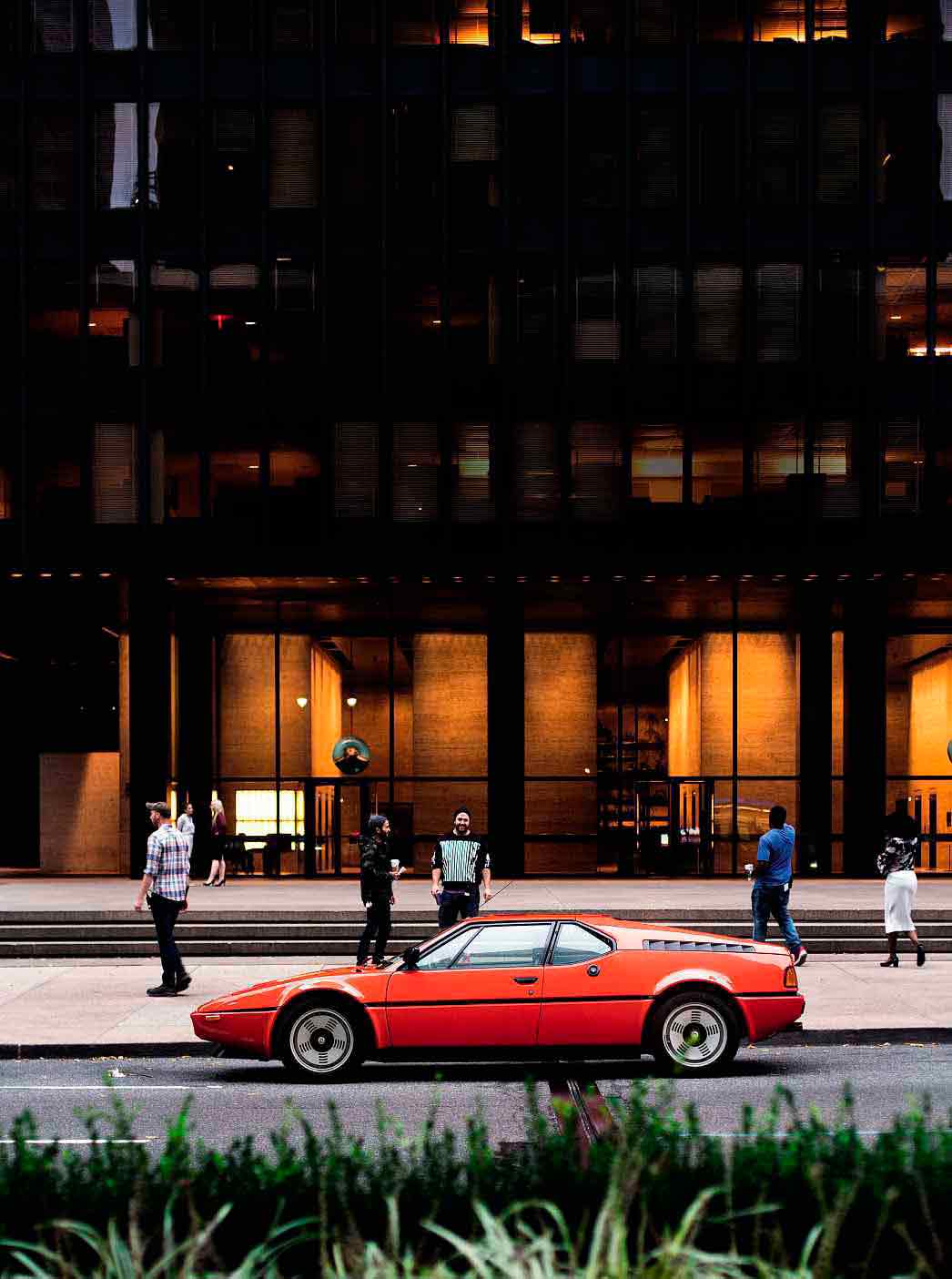

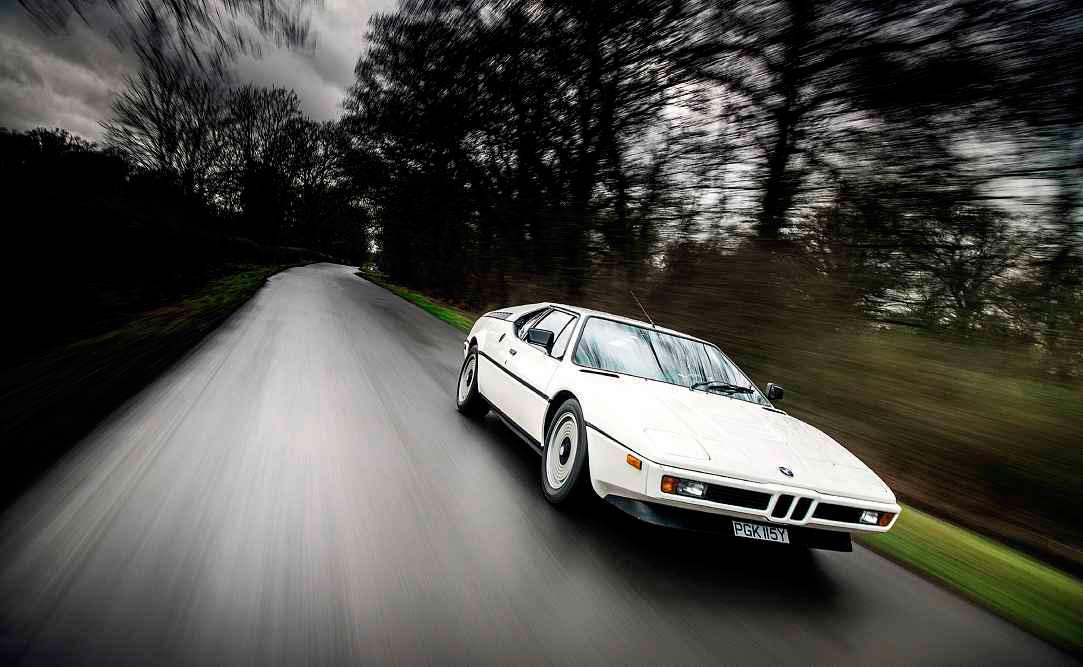

Night Rider. BMW’s M1 E26 was bred for the track yet turned out an unusually refined supercar. So let’s test it on the streets of Manhattan… Words Simon Aldridge. Photography Erik Fuller.

