It was clear that the Lamborghini Countach which we knew and admired, was going to be the underdog. If the old champion was about to head for the high jump, as we believed it was, given that every respectable car commentator had been saying so in individual tests of the Maranello car, then we wanted the bold new pretender to have to prove its supremacy to us every step of the way.

As we weaved among the peak-hour traffic, there seemed to be quite a good chance that neither car would get a chance to show its real abilities. Yet we hoped for the best: the cars had come to us from Town and Country Car Rental, those bold people who can rent you anything from a Rolls to a Datsun Cherry and who have cut a swathe through the car hire business in the past few years. They’d squeezed our exercise into their busy schedule for the cars, so there wasn’t a lot of time to play with. Light snow was falling and though the weather forecaster on the radio spoke of dry periods in the west over the next couple of days, you could tell he didn’t really mean it. In America, he’d probably have taken the fifth amendment.

We were on the M4 by about 6pm (more than two hours after our planned departure time), resigned to the fact that any enjoyment of power and speed and agility was at least 100 miles away. Green in the Lambo was rediscovering that the car’s complete absence of rear three- quarter visibility made every lane-charge a gamble. And that his headlights were largely ornamental.

Leading in the 1984 Ferrari Testarossa, I was having trouble with a sticking throttle. I’d squeeze the power on to pass somebody (it’s all you have to do in these cars if you’re determined to stay under 100) and find that the horses were continuing to strain when I’d asked them to stop. I had to hook my foot behind the pedal to check the acceleration and so lessen the intermittent danger of ramming the occasional rep in an Austin Montego.

But things improved after we stopped at the first service area. Green discovered that some extra craning of the neck to see around the huge induction hump in the engine cover gave a modicum of rear visibility. I found that the weight of my foot on the clutch footrest had been jamming a rod which runs from a right- hand-drive Testarossa’s throttle pedal across to the car’s centre tunnel. As soon as I learned to rest my clutch foot with greater delicacy, the problem vanished. But I couldn’t help thinking that someone less fortunate might never reach my point of discovery, but would bury them-selves into the Armco instead.

Our plan was to peel off the M4 just above Cardiff, taking the fondly remembered A470 up through Brecon and Rhayader to its junction with the A44, which would carry us westward to Aberystwyth on the coast. Our art direction and photography types would already have established themselves in the Hotel Grand Belle Vue, on the seafront, having left much earlier in the day by Ford Granada. From there, the following morning, we would curl upwards for a time, then cruise back to the south-east, to the Severn Bridge and to Castle Combe racing circuit where we planned to show the cars some real speed and load.

It was the middle of the evening when we reached the better parts of the A470, beyond the well trafficked dual carriageways where policemen in BMWs were prowling. Despite the fact that we had stopped for an evening meal of molten-fat-with-sausages-and-beans, standard British motorway nourishment, we felt wide awake and very good about the fact that we had shaken off the soot of the city so thoroughly.

That was when we finally began to enjoy the cars – their effortless grip and pin-sharp steering, and the surprising traction of their huge rear tyres on roads kept damp in freezing conditions by the salt. Dominating everything was the towering 12-cylinder power of both cars, carried on a pair of the most blood curdling exhaust notes production cars ever had. At a twitch of the toe you could be carried toward at a far greater rate than your own body’s muscles could ever manage, even for a fraction of a second.

Gradually honing our somewhat rusty technique and getting used to such bulky and powerful cars again, we pressed along through the curves of the A44, getting faster all the time as we began to press the cars on turn-in. then boot them to the threshold of rear-end breakaway with the power. It all felt tremendously safe, comfortable even, because we travelled line astern and tacitly grasped each other’s muted excitement. The exhaust notes, rising further now, began to bounce back at us from the sides of frost-covered cuttings, to join the buzzes and whines and sizzles that are the dominating cockpit sounds of such cars.

