On track in Ferrari’s glorious 917 challenger. Ferrari 512M track test Group 5 great driven at Paul Ricard. Flat-out in Ferrari’s legendary 512. Maranello strikes back. Beautiful and charismatic, Ferrari’s 512 offered only glimpses of its potential against Porsche’s mighty 917. Marc Sonnery gets behind the wheel to tell its story. Photography James Mann/LAT.

The changing world of sports-car racing at the end of the 1960s proved challenging for Ferrari, especially after the Porsche 917 stunned the automotive world at the 1969 Geneva Salon. Following the introduction of new 3-litre regulations, the German company’s exploitation of a loophole allowing 5-litre engines if 2 5 identical cars were built was a step that few had foreseen, but it was a path that Ferrari was forced to follow It instantly rendered obsolete Maranello’s gorgeous new 312P, and the 512 S was born only months later.

The context was somewhat fraught because the new car had to be developed alongside Formula One, Formula Two and Can-Am programmes. It was a period during which the company’s resources were truly strained.

“The project just preceded the arrival of Fiat’s money in 1969,” explains Mauro Forghieri, the former head of the racing team. “It was a new model in respect of the rules it had to follow, plus the bulkier engine and transmission [compared to the 312P], but because it had to be built in numbers, costs were important. We used existing models and modified them. Due to the delayed decision [to go ahead] and also to other tasks, the project lasted only two months, but our strength was that we were a united team.

I was just the head for all the technical ideas.