The darkest hour of the day is just before dawn. And at this ungodly hour, the neonlit quietude of Times Square is ruptured by the bark of a race-derived straight-six revving to the limiter and the explosions of unburnt fuel on the overrun, together announcing the arrival of the bright orange BMW M1 E26.

This is how Phillip Toledano enjoys his collection, in dawn raids on a deserted New York City. It’s six o’clock on a Sunday morning and we have some of the most famous streets in the world almost to ourselves. Born in London, Toledano is an artist and photographer who has called Manhattan home for over 25 years. When he started his car collection he favoured Italian beauties such as the Ferrari Dino 246 GT, Lancia Flaminia Sport Zagato and Iso Grifo. A chance encounter with an M1 E26 changed that.

‘I was at a dealer to drive a De Tomaso Mangusta, which is a stunning car to look at, but I was disappointed when I drove it. Then the dealer said “Why don’t you try the BMW M1 E26?” I had never thought about getting an M1 before that moment but, since I was there, I gave it a try… well, the first time I gave it some wellie it was like my balls were on fire! I haven’t looked back since.’

To translate for our international audience: Phil loved the M1, especially the howl and thrust of the race-bred straight-six as it neared the red line. He instantly became a convert to cars of its era and, in particular, competition cars for the road, such as the M, and other homologation specials. So, in addition to the BMW M1 E26, his garage now houses a Lancia Delta S4 Stradale, Lancia 037, Porsche 924 GTS Carrera Club Sport, and a Peugeot 205 T16.

‘These cars are just so special, and everything about them was there for a purpose – they were designed to win races, then turned into street cars, rather than the other way around.’

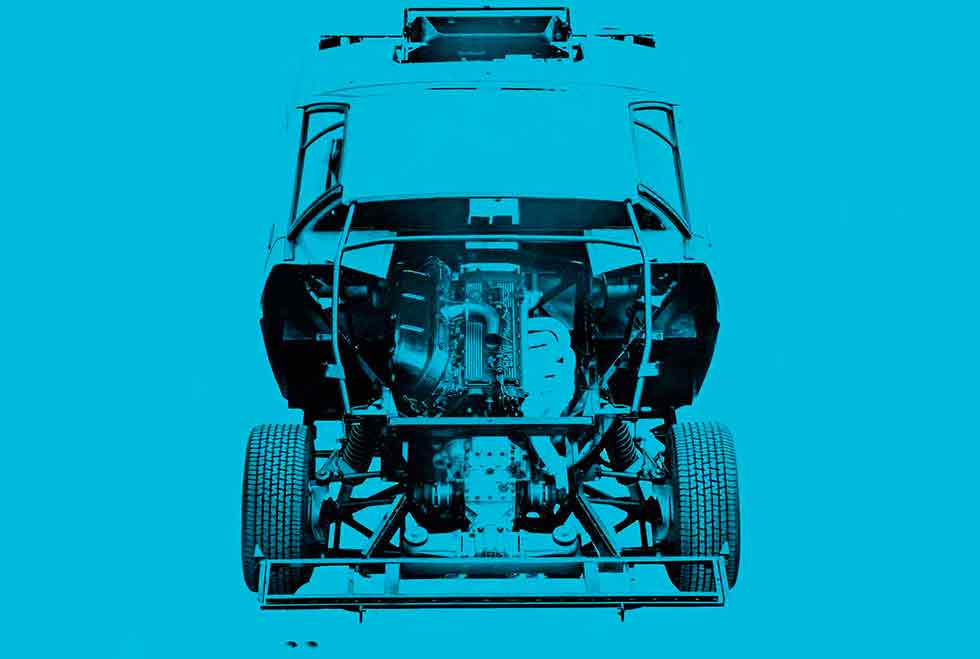

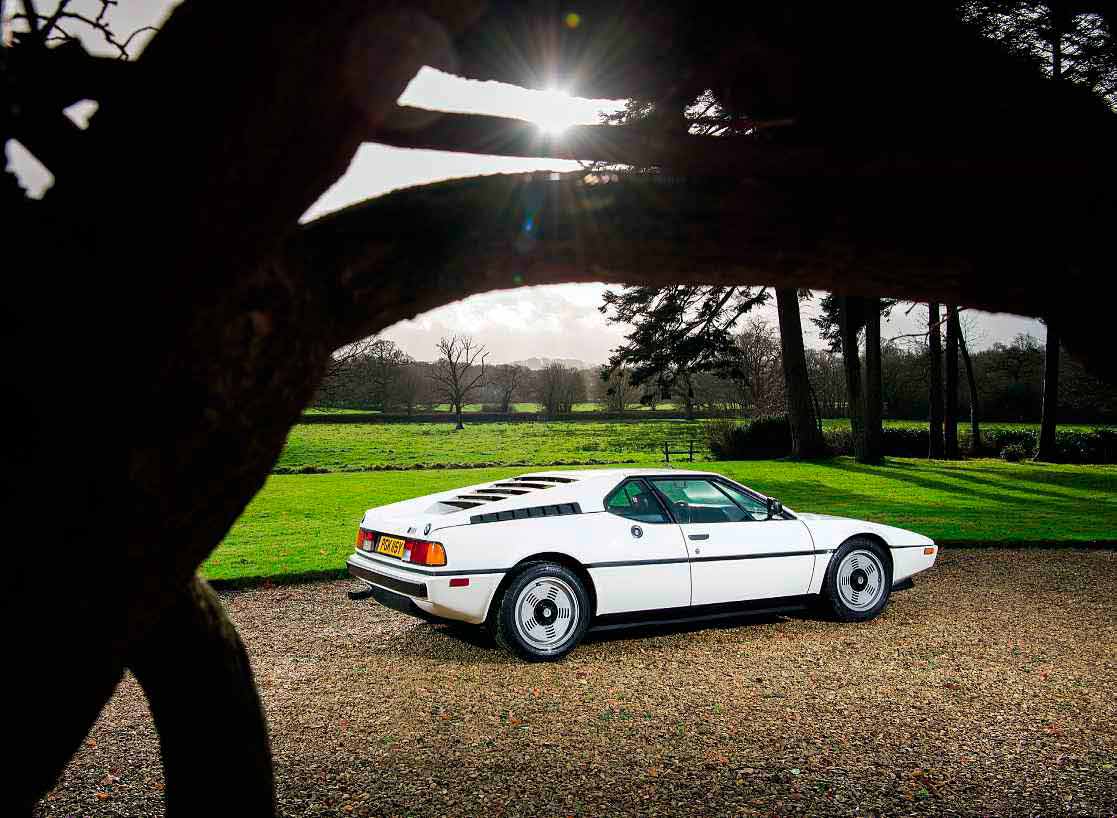

The M1 is a particularly well-resolved example of this. Look closely and those race-car details are evident everywhere, from the air intakes and airflow management of the bodywork, to the formula-car length of the rear suspension’s lower control arms, peeking out below the valance. Opening the engine cover reveals an engine set as low as possible in the chassis – thanks to dry-sump lubrication – yet there’s also a generous and practical carpeted cargo area. The Giugiaro silhouette is clean, sharp, elegant, and its glassfibre bodywork exhibits an unusually impressive level of fit and finish. So yes, it’s a race car, but one you really can use on the road.

