proud, what you guys are doing is wrong.”

‘I explained to him that Jim will get the car out into the world for everyone to see, and that’s much better than sitting in a museum where few would see it. I also explained that we’ve not done anything that can’t be reversed easily, but he remained unconvinced.’

Mechanical finishing

‘Modulo had never had a cooling system, so we created one from scratch,’ says Sal. ‘All the way along we focused on doing things to make the car genuinely driveable. An interesting example is that there are laps on the side of the car to feed air into the radiators, but they were never operable. So we’ve motorized them so that when the engine gets warm in traffic, they can be opened. We also added a manual switch on the fans in preparation for traffic duties.

Body

The body was in great shape, with no damage or corrosion issues. All we did was reinforce it around the mounting points on the rear to strengthen it enough for driving.

‘Although we were always very careful with the body – it spent lots of time with protective blankets taped over it – inevitably it picked up some scratches during the restoration. We made the tough call to sand it back and give it a fresh coat of Modulo Pearl White.’

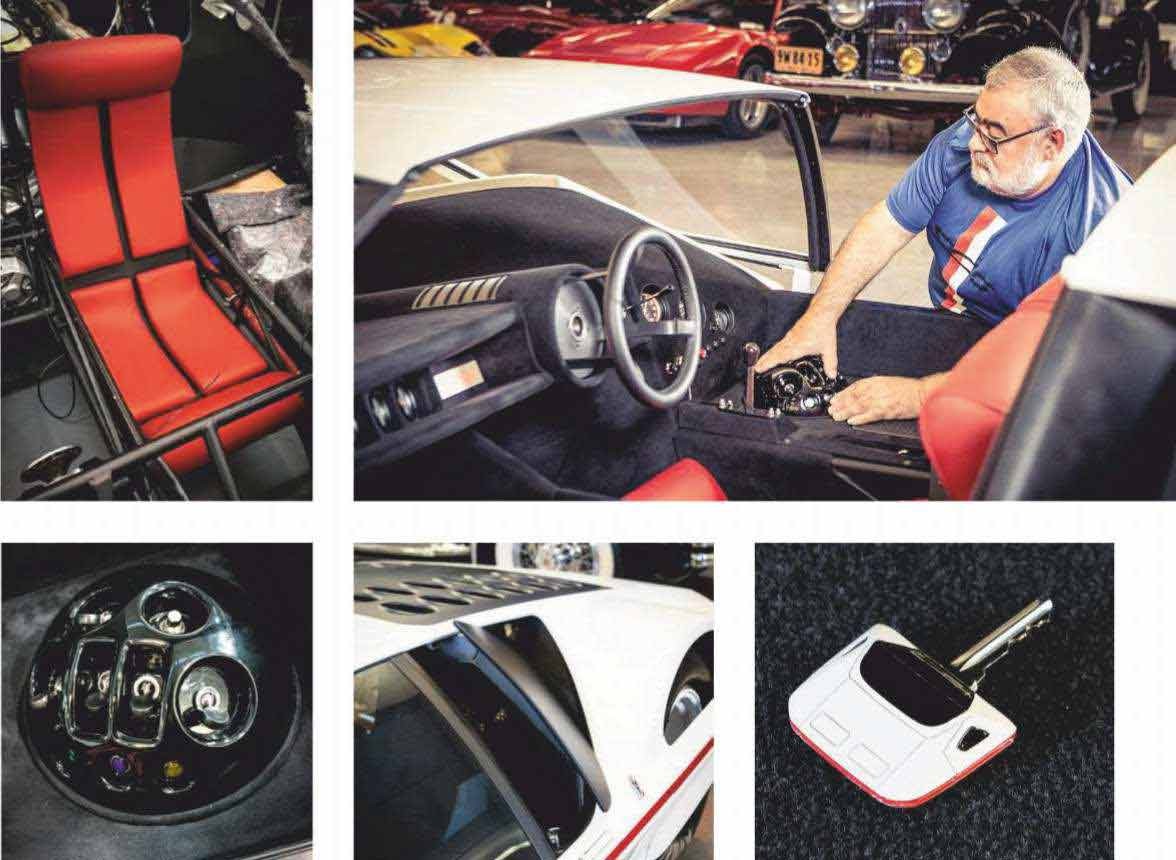

Interior

‘We didn’t change much with interior,’ says Sal. ‘We just gave the seats new padding and trimmed them with new-old-stock leather. ‘One of the more difficult aspects of the interior was packaging all the controls in the control ball – it actually can be rotated or adjusted, so everything has to it inside nicely for that to work properly. The problem we had was that we needed additional control for the things we added to make the car driveable, such as the now-powered air intake laps. I didn’t want to add extra switchgear but there weren’t any spare spots in the ball, and adding anything to the dash would take away from the clean aesthetic. To solve this problem we used multi-function switches – with additional positions and actions, it gave us more functionality with the same number of control switches.

