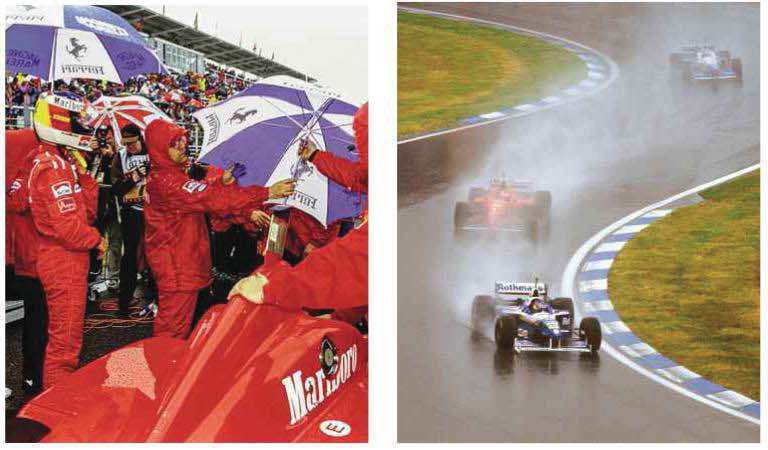

Greatest Races the Reign in Spain. Greatest Races Schumey in the rain in Spain. Michael Schumacher’s win in the 1996 Spanish GP was simply one of the greatest ever. In atrocious conditions at the 1996 Spanish GP in Barcelona, Michael Schumacher was all-conquering. Words Andrew Frankel. Photography LAT.

GREATEST RACES 1996 SPANISH GRAND PRIX / SCHUMACHER ‘When it rains, the true masters step forward’

Sometimes the meaning of words changes according to who is saying them. Take this quote about Michael Schumacher’s performance in the 1996 Spanish Grand Prix as an example: ‘That was not a race. That was a demonstration of brilliance. The man is in a class of his own. There is no-one in the world anywhere near him. I do not think there has ever been a driver who is so far clear of the field in terms of ability. It was one of the most fantastic demonstrations of skill I have ever seen, up there with Senna and Fangio.’

Had they been uttered by Schumacher’s manager, Willi Weber, or spokesperson Sabine Kehm we might not take them quite as seriously as their apparent gravity suggests. Spoken by Stirling Moss, possibly the only other person alive guaranteed also to figure in anyone’s list of greatest racing drivers of all time, they mean something else altogether. And when you look more closely at what Schumacher achieved in Barcelona that day, it’s not hard to see why.

‘Ferrari was in the middle of its longest fallow spell since the early ’50s’

But first a little context. By the time Michael Schumacher joined the Scuderia for the start of the 1996 season, he was already a double world champion, the man who took the Benetton team and by means both fair and, on occasion, foul, vanquished the seemingly insuperable Williams team. By contrast, Ferrari was in the middle of its longest fallow period since the Formula 1 world championship had started in 1950. Not since 1979, 17 long seasons ago, had one of its drivers carried off F1’s ultimate prize.

‘There is no greater leveller than rain. When it rains, the true masters always step forward’

But a championship title is a child of many parents, and it would not be until the turn of the century that Ferrari was able to put together the team including Rory Byrne and Ross Brawn that was required to consummate the deal. But a single race” That was different. Just occasionally circumstances might contrive to magic a victory out of, well, almost nowhere at all.

To understand the enormity of what Schumacher achieved that day, we need also to understand where Ferrari lay relative to the opposition at the time. In comparison to the rampant Williams team, that was precisely nowhere. Yes, he did qualify in third place behind the Didcot pairing of Damon Hill and Jacques Villeneuve, but that said everything about the man behind the wheel and the fact that, even by his own admission, he did a perfect qualifying lap – and very little about the truculent, aerodynamically inexact Ferrari F310 at his disposal. Even so, he was still over a second off Hill’s pole pace. Eddie Irvine’s sixth place on the grid, achieved after extensive testing at the track and behind both Benetton drivers, was a far more accurate estimation of the Ferrari’s real pace.