In the modern context, the M1’s usability becomes even more striking. Watch it ride over the potholed avenues of Manhattan and the suspension actually looks supple. The ride height is reasonable and the tyres’ sidewalls – by today’s standards – are generous. And what streets these are. The lights of Times Square amplify the sensation of speed, while the walls of glass and polished stone reflect the M1’s orange wedge shape and its operatic voice to profound effect.

To say that the M1 is only about the engine would be inaccurate, but that straight-six is a masterpiece. Paul Rosche and his team had created a pure race engine – the M49/2 – for Group 5 and IMSA racing and fitted it to the 3.5 CSL race car, which Peter Gregg and Brian Redman drove to victory in the 1976 24 Hours of Daytona, BMW’s first major victory on American soil. When BMW decided to develop the M1 as a new purpose-built race car for Group 4 and 5 racing, it created a new version of that race engine designated M88/1, developed for the 400 cars required for homologation. Marque experts now think that only 399 street cars were actually built, plus a further 54 race cars. And you can read more about those.

Toledano’s car is one of the last built, a 1981 model that was BMW’s press car for a time, and it is in glorious original condition. As he pulls over by Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram building to let me take the wheel, Toledano is well aware that the charismatic engine has already made an impression on me. Access is straightforward and he sits quietly as I familiarize myself with the controls. The driving position is good – much better than the mid-engined Ferrari and Lamborghini road cars of the period – with pedals that are only slightly offset, and there is plenty of room for regular footwear. The gearbox, as befits a race car, has a dogleg first and then a straight H-pattern for the upper four gears. You are aware of long linkages at work to reach the ZF transaxle, but the movement is precise enough once you know the pattern and have learned the motion. Slick it is not, but it gives the impression of being bulletproof, a fact borne out by the race versions that, with turbocharging, produced more than 850bhp. The cabin is remarkably modern for a car that made its debut in 1978, with air-conditioning, electric windows and electric mirrors. It has a teutonic charm to it, with black hand-stitched leather covering the Bauhausian rectilinear forms. The seats have chequered fabric inserts that add to the grip of their bolstered sides, and the steering wheel is a unique three-spoker (although it was later used on the BMW M535i E28), with the BMW Motorsport insignia rather than the traditional blue-and-white BMW roundel.

The view out is unobstructed to the front and sides, with none of the bodywork visible. Towards the rear, however, it’s dominated by louvres and fins that shade the rear screen and channel air to the engine’s intakes around the side windows. It is a glorious riot of forms that remind you this was an Italo-German collaboration, designed by BMW together with Giugiaro and Lamborghini engineer Gian Paolo Dallara.

Toledano recommends that I pull away without too much tickling of the throttle, and as I make an experimental blip I understand why – the throttle has a sticky motion at the top, so tipping into it takes some commitment; it’s the result of a long and complicated linkage from pedal to six individual Kugelfischer throttle bodies. Combined with a light brake pedal, it makes heel-and-toe work a bit of a challenge if you are driving at anything less than ten-tenths commitment – no problem here in New York, of course.

I let out the smooth clutch with the engine at idle and pull away. Pressing the accelerator firmly to get past the initial stiction and shifting across the gate into second, the car feels ready for action, fluids warmed (thanks, Phil) and the engine eagerly waiting for the next burst of acceleration. That ‘begging for it’ attitude is one of my favourite aspects of race engines, and this one has it in spades. I shift quickly down into third and press the loud pedal deep into its travel again. The engine is screaming, egging me on to give it more all the time – Toledano is grinning in his seat and I am yelling that the engine sounds even more epic from my side. ‘Yes – the exhaust’s on the driver’s side!’ he grins.

‘ALL THE LIGHTS TURN GREEN AT ONCE, AND AWAY WE GO, UP THROUGH THE GEARS AGAIN’

The next few miles we spend snaking through slower traffic, accelerating into gaps and powering through the turns. The unassisted steering is not heavy and it’s very neutral in weighting, with little castor to make the self-centring stronger at speed. We turn along Park Avenue, cutting over Fifth to the Plaza hotel, where we park out front for a chat with some friendly NYC cops – they are big fans of the M1 E26 too. Later, sitting at the lights on Sixth Avenue feels like the start of a Grand Prix. All the lights turn green at once, and away we go, up through the gears again.

The West Side Highway is a chance to really open it up on some bends, as is the highway on the other side of the Holland tunnel, when we are en-route back to the anonymous garage building where Toledano houses his collection. Powering through some higher-speed turns, the chassis feels solid and planted, but at the same time light on its feet. It’s a neat trick that the best cars can pull off, and it makes the M1 seem years younger then it really is.

Contemporary road tests described the steering as one of the best features of the car, and I appreciate the transparency of its communication. At one point I enter a left-hander at speed, only to find that it tightens significantly towards the end, but the car instils confidence. Nothing happens when I back-off slightly on the throttle, the car remaining rock-steady, and the information flowing through the wheel (and seat of the pants) says that it has plenty of grip in reserve. It’s an impressive package, and one that you can imagine pushing hard over long days at the wheel.

Car and Driver tested a European-spec car in 1981 and published a result of 0.82g for its lateral cornering, which was pretty impressive for a car on 255-section tyres. Performance was on par with the leading supercars of the time but achieved through lighter weight rather than brute power – it’s hard to know which other car of 1978 could have kept up with a well-driven M1. The Lamborghini Countach and Ferrari 512 were significantly heavier, while the Ferrari 308 weighed around the same but had much less power. Only the Porsche 911 Turbo 930 came close, so it makes sense that on track the main rival to the M1 Procar was the Porsche 935.

