The XJ 220 and F-Type SV Rare Jaguar’s only 200mph supercars, so to celebrate the XJ220’s 25th Anniversary we drive these two monsters back-to-back. Words by Paul Walton. Photography by Antony Fraser.

FIGHT CLUB F-TYPE SVR Vs JAGUAR’S TWO 200MPH SUPERCARS GO HEAD-TO-HEAD / XJ220 VS F-TYPE SVR Jaguar has just two genuine 200mph production supercars: the XJ220 and the F-TYPE SVR. To celebrate 25 years since the former entered production, we compare these two incredible cars back-to-back…

When Jaguar revealed the F-Type SVR in 2016 it joined the exclusive 200mph club. Membership of this exclusive club is restricted to manufacturers with a production car that can reach the magic double ton, so those eligible are few and far between. For Jaguar, though, this is the second time.

The XJ220 from 1992 was Jaguar’s first to reach 200mph and, for a short period in the Nineties, was the world’s fastest production car.

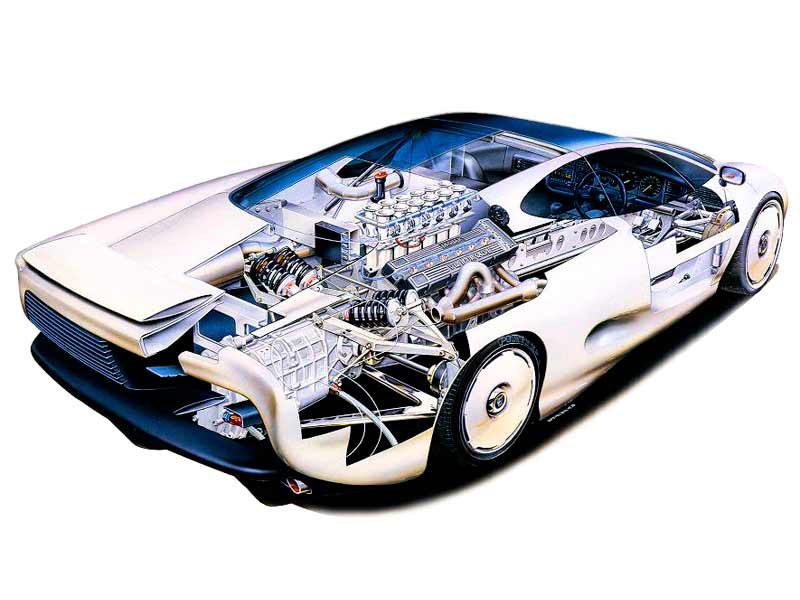

Even though both cars top 200mph, they arrive there via very different methods: one is a low-volume, mid-engined, purpose-built supercar with a turbo-charged V6, while the other is front-engined, powered by a supercharged V8, and based on a mass-produced sports car. To compare these two ways of achieving 200mph, we drive these fabulous cars back-to-back.

The XJ220 was a car that shouldn’t have been. Conceived by Jaguar’s chief engineer, Jim Randle, as the British company’s entry into Group B racing, it was a behind-the-scenes project, and not part of the company’s official product planning.

Having designed a chassis and built a mock-up from cardboard, Randle persuaded several engineers and designer Keith Helfet to develop the supercar in their own time. The team was known as the Saturday Morning Club (the name given to any of Jim’s behind-the-scenes work) and Jaguar’s management knew nothing about what they were up to. Even Jaguar’s company chairman, Sir John Egan, didn’t see the car until a week before it made its debut at the 1988 British Motor Show.

The response it received when unveiled was incredible. Crowds around Jaguar’s stand were several deep and 40 people put down deposits on the first morning of the show. But that was understandable. Not only was it low, sleek and unlike the traditional saloons and GTs the company was famous for, but the prototype had a 6.2-litre version of Jaguar’s V12 and four-wheel drive, making it as fast as it looked.

Due to the positive response, it didn’t take long for Jaguar’s board to decide to put the car into production. However, with the Browns Lane plant already at full capacity with XJ6 and XJ-S production, who would build it? Step forward Tom Walkinshaw of TWR: no stranger to working with Jaguar after running the company’s racing team since the early Eighties – in both European touring and then international sport cars – TWR was also producing low-volume, sportier versions of Jaguar’s existing range under the Jaguar Sport name, a separate company owned jointly by both parties.

