Last of the breed. Aston Martin’s only pre-war single-seat racer was also the last car ever to be tested at Brooklands. We release the Monoposto onto the open road Words Ivan Ostroff. Photography Lyndon Mcneil.

Few ever have the great privilege of driving a genuine Brooklands racer. Many will remember reading legendary motor sport journalist (and former Motor Sport editor) Bill Boddy’s dazzling tales of Brooklands, never dreaming of ever driving one of those sublime machines.

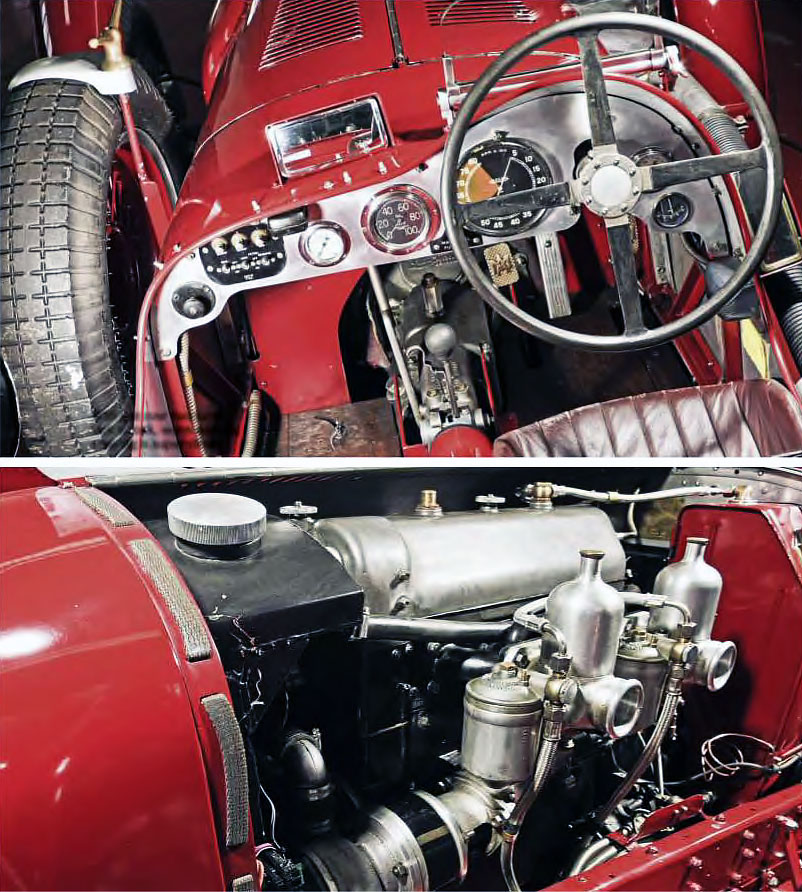

Yet here I am, in the cockpit of a blood-red 1939 Aston Martin Monoposto – the very last car to be tested at Brooklands, in fact. Low-slung, slim, purposeful and utterly business-like, it’s pure racer. The thin leather seat is surprisingly comfortable, but though you sit deep in the chassis, the heavily cutaway body sides leave the driver feeling exposed and rather vulnerable.

This is the very car that Aston Martin built to showcase what was expected to be a successful new engine design. It proved to be such a disappointment, however, that it was replaced by the engine from Dick Seaman’s old 1936 Aston Martin TT racer. And it’s that engine I’m currently sitting behind. Good grief; somebody pinch me.

I gather myself together and press the starter button. The two-litre overhead-cam four catches immediately and settles to its natural tickover – lumpy at first but soon silky-smooth. And as the exhaust slowly warms through, a deep, rhythmic thrum begins to burble from the fishtail pipe behind me. The whole car is alive with vibration now, so I grab the relatively short gearlever, shove down on the heavy clutch and engage first. The straight-cut gearbox is a big, heavy and fantastically strong non-synchromesh unit that is reputedly capable of handling up to 300bhp.