The contrast between the M1 then and now is striking. It couldn’t be more relevant today, yet at the time it was overlooked. In period, for many journalists the M1 was a car that had already lost its raison d’être at launch, the silhouette formula for which it was developed having been cancelled during its long gestation. Furthermore it was emblematic of a failed partnership between BMW and Lamborghini, as it was caught up in (and delayed by) the Italian manufacturer’s bankruptcy. Many journalists who drove the M1 talked more about its usability and tractability than of its dynamic prowess. Here was a supercar that wasn’t as challenging as the Italians. How boring!

‘RACE-CAR DETAILS ARE EVIDENT EVERYWHERE – YET IT’S A RACE CAR YOU REALLY CAN USE ON THE ROAD’

We have enjoyed this M1 through the night into the day, and the sun is now rising. We let the car cool down and drink in its shape one more time, reflecting on the journey that the M1 has taken in the minds and hearts of enthusiasts. It is finally having its time in the limelight, having come of age. The M1 was a short-lived journey into supercars for the Bavarian marque but it marked a sea-change in how a supercar could be perceived, and how it could be used. Today, BMW builds the bang-up-to-date BMW i8 – a car that makes the current supercar crop look old-fashioned, even a generation behind. It’s something that, with hindsight, we can say the M1 did in 1978.

TECHNICAL DATA FILE SPECIFICATIONS 1981 BMW M1 E26

Engine 3453cc dry-sump straight-six, DOHC, 24-valve, Kugelfischer mechanical fuel injection with six individual throttle bodies

Power 277bhp @ 6500rpm / DIN

Torque 243lb ft @ 5000rpm / DIN

Transmission Five-speed manual ZF transaxle, limited-slip differential, rear-wheel drive

Steering Rack and pinion

Suspension Front and rear: MacPherson struts, coil springs, double unequal-length control arms, height-adjustable Bilstein dampers, anti-roll bar

Brakes ATE vented discs

Weight 1300kg

Top speed 161mph

0-60mph 5.4sec

{module BMW M1}

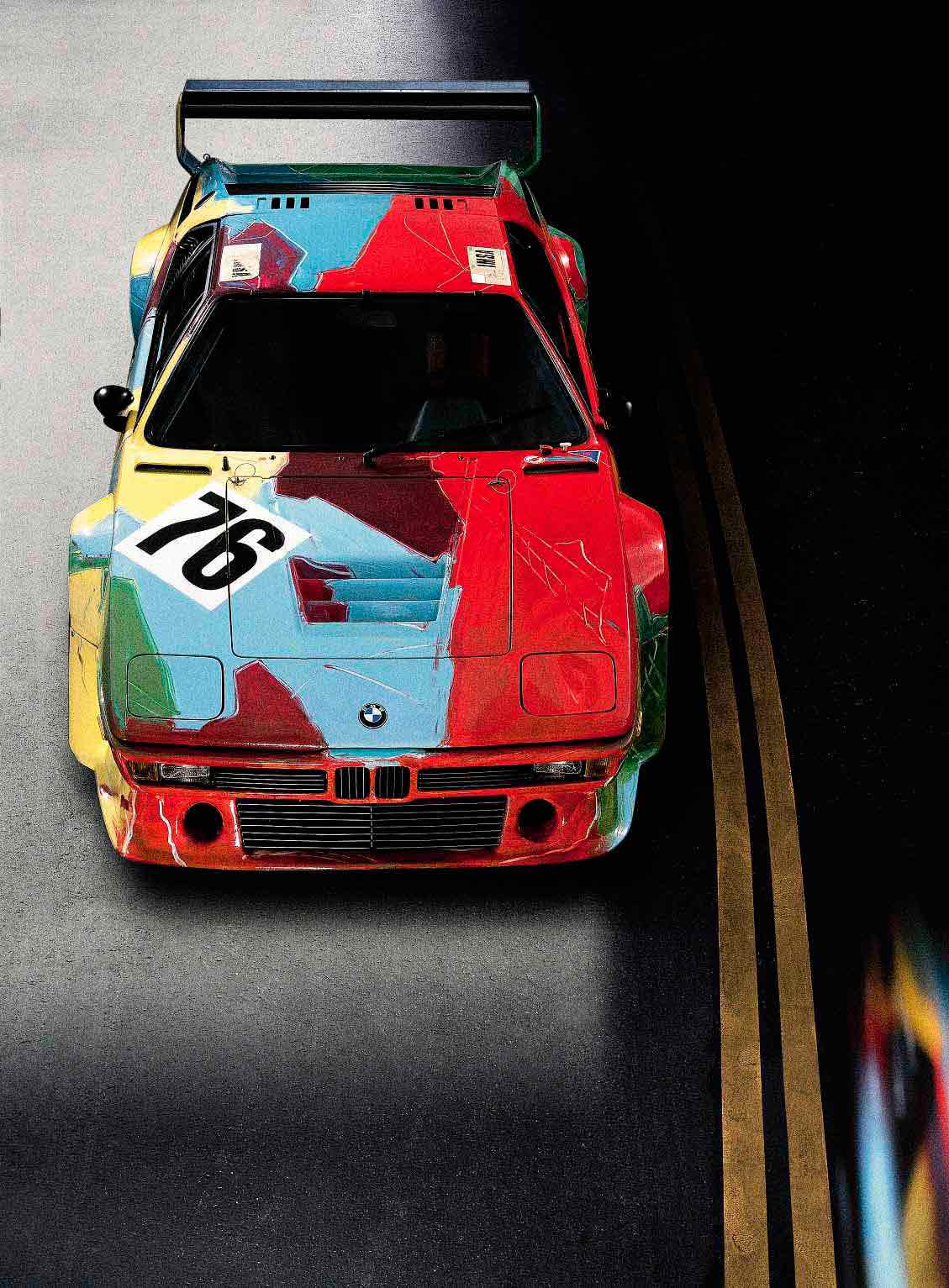

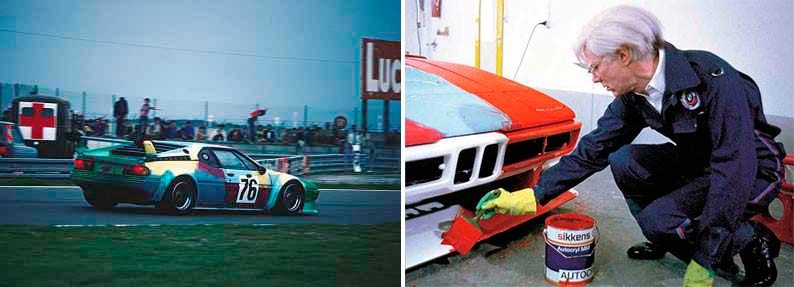

Andy Warhol Art Car

BMW M1 E26 Art Car famous for more than 15 minutes. Andy Warhol spent all of 24 minutes daubing paint on BMW’s Art Car no4 – long enough to render it immortal. Words Stephen Bayley.