With an agreement in place, a new company – XJ220 Ltd – owned 100 percent by Jaguar Sport was set up to build the new car. Coventry-based coachbuilder Abbey Panels would construct the aluminium body before the shells were completed at a new factory at Bloxham, 25 miles north of Oxford, which was officially opened by HRH Princess Diana in October 1991.

Since the concept was heavy, complicated and expensive to build, the eventual production car was not exactly the same as the show car. Four-wheel drive had been abandoned for rear-wheel drive but, most controversial of all, the V12 was swapped for a turbocharged V6. There were two reasons for these changes. Firstly, weight: the Ferrari F40, for example, with its 2.8-litre twin-turbo V8, was considerably lighter than the original XJ220 concept. Secondly, there was the cost: instead of choosing the expensive-to-build V12, TWR decided on a smaller V6 that it already owned the rights to, which had an interesting story itself.

Starting life as General Motors’ lightweight aluminium V8 in 1960, it was originally licensed to Rover for use in its P5 saloon, but became the mainstay for British car manufacturers and stayed in production until the mid-2000s. In the Eighties, Dave Wood, from Austin Rover, extensively modified the V8 for the Williams F1-designed Metro 6R4 rally car by lopping off two cylinders to create a 90-degree 3.0-litre V6. More was to come. In the late Eighties, changes in Group C sports car rules meant TWR had to swap its existing 7.0 V12 for a smaller unit, so it bought the rights to the V6 and increased the capacity to 3.5 litres. With 800bhp, it became a race winner in sports cars on both sides of the Atlantic. A pedigree like that meant it was perfect for the XJ220. Sadly, though, it wasn’t that simple.

Although Keith Helfet had been seconded to Bloxham to redesign his car for production, keeping it as close to his original as Walkinshaw would allow, when car 008 was unveiled at the 1991 Tokyo Motor Show, there was criticism that it was to a different specification than the 1988 concept.

Anyway, that was to miss the point. Long, low and with perfect proportions, it was arguably prettier than any of its supercar rivals – including the Ferrari F40 and Porsche 959 – and, V6 or not, it was devastatingly fast.

With the turbo-charged 3.5-litre engine producing 542bhp and the car weighing just 1,470kg, it could reach 60mph in less than four seconds and had a top speed of more than 200mph. This was confirmed in 1992 when Jaguar’s 1988 Sportscar champion, Martin Brundle, reached 217.1mph at the Nardo test track in Italy. This result singled it out as the fastest production car in the world, a record that lasted until 1998 when the Mclaren F1 reached 240mph.

Production started in April 1992, and Jaguar announced that the first customers could take delivery of their cars in June and July that year, and that a total of 350 XJ220s would be built.

But a different specification wasn’t the only problem facing the car. On 16 September 1992, just months after production of the XJ220 started, the British Government was forced to withdraw from the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) after it was unable to keep the currency above its agreed lower limit. Known as Black Wednesday, it saw interest rates soaring and plunged the UK into a long recession. As the price of car was £450,000, Jaguar suddenly faced around 75 of its would-be customers defaulting on their contracts, refusing to take delivery of their car and even sacrificing their deposit rather than pay the full retail price. Although the courts ruled in Jaguar’s favour, the company remained stuck with too many unsold cars. Production eventually ceased in mid-1994 with just 274 production cars built, and, left with several unsold XJ220s, Jaguar offered heavy discounts on this. Apparently, the last of these unsold 200mph supercars was sold in 1997 for £127,550.

Maybe it was due to the marked difference between the reality of the car’s specification to the concept or because of its complicated birth and mixed parentage, but by the 2000s the XJ220 was the forgotten supercar of the Nineties. While the Ferrari F40 and Porsche 959 became collectable, their values growing accordingly, the XJ220 was at best ignored, at worst derided.

But that situation is slowly starting to turn around as Keith Helfet’s beautiful design becomes appreciated and the non-Jaguar V6 no longer such a big problem. While as recently as 2014 an XJ220 could be bought for less than £200k, you’re now looking at over £450,000. And the wider classic car market is welcoming the car: after years of owners not being able to buy new tyres in the correct size, both Pirelli and Bridgestone [see box out] now offer rubber designed specifically for the car, and along with Don LawRacing, which has specialised in these cars for years, Jaguar Land Rover’s Classic Works now has an area in its new facility in Ryton reserved for servicing and maintaining 220s where owners can get support.