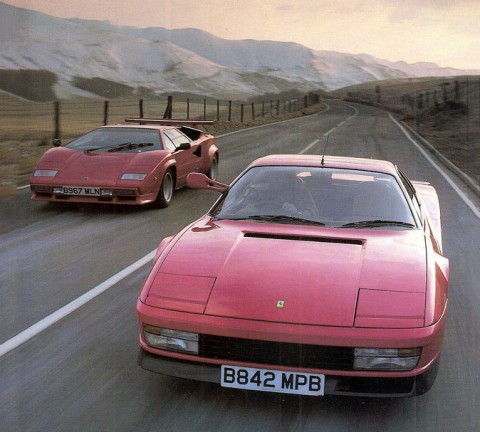

Ferrari’s sleek outline contrasts abruptly with bumps and bulges of the Lamborghini which features big rear wing for high speed stability. Testarossa has reasonable Cd of 0.36; tops 180mph. Lamborghini, far less efficient in the wind tunnel, needs 65bhp to go slightly slower.

By the time we reached the hotel, the cars had largely communicated their separate characters. Earlier, what we’d noticed were the similarities – the high levels of road rumble and the engine noises that dominated everything, the surprising wind noise, the enormous torque and flexibility of the engines and the eye-pulling power of both as they rumbled through towns that clearly hadn’t seen an example of either for many a moon. Tomorrow, we’d try to get to grips with the issues that were emerging.

What, for instance, was the source and extent of the Testarossa’s disconcerting tendency to tramline on longitudinal ridges, especially under braking? Did either car have a decent interior or was our initial disappointment with both justified? Did the Countach’s heavy controls constitute a big problem in long term or long distance use? Had the obvious effort Ferrari had put into simplifying their car’s controls damaged its character? Did the Lambo’s poor driving position interfere with one’s enjoyment of it? Did it really drink petrol to the extent it seemed to? And which of the pair was quickest In tough conditions like Castle Combe’s? We had two days to find out.

A warm reception awaited us in subzero Aberystwyth, both at the hotel and in the street. An enthusiastic group of local car appreciators had spotted our uncertain and rumbling progress through town. They gathered around as we pulled up at the hotel. Inside, our colleagues had prepared things well. As we went into the warm, we noted in passing that not every one of Aberystwyth’s car enthusiasts was male. Next morning there was confirmation. Written in a light and neat hand in the Ferrari’s salt-sprayed aides was: ‘Please marry me’.

The comparison between these cars is uncomplicated by the intrusion of other pretenders. The two Italians are unassailable. The Porsche 911 Turbo 930 and Aston Martin Vantage, which used to come close, are limited because their engines are in the wrong places. The same applies to hot Corvettes or super-heated German saloons or all manner of whizzbang one-offs. No other production cars have the blend of handling balance and roadholding, acceleration and top speed, style and eye appeal.

The Lamborghini is entirely the product of a few remarkable individuals. Designed in the first place by Marcello Gandini, it was painstakingly developed over years by the remarkable racing mechanic- turned-engineer. Bob Wallace, who gave up in frustration when he could not find tyres good enough for his cars. The Countach’s suspension was redesigned in the middle ’70s by Giampaolo Dallara for the Pirelli P7 which finally emerged (and which the car still wears). Those new low-profile boots were accompanied In the LP500S by a 5.0-litre two valves/cylinder version of the V12 (expanded from the original production car’s 4.0 litre) which had 390bhp under the lid.

Then, under threat from the Testarossa, Lamborghini’s new chief engineer, the brilliant Giulio Alfieri. redesigned the engine block for greater strength, replaced the sidedraught Webers with more efficient downdraughts, designed a four valves/cylinder head and procured for the car a hefty power boost.

As it stands in 1986, the Countach could quite well have been launched last week. It is still close to being the optimum supercar. The shape is as spectacular as ever (apart from that styling abuse, the rear wing) and apart from the fact that its cramped cockpit and poor rear vision is a little harder to tolerate this year than it was in 1974, the car’s layout is still close to the supercar ideal.

The car’s basic structure is a handmade multi-tube space frame of immense strength. It is clad in glassfibre inner panels and hand-finished alloy exterior sheets. Painting and rustproofing are all carried out strictly by hand, as are all of the major assembly operations. The four-cam, all-alloy V12 of 5.2-litre sits ahead of the rear wheels, driving forward to a gearbox mounted in the car’s massive centre just beneath the driver’s left elbow. Output from the gearbox is carried rearwards, by a shaft that goes back through the engine’s sump to the rear, limited-slip differential between the wheels.