I bring up my left foot and feel the clutch engage smoothly. We’re off! The Aston’s first gear is very long, but still pulls strongly. There’s no speedometer, just a large Jaeger tachometer that reads to a dizzying 8000rpm. At what feels like about 20mph, I pull the lever back into second gear, double de-clutching as it passes through neutral. Then repeat up into third as the revs climb, and then once more into top. As you’d expect, all four ratios are stacked closely together. That long first gear means you can only accelerate as quickly as the car will allow you to drag it off the line, so you’d have to be brutal to spin those enormous wheels – something I won’t be doing in this very special car today. But this single-seater is still no slouch. It will hit 60mph in first gear in just 8.5 seconds – respectable even by today’s standards – and second gear is good for around 75mph. Third tops out at 85mph and the car’s 125mph maximum is within reach in top gear. Under hard acceleration, the exhaust note changes into a crisp bark – a bit like an eight-cylinder Bugatti, but less ripping calico, more deep, chunky burble.

The Monoposto has the biggest brakes you will find on any pre-war road car, and with 14-inch drums all round (equipped with 1¼in slave cylinders at the front, and 11⁄8in slave cylinders at the rear), you can forget all that ‘old cars can’t stop’ nonsense – these will lock up in the dry. They work via tandem master cylinders, with separate circuits front and rear. With this reassurance in mind, I start to relax and enjoy myself. I am really getting into the car now, hammering into corners and braking much later than I would in any other pre-war car.

Then a horrible moment occurs as I approach a tight T-junction. I try to move my right foot from the centre throttle to the brake pedal on the right, but the welt of my right shoe is caught. In an instant, I press my left foot hard on the clutch and knock it out of gear with my left hand, then depress the accelerator just enough to free my right foot. Within the same nano-second, I move my foot to the right and stamp hard on the brake pedal. Breathing heavily, I look down. The culprit appears to be a large nut head at the base of the column, which looks like it holds a stay in place. Heart safely returned from mouth to chest, I press on. Now aware of the danger, I try to dismiss lurid visions of horribly mangled aluminium, select first gear once again and carry on.

Obviously, there’s a limit to what you can do with a racing car on a public road, but now I’ve a proper feel of the Aston, it’s time to explore. It’s terrific fun through fast corners, the worm and peg steering controlled by a large four-spoke steering wheel that just about clears my thighs. The car’s former owner, Andy Bell, fitted an extra-long drop arm from an International model during the car’s restoration, so there are now just 1¼ turns from lock to lock. The result is steering that is rather twitchy, yet sensitive and precise. The crossply tyres may hop across the bumps, but the steering maintains regular communication, giving your instincts constant yet subtly reassuring nudges.

The Monoposto’s centre of gravity is very low, so the car always feels stable and remains predictable when it does slide. The semielliptic polished steel leaf springs must be kept well lubricated, however, so they can move freely and remain progressive. The big girder chassis feels taut and stiff but, like all Astons of the period, that live axle, combined with the heavy engine up front, dictates a certain cornering aggression to fend off tedious understeer. It’s not difficult, but you do have to steel yourself to enter and brake late to get the tail unsettled, then get straight back on the throttle and power through the corner. That’s the theory, but the wayward front end still tries to plough straight on. By unbalancing the back end further, then accelerating into a four-wheel drift, you maintain total control. You have to dial in opposite lock, of course, but the car is actually far more under control than it looks from the outside. If you’ve ever watched this car racing at Goodwood, then you will have likely seen Andy Bell indulging in a lot of lairy oppositelock slides when cornering hard through Woodcote. It isn’t a case of show-boating – the car actually seems to prefer it that way. And that’s almost certainly how the car was intended to be. In 1938 Aston Martin was looking to develop its two-litre overhead camshaft engine, but since that unit was already a stretched version of the Twenties 1.5-litre engine, it soon became clear that a brand-new design was needed. Finance was a problem, however, so Aston Martin had to come up with an alternative.