It may have taken 25 years, but the XJ220’s moment has finally arrived. But now it has a younger, more modern, relative: the F-TYPE SVR.

Part 2 TWIN TEST XJ220 vs F-TYPE SVR

In almost 20 years of messing around with cars for a living I’ve never seen anything quite as amazing as this XJ220 and F-TYPE SVR together: two different styles of cars, both beautiful and dramatic.

As a purpose-built supercar from the outset, its designer – Keith Helfet – didn’t need to make the same compromises over boot and interior space as he would have had to with a mainstream sports car.

The resulting very low and very sleek shape always reminds me of a UFO, especially as, it being mid-engined, the nose is very short like a Group C racer’s of the Eighties and Nineties. Unlike the dated, more angular 959 and F40, it too has curves similar to the X100 XK8 and remains one of the most beautiful cars of all time. And I love the way a Perspex hatch shows the engine – a little piece of automotive theatre. Sadly, some of the detailing, such as the rear light clusters that come from the Rover 200, looks a little cheap and out of place on such a purebred. Even though the 200mph SVR was developed by Jaguar’s Special Vehicle Operations and costs over £110k, it does not have the certain something that makes the XJ220 so special, because the F-TYPE is still based on a mass-produced, front-engined sports car. If the XJ220 were a UFO, then the SVR would be an off-the-shelf jet fighter.

The F-TYPE Coupé still remains one of Jaguar’s prettiest cars, even though its shape isn’t as pure as the 220’s, but the difference is in the SVR’s over- the-top aero aids. Whereas clever aerodynamics turn the XJ220’s body into one big wing that pushes the car down at high speeds so that it needs nothing other than a discreet rear spoiler, Jaguar has given the F-TYPE an extreme aero package. While these additions do make it even more of a head-turner, the big wing and wider front bumper make it less attractive than the XJ220, or even its own smaller-engined siblings.

The XJ220 featured here has had an interesting life. Chassis 004 was one of ten preproduction cars built between March and April 1991. Used for chassis development and transmission testing, it clocked up 100,000 testing miles and was the first to hit 200mph in the hands of 1988 Le Mans winner Andy Wallace. After its career in GT racing, in which it was never crashed or seriously damaged, the car was converted back to road specification.

“Long, low and with perfect proportions, it was arguably prettier than any of its supercar rivals”

Still wearing the lattice-style wheels of the prototypes, rather than the handsome Speedline Corse-designed alloys of the production cars, it’s in an honest, well-used condition. It is also still used for development work, being owned by Don Law Racing. In 2008, Don bought all of Unipart’s genuine, ex-Bloxham XJ220 parts stock and also holds the rights to manufacturer anything for the XJ220. As a result, Don Law Racing has become the leading independent specialist for the XJ220 as well as in Jaguar’s Group C racing cars and the XJR-15.

Climbing into an XJ220 takes a little practice to perfect; I heave myself on board with all the grace of falling over. However, once inside, the cockpit is surprisingly comfortable, albeit tight. I sit very low but ‘straight ahead’, the pedals and four-spoked Nardi wheel beautifully positioned ahead of me so there is none of the askew nonsense that plagues many Italian supercars. The view from the rear-view mirror – despite its size, it’s huge – seems to go on forever. The sports seats, wide dash top and gearbox tunnel are all covered in a high-quality grade of leather, but the rest of the dash could have come from Ford’s parts bin. The heater and auxiliary controls are from the cheaper grades of plastic known to man, while the dial pack couldn’t be more ordinary than if it wore beige slacks and was called Geoffrey. I do like the four dials set into the driver’s door, though, since they make the interior feel like a jet fighter’s cockpit.

As I turn the key (identical to that in an early Nineties Ford Escort) and press the huge red start button, the V6 explodes into life. Since the engine is literally right behind me, the cabin is filled with noise, which grows as I slot the stiff Ricardo five-speed box, modified to handle the V6’s 540bhp, into first and press the accelerator. In contrast to the F-TYPE’s V8 deep growl, the XJ220’s engine has a higher pitched mechanical wail (it would definitely hinder conversation if there were anyone brave enough to sit in the passenger seat alongside me), but the view out of the screen is fabulous. Wide, curved and with little of the car’s low nose visible, the screen gives a commanding view similar to that from the Group C sports cars.