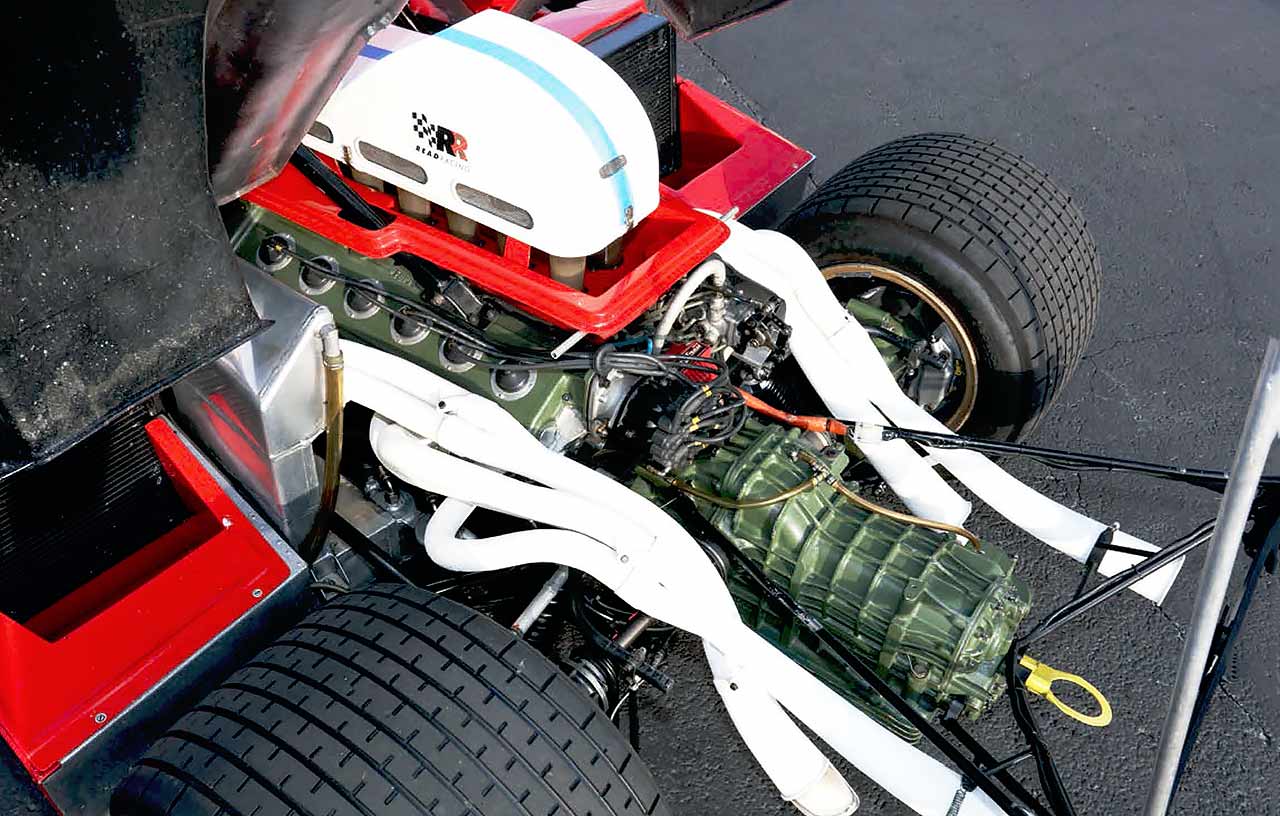

Based on recent creations such as the Can-Am 612, the 512S used a semi-monocoque tubular chassis with double wishbones and coilovers at each corner, while the 4993cc, quad-cam, 48-valve V12 gave 550bhp at 8500rpm. There would be Berlinetta and Spider variants, and some of the body sections were in polycarbonate, which was such a new technique in Italy that Ferrari had to subcontract the work to shipyards and even to manufacturers of fairground rides.

The 512S was introduced to the press in December 1969 at the Gatto Verde restaurant in the hills above Maranello, Alter precious little testing, it was cleared to race by motorsport’s governing body, the CSI, just days before the Daytona 24 Hours. While the 512s were obviously quick – Mario Andretti took pole position – they were still raw. Four of the five examples that were entered failed to finish; Andretti’s car, which the American ace was sharing with Jacky Ickx and Arturo Merzario, limped home third, 48 laps behind the winning 917. Porsche’s six-month headstart was already all too obvious;

The Sebring 12 Hours brought what would turn out to be false hope. Andretti grabbed a last- gasp victory, having been reassigned to the Nino Vaccarella/Ignazio Giunti car after his own failed. He hunted down the Porsche 908 of Peter Revson and “that actor guy” Steve McQueen, spurred on by the hype surrounding the latter. It would be the 512’s only Championship win.

Many nose configurations were tried plus, for Le Mans, a long-tail body that had been tested by Vaccarella at 345kph on a closed section of autostrada, but to little avail. The season was summed up by the loss of four of the 11 512Ss at Le Mans in a single incident at Maison Blanche just three hours into the race. Reine Wisell’s car was hit first by Clay Regazzoni and then Mike Parkes; Derek Bell narrowly managed to avoid contact but retired soon afterwards. Vaccarella had lasted seven laps and Ickx crashed during the night; the NART crew of Ronnie Bucknum and Sam Posey upheld 512 honour by finishing a distant fourth. The Écurie Francorchamps entry of Hugues de Fierlant and Alistair Walker followed it home in fifth.

That summer, Ferrari concluded that it needed an aerodynamic re-think, and the 512M (for Modificata) appeared at Zeltweg for October’s 1000km with Ickx/Giunti at the wheel. Its body moved away from its predecessor’s rounded curves to less attractive but more efficient slabsided surfaces. After qualifying second behind the 917 of Pedro Rodríguez and Leo Kinnunen, Ickx led comfortably in the sole works car until electrical failure ended the day. He did set the fastest lap – quicker than Rodríguez’s pole time, in fact – which proved the M’s potential.

The factory 512 was supported only by the privateer Gelo Racing entry of Georg Loos and Franz Pesch, whereas four factory-assisted 917s were fielded – two apiece from JWA and Salzburg. Each of those had also tested an additional 917 in practice. The difference in approach between Maranello and Stuttgart was clear. That same 512M, chassis 1010, went to Kyalami less than a month later for the Rand Daily Mail Nine Hours, and this time Ickx/ Giunti won by a lap from the Jo Siffert/Kurt Ahrens 917. Shortly afterwards, though, Enzo decided that all 512M development should stop, and that the 312PB should get full priority to be ready a year ahead of the new 1972 rules. The works team would therefore step back and leave the 512M to privateers.