The company’s owner at the time, Gordon Sutherland, had long been impressed by the Cross Company’s two-stroke motorcycle engines, which could be revved to 9000rpm and used rotary valves in place of the usual poppet valves and springs. The thinking was that a rotary valve cylinder head should be able to handle a higher compression ratio and therefore achieve higher revs, which in turn would translate into more power. Better still, the design was lighter and more compact than most.

Aston Martin eventually secured a deal with Cross to develop and manufacture a rotary valve cylinder head under licence before mating it with Aston’s own two-litre cylinder block.

Unfortunately, subsequent testing revealed that the resultant engine produced no more power than a decent two-litre Speed Model engine, and the project was unceremoniously shelved.

While all this was going on, however, one of the 22 Aston Martin Speed Model homologation chassis that had been produced for the coming Le Mans 24-hour race had been cut, shut and fitted with narrower axles in readiness for the new engine. So in 1938 Aston Martin found itself in possession of a fine new racing chassis but no new engine to install in it. With almost no options left to Aston Martin it opted instead to rebuild a two-litre engine from Dick Seaman’s car that had seized during the 1936 TT race, and drop that in instead.

A bigger and stronger version of the standard Speed Model gearbox – itself a later development of the 1.5-litre fourspeed non-synchromesh gearbox – was used for the new car, not least because it could handle 250bhp with ease. It was also fitted with close ratios, albeit with a very long first gear. The gearbox in this car has Le Mans ratios, and in period allowed the car to hit 5000rpm and some 60mph in first gear. The only drawback was that it was very hard on the half shafts and transmission if you tried to spin up the rear wheels. So to pressure it you have to be a little slower off the line than you might have wanted.

The car was initially tested on public roads, which must have been quite a sight, since it had no body – just a crate bolted directly to the chassis upon which Sutherland could perch himself. The suspension was found to be too hard, but the car itself was extremely fast straight away.

A rudimentary body was subsequently fitted enabling both Sutherland and period Le Mans driver Charles Brackenbury to carry out further tests at Brooklands. It has been suggested that the Monoposto was created specifically for a Brooklands outer circuit record attempt. However, Andy Bell has a personal letter from Gordon Sutherland saying that the intention was always to race the car at Brooklands simply to publicise the new engine. Sadly that engine wasn’t to be.

When World War Two broke out in 1939 the Monoposto was parked up and never used again. Until, that is, David Brown bought Aston Martin in 1947, soon after which the crude works-fitted single-seater body was removed. Old archive photographs suggest that even though the car was designed for the track and therefore had no lights fitted to it, it did have wings. This was to allow it to be driven on public roads between the Feltham works and Brooklands. During restoration Andy actually discovered the holes in the back plates where the original wing stays were bolted on. Eventually David Brown passed the car on to Friary Motors, the firm that Gordon Sutherland was by then running to cater for pre-Forties Aston Martins, and in 1949 it was sold on again, this time to Gordon Gartside of Knaresborough. Gartside raced it with several different bodies (he kept damaging them) and fitted it with a pushrod engine from a DB1.

Precisely what happened to the car after that remains unclear. However, a Mr Uberg found it languishing in a Sheffield lock-up in the mid-Eighties and promptly had Aston Martin specialist Bill Smith rebuild it. It was seen on occasions at local shows, usually with Smith behind the wheel, but the Monoposto fell off the radar again for another 15 years.

When Andy Bell bought the car in 2001 it was still fitted with the old DB1 pushrod engine. He eventually traced the original ex-Dick Seaman engine (engine block number H6/711/U) to one David Taylor, who fortunately agreed to sell the engine to Andy so he could re-unite it with the car.

There then followed a comprehensive five-year rebuild, complete with Brooklands racer coachwork appropriate to the period. Amazingly, the Monoposto was still in pretty reasonable mechanical order throughout, suggesting to Andy that it had not covered many miles from new.