With an open and empty country road ahead, I tentatively squeeze the throttle pedal. (I say tentatively because before I left Don’s workshop he told me the power on this car has been increased from 542bhp to 650bhp.) For a moment, nothing happens, then…

All hell breaks loose. The turbos catch up with my demand, sling-shotting me forward as if I’m a stowaway on the Saturn V moon rocket. The acceleration is so savage, I feel it punch me in the stomach and, just for a moment, I’m reduced to being a helpless passenger. When finally my consciousness catches up with me, I realise I’m fast approaching a corner. The AP Racing brakes – sharp yet progressive – slow this beast down enough to negotiate the corner without my becoming overly familiar with its surrounding dykes.

The rack-and-pinion steering is sharp, immediate and similar to a nimble go-kart, so the slightest twitch of the steering wheel results in movement. After safely exiting the corner, I change down. Now on the move, it is much easier to slot the manual ‘box into gear and navigate the lever around the gate. In third, I press the throttle… once again there’s a long pause before that massive rush of addictive acceleration arrives. To drive this car safely you need to plan ahead, to put your foot down before you want the power. It’s tricky, but very rewarding.

The suspension is race car firm: no body lean, and potholes are dealt with a thud. A fast series of left-right-left bends can be carved up with accuracy, the 220 remaining totally composed. But, never far from my mind, is the knowledge of the car’s vulnerability – and my own limits – that also comes from rear-wheel drive and no driver aids.

“If the XJ220 were a UFO, then the SVR would be an off-the-shelf jet fighter”

And that’s going forward. Reversing is an even scarier prospect. At 4,930mm long it might be 200mm shorter than the original concept, but it is still 455mm longer than the F-TYPE – which means that manoeuvering the XJ220 feels like trying to park a lorry, especially because the cockpit is so far forward and the majority of the car is behind me. With rear vision through the Perspex non-existent, and the wing mirrors next to useless, reversing the XJ220 takes faith. The XJ220 is a brilliant car that, despite its little faults and being 25 years old, a very fast one. Does the F-TYPE SVR keep up with it, in more ways than one?

Despite being a 575PS supercar, starting the SVR is less of an occasion than in the XJ220. Maybe it’s due to the car’s interior being largely identical to cheaper models, despite being better built with good-quality materials.

The F-TYPE is 140mm taller than the XJ220, yet there’s very little room and it manages to feel more claustrophobic. It doesn’t help that the interior is jet black and you need to be on close terms with your passenger. I suppose the better option would be to drive alone with no distractions.

The big 5.0-litre starts in an instant, the exhaust emitting a deep, dirty noise that has all the elegance of a barmaid’s cough. I pull the aircraft joystick inspired gear lever down to Drive (the SVR doesn’t have the option of a manual gearbox) and gently squeeze the throttle pedal. Acceleration is vicious and, unlike the XJ220’s turbocharged V6, the F-TYPE’s supercharged V8 responds instantly, its power delivered in one smooth linear arc. With 516lb ft of torque, that power never seems to end.

Without trying, I’ve quickly reached license-losing speeds and need to back off immediately. Yet the F-TYPE is less dramatic than the 220; there’s less theatre in how it accelerates and it does, in many ways, feel like a normal car, albeit a very fast one.

It’s not only the engine’s predictable power delivery that makes the difference – standard all-wheel-drive also plays its part. As a torque on-demand system, in normal conditions the AWD system sends 100 percent of the engine’s torque to the rear wheels. But, when intelligent driveline dynamics (IDD) determines that the rear wheels are approaching the limit of available grip, the electronically controlled centre coupling instantly transfers torque to the front axle. So whereas you need to tame the XJ220, I know that no matter how hard I accelerate, the F-TYPE’s clever IDD will do its upmost to keep me safe and pointing in the right direction. That’s not all. The SVR has a thicker anti-roll bar than the standard F-TYPE R and the rear knuckle is completely new. Now an intricate, weight-optimised aluminium die casting, the design of the part enables a 37 percent increase in camber stiffness and a 41 percent increase in toe stiffness, which all work to provide incredible grip. No matter how hard I push through a corner, there is not even a hint of oversteer and body roll is minimal.

Yet, despite the speed and the car’s GT3 image, the ride is actually very supple. The valves inside the continuously variable dampers have been revised and the control recalibrated. As a result, the SVR won’t crash and bang over imperfections in the road in the same way as the XJ220, or even the standard F-TYPE R.