The chassis featured here, 1024, was delivered to Scuderia Brescia Corse on 15 April 1971. Dr Alfredo Belponer entered the car for Mario Casoni and ‘Pam’ (Marsilio Pasotti) to drive. Forghieri recalls: “Belponer was a very fine manager running a tight ship, while Casoni was an excellent racer in the Italian tradition – one of the last true gentleman drivers.”

The car was run in Interserie races in 1971 with ‘Pam’ driving, and posted respectable finishes at Imola, the Norisring, Zolder and Hockenheim. Its best result came in its only World Championship outing, at Zeltweg in June, when he and Casoni finished fourth. After its competition career, 1024 was sold and briefly crossed the Atlantic, but French doctor Jean Aussenac brought it back to Europe in 1975. In ’1981, it went to his compatriot Albert Uderzo. A serious enthusiast, Uderzo was president of the French Ferrari club and for some time drove an ex-Le Mans 512BB on the road!

After a spell in the hands of American collector Charles Arnott, the 512M was bought in 1997 by Floridian Ed Davies, who campaigned it in historics racing. Ohio collector Harry Yeaggy owned it briefly in 2008-’2009 before selling it in 2010 to current owner Steven Read, who had it repainted in the Scuderia Filipinetti colours that he had dreamt of as a youth. Read has twice run the car in the Le Mans Classic, as well as at the Rolex Monterey Motorsports Reunion.

It was Read who offered me the chance to drive the car at Paul Ricard, where I was joined by Giovanni Lavaggi. The 1995 Daytona 24 Hours winner was testing the car ahead of racing it in the Dix Mille Tours du Castellet.

“The 512M is a challenging and tiring car when seeking the limit,” he explains. “Some of the balance problems could be sorted with today’s knowledge and technology, but you must bear in mind that we have to remain within fairly restrictive rules that aim to maintain the originality of the cars – and rightly so.

“Braking is the weak point. You have to brake early compared to a modern car and be very aware of, and delicate with, the pedal. Of course, on fast circuits – with the power it has and the relatively low aerodynamic drag – it reaches very respectable speeds. To lap Monza in 1 min 50 secs on grooved tyres is quite a feat!”

The driver’s seat is such a tight fit – with the fuel tank against your right thigh – that my hips are held more tightly than the harness could ever hope to squeeze my shoulders. Visibility is excellent ahead and sideways, but the rear-view mirrors are mounted a bit too far back.

Splitting the dashboard in half, the rev counter straight ahead is tantalisingly redlined at 8000rpm. From the far left, four gauges relate battery charge, water temperature, oil pressure and fuel. Among the various controls is one that flashes the headlights at pedestrian 911s, while to the right is the fuel-pump switch, turn signals and, best of all, the ignition key.

I turn it and instantly that raucous bellow erupts. At low speeds, the engine is very smooth, user friendly and surprisingly welcoming – and remains that way even when you push harder. It’s a reminder that, as per the CSI rulebook, it was supposed to be a road car. Some owners have even used a 512 on the Tour de France and its historic evocation, the Tour Auto – tiny back roads and city traffic included.

The steering is direct, precise and light, but changing gear is awkward due to the gate being tight and also quite low. Several times, I manage to select fifth instead of third, but was deliberate enough to make sure it wasn’t the other way around! It’s notchy but not heavy, a plus when you have to spend several hours at it.

The chassis inspires confidence, and within two laps I felt that I could push hard. The grip is enormous despite the treaded tyres, and you would have to be very clumsy to spin it in the dry. At high speed, it just hunkers down. Even at the end of Ricard’s Mistral Straight, it is fully stable and remains so under braking – an issue with the S that was lessened by the M’s revised shape.

Then there’s that glorious engine. With plenty of torque, it’s undemanding and will tolerate quite low revs with just the odd bumpiness, but soon its 12 lungs come on song with a mighty breath, and traffic behind simply vanishes. It offers a fabulous, progressive push all the way up to that heady redline.