‘Modulo never had a key, and I wanted to create something special for Jim. We 3D-scanned the entire car to get the data for the outside dimensions and shape, then 3D-printed the key to match.’

First drive and finishing

‘Having worked on the car full-time from October 2017, it was finally time to start the engine. On June 15th, 2018, Modulo moved under its own power for the first time. Its first drive was around the streets of Turin with the canopy of. When it was time to head out of the workshop I couldn’t believe what we were about to do. The first thing I thought was, ‘Oh shit, it’s really moving!’ I started to shake and I cried. Then, as we got into the drive, I was just so happy that everything was going well – there were no leaks, and it steered left to right just the way it was supposed to. We were very careful, but overall it couldn’t have gone any better.’

‘When we first got it running it was very loud, so we created a custom muler system that tucks in the back of the body. Like everything else we’ve done, it’s in line with the car’s design and can be completely reversed if necessary.

‘I am so proud to have done this car. I spent lots of time far away from my family to do it, but the result has been worth it. At the moment almost nobody knows Modulo. I’m so happy that we can bring it out so people will see the beauty of the car. Jim makes sure every car he has gets shown to the public. I’ve never seen another guy who is so proud to share what he has with other people. If there are kids in the street near the workshop and the door goes up, Jim invites them in.’

‘The car was only driven twice before Pebble Beach – that time in Turin, then Jim drove it around the block near our New York workshop. In fact, I talked him out of taking it for a run on 17-Mile Drive before the Pebble Beach show. I would normally be in favour of it, but because the car was not shaken down I didn’t want any teething issues to show up before the Pebble Beach Concours.

The moment of truth

Says Jim Glickenhaus, ‘The Pebble Beach Concours was where we first showed Modulo to the public. I was very pleased to be able to drive it down onto the field. Once we got parked there was much discussion between the judges about how they were going to be able to judge it, because it never ran originally. It is such an amazing car, how the hell are you going to judge Modulo? It’s like judging Michelangelo’s David or the Mona Lisa. In the end we were awarded the Most Elegant Sports Car award, which was great.

‘We have a few things to sort out, for example the alternator gave us trouble at Pebble Beach. It is a 50-amp unit, but it only makes any decent current at high rpm, so I was pretty much just driving on the battery. In fact, I had to get a push and jump-start it of the ramp after receiving the award. Sal knew of a barn in the middle of the US filled with old racing car parts, and thought he remembered seeing an original 512S alternator there years ago. The barn owner wasn’t sure, so Sal drove halfway across the country to look for himself. He came back with two new-old-stock alternators that can now be rewound to work at a low rpm. ‘Now that it is finished I plan to drive it and enjoy it, like I do with all my cars.’

Low point

‘With the suspension and driveline done, we trial-assembled the car. Jim got in but we found he didn’t fit – there was no way he was going to be able to drive it’ Sal Barone

High point

‘The first trial drive was around the streets of Turin, with the canopy of. I cried, and started to shake – after four years I was so happy that everything was going well’ Sal Barone

MY FAVOURITE TOOL

Sal Barone’s TIG Welder

‘My TIG Welder is my favourite tool,’ says Sal. ‘While it’s not the original way to weld on a car like Modulo, the fine control and the quality of weld it gives just can’t be matched with a traditional ARC Welder. ‘You won’t see much of the work I did on Modulo with it because it’s all hidden on the chassis, but it helped me create many beautiful strong welds.’

By the time Jim and Sal collected the Modulo from the Pininfarina museum in 2014, Jim’s vision for it was already set in stone…

Modulo moved from the Cambiano museum to Turin for the work before going to the US for Pebble Beach.

Sport Auto machined new camshafts Rebuilding the V12 was refreshingly straight-forward V12 was rebuilt to its original 512S spec, albeit with a modified mechanical fuel injection system Sal’s local contacts were vital for sourcing rare parts Engine block inherited from Modulo’s past life as a sports prototype.

Sal retained the original brakes but gave them new seals.

Sal had to source all the missing internals for the V12 engine case… …before installing it in the 512S’s spaceframe with a new fuel injection system.

The Modulo threw up unique challenges that restorers don’t usually face. Original seats were retrimmed with NOS leather Steering column had to be shortened …like the newly-motorised cooling flaps

Key was made from a 3D scan of the car, then 3D printed Multifunction switches allowed new features.

Canopy was removed until after the first test-drive.

Reversible chassis changes allowed the floor to be lowered New wheels alterated for better body clearance Mulers were custom-made to stile the noise Canopy was removed until after the first test-drive It’s a wind-up. Black knob raises and lowers headlights.

Original seats were retrimmed with NOS leather Steering column had to be shortened.

Despite competing for attention with the SCG003, the Modulo received a scratch-built muffler system.

It took four years and some serious ingenuity, but the Glickenhaus team successfully turned one of the most striking concept cars ever made into a running, driving reality.

Shortened steering column one of several changes to make it driveable. Well, to be road-legal it needs a numberplate….