Other specification details are as one might imagine they’d be if laid out today. The suspension is by double unequal length wishbones at both ends, which also have big diameter anti-roll bars. Each wheel has a massive power-assisted disc brake, steering is by manual rack and pinion (because power doesn’t have the feedback you need in stiff-suspension, quasi-competition cars) and each rear wheel also has twin spring/damper units to keep it under control.

The Countach’s striking specification is completed by its massive wheels and tyros. Unusually, it also has vastly different tracks front and rear. At the front (track 60.5in) the car has 225/S0VR1S tyres on eight-inch rims. At the rear the track is 63.2in and the car has remarkable 345/35VR15 P7s on 12in rims, through which to apply its power to the road.

The Ferrari Testarossa is a wholly smoother, more modern, more aerodynamic machine than the Lambo. It shows immediately in the drag factors: the Ferrari’s is reasonable at 0.36, the Lambo’s is an almost unmentionable 0.42 (without the wing, which must make it a lot worse, for all the stability it adds). What strikes you as soon as you see the Countach and Testarossa in company is the greater size of the Maranello car. It is nearly a foot longer at 177in, 2.0in longer in wheelbase at 100.4in, nearly 400lb heavier, more than 2.0in higher, similar in front track but nearly two inches wider in rear track. It is a big, big car. In overall length, the two-seater Italian is nearly three inches longer than a Ford Sierra…

The Testarossa’s basis, like the Lambo’s, is a tubular steel frame. Some inner panels are glassfibre but outer panels are mainly alloy, except for the most vulnerable pieces, for example, the doors, which are steel. The suspension is by coil springs, unequal length wishbones and anti-roll bars at both ends. The rear has twin suspension units for each wheel and the brakes are big, vented discs. Whereas Lamborghini doesn’t make encouraging noises about antilock brakes. Ferrari has already adopted the Teves system for its 412i, the front-engined two-door V12, and says it will be coming on the Testarossa, too. Steering is manual rack and pinion.

The Ferrari’s 4.9-litre engine is the superb flat-12, now with its four camshafts driving 48 valves instead of the 24 this car’s predecessor, the Boxer, had. The engine is mounted fairly high in the car because the gearbox and final drive are underneath. A clue to the fact that the power- plant’s centre of gravity is a little high comes from the fact that Ferrari chose to widen its car’s track to 3.5in more than the Boxer’s, which used the same power- unit and in early versions particularly, lacked rear roll stiffness.

On the performance front, you’d expect the Ferrari’s greater weight and size, plus its 390bhp, opposed to the Countach’s 455bhp. would make it the slower car. That is not the case. The practical conclusions are that the Lambo is miles faster to 60mph (5.0sec against 5.9sec) because its first gear will actually achieve 61mph true if you pull the 7400rpm red- line. But after that, the Ferrari’s better aerodynamics, and its more sensible second and third gear ratios redress nearly all of the balance. Both cars achieve 100mph in near enough to 12.9sec, a whisker short of the Ferrari’s third-gear maximum (of 103mph) but well short of the 119mph the Lambo will achieve in third. After that, the acceleration continues unabated with the greater power of the Lambo unable to offset its much poorer aerodynamics. Both cars are doing 120mph in 14.5sec, as near as you can measure it, and they run on to top speeds of just about 180mph.

Above 150mph, there’s no doubting that the Ferrari moves more easily. The Lamborghini, with wing, slows down noticeably. Besides, the Ferrari’s peak torque of 362lb ft is within an ace of the Lambo’s 370lb ft, and it is delivered lower down (4500rpm against 5200rpm). The Lamborghini without wing might be slightly the faster in still air, but owners seem to prefer the stability and the ‘Dan Dare factor* it adds to the car’s looks. Practically speaking, each of these cars is as fast as you could wish. Squeeze the accelerator at more than 3000rpm in either car and any gear and it will go like mad. Over 4000rpm, each car delivers a mighty shove to the small of your back and you will discover that at least five rates of rapid acceleration are available, depending upon whether you squeeze, push. prod, shove or mash the pedal towards its stop.