The SVR feels less exciting to drive than the XJ220, though, it being shorter, taller and front-engined. Sure it’s fast, but to me a supercar needs more than just speed: it needs to be thrilling, too, like an automotive action film. And the XJ220, with its loud mechanical noise, low-slung racing-car-like driving position and incredible, if unpredictable, speed makes it one of the most thrilling cars I’ve ever driven.

Following the recently revealed 600PS XE Project 8, Jaguar’s membership of the 200mph club is further assured. Yet no matter how fast Jaguar’s become, none will ever be as exciting as its first member.

“A supercar needs more than just speed – it needs to be thrilling, too”

Thanks to: Don and Justin from Don Law Racing for allowing us to drive this incredible car (www.donlawracing.com/ 01782 413875)

BELOW RIGHT: Although the huge wing is required to keep the car stable at high speeds, the F-TYPE SVR’s shape lacks the purity of the XJ220’s.

ABOVE: Although well-built, the SVR’s interior looks and feels little different from that of an entry F-TYPE. ABOVE: The XJ220’s interior feels remarkably ordinary for a 200mph supercar although the dials inset into the door make it feel like a jet fighter.

XJ220’S REBOOT

The XJ220 wears alloys that were specially made for the car at the time; new tyres haven’t been available for over ten years. “Safety is an absolute paramount,” says Don Law. “It’s been a difficult situation and for many we’ve been using the last batch of tyres.”

Justin Law adds, “If the tyres were illegal, the car had to be parked.”

Until now. Bridgestone has designed a tyre for the car, developed at its Italian test track. As the original supplier, the Japanese tyre company didn’t just re-make the old version, it developed a brand new one, using modern technologies and the latest materials, while keeping the thread pattern’s look as close to the original as possible. The task was challenging because the molds had been scrapped, so all they had in the archives were old papers and drawings. In the end, Bridgestone made the XJ220’s extra wide tyres tougher by producing them on the same machinery used to produce tyres intended for motorsport, testing the prototypes on the very same car they used for the development work back in 1991: Don Law’s chassis 004.

The project reassembled the tyre’s original development team, including Andy Wallace, Alastair McQueen, John Nielsen and engineer Shinichi Watanabe, plus Bridgestone’s chief test driver, Andrea Dauri, and, as someone with considerable experience of the car, Justin Law himself participated in the project.

Says Justin, “It’s not just about knowing tyres. This is about knowing everything about the car and how it is supposed to handle. I’m one of the very few people that have been lucky enough to drive this car regularly during the last 23 years, and I’ve covered more than 100,000 miles.

“But don’t just take my word for it,” he continues, “with Bridgestone, we brought the engineers and test drivers from 25 years ago back together, so we were pretty much guaranteed to do the job right.”

INTERVIEW JIM RANDLE

SECRET AGENT The original XJ220 concept was the secret brainchild of Jaguar’s then chief engineer, Jim Randle. Twenty-five years after the road car went on sale, we talk to Randle about the original prototype and the problems he faced developing it for production. Words Richard Aucock.

JIM RANDLE We talk to the man behind the XJ220 – Jaguar’s former chief engineer, Jim Randle – about developing Jaguar’s first supercar.

Everybody was ignoring the Ferrari,” recounts Jim Randle, lynchpin of Jaguar engineering throughout the crucial, challenging days of the Eighties and father of the XJ220 supercar. “People were crowded around our stand, cheek by jowl. I then noticed that they put a girl on the stand – and as the day wore on, she was taking more and more of her clothes off. By the afternoon, a few heads did start to turn around…

“A time-lapse of her throughout the day would certainly have been interesting.”

Randle was speaking at Don Law Racing, the current custodian of everything Jaguar XJ220, as part of the car’s anniversary celebration held at the massive Silverstone Classic extravaganza in late July. Randle, designer Keith Helfet, and dozens of XJ220s were all guests of honour, 25 years after the production car came into being.

“It was CAD, you know: cardboard-assisted design”

It’s actually approaching 30 years since the project itself was born. I sit down with Jim in Don’s workshop to take us through the story. “It all started during the Christmas holidays in 1987. I always liked the D-type era of racing Jaguars, where they were not only raced on track, but driven to places like LeMans beforehand, too. It was a car that would happily turn from road car to race car. I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be nice if you could do the same thing again?’”

So, out came the cardboard. “It was CAD, you know: cardboard-assisted design. I’ve still got it.” Lots of the principals in this early model subsequently went into the V12 concept, he adds. It took him a week, after which he went into the styling studio with it, saying, “When you’ve got some time, put a skin on that… and I want it to be reminiscent of the XK 120.” (It was 40 years on from the launch of the 120.)

