McLaren F1 It’s 25 years since the F1 became the world’s fastest naturally aspirated car. We take one to the track to discover why nothing has managed to surpass it. We break the 200MPH barrier in a 2765-mile McLaren F1. Back in 1992 the 240mph McLaren F1 became the fastest naturally aspirated road car ever made. 25 years on, it still hasn’t been surpassed. We unleash the mighty V12 on track to find out why. Words Ivan Ostroff. Photography Glenn Lindberg.

F1 Champion

There’s a distinct tremor to the hand I reach out to open the F1’s nearside door. The wide aperture seems to promise easy access but actually getting into the central driver’s seat involves slithering inelegantly over one of the two flanking passenger seats, backside first. If there’s one thing you cannot do with a McLaren F1, it’s get behind the wheel with any dignity.

No wings needed on F1 – fan-assisted ground-effect underside design provides most of the downforce.

My nerves settle a little as I get myself comfortable in car 069 – the 60th of 64 road cars built. Certainly it’s all very unthreatening at first acquaintance – F1 passengers sit slightly behind the driver so the field of vision is largely unrestricted through 180 degrees. There are no airbags of course but I’m strapped tightly into into a four-point harness and cocooned by a strong carbon-fibre tub whose design owes its origins to Formula One technology. The driver’s seat can accommodate anyone over six feet tall so there’s a remarkable feeling of spaciousness, the race-style pedals are dead ahead and my hands fall naturally on the leather-rimmed three-spoke steering wheel and the gearlever to my right. Some driver information is dealt with by an LCD display but the black-on-white dials are clearly visible through the wheel – large rev counter dead ahead, 240mph speedometer to the right and fuel and oil/water temperature in a cluster to the left.

I twist the key and engage the starter motor. There is a metallic clatter as it connects with the ring gear then six litres of highly tuned V12 bursts into life. I expect the clutch to be heavy and rather binary – either fully in or fully out with nothing in between – but it’s actually surprisingly progressive.

Shifting into first gear reveals a fluid and smooth action, although the stick travel is longer than I expected. Pulling away, I listen to the gentle rumble of the mighty engine behind me then shift into second. I slowly climb up through the gears and eventually slot into sixth, at which point I floor the throttle. The exhaust note instantly switches from a gentle purr to a full blown roaring growl and the McLaren pulls from just 2000rpm in top gear – about 60mph.

24-carat gold foil deemed the best material to reflect vast engine bay temperatures. Rev counter dominates instrument panel – for once, the speedometer doesn’t flatter to deceive. Central driving position gives unparalleled view through the electrically heated and solarinsulated windscreen.

With 480lb ft of torque on tap I could probably skip gears in traffic without diminishing the sense of throttle response immediacy or colossal acceleration. The unassisted steering, so heavy at low speeds, comes alive the faster I go. Get it up to thoroughly illegal speeds and it’s frankly perfect. There are just 2.8 turns from lock to lock, so it’s wonderfully direct and sitting in the centre of the car makes me feel like I could point and squirt the F1 in any direction with millimetric precision. Let’s find out.

Back into first gear. I let the rev counter hit 3000rpm then drop the clutch. As I floor the throttle the response is shockingly quick. The V12 thunders and the rev counter needle storms further around the dial. Initial wheelspin is gradually countered by the F1’s astonishing traction and my chest soon feels like it’s being compressed by giant invisible hands. I don’t even have time to glance at the speedometer – my torso is still being shoved back by the G-forces – so I grab second gear. The engine delivers a deep, visceral growl at 7000rpm as 48 valves thrash away – I have never heard anything quite like this. It’s utterly mesmerising.

The F1 is still accelerating hard but I’m too preoccupied with the rev counter to notice where the speedo needle is pointing. I know that 60mph came up in 3.2 seconds while I was still in first gear and I know too that it passed 100mph just 3.1 seconds later while I was still in second. I’m in fourth gear now and the McLaren is still accelerating like a rocket. There’s simply no let-up through fifth or sixth at around 155mph and it’s steady – and still accelerating – at 200mph. It’s a good thing we’re on a test track.