Was there anyone who better sensed the pulse of the late 20th Century than Andy Warhol? ‘Iconic’ is an abused term, but Warhol understood that popular culture had acquired an almost religious resonance. He did not have an artist’s studio, he had The Factory with assembly lines… a place as significant to industrial New York as the Opera del Duomo was to Renaissance Florence.

Warhol proposed closing-down a department store so it could be preserved as a modern museum. He exploited celebrity, first of others, then his own. His career began as a commercial artist, drawing shoes. And then he became the most commercial of all artists. Making money, he once said, is the most beautiful thing of all. He wore a peroxide wig, aping his muse Marilyn. In a nightlife of flash photography, he was shot (with a gun) by a groupie-admirer.

And Warhol adored cars. In The Andy Warhol Museum retrospective in Pittsburgh, one of the earliest pictures was a drawing of his brother’s delivery truck. A nervous disposition and a regime of substance abuse were deterrents to a driving licence, but Warhol’s veneration of the automobile was sincere, even if it was often sardonic. With electric chairs, Hollywood, Elvis and supermarket packaging, they are recurrent in his iconography: his Silver Car Crash of 1964 recently sold for $106.5m.

A collaboration between austere Bavarian technocrats and the unchallenged leader of the downtown Manhattan art, drugs and LGBT scene may seem incongruous, but it became one of history’s happiest creative accidents, taking the collaborators places they might never before have imagined. BMW to the art-world vernissage, Warhol to Le Mans… at least in spirit. Alas, there is no record of what was going on, or coming down, in The Factory when Warhol took the call, but transvestites shooting up and nudes wandering in thigh boots were not at all, one imagines, like a BMW management board meeting.

Warhol’s 1979 M1 E26 was only the fourth of BMW’s Art Car programme, which began in 1975 with 3.0 CSLs painted by Alexander Calder, Frank Stella and Roy Lichtenstein. But not only was the car different, so was the artist’s engagement: Calder, Stella and Lichtentstein had painted 1:5 scale models with their designs and these were implemented by a Munich paintshop. It was remote. But Warhol was personal.

Largely ignoring the brief that the Art Car could be anything at all provided it did not interfere with racing performance, Warhol first proposed flowers and camo, then a scheme that was all brown… including the windows. BMW demurred.

So he decided to travel to Germany. None of the artists was paid for his work, but Warhol blagged the air tickets and installed himself and his entourage in the Vier Jahreszeiten Hotel, Munich’s swishest. And then he set to work. Of course, Warhol had said that in the future everyone would be famous for 15 minutes. In the event, it took him only 24 minutes to create the most famous BMW ever. There he is with his decorator’s paint and a three-inch brush, both heroic and absurd, intensely splashing away on a design of broad colour fields. If he was using sketches or a model, they are not obvious in the vintage video.

The intention, he intoned, was to suggest speed. But the beautiful paradox is this: in his gallery art, Warhol wanted to reduce everything to the shiny status of mass-production, uniform and characterless. But his BMW M1 E26 is an autograph work by his own hand. You can see and feel the expressive texture of the brushwork, just as you can in a Rembrandt. And, as if to emphasise the specialness of this project, Warhol signed his name in the wet paint of the rear bumper… using his finger.

The car finished sixth at Le Mans and during 24 hours some of the the paint separated from the body, as if in a metaphor. But who wrote the rule that art must be functional? In 1951, New York’s Museum of Modern Art had declared cars ‘rolling sculpture’. Warhol had created a racing picture. And BMW owns what is perhaps the most valuable car in the world.

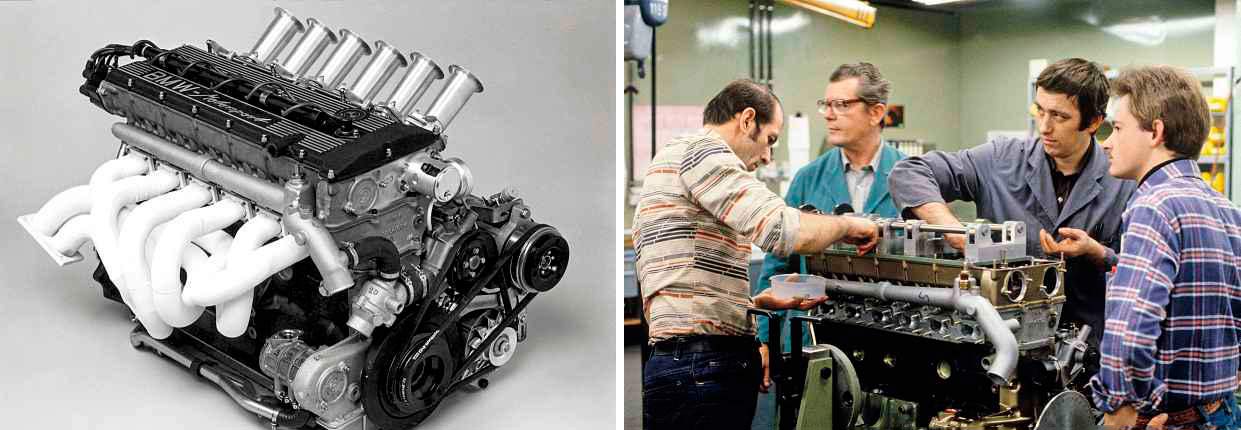

Legendary M88 Engine

BMW M88 engine the power and the glory. This straight-six’s origins date back to 1968, and it went on to power generations of super-saloons. But nowhere was its exotic nature better matched than in the BMW M1 E26. Words John Simister.

All these M numbers. A BMW M1 E26, obviously the beginning of the nomenclature. An M5, a rapid saloon in several generations. An M88, the two-digit numerals delineating not a car but an engine, the one found in the cars just mentioned. And M stands for Motorsport, BMW’s Motorsport Division within which much sorcery was concocted.