“They came up with two designs. One was this, the other was much more reminiscent of a Group C racer – a Porsche-type thing. I had to make a decision. They were both good cars, very well done… but I decided this one had more Jaguar in it. So, just after New Year’s Day, 1988, the project was underway.”

Famously, it was underway in secret. The evercharming Randle was a bit of a maverick at Jaguar, commissioning projects himself, and only presenting them to the board when they were finished. But, so perilous was Jaguar in the Eighties, privatised and working flat out to unshackle itself from the stupor of British Leyland, such projects could never continue in open view.

“I had no money to do this, and I could never have asked the board because they would never have given it to me. So I called for 12 volunteers – who weren’t going to get paid. Amazingly, I got 12. So we all started, divided the work up, and began meeting every Monday night in my office after work.

“Nobody was allowed to work in works’ time – if they got caught doing anything in works’ time, I’d probably have to sack them. They all knew that. Those were the rules. And they still stuck with it.” Each worked on his own area. Keith did the styling. “They made all their own decisions. If they had a problem, I’d help, but otherwise it was down to them. It was their bit.” And the only one who would chase them was another member of the group. “I didn’t have to say a bloody word.

“Twelve is a good number – Jesus Christ knew that. You can make a team out of 12 people. Make it any bigger than that and it starts to get troublesome – I worked this out myself mathematically. Just transferring information between people, even with the best management in the world, takes up so much time, you can’t handle it.”

But how do you develop a car with no money and no official sanctioning from the board with a tiny team of 12 people? You call in favours from your friends in the supply industry. “My job in all this, apart from tapping the design a bit here and there and suggesting changes, was to get the help of the suppliers. There were a number of them I’d worked with in the past who owed me something.

“So they came on board too, throwing in their labour, contributing to areas of the project at no cost. The only promise they got from me was that if it went into production I’d do my best to see that they got the work. That’s all – not even a promise to have the work, but that I’d try to see that they had it.”

And that’s how it went on. In ten months, it went from a quarter-scale cardboard model to the car that starred at the 1988 Birmingham Motor Show. Ten months – from nothing – to a showstopper. “A full working motor car,” adds Randle. “It can be done.”

Randle didn’t exactly have hundreds of people on hand to help, mind you. In the Eighties, one of Jaguar’s biggest engineering challenges was finding qualified people. Britain simply wasn’t producing enough good engineers. “You could generally find people, but you’d rarely find good enough people.” Randle found himself spending more and more time working with academic institutions to try to encourage young people to take up engineering, a path that would later see him head up Birmingham University’s automotive engineering department.

In the early Eighties, Mercedes-Benz’ engineering department was vast, with infinite resources and thousands of people working within it. Jaguar, says Randle, barely had 200. Under BL, it had been decimated, starved of investment, and the impact of this was clear.

Under chief executive Sir John Egan the turnaround began, something that was as reliant on winning the hearts and minds of the workforce as it was simply bolstering its ranks. Senior managers such as Randle were linchpins in this: they were respected, so could lead, and be followed.

The XJ220 project was the perfect example of this. “They worked every night, every weekend. Some of them even brought their wives along to make tea; keep them company. When it got really tight at the end, people were going in first thing, at 6am, then going to work at Jaguar, then going back to 220 to work until 10 or 11 at night. They were doing that night after night – and others were the same. “I went to see a hot sheet metal guy at 6am one morning. He was wearing the same clothes as the night before; it turned out he’d worked through the night, on his own, to finish this bloody job. I remember thinking, ‘This is incredible. If someone would do that… well, you’ve got him.’”

Remarkably, the secrecy continued throughout the project. “Sir John Egan didn’t see the car. The only people who saw it were the sales and marketing chap, Roger Putnam, and the manufacturing guy, Bob Dover – he would steal things for me from manufacturing, so he was okay.

It got to two weeks before the show, and John had still not seen it. So I brought him in. He saw it, then went away with Roger and Bob to a little room in the hot sheet metal department. We all sat around… ‘Is he going to say no?’

Of course, he didn’t – he was actually having a little trouble with the press at the time, so it was nice for him to show that we were doing something interesting.

“That’s how it happened: ten months, 12 guys, one XJ220.”