This is the ideal setting in which to stretch its legs. Howling down the long Mistral through the heat haze, it does not get any better than this. The car is as balanced as can be, offering fingertip steering at 300kph as that powerplant roars away. It comes as little surprise when Read and Lavaggi win their race in it 48 hours later.

“The 512’s strength was its simplicity,” says Forghieri, “and the fact that we managed to contain costs on the project! The lack of testing worked against it, though, be it in wind tunnels or on track. We tried to head to Sicily over the winter of 1970-’71, but the weather did not allow it. The 512M was capable of beating the 917 – it did so in Austria and South Africa – but Ferrari chose to reorientate his priorities.”

Circumstances meant that the Old Man never gave the 512M its chance, which is a great pity. Ultimately, of course, the 312PB’s success validated his decision, but you wonder what the 512M could have achieved in 1971 with full works support; Le Mans was certainly within reach that year. Even so, the 512’s part in what was a truly legendary era of sports-car racing gives it all the gravitas it truly deserves.

Thanks to Peter Auto; Circuit Paul Ricard; Stand 21; Tim Samways; Steven and Peter Read

‘AFTER LITTLE TESTING, THE 512 WAS READY ONLY DAYS BEFORE THE DAYTONA 24 HOURS’

‘ICKX LAPPED FASTER THAN RODRÍGUEZ’S 917, WHICH PROVED THE 512M’S POTENTIAL’

‘THE OWNER PAINTED IT IN THE FILIPINETTI COLOURS THAT HE’D DREAMT OF AS A YOUTH’

‘ITS 12 LUNGS COME ON SONG WITH A MIGHTY BREATH, AND TRAFFIC BEHIND VANISHES’

Derek Bell

“My very first race in a sports car was in a 512 in 1970 – and at Spa, of all places. It was my first time there, which was lunacy, really. Talk about a baptism of fire, although I must have liked the place because I took pole position there the following year in the 917. The Ferrari was an Ecurie Francorchamps car and I wanted to drive for Jacques Swaters at Le Mans as well, but was called up for the factory team.

It was so disappointing. Ronnie Peterson and I were ‘also rans’ in the fourth works car. I’d envisaged that there’d be a briefing to discuss strategy for the 24 hours, but there was nothing. We were just left to it.

“On the approach to White House, I came across Reine Wisell’s 512 going slowly. I think he had oil on the ‘screen, and I wasn’t sure which way he was going to go. I went past with two wheels on the grass and looked in my mirror to see all hell breaking loose. My engine then let go on the Mulsanne, but the team hadn’t seen me go through after the accident. When I got back, they asked if I was okay because they thought I’d been caught up in it.

“I did race the Swaters car again at Kyalami, and I’ve driven 512s recently. With modern components on them, they feel great, but in period they felt like a truck compared to a 917. They just weren’t as sweet or as responsive – the 917 had that fearsome reputation, but it was a more compliant car by the time I started driving it [in 1971]. I thought it was marvellous.

“Porsche and Ferrari had very different ways of going racing, but you’ve got to remember that Ferrari also had a Formula One programme to concentrate on. That always came first.” JP

Changing rules

For the 1968 season, the CSI decided that the International Championship for Makes would be contested by Group 6 prototypes with a maximum capacity of three litres. That would include the likes of the Porsche 908, Ferrari 312P and Alfa Romeo 33/3. To bolster grids, 5-litre Group 4 sports cars would also be eligible as long as 50 examples had been built. This would enable, for example, the Ford GT40 and Ferrari 250LM to continue racing.

For 1969, however, it was announced that the Group 4 requirement would drop to only 25 cars while retaining the larger engine size – at which point Porsche targeted that category and came up with the 917. The following year, Group 4 cars were reclassified under Group 5.

