Stratos magic! Stage supercar. Driving, owning and rallying Lancia’s spectacular 1970s icon. We drive Lancia’s Dino-engined rally legend, the Stratos. A Lancia for the forest. Flat out in Turin’s World Champion. Built to dominate world rallying, the Lancia Stratos has few equals as a road car, says James Page as he goes for an exhilarating ride. Photography Tony Baker.

‘YOU QUICKLY APPRECIATE THATTHE STRATOS WAS DESIGNED FROM THE OUTSET TO BE A COMPETITION CAR’

Little Lancia handles beautifully at modest speeds, but is a handful on the limit. Right, from top: sonorous Ferrari-sourced 2.4-litre V6; stylised script; steering wheel masks upper rev range.

This is the sort of car that reminds you why you fell in love with cars. Visceral rather than cerebral, it’s the exotic poster child that conquered the world’s toughest rallies, a beguiling mix of supercar looks and pure-bred competition engineering. Throughout the 1970s, it defined its rapidly changing sport as precisely as the Mini had done the previous decade and the Audi quattro would do in the next. More than 40 years after it was introduced, the Lancia Stratos remains one of the most exhilarating ways to blow away life’s cobwebs.

Even at rest it oozes charisma. Its styling genesis can be traced to a time when Lancia was heavily in debt, recently rescued by Fiat, and in need of something spectacular. Bertone came up with just the thing at the 1970 Turin Salon in the extreme shape of the Zero concept car, which was powered by a Fulvia engine. Nuccio himself later drove the Zero to Lancia, where competitions manager Cesare Fiorio was instrumental in gaining approval to turn it into what must have seemed an unlikely rally weapon.

Marcello Gandini had been responsible for the concept, and, in early 1971, set about transforming it into a more practical prototype. By the time it was shown at Turin later that year, the distinctive Stratos outline had been set, even if the materials hadn’t. Whereas the prototype was aluminium, ‘production’ cars would be made in glassfibre. Fiorio called it: ‘A new concept of a sports car.’