‘The car’s chassis and running gear are still completely original,’ he says. ‘The Monoposto bodywork is period correct and built so that it can be used on road events such as the Mille Miglia. ‘Had the Aston works continued its development, it would have been exceptionally competitive.

‘As it stands, I’m certain that it is the fastest normally aspirated pre-1940 Aston Martin in the world.’

Having had the privilege of enjoying such a memorable, evocative – and, on occasions, frankly terrifying – driving experience with this incredible machine, I’d have to agree.

Thanks to Andy Bell at Ecurie Bertelli (ecuriebertelli.com), Dick Skipworth, Jamie O’Leary at the Goodwood Revival.

‘Archive photographs suggest that the car had no lights, but did have wings fitted to allow it to be driven on public roads between the Feltham works and Brooklands’

Monoposto’s outrageous ‘fishtail’ exhaust elicits a deliciously mellifluous burble once it’s warmed through.

No speedometer in this racer: just a big-as-yourface Jaeger rev counter.

Lovely detailing includes this fuel cut-off lever.

1939 ASTON MARTIN MONOPOSTO

Engine 1950cc, inline four-cylinder, sohc, cast iron block and head, twin 1 7/8 in SU carburettors

Power and torque 136bhp @ 6000rpm; 145lb ft @ 4750rpm

Transmission Four-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

Rear axle ratio 4:1

Suspension Front: semi-elliptic leaf springs. Rear: live axle, semielliptic leaf springs. Hartford Friction dampers all round

Brakes 14in drums all round.

Steering Worm and peg

Wheels 5/8in x 18in wires

Tyres Blockley 5.60×600 all round

Length 3800mm

Width 1650m

Wheelbase 2590mm

Track 1320mm

Weight 760kg

Performance Top speed: 125mph; 0-60mph: 8.5sec

Cost new N/A

Current value £500,000

This body is one of several that have adorned this chassis Overhead cam straight four is from the 1936 TT winner.

With just over two turns lock to lock, worm and peg steering is super-direct.

OWNERSHIP REALITIES

Andy Bell has loved pre-war racing cars since his father took him to Goodwood circuit when he was just three years old. He says,‘I knew the shape of the circuit and could drive it in my mind by the time I was five.’

Years later he learned that the two Aston Martin Ulsters on the starting grid of a VSCC race at Silverstone belonged toDerekEdwards and Nick Mason, then owners of Morntane Engineering. After graduating from university in 1977, 23-year-old Andy got a job at Morntane sweeping the floor. By 1992 he had taken over the company completely.

He learned about the Monoposto in the early Eighties. ‘I knew the car still existed and where it was, but I never expected to own it. But then it came up for sale at a time when I could afford to buy it. I knew what it was as soon as I saw it; that beneath its ugly two-seater sports car body was the ex-works Brooklands Monoposto racer. I almost tore the vendor’s arm off!’

When Andy bought it in 2001 it still had the old DB1 engine. ‘I sold that engine because I knew where one of the original cylinder blocks was. The Dick Seaman car, chassis No.911, went through three different engines. I bought the original block and that’s what is in the car now.’ Ecurie Bertelli carried out the restoration, and before selling it to current owner Dick Skipworth Andy raced it at the Goodwood Revival in 2006, finishing second behind Mark Hales in Nick Mason’s Bugatti. ‘That was a great moment, the icing on the cake!’

As found in 2001, sporting a damaged body and non-original DB1 pushrod engine.

THE CAR IT SHOULD HAVE BEEN

According to former owner Andy Bell, when Alain de Cadenet tested the Aston Martin 2.0-litre Speed Model he reckoned it was superior to eight cylinder Alfas of the period – apart from the engine. ‘He said the car could have been a world-beater, since it was superior in chassis, steering, brakes and transmission. All it needed was a better engine. So, if you take that car, make it lighter and narrower and turn it into a single seater, then you have the basis for a genuinely superb racing car – which is what the Aston Martin Monoposto is.’

Low-slung and minimalist, the Aston Martin Monoposto’s beautiful body is unlike the monsters it has been fitted with over the years.