But, really, it is the cabin environment and the driving factors which define most clearly the distinction between these two cars. Oh yes, and the fuel consumption: the Ferrari gives 16mpg in places where you will get only 12mpg from the Lambo. We discovered, after complete familiarity had been established, that the two cars were like chalk and cheese, concrete and caviar, in the way they need to be driven.

The Testarossa is such a civilised car, it has a fairly soft ride which we felt was let down at times by extremes of surface roar and bump-thump from the Michelin TRX tyres. It is far firmer than a saloon car’s ride, of course, but no more so than, say, a Lotus Excel’s. There are times when, on undulations taken really quickly, you could hope for stiffer damping – and in corners you are surprisingly aware of the car’s body roll. But the pay-off is a level of comfort to your progress that won’t be found in other exotic cars.

The steering is firm by saloon standards, but needs no real muscle to manage. It is less direct than the Lambo’s but provides a decent turning circle, which, combined with the excellent visibility (about the best there is in a mid-engined car), gives the Testarossa a real town capability. The brakes are light to use, too, but over-servoed. You can’t just stab them as you might a set of stoppers intended for constant serious use.

The gearchange isn’t exactly fool-proof. No lever which must transmit nearly 400bhp can be that. But it moves fluently about its open gate with the characteristic ‘ker-snap’ of other machines which use the same system. The clutch matches the rest of the car’s efforts; it is light but a trifle woolly. But the Testarossa’s twin-plate clutch unit does have the virtue of being a full inch greater in diameter than the Boxer’s. That will please the many earlier flat-12 owners who had to replace standard clutches in 10.000 miles, or have had to suffer the heavy pedal and switch-like take-up of race specification units.

Inside, the Testarossa is a leather lover’s paradise. In the test car. the treatment was all tan with black dashboard (whose shiny top still reflected badly on the windscreen, just as the Lambo’s did) and it looked luxurious, even given that this is a 15,000mite car which had first been a demonstrator, then a hire car.

The leather bucket seats are comfortable and supportive of the body being conveyed at steady speeds, and their power adjustment combines well with the tilt-adjust (Fiat supplied) steering column, to give a wide variety of driving positions. The driver sits higher than is usual in cars like this (because the car itself is a couple of inches higher than the norm). The car suits people of far above average height and there is plenty of legroom too. Behind the seats there is a luggage shelf which can be used to accommodate £1000 worth of specially-tailored luggage. Another ‘Swiss millionaire’ touch is the huge vanity mirror that pops up like a jack-in-the-box whenever you open the copious glovebox. But the Fiat switches and controls are cheaper items than the buyer of a £63.000 car is going to like, and the truly awful instrument graphics – nasty italicised figures in yellow on dark green dial faces – wouldn’t do justice to a Toyota MR2. Same goes for the ‘parts bin’ digital clock and more dials, mounted in the ugly centre console.

Two things strike you about this interior: that one of Ferrari’s older, simpler interiors such as the Boxer or the 308 used to have would have been more in character; if a new. luxurious image was really needed, a wonderful opportunity has been missed. Try again Pininfarina.

The Lamborghini, once you’ve got over the look of it, is quite closely akin to a big kit car, to be brutally frank about it. Mind you. some people never get over the appearance. It is indisputably the more spectacular looking car of the two – we have the reactions of the crowds who surrounded it every time it stopped, to go by. Invariably there would be a clump of half a dozen people gathered around the Lambo, discussing its outlandish lines. The Ferrari, in this company, rated hardly a glance, however cruel that sounds.

Inside, the dominating thing about the Countach is a lack of headroom and visibility. If you’re more than about 5ft 10in, you have to slouch in the seat, bum forward, knees high, head retracted into the shoulders as far as is comfortable. The Countach’s steering wheel, smaller in diameter, is on a column that is adjustable for reach, not height. Most drivers find that they do best to extend the column so that the wheel is quite close, clearing the rising knees. Then the car can be driven with elbows tucked comfortably into the sides. It sounds awkward, and is for some, but both Green and I found it comfortable enough for 200 miles at a time (which is about when you’ll need to stop for fuel, anyway). Getting in and out isn’t as easy as it is in a wide entrance ’ordinary’ car like a Testarossa, but there is a certain appeal in developing a way with the Countach’s upward opening doors, and learning casually to insert one leg and your rump into the car before dropping into the seat and pulling your other leg in afterwards. The best thing is, as with so many aspects of this car, that it’s different.