Paul Rosche was Motorsport’s man-who-mattered from the mid-1970s, which was when the idea for the M1 began to take shape. As well as the car itself, and the short-lived relationship with Lamborghini by which it would initially have been built had things gone to plan, there was an engine to create. It needed to be buildable at manageable cost and to be road-carreliable, especially as investment in a new motor could be recouped in cars beyond a low-volume, mid-engined supercar-cum-racecar. But it needed the power and glamour to match its high-profile first recipient.

Sticking with what it knew best, BMW Motorsport set about making the ultimate expression of the normally aspirated straight-six configuration that was at the core of the BMW brand. Rosche’s team already had plenty of form here, of course, most recently in the racing versions of the 3.0 CSL, whose engines were based on the 3.0-litre M30 unit that powered several BMW road cars of the time. The M30’s iron block, modified to include a bore enlargement from 89mm to 93.4mm, formed the basis of the new M88.

But the cylinder head – Motorsport’s first cleansheet design – was something altogether new: it was BMW’s first to have four valves per cylinder, and naturally there was a pair of overhead camshafts to actuate them. They did this via the popular arrangement of bucket tappets with shims between tappet and valve stem, the thickness of the shim determining the valve clearance. More unusually, the camshafts were housed in their own separate ‘layer’ above the main cylinder head casting, sandwiched by the head below and the ribbed cam cover, with its ‘M Power’ logo, on top. Drive to the camshafts was via a duplex chain.

Apart from the cam cover, the M88’s other distinctive visual feature was the six separate throttles, one for each cylinder, housed within the six short intake pipes that emerged directly from the airbox. That’s a very racy induction system but it’s one that carried over into the M88’s various roadgoing applications, too. Fuel injection was by a Kugelfischer mechanical system, complete with a six-cylinder pump much like that of an old-school diesel engine.

A stroke of 84mm gave a 3453cc capacity, with a peak power of 277bhp at 6500rpm as fitted to roadgoing M1s. The Procar racing versions gave much more: 470bhp at a remarkable 9000rpm – remarkable because a straight-six’s long crankshaft is subject to torsional vibrations that, while they largely cancel each other out internally so the output at the flywheel is famously smooth, nevertheless generate a lot of internal stresses. BMW Motorsport learned how to work around the problem in those 3.0 CSL E9 racing engines, and the M1 Procar units are among the highest-revving big-capacity straight-sixes ever.

As well as the Procar series, the M1 found itself entered in regular mixed-make motor sport. This ultimately led to the development of a Group 5 version with twin turbochargers and 950bhp from an engine designated M88/2, demonstrating the strength of what was still a production-based cylinder block. BMW Motorsport later made that point even more forcibly in Formula 1’s first turbocharged era, using four-cylinder M10 blocks – the M30 was in effect one-and- a-half M10s in its original guise – for racing engines able to produce four-figure power outputs.

After the M1 production programme ended, BMW Motorsport experimented with fitting an M88 into a suitable regular BMW road car. The most sporting prospect was the 6-series coupé that had replaced the old 3.0 CSi and CSL E9, and in 1983 the M635 CSi E24 duly appeared. A few changes were made to the M88 motor along the way, the resulting M88/3 featuring a single-row timing chain and the replacement of the complex, potentially finicky and by-then-outdated Kugelfischer injection with an electronic Bosch Motronic unit. This used an airflow meter at the entrance to the nowslimmer airbox that now covered those six intake trumpets, still with their individual throttle bodies.

In this form the engine actually produced slightly more power: 286bhp, still at 6500rpm. With this came a small boost in peak torque to 251lb ft at 4500rpm, this peak usefully occurring 500rpm lower down the rev range than it did for the M1’s 243lb ft. Now that more people were having a chance to try it, the M88 engine gained ever-more praise from those who experienced its broad band of smooth but crisp-edged energy, its howl as the revs rose and the pace fortified. Truly, it was a fabulous thing.

In 1985 the M88 was further democratised by being installed in the first M5. This ultimate and wonderfully understated version of the E28 5-series, a range launched in 1982 yet remarkably similar in appearance to the one it replaced, was extremely entertaining; few people even knew what it was. The next 5-series down in the range hierarchy, the 535i that used the same 3.5-litre block but the regular single-cam head, could be had as a body-kitted M535i version that looked much racier than the M5. Looks deceived.

When the E28’s time was up in 1988, it was replaced by the handsome E34 (designed under the eye of Ercole Spada, once of Zagato, by then a consultant at the IDEA Institute just outside Turin). Naturally an M5 version soon arrived, understated again, its engine redesignated S38 in line with a new BMW numbering system. A 2mm increase in stroke raised capacity to 3535cc, and power rose to 315bhp at a heady 6900rpm despite the presence of a catalytic converter.

How could this be? Did it mean that, despite the irksome emissions rules being imposed by authorities, engines could still be vibrant givers of petrolhead pleasure? Such were the concerns of enthusiasts in the late 1980s, and the M5 – arguably the finest sporting saloon of its time, and greatly enjoyed by this writer – proved that the cake could be both eaten and yet still possessed, as many other high-performance engines have since confirmed.

The S38 incarnation of the M5 motor, though, was probably the first to do a convincing job in that regard. It did it with a combination of higher-lift camshafts, freer-flowing ports and manifolds, replacement of the flap-type airflow meter with a less restrictive hot-wire type, and a new variable-length intake system within an enlarged airbox, still feeding six separate throttles. The timing chain regained its duplex construction, too, given the greater revvability and the higher loads generated by the increased valve lift.

In 1992, another 4mm of stroke increased capacity to 3795cc and the valves and throttle bodies were enlarged to suit. A more sophsticated management system controlled distributorless ignition with a separate coil for each sparkplug, and outputs rose to 340bhp (still at 6900rpm) and 295lb ft at 4750rpm. To emphasise that this was still very a much a Motorsport engine, its bigger-bore exhaust manifold was made from Inconel, a very hard and heat-stable alloy still used today for the exhaust manifolds of Formula 1 cars.

And thus the S38, or M88/5 as it would no doubt have been called had the naming system not changed, continued until 1996. Subsequent M5 generations were powered by a V8, a V10, and V8 turbos.

The demise of the M88 and its S38 evolution marked not only the end of BMW Motorsport’s best-known and most revered engine, but also the end of the road for a rather historic engine block. That M30, introduced way back in 1968 for the 2500 and 2800 saloons, was BMW’s first post-war straight-six. On that fact, and the reputation that arose from it, are a fair chunk of BMW’s modern brand values made.