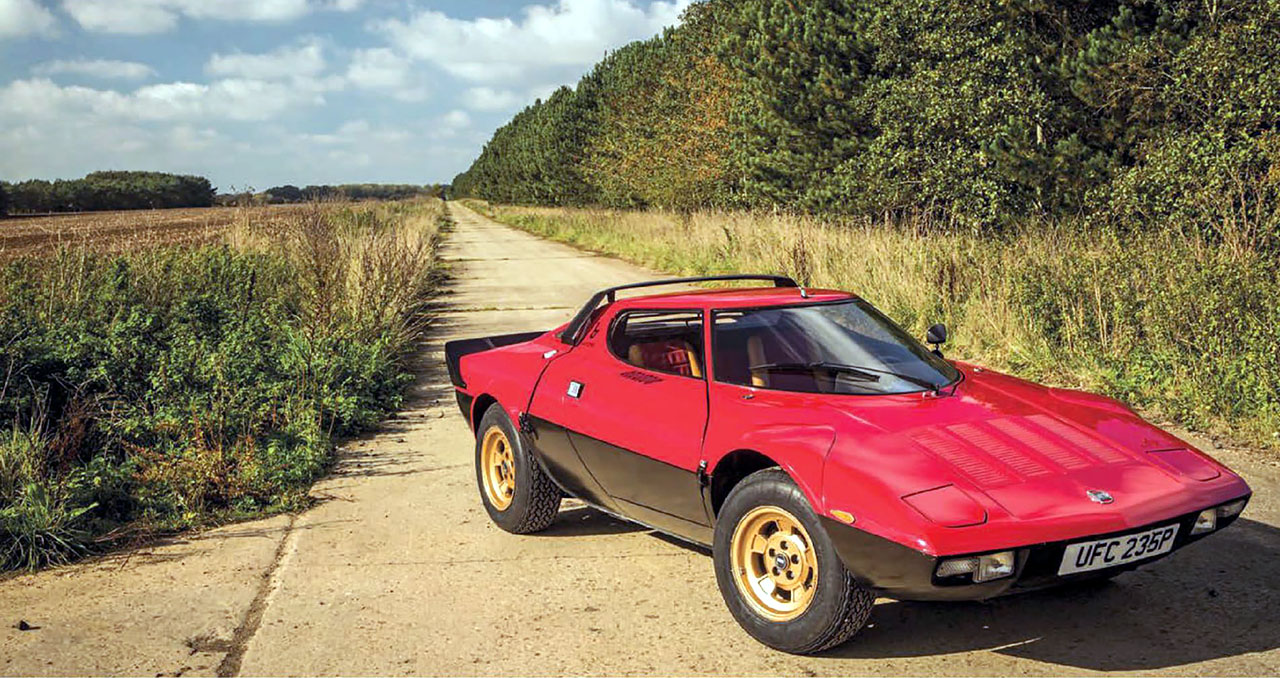

It may have been toned down somewhat from the futuristic Zero – top-opening door and all – but this is still a fabulous shape, and one of the era’s most distinctive ‘wedges’. Look at it in profile and there is barely any change in angle as you follow the line of the front panel all the way up the big, curved windscreen. The hefty wheelarches punctuate the flow, and you quickly appreciate that the Stratos is a car of extremes: wide but very short; a heavily tapered bottom half; generous at waist level but tight around the pinched roofline.

You also quickly appreciate that it was planned from the outset to be a competition car. The front and rear clamshell panels swing out of the way to reveal the central steel tub plus the front and rear sub-structures that house easily accessible mechanical components – essential if service crews were to carry out swift remedial work between stages. There are few of the compromises often found in a design that was first and foremost a road car.

Development continued apace through 1972, with Gian Paolo Dallara and Mike Parkes helping to engineer the chassis. To improve durability and usability on rough roads, for example, the rear suspension was changed from double wishbones (as used on the front end) to MacPherson struts. Such was the rate of progress that the car – not yet homologated for Group 4, but able to run in certain events as a prototype – made its debut on the 1972 Tour de Corse, Sandro Munari and Mario Mannucci unfortunately being forced to retire with suspension failure.

At that time, the homologation requirements stipulated that 500 examples needed to be built within a 12-month period, and Stratos approval was finally granted in October 1974. Not that anyone has ever claimed that Lancia managed to build all 500 and, in any case, Group 4 requirements were later revised downwards to 400 cars. Records suggest that, at most, 498 were finished – even that is thought by some to be wildly optimistic – with the factory selling them as late as 1978, and specialists building them up from component form into 1979.

The featured example is chassis 1595, a roadgoing Stradale variant that was built in 1976 and which was originally painted green. Its second keeper was reputedly a close friend of Enzo Ferrari and, by the time that its third and current owner bought it in 1986, it had been resprayed its current red over black. Much used and enjoyed over the years, it wears its patina with pride. Somehow, a Stratos is one of those cars that doesn’t look quite right when it’s pristine.

Even in Stradale spec, there’s no getting away from its sole purpose in life. The long doors weigh only 6kg each, are finished with a hard panel rather than soft trim, and feature deep scallops that were designed to hold crash helmets. Don’t expect to find a window-winder, either – the glass is raised and lowered by means of a simple wheel that you just slide up and down within its channel.

The pedals are slightly offset to the centre of the car, and there’s the odd sensation of having acres of elbow room but almost no headroom – especially laterally. The relationship between instrument pod and steering wheel also means that you can’t see the upper reaches of the rev counter – the yellow section on which starts at 7000rpm, with the redline at 8000rpm.

The famous Dino V6 engine had always been first choice, but until Ferrari agreed to supply it in late 1972, Lancia made various contingency plans, including its own twin-cam ‘four’ and even Maserati’s V6 or V8. In the end, though, Maranello’s unit was installed transversely and in such a way that access to the drop-gears was good enough to allow for quick ratio changes.

It is inconceivable now to consider the Stratos having anything other than this brilliant powerplant. In Stradale spec, it gives 190bhp – a 24-valve head was developed for the competition cars, upping power to 300bhp – which doesn’t sound like a huge amount, but then it’s pushing something that weighs well under 1000kg.