Then I remember that test tracks have corners and sure enough I’m bearing down on a fast left-hander. I shuffle my right foot across to the brake pedal and stand on it. The F1 has no ABS but the massive ventilated discs and four-pot calipers provide firm and controlled braking without any nannyish electronic aids spoiling the fun. Period critics said the F1 should have had a servo-assisted braking system, but I disagree.

F1’s first owner had it repainted from Mercedes Silver to Anthracite shortly after buying it. Ball-jointed dihedral doors open no wider than ordinary doors.

I drop down a gear ahead of the next corner and heel and toe for the hell of it, revelling in the music. The F1 excels in these fast, sweeping bends; quick changes of direction don’t even come close to upsetting its balance – in fact it seems to grip harder the faster I go, the chassis and suspension complementing each other perfectly.

The ride is firm but surprisingly comfortable thanks to special bushes that allow longitudinal suspension movement without affecting lateral stability. It looks like there’s a certain amount of body roll from outside the car but the driver, sitting centrally within the roll centre, isn’t really aware of it. In fact the F1 is set up in such a way that I already feel confident about driving it hard. It understeers initially at relatively low speeds but a blast of the throttle soon kicks the tail out. Then a flick of the wheel later I’m in a $12m power slide and having the sort of fun I last enjoyed in a Caterham 7.

Strangely the F1 doesn’t feel quite as planted on long stretches of flat tarmac road as it does when I’m flicking left and right through fast corners. There, it is in its element and the only period rival that can come anywhere near it is the Jaguar XJ220. But the McLaren betters it on two counts – it’s quite a bit smaller and its normally aspirated V12 is more predictable than the Jaguar’s twin-turbo V6. The F1’s tail can get a little skittish on wet roads but there is no turbo lag – the BMW power unit does what you want, exactly when you want. Treat the McLaren with the respect and it won’t bite you.

But don’t go thinking that this is just a track-only hardcore supercar; in fact I’d be perfectly happy to drive it over very long distances. Gordon Murray designed the F1 in such a way that it can accommodate a full set of bespoke luggage within body cavities behind the doors and there’s even a golf bag designed specifically to fit onto the front passenger seat. The big BMW V12 won’t fluff or complain if you drive it at sensible speeds on country roads and the six-speed gearbox makes refined highspeed cruising perfectly possible. If there’s a problem with driving an F1 in this manner it’s that there’s always a devil on your shoulder goading you back into hooligan mode. It was in 1988 that Gordon Murray and Ron Dennis first discussed the idea of building a McLaren road car that would outperform all other supercars in terms of speed, technology, and engineering quality.

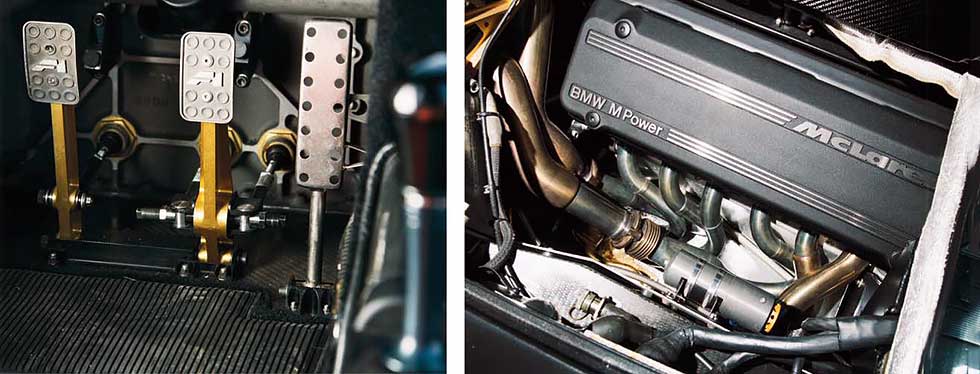

Race-inspired adjustable floor-mounted pedal box – brakes are unservoed. Quad-cam BMW S70 V12 delivers its maximum 627bhp at a screaming 7400rpm.

Murray’s world-beating F1 expertise and uncompromising approach resulted in a technological tour de force. When the F1 was announced its carbon-fibre chassis drew on the latest Formula One technology and gave it immense strength. The gearbox was mounted transversely, allowing the differential to sit alongside the clutch, which in turn helped to keep the weight down and the car shorter. Speaking of weight-saving measures, the F1’s wheels – like its camshaft cover – were made from magnesium and the wishbones machined from solid aluminium. Kenwood even designed a new lightweight CD player for it.