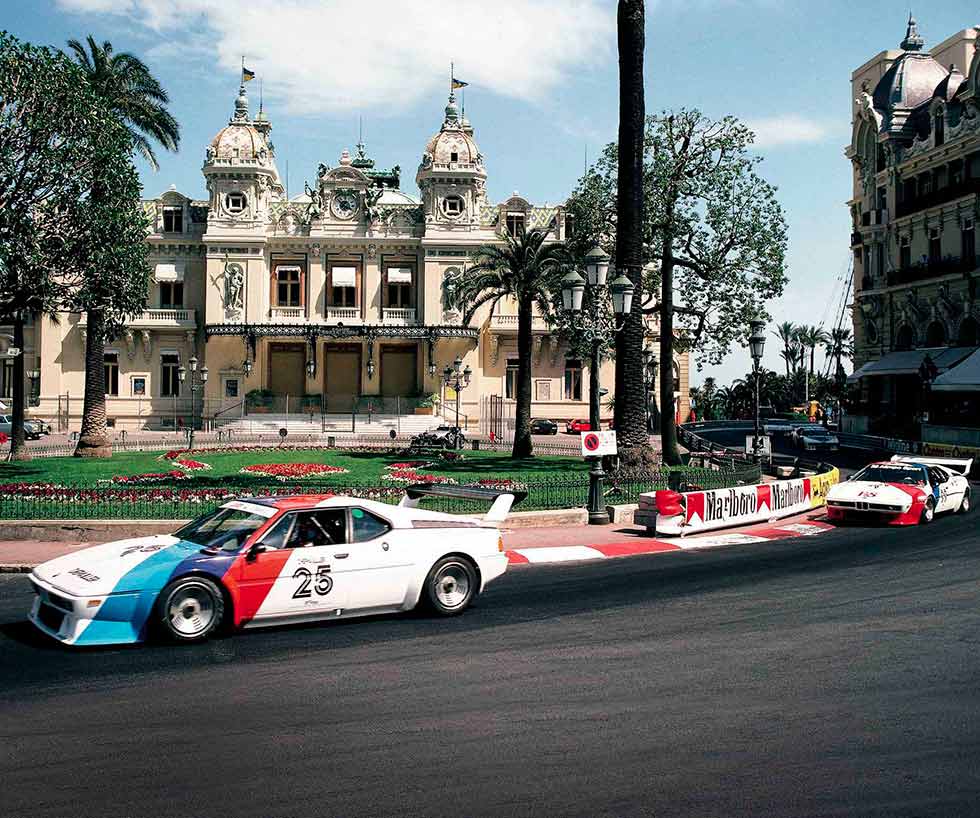

Procar Racing Series

BMW M1 E26 Procar Second Prize. Denied the chance to compete in Group 5, the BMW M1 became the hero in its very own Grand Prix support series. Words Richard Heseltine.

You had to feel for Jochen Neerpasch. Scroll back to the late 1970s and the general manager of BMW Motorsport GmbH had worked tirelessly to see his vision of a racing car enter production. Nevertheless, the squeeze was being put on the former works Porsche driver to get results trackside. This swiftly became a chokehold. The ’1978 season had been and gone but it appeared as though the M1 would be out the following year. Then the FIA changed the rules for the Group 4 category of the World Championship for Makes.

The plan had been to build 400 road cars, to appease homologation requirements. With the hurdle vaulted, BMW could then compete in the Group 4 class but, more importantly, field a small number of evolutionary Group 5 cars that would run at the sharp end. The FIA then insisted that BMW not only build 400 cars, but also sell them in the requisite time. No chance.

So Neerpasch’s scheme was in ruins. Fortunately, he was able to save some face on conjuring the ultimate one-make race series. Procar would be the support act to eight rounds of the Formula 1 World Championship, with the top five qualifying GP drivers – or those whose contracts would allow them to compete in other manufacturers’ cars (so no Ferrari or Renault players) – driving M1s. They would do so against an army of European Touring Car Championship stars, sports car aces and assorted privateers.

The be-spoilered, 450bhp Procar M1s were constructed by BS Fabrications, Ron Dennis’s Project Four concern and Osella. The series was a smash in every sense, the public clamouring to enjoy the very close – sometimes too close – racing, with Elio de Angelis winning the inaugural race at Zolder in May ’1979. Nelson Piquet, Hans Stuck and Jacques Laffite also claimed silverware that year, but three-time victor Niki Lauda bagged the title.

Into 1980, the series changed tack with nine rounds, not all held on Grand Prix weekends. Piquet, in only his second full year of Formula 1, secured three consecutive wins and the drivers’ crown. He has since claimed that he took winning the championship more seriously than his rivals. He wanted to showcase his talent against the stars of the day while topping up his wages with prize money. It is fair to say that some veteran drivers treated Procar as an excuse to get physical with friend and foe alike, away from the serious business of winning a Grand Prix.

Sadly, there would be no Procar in 1981. Principal sponsor Goodyear pulled out and the turf war between F1 bodies FISA and FOCA spilled over into a pitched battle. A one-make series was just a distraction. Instead, BMW regrouped and focused on its Grand Prix engine programme. The M1 represented an expensive flirtation with hubris and there were casualties, Neerpasch among them. Nevertheless, he would go on to find great success with Mercedes-Benz – boosting the career of Michael Schumacher among others, thanks to its Group C Junior Team programme.

Owned For 30 Years

Owning a BMW M1 E26 MY 30-year love affair. This serial BMW aficionado bought his M1 in 1987, so he’s qualified to offer some advice. Just don’t expect him to part with it… Words James Elliott. Photography Paul Harmer.

‘Never under any circumstances try to jumpstart a BMW M1 E26,’ says Eric Verdon-Roe. He has good reason… plus an angry-looking warning label beside the battery. Why so? ‘It generally starts first time, however long the lay-up, but there was one occasion when it simply wouldn’t go. We traced it to a blown “black box” and I was horrified to find out that the cost of a new one was £1400 plus VAT. Three years later the problem occurred again. This time I had to contact BMW Germany to source a replacement at no less cost.

I then found out through a casual conversation that this particular unit is fried if you jump-start the car, so we twice turned a simple lack of juice into a cripplingly expensive immobilisation. Never again.’ But this is what you learn when you have lived with a car for 30 years. The boss of motoring book company Evro (www.evropublishing.com) and former MD of a publishing house is uniquely placed to give the longterm ownership view of a car that may be robust by supercar standards, but is still fragile in comparison with the mainstream – especially in middle-age.