Suffice to say that it’s plenty, and it sounds absolutely glorious, a low-rev growl turning into a bark as it zips through its range. If you haven’t already been seduced by the looks, you surely will be by the noise – as intoxicating as anything that has ever resonated through a forest stage, and no doubt a welcome antidote to the masses of Escort four-pots in period.

The five-speed gearbox is slightly recalcitrant until the oil’s warm – particularly when you’re trying to involve second gear in proceedings – and the brakes seem a bit wooden, but nonetheless a Stratos has a feel unlike anything else. That is thanks in part to a driving position that makes it feel as if you’re positioned at the head of an arrow, and also to its combination of short wheelbase and wide track – the Stratos is fully 19in shorter than a Dino, with a wheelbase that is 6in less, but it’s about the same width.

In the name of period correctness, the featured car is fitted with its original 14in Campagnolo magnesium wheels on 205/70 VR14 Michelin XWX tyres. Its current owner generally runs it on modern Compomotive alloys with Yokohama rubber, a combination that makes it more user-friendly on the road. Even the Stradale features fully adjustable suspension and, at modest speeds, it will turn on a sixpence with no fuss, and no inertia. With great visibility through the wraparound windscreen, it is supremely easy to place through corners, and the light steering very soon inspires the sort of confidence that makes you feel as if you could do absolutely anything with it.

Which is deceptive, of course, because – with more than 60% of the weight resting over the rear wheels – in extremis it will switch from understeer to oversteer in the blink of an eye. Peter Newton sat alongside Tom Pryce ahead of the F1 star’s one-off outing on the 1975 Tour of Epynt. ‘The Stratos is not an easy car to drive near its limits on loose surfaces,’ he wrote in Autosport magazine, ‘and anyone who has watched [Björn] Waldegård grappling with his Alitalia car through stages, hands twirling mightily at the wheel, will know that.’ It may have needed the talent of a Waldegård or a Munari to fully unlock its potential, but once Lancia had given the Stratos the reliability to match its obvious speed, it had a world-beater on its hands. A versatile one, too – Munari and Jean-Claude Andruet drove one to second place on the 1973 Targa Florio, before the former linked up with Mario Mannucci to win that year’s Tour de France.

It claimed three World Rally Championships – in 1974, 1975 and 1976 – before a certain degree of in-house politics meant that parent company Fiat switched its attention from Lancia’s purpose-built rally car to its own 131 Abarth. The Stratos kept winning in the hands of privateers, though. Bernard Darniche claimed the model’s fourth Rallye Monte-Carlo in 1979, and the Tour de Corse as late as 1981. In all, it won 82 international rallies.

As a road car, though, the Stratos was a commercial failure – it didn’t comply with American regulations, so couldn’t be sold there or even in certain European markets. In Italy, it was offered at roughly the same price as the Dino, but to a certain extent Lancia didn’t care about that. It was concerned only with rally success – creating a money-spinning road car wasn’t high on its agenda beyond helping with homologation. Now, of course, all variants have become hugely desirable.

“As with a lot of cars, people want correct, original examples that haven’t been messed around with,” says specialist William I’Anson. “Lots were simply tarted up when they weren’t worth the money. They hovered around Dino values – or perhaps just ahead of that – for a long time, but this is a proper homologation special and one of the most iconic rally cars.

“The Stratos really marked the start of professional stage rallying – it launched Lancia in that world and the company went on to dominate it. They should be worth more, in my opinion. They’re much rarer than a Dino, for a start, and I think that they’re still undervalued.

“When you drive one, you can see why it was so successful. It’s a real enthusiast’s car, and you have to concentrate to get the best out of it.” The rewards on offer justify that concentration, that involvement. To be honest, it is hard to think of driving a Stratos gently. Each straight bit of road becomes an excuse to listen to that glorious exhaust note one more time.

Let’s hope that the recent increase in values – a Stradale sold for £308,000 at RM Sotheby’s recent London sale – doesn’t lead to more examples being stored away in collections. If ever there was a car that is begging to be used and enjoyed, it is the Lancia Stratos.