The specially developed BMW V12 had dry-sump lubrication and endowed the F1 with the highest power-to-weight ratio of any previous production car at that time. The gold reflective foil lining the engine compartment wasn’t just for show, either – it was deemed to be the most efficient material to deal with the colossal heat buildup generated within the engine compartment. It’s rumoured that each car needed eight ounces of the stuff.

Each F1 also took around 15 weeks to build and all customer cars were equipped with modem sockets so the factory could diagnose problems remotely via the internet – a feature that helps McLaren Special Operations to maintain F1s to this day. Our car looks very different from how it would have appeared when new. It was originally Mercedes Silver but its first owner had it fitted with a High Down Force/LM kit and repainted Anthracite shortly after buying it. It spent seven years in the US before returning to the UK and having its wheels painted black. A subsequent owner removed the LM kit and returned the wheels to silver but they were painted black again seven years ago.

The F1 was designed to be a road car but race versions enjoyed considerable track success, including winning the Le Mans 24 Hours in 1995. Three years later an F1 hit 242.8mph, smashing the the record for the world’s fastest production car.

The McLaren F1 set new supercar performance parameters at its launch in 1992 that still hold up well today. Priced at £540,000, it had to compete with the likes of the £400,000 Jaguar XJ220, £240,000 Bugatti EB110 and £163,000 Ferrari F40. The wild-looking F40 may be monstrously powerful but it’s also so big and wide that it’s something of a liability on public roads. The Bugatti is little better than the F40 in this respect and no low-volume Italian supercar was ever going to be able to match the sort of reliability offered by a factory-supported F1. As for the XJ220, John Nielsen – one of the drivers who raced an XJ220C at Le Mans in 1993 – once said that it was simply a most aesthetically pleasing sculpture. It may be great to drive but its turbo-charged Metro 6R4-derived V6 sounds like a tin of old nails compared to the F1’s howling V12.

The Bugatti Veyron may have ultimately bettered the F1’s top speed, but it needed four turbochargers to do it; tellingly the F1 remains the fastest normally-aspirated production road car ever built. It’s rarer too – production ended in 1998 after just 64 road cars had been made.

In short, the McLaren F1 is still the epitome of a true driver’s car and almost certainly the greatest road car ever made.

Thanks to: Dean Lanzante at Lanzante Motorsport, [email protected]

I DESIGNED IT: GORDON MURRAY

Gordon Murray conceived and designed the McLaren F1 with Peter Stevens penning the exterior and interior. Murray wanted to create a car with new levels of performance and handling but also a degree of practicality.

Murray was born in Durban, South Africa in 1951. ‘My dad was a mechanic – I remember at six years old being taken to race meetings and watching him help his friends to build their racing cars. It got in my blood and I wanted to be a race driver. However, I didn’t know I would grow up to be 6ft 4in tall and 14 stone!

‘I spent 17 years at Brabham before Ron Dennis convinced me to join McLaren. I designed three cars in my three years there and we won three world championships.

‘Ben Scott-Geddes was there almost from the beginning with the F1, and Graham Halstead joined us when we were doing the GTRs. The road car came first, then the GTR, with which we won at Le Mans in 1995, as well as winning the Global BPR Endurance Championship.’

TECHNICAL DATA 1998 McLaren F1

Engine 6064cc V12 BMW S70/2, dohc per bank, four valves per cylinder, Lucas multi-point fuel-injection, TAG EMS engine management system

Power 627bhp @ 7400rpm

Torque 480lb ft@ 5600rpm

Transmission Six-speed manual, limited-slip differential, rear-wheel drive

Steering Rack-and-pinion

Suspension Front and rear double aluminium-alloy wishbones, coilover dampers, antiroll bar

Brakes Ventilated and cross-drilled discs and four-piston calipers all round

Weight 1138kg (2509lb)

Performance Top speed: 240mph; 0-60mph: 3.2 sec

Price new: £540,000.

Current values £7m-£9.5m

“The exhaust note instantly switches from gentle purr to full-bore roaring growl”