The rest of the interior is, quite plainly, awful. If the Testarossa’s is bad. this is worse. Shiny black leather was the main trimming material of the test car and it just looked cheap, despite its undoubtedly hideous cost. If the Countach has aged at all, this is where it’s most apparent.

This, to be fair, is hardly the point of the Countach’s excellence. The point of the Countach – the thing which spells its superiority over the Testarossa in my book – is the way it goes when driven at top speed, maximum effort, full noise. At Castle Combe, we found the Lamborghini’s conclusive point of superiority.

Both cars did well. The 1984 Countach felt instantly at home, its heavy steering, gearchange and pedal efforts – and its compact driving position – suited the extreme loads of hard driving. But what told most was its superb capability over high speed bumps and its marvellous handling balance. It turned in best, it stayed flat under serious provocation, it braked without dive and it steered quickly and with precision. It behaved as many of the people who take pure track cars there would one day like their machinery to behave. I remember, in particular, its ability to control its body beautifully through a vicious dip at the end of the main straight, where the car (even as light sleet fell) was doing around 130mph. In the Testarossa it was safer to brake at that point, even though there was no impending corner to make it necessary. The Lamborghini’s better driver location (you sit in a tub. centre tunnel on one side and body sill on the other) made a difference.

Two remarkable cars, their design dates more than a decade apart, both have alloy panels fitted over tubular space-frame chassis. Countach is the shorter by more than a loot, lighter by 400lb but has massive 345/35 boots. Testarossa roar track is extremely wide.

All around was noise, of course. The gears under the driver’s elbow would scream in a way that would probably actually frighten the habitual driver of more staid machinery. But here it was: chassis and performance superiority from a car which, by now, should be outmoded. When the chips are down, the Lamborghini Countach is quicker, better handling, better braked, and nicer to drive.

After that, the Testarossa felt like a Ford Fiesta. Efforts required were light, it made less noise (but kept the pleasing ones prominent). It offered a nice, upright driving position and seemed almost airy in comparison with the Lamborghini. It rode better, too, but its steering didn’t have the bite, it understeered more (before threatening oversteer with roll at the limit). Its seals lacked the proper degree of lateral support for maximum effort corners, probably in the case of easy entry and exit, and its brakes felt a little spongy after very much work. Its areas of clear superiority were its gearchange, not nearly as heavy as the Larnbo’s and twice as slick, and its engine throttle response. That by a whisker.

It would be easy enough to write a conclusion about horses for courses. The Ferrari is easiest to use, and still has towering performance with an excellent chassis to accompany it. The Lamborghini is far more of a rowdy and uncomfortable brute, but people love its dramatic looks and it does offer a true taste of track ability.

But such a confrontation requires a decision, and it’s quite easy to make. The Ferrari is probably the best car of the two, but the Lamborghini is undoubtedly the greatest. Ferrari has shown how well it understands what Americans are inclined to call ‘the psychology of customer satisfaction’, and the Testarossa shows how little Lamborghini thinks it matters. That will be a point in the Ferrari’s favour.

But to us-to me, I suppose I mean-an exotic car is built for speed and handling and steering and going. Comfort and visibility are secondary. If you’re going to have a silly car, you may as well have the silliest of the lot, especially if it is the quickest and the best-looking, by a conclusive margin.

Ferrari Testarossa interior (lop left) is leather-clad in luxury though design detail misses the mark. But It’s roomy; driving position affords comfort and good visibility and seats have electric adjust. Flat-12 engine remains the finest in production. It’s even smoother with four valves/cylinder and no less flexible, though power output has risen to 390bhp. Instruments behind height-adjust column, are ugly.

Cramped Lamborghini cockpit (below right) is especially short on headroom. Seats don’t look comfortable but are quite supportive; steering column that adjusts for reach puts chunky wheel just where driver needs it for fastest driving. Gated gearchange is heavy but precise. Lambo’s V12 engine has even more punch than Ferrari flat-12 but is louder and less refined. Facia (left) is an unhappy mish-mash.