Not that it looks it: to Verdon-Roe it is as desirable as it ever was: ‘Every petrolhead will remember “that picture”, the one from your youth. It was 1972 when I took my car to be serviced at a BMW specialist and on the wall I saw the first picture of the BMW E25 Turbo, a gullwinged, mid-engined supercar. I thought it was fantastic and just imagine: a car that looked as good as an Italian one but that would actually work!

‘The idea of owning such a car bubbled away for many years and my love of BMWs in the ’70s and ’80s resulted in me owning a BMW 2002 Targa and a BMW 2002 Turbo before a series of Porsche 911s took over.’ When the ItalDesign-penned BMW M1 (E26) came out in 1979, the heritage was obvious and, while not so wild as the Paul Bracq-designed E25, it stayed true to the concept of an Italian-style car (though Bracq was a Frenchman) with solid German engineering. It’s not just about the looks, though.

‘The six-cylinder 3.5-litre M series engine was shared with the original E28 M5, with the addition of drysump lubrication to reduce the centre of gravity. It kicked out 277bhp, which is now what a warm hatchback can achieve, but back then it could keep up with all but the most powerful Porsche. The unique, for BMW, mid-engine layout would have allowed you to watch in the mirror as a contemporary 911 disappeared backwards into a hedge.

‘I loved it and the passion only increased with the BMW Procar Championship that raced before Grands Prix in 1979 and 1980. Seeing Grand Prix drivers treating them like slot cars around circuits like Monaco was as exciting to the spectator as it must have been terrifying for the entrant.’

In the end it was just a matter of finding the right car from fewer than 400 built by Baur, its success tempered by production being delayed by four years thanks to the inevitable bankruptcy of Lamborghini, which had been contracted to construct it.

Eric started scouring the market in 1988, and heard from a friend who was travelling in the USA and had stumbled upon an ‘absolutely as-new’ 12,000km M1 being brokered out of an Oklahoma Nissan showroom by one Rocky Santiago. The price was $95,000, which translated to about £48,000.

It didn’t take long before Eric learned some harsh financial realities: ‘The price had become £86,000 by the time transport and taxes had been paid. This included work by L&C, who were the acknowledged M1 specialists. We had to remove the USA-fit catalytic converter and found that the engine needed rebuilding as it had been run on the wrong oil and fuel, causing glazing to the cylinder bores. A Mobil consultant sent by BMW UK suggested that a 20/50 oil should be used and that the engine should be run-in by being driven hard over a long distance. Which I was happy to do.

And while the engine was out we replaced the clutch, which can be done only by dropping the engine.’ So, not the bargain it had first looked, yet still worth it for such a low-mileage example with a nearuntouched interior. Not that the interior is all that special, although, ironically, the fresh air vents in the doors (sourced from the Fiat 124 Coupé and once standard UK scrapyard fodder) are now super-rare.

It isn’t roomy either, and 6ft 3in Verdon-Roe admits he can’t really fold himself into the classic Italianate long-arms, short-legs driving position. Restricted headroom forces him to drive with his head tilted and pressed against the roof, while the abysmal rear visibility ‘often requires a special angled approach at left turns to enable any view of oncoming traffic’.

Before it starts to sound too much like a dismally unhappy marriage, there are plenty of reasons why Verdon-Roe has stuck with the M1 for 30 years. ‘It has always been a joy to drive and feels like a much more modern car even today,’ he says. ‘The steering is particularly sharp, allowing you to place the car precisely, and the relatively soft suspension is wonderful on Britain’s B-roads. In these conditions it is bettered only by a Honda NSX.

‘I have owned a lot of cars over the years and I have been tempted to sell most of them at one time or another, but it has never entered my head to sell the M1. It’s a keepr. And I know my son is keen to keep it in the family when I pop my clogs – or earlier, if old age means I can’t get into it any more.’

How M1 Inspired i8

BMW M1 E26 concepts back to the future. BMW doesn’t officially say so, but there’s a discernible link between M1 and today’s i8. Words Mark Dixon.

Look at the picture above. It’s of a concept car, the M1 Hommage, and it dates from 2008. Now compare it with the i8 Concept, top right of the facing page, unveiled just three years later. It’s very different, but there are similarities, yes? Same wedge profile, same squashed BMW kidney grilles, same horizontal strip containing front lights – all of which were present in the 1978 original M1. Which itself was derived from the Paul Bracq-designed 1972 Turbo concept E25.

BMW likes its concept cars. Sometimes they’re remarkably close to a forthcoming production model – like the i8 Concept – and sometimes they’re completely off-the-wall. The fun lies in trying to predict which category the latest flight-of-fancy falls into. For example, in 2008 BMW also revealed the Gina roadster concept by head-of-design Chris Bangle.

Its carbonfibre rod-framed body was covered in Spandex; the idea being that it had almost no visible seams, so, if you opened a door, the fabric simply wrinkled back where it covered the door hinge. We’re still waiting for that idea to storm the mainstream.

The following year, BMW unveiled its 2009 Vision EfficientDynamics concept (yes, with irritating lack of a space between two words) and it seemed equally fantastic. It didn’t just look impossibly futuristic – an overhead view is shown, right – but it also had a powertrain that coupled a three-cylinder, 1.5-litre petrol engine with electric motors to promise staggering performance with then-unimaginable fuel economy. Yet within two years the VED concept had evolved into the i8 Concept, which doesn’t look very different from the production i8 that’s been on the market since 2014. The Gina concept? A little bit barking. But the VED… not so mad after all.

Remarkably, the VED appeared just a year after the M1 Hommage, which was a clear, well, homage to the original M1. The infamous Bangle ‘flame surfacing’ design language is detectable, but there are also more M1 cues than you can shake a laser-pointer at. The M1 Hommage even has twin BMW roundels at the rear, one above each tail-light, just like an M1.

At the time, BMW claimed the M1 Hommage was simply a celebration of the original M1. No-one really believed the company, however, and it was clear that BMW was casting around for a new halo model. While the eventual i8 took the marque’s design in a whole new direction, it does feature scissor-style lift-up doors that are not too far removed in terms of visual drama from the 1972 Turbo concept’s gullwing equivalents. Paul Bracq must be feeling vindicated.

‘THE BMW M1 HOMMAGE AND THE BMW I8 CONCEPT ARE VERY DIFFERENT, YET THERE ARE SIMILARITIES’