The next step was never planned. “It was always only intended to be a show car,” says Randle, “but such was the reaction that people were actually putting deposits down on it. By the end of the show, we had enough money for the programme. We knew we needed about £30 million to put it into production, and someone in sales and marketing suggested £40,000 would be a good deposit – by the end of the show, we had enough money pledged to do the whole programme without using any Jaguar cash.

“So from start to finish, it wasn’t actually going to cost Jaguar any money.” Alas, things are never quite so straightforward. “Sir John was soon raising the point that if it was done through Jaguar Engineering it would be a big distraction from the other programmes that were going on. In a sense, you couldn’t deny that. But you have to remember, if you have something like this going through, it pulls everything up with it. Everybody actually performs a lot better.” The board disagreed with Randle. The project was turned over to Tom Walkinshaw Racing – including all the deposit money.

“I think it was the wrong decision,” says Randle. “It was a bit sad, really. Keith was the only one who followed the project over.”

We all know what followed. Tom, explains Randle, decided to put the V6 in, to get it to market faster. Randle reiterates that you couldn’t deny the logic – and he says the team did make sure the press understood that it wasn’t going to be a 4WD V12 when it was launched. “It was absolutely clear at the time when we did the presentation. Sadly, lots of people afterwards said they weren’t aware.”

It ultimately ended up in the High Court. In Don Law’s workshop, Randle talks through the production car. It’s not quite as he would have done it, he reveals. The wheelbase is too short and the overhangs are too long, so it’s not quite in balance. He points to the shutline at the forward base of the door, “That’s just putting a very easy hinge line in, which I think is a spoiler: it doesn’t carry the lines of the car through. The show car opened as butterfly doors – I engineered that so the shutline mirrored the shape of the car.”

Randle is more pleased with how well integrated the car’s aerodynamics are. He didn’t want big wings and spoilers, but the car still had to generate downforce because of the extreme speeds it was capable of doing. A respectful relationship between design and engineering was behind the XJ220’s graceful lines, aided by advanced solutions such as the car’s flat bottom and the enormous dual Venturis beneath the rear of the car. Lots of time spent in MIRA’s wind tunnel was put to good use, Randle tells me, although he’s still not sure which department picked up the bill for it. Surprisingly, reveals Randle, the project did have a downside for the team.

“While it was a lifetime experience for all of them, in some ways, it was sad. They’d all done such a wonderful job and received full recognition for what they did, appearing in Car magazine and the like, but the guys back at Jaguar who weren’t involved didn’t like it – so in some ways, the 12 were ostracised. It was very, very sad, but that sort of thing does happen.”

To this day, Randle still sees the team today. “All they’ll want to talk about forever more is that experience,” he says. The thrilling experience of creating the XJ220 didn’t scar Randle, either. “I did it again, you know: the Lea Francis 30/230 – in 12months. Again, we went from nothing to presenting the car at the 1998 Motor Show. I still have that car.” Although he may not have an XJ220, he does still have the original cardboard model that he created over Christmas 1987, which in some ways is the most authentic and pure XJ220 of all.

Today, Don Law is helping the world’s XJ220s live on. Although they had never met before, there are the clear beginnings of a friendship between Jim and Don: both are enterprising, resourceful, polite and respectful. Walking around Don’s workshop, you sense Jim’s pleasure at the memories that are flooding back. “It’s funny, you know, all this happened 28 years ago, yet you suddenly remember things like it was yesterday.” Then, quietly, Jim and Don scurry away to a corner of the workshop, Don saying, “I’ve got something special to show you, Jim.” They return, beaming, saying nothing. It seems there may yet be a surprise in the remarkable story of the Jaguar XJ220 – and the man behind it, Jim Randle, couldn’t be more delighted.

LEFT: Prototype 005, seen here in August 1991, was sometimes used for customer demonstrations. ABOVE: the prototype’s exterior panels were hand-formed using this egg-crate buck. LEFT: The XJ220’s production line at the Bloxham facility. LEFT: Designer Keith Helfet (left) and Randle after the concept’s unveiling.

RIGHT: The XJ220 on Jaguar’s 1988 Show stand. LEFT: The XJ220 concept mid-way through construction RIGHT: the team behind the XJ220 conceot. Randle is to the far left. Jim Randle (left) and Tom Walkinshaw on Jaguar’s stand at the 1988 British Motor Show after the XJ220’s unveiling. The decision for TWR to produce the car was made at the show.