For 1972, Group 5 abandoned the 5-litre, 25-car requirements and adopted the old 3-litre Group 6 regulations. That brought to the fore prototypes such as the all-conquering 312PB, Alfa Romeo Tipo 33 and Mirage M6. JP

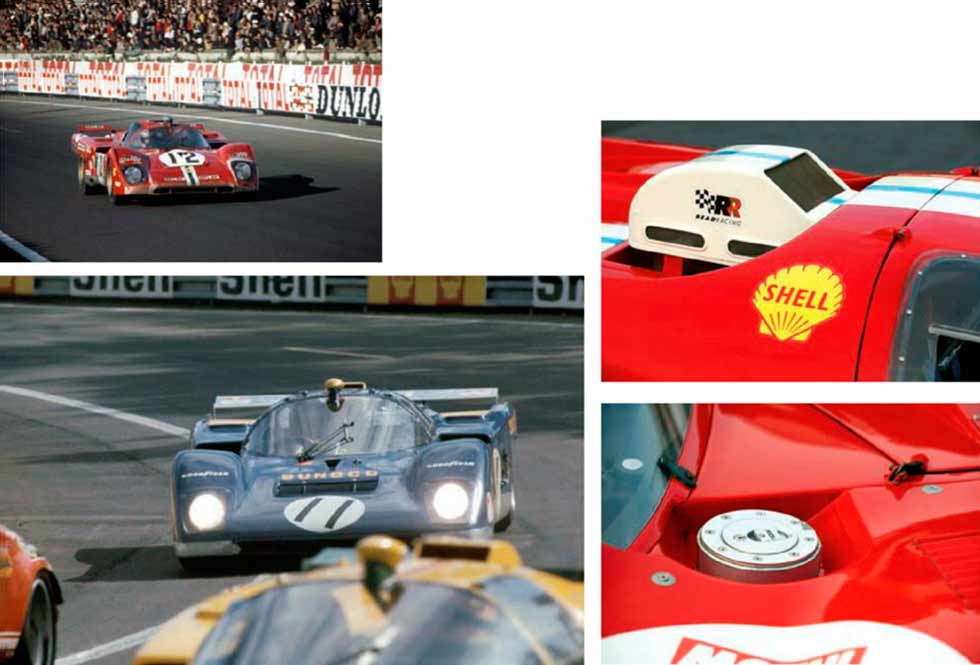

A privateer army

Although long-established Ferrari entrants such as NART (pictured right, with Posey and Adamowicz at Le Mans in 1971) ran the 512 in sports-car racing, Roger Penske produced perhaps the best-known privateer example, heavily reworking his Sunoco-backed car with Mark Donohue. The immaculately presented racer used a Traco-prepared engine, and Donohue and co-driver David Hobbs took pole position for the 1971 Daytona 24 Hours. After being hit by a 911, they went on to finish third. The pair took pole again at the Sebring 12 Hours but came home sixth, and suffered mechanical failures at both Le Mans and Watkins Glen.

Écurie Francorchamps was another long-time Ferrari customer that ran 512s, C&SC’s Alain de Cadenet sharing one with Hugues de Fierlandt at Le Mans in 1970. Escuderia Montjuich ran a similarly distinctive yellow 512 through 1970 and ’1971, the latter after having been converted to M specification.

José Juncadella and Juan Fernández finished second in the 1970 Paris 1000km, a result that Juncadella repeated on the ’1971 Tour de France with Jean-Claude Guénard and Jean-Pierre Jabouille. Chassis 1002 was later sold to Robert Horne, who in 1977 used it to set a British flying-mile record of 192mph.

With input from former factory driver Mike Parkes, Swiss team Filipinetti developed a narrowcockpit ‘512F’ with 917-type windscreen. Its Le Mans entry in 1971 ended with an early retirement, but it went on to race in that guise with subsequent owners. Porsche stalwart Herbert Müller also ran a 512M through ’1971. It was this car that Pedro Rodríguez was driving when he suffered his fatal accident in an Interserie race at the Norisring.

That year proved to be the end of an era, though. Ferrari refused to supply the 1972 312PB to private teams, telling US importer and NART boss Luigi Chinetti during a factory tour that the car’s complexity and the sheer cost of its individual components made it unfeasible. JP