Thanks to William I’Anson, who is selling the featured car: williamianson.com; 01285 831488; Paul Lawrence; Jane Houghton

‘EACH STRAIGHT BIT OF ROAD BECOMES AN EXCUSE TO HEAR THAT GLORIOUS EXHAUST NOTE’

Clamshell panels offer good access to mechanical components. Below, l-r: second owner had the car painted two-tone; original toolkit nestles in spare.

THE SPECIALIST Martin Cliffe

“The Stratos was a small-volume car that was never developed in the way that, for example, a Ford would have been,” says Martin Cliffe of Lancia specialist Omicron (www.omicron.uk.com; 01508 570351), himself a Stratos owner since 1984. “In many ways, they were designed as cheaply and quickly as possible so Lancia could go rallying, and while that means that the reliability often doesn’t compare to that of a mass-market car, it does mean they’re relatively simple – a competent amateur could look after it at home. Everything’s quite accessible, with the exception of the alternator, which is hidden away beneath the front bank of exhausts and is an absolute so-and-so to get to.

“The brakes are a weak point on Stradales. The competition cars had 15in wheels rather than 14in, so they could have proper Lockheed brakes rather than the ATE ones. In terms of the V6 engine, it’s pretty much all Ferrari Dino apart from the carburettors and water hoses – just detail differences, really.

“Even so, some components are getting more and more difficult to find, and companies have begun to remanufacture them. The problem is, there are so few cars around – and so few that are actually covering any sort of mileage these days because of their value – that it rarely makes economic sense to make new parts or for us to carry a large stock of them.”

Clockwise, from main: fabulously compact wedge shape – note the correct 14in Campagnolo wheels with Michelin XWX tyres. Below, l-r: Gandini styled the car while at Bertone; minimalist interior.

‘ONCE THE STRATOS WAS MADE RELIABLE, LANCIA HAD A WORLDBEATER ON ITS HANDS’

THE RALLY DRIVER Steve Perez

“It started life as a Stradale,” says Perez of his Stratos (below), “but I bought it about 12 years ago in Group 4 spec. With the short wheelbase, it’s a difficult car to drive. It’s very nervous, and always wants to bite you – especially over bumps. It’s much happier on tarmac. I’ve got a quattro, too, and that’s even harder because everything’s happening so much faster. The Stratos at least changes direction well – if a stage is tight and twisty, we’ll be okay.

“We’ve had all sorts of engine and gearbox problems – it can select two gears at once and get jammed – and it’s getting harder to find parts for it. Most things have to be manufactured.

“It’s such an iconic car, though, and nothing sounds quite like it. When we turn up in a service area, the attention we get is such that you’d think Sébastien Loeb had just arrived. Getting it to the finish of any rally is an achievement, but it’s great to line up at the start of a stage and be the lone Stratos among 20 Escorts!”

THE ENTHUSIAST Ian Fraser

Motoring journalist Ian Fraser bought a Stratos “when they were cheap” in the 1980s. “It was such an exciting looking car – I was just captivated by it. You couldn’t buy them in the UK so I put out some feelers and one turned up in Germany. I drove it back, arriving in Calais late at night and parking it on the street outside the hotel. Not ideal, but it got left alone.

“When I first drove it, I remember thinking: ‘I’ve got to be careful here.’ Still, the best way to steer it was via the throttle rather than the wheel, and it would do 140mph – as promised! I got all the UK paperwork done, which was complicated, and later used it for a long trip to the Alps. Contrary to expectations, it was a beautiful touring car, with little wind noise and a surprising amount of room. I took my late friend ‘Steady’ Barker as a co-driver and general raconteur, and he loved it. I actually had to fly back to the UK for a wedding at one point, left him with the car, then flew back out to meet him.

“Returning through France, the clutch hydraulics went. We stopped at a Fiat dealership, and he got us back on the road in less than two hours! It was generally very reliable, but it wasn’t the sort of package that made for a daily driver.

“It was just a magic car, with terrific performance and that lovely Dino engine. I sold it about four years ago, and that was one of my great motoring mistakes.”