F1 should be contesting its seventh hybrid season. Instead we’ve time to examine how these power units work, and how they’ve evolved. By Craig Scarborough and Ben Miller.

Rewind to Jerez, and the first pre-season test of the 2014 Formula 1 season. Mercedes and Ferrari are tentatively chalking up laps, gleaning priceless information about their complex new power units with every mile. Meanwhile Red Bull and Renault – reigning champions, no less – are living through some kind of very public waking nightmare. Over the four-day test Sebastian Vettel manages 11 laps; team-mate Daniel Ricciardo just nine. The car is woefully unreliable, with vibration hindering the Renault unit’s ability to recover energy while blinding heat wreaks havoc within the car’s shrinkwrapped bodywork. Oh dear.

In 2020, with F1 now in its seventh hybrid season, the power units are now some 120bhp more powerful (up from 900bhp to over 1000bhp), more efficient (thermal efficiency is up from 44 per cent to more than 50 per cent), more reliable (three units per driver, season) and more driveable. They also burn a third less fuel than the last of the naturally-aspirated V8s.

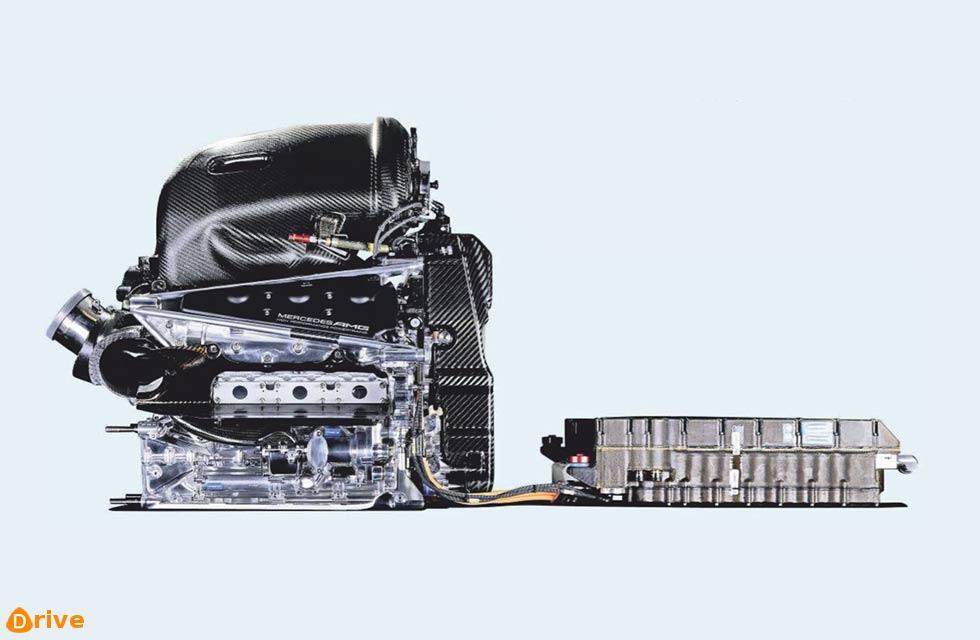

The engine element is a direct-injection, turbocharged (with a 12,000rpm rev limit) 1600cc V6. Exotic fuels are banned, the engine’s vee angle and mounting points are fixed, and a fuel-flow restriction rules out sky-high revs or huge boost. Electrical elements include the lithium-ion battery, the power electronics and two motor/generators: one geared to the engine’s crankshaft (to power the rear axle and to convert kinetic energy into charge); and another on the turbo capable of charging the battery or spinning the turbo, to help mitigate lag. As well as this complexity there’s an incredible level of heat: the battery’s oil-cooled; the energy recovery systems and control electronics liquid-cooled. So it’s little wonder those early Renault units cooked themselves on an hourly basis back at Jerez. But time, money and effort have since been deployed tirelessly, boosting power, reliability and efficiency.

Mercedes-AMG’s domination of the hybrid era is built on a couple of creative engineering solutions. The first was to split the turbo. Where rivals engineered their turbos traditionally, with the turbine and compressor in a single unit, AMG separated the two, linked by a shaft between the V6’s cylinder banks. Why? Because turbines are hot and compressors more powerful when they’re cool, so the two are happier apart. Another was a pre-ignition chamber in each cylinder to cluster precious fuel in a pocket of rich mixture around the spark plug. Once ignited, the flame front is carefully directed into the main combustion chamber, where it ignites even a weak mixture.

Ferrari’s hybrid competitiveness took a leap forward in 2015, and central to its lack of performance in 2014 was a missed trick when it came to the size of the turbo. Keen to not hurt engine horsepower with excessive back pressure, Ferrari went for a modestly sized turbo. Honda did the same, chasing a tiny, low-drag overall package. By contrast AMG went for a monster, reasoning that the excess boost (which would normally be lost via a wastegate) could instead be used to generate a glut of extra electrical power via the motor/generator unit on the turbo. For while the rules placed a limit on the amount of regeneration permitted by the crankshaft motor/generator, there is no such limit on power scavenged by the turbo unit.

Impressive but irrelevant technology? Hardly. The next-generation performance hybrids are upon us, and the likes of Ferrari (with its SF90) and AMG (with the hybrid GT 4-Door and the One hypercar) won’t have forgotten all that F1 has – very expensively – taught them.

INSIDE AN F1 V6 HYBRID

ENGINE

The 1600cc V6’s architecture is restricted but gains can be made in the design of the combustion chambers. Variablelength intake plenums legal now.

REGENERATION

Early on, some teams wrongly assumed that engine horsepower would still be king. In truth clever energy regeneration and deployment is what wins races.

CONTROVERSY

Having created the most powerful power unit on the grid, Ferrari’s faced accusations of rulebending, particularly the deliberate burning of engine oil to boost power.

AMG’s F1 tooling is producing breathing devices.