‘You didn’t need a stopwatch to tell Schumacher was going faster than anyone else’

Such speed as the F310 did possess came, in traditional Ferrari fashion, courtesy of its engine. With rules reducing engine capacity to just 3 litres, Ferrari finally abandoned its beloved V12s that – turbo era aside – had served in its cars since, ironically enough, the 3-litre formula was first introduced in 1966. The new V10 was seen to offer similar power to a V12 with better torque and fuel consumption, thanks in part to lower frictional losses, and with the bonus of a shorter, stiffer construction.

Schumacher, fresh from a Benetton powered by a Renault V10 believed to be the best engine on the grid, had no complaints about his new car’s power at all. By contrast, Irvine had rather greater grounds, not least because by the end of the season he would have retired from ten of its 16 rounds, including a stretch of eight on the trot, starting in Spain.

As for the car, the Ulsterman dismissed it as ‘almost undriveable’ while even its creator, John Barnard, conceded that it was not one of his better designs. Indeed it and its F310B update would be the last cars he’d design from his Guildford Technical Office, and the last Ferraris to date not designed and engineered in Maranello. Byrne and Brawn replaced Barnard in 1997 and set out on a path that would deliver five Drivers’ and six Constructors’ World Championships between 1999 and 2004.

But, back in Spain in 1996, Schumacher was so unsure of his chariot that in practice he tested two entirely different set-ups, not in the least sure of which one represented the right way to go. It was already looking like it might be a very long weekend.

‘By the end of the second lap, six cars, almost a third of the field, had crashed or spun off into retirement’

And then the drivers woke up on Sunday morning, looked out of their hotel windows and were greeted by an entirely different world to that in which they had qualified the day before. It wasn’t just raining; it had been raining steadily and heavily for hours. Some would no doubt have gone happily back to bed but not, I suspect, Michael Schumacher. Always the hardest working driver in Formula 1, he will have bounced into the pits that morning and greeted his engineers with something of a spring in his step. In racing there is no greater leveller than rain, and, when it rains, the true masters always step forward.

Moss was uncatchable in the rain, as was Jim Clark. At the 1968 German Grand Prix, held in deluge conditions, Jackie Stewart won the race and was out of the car and spectating before the next car came by four minutes later. Ayrton Senna was in a league of his own when he won his first Grand Prix at a wet Estoril in 1985 and again when he won his last at Donington in 1993. In similar conditions at the fast and challenging Circuit de Catalunya, Schumacher would have reckoned that his talent would make up for the manifest shortcomings of his car. If he could just wrestle his way through at the start and get the Williams pair behind him, he’d have backed himself to keep them there.

It was Helmuth von Moltke, a 19th-century head of the Prussian army, who said ‘No battle plan ever survives first contact with the enemy’, and so it proved at Barcelona. Had the race been held today it would have been started behind a safety car or not at all, but back then, while there was talk of a rolling start, it came to nothing and all the cars lined up as usual. For Ferrari, the good news was that Hill was indeed slow away from pole, the bad that Schumacher, troubled by a sticky clutch, was even slower. Passed by both Benettons at the end of the first lap, he was down in seventh place.

To give you some idea of the conditions, by the end of the second lap, six cars, almost a third of the field, had crashed or spun off into retirement, including Irvine. Visibility was so bad that, to this day, David Coulthard is not sure whom he tangled with to end his race.

The only person who could see was Hill’s team-mate, Jacques Villeneuve, and in a car designed by Adrian Newey on a circuit now legendary for the advantages it confers on cars with effective aerodynamics, he should have scampered away But he didn’t. And Schumacher wasn’t letting his early setback put him off his stride.

He was further helped by Hill, who appeared completely unable to cope with the conditions and spun three times in seven laps, finally ending in the wall and out of the race. By the time of the first of these spins, Schumacher was already lining up Gerhard Berger’s Benetton for third place; five laps later he was past Jean Alesi’s sister car for second, and three after that he displaced Villeneuve from the lead. Simple as that.

Those who saw him thereafter witnessed a man in a race of his own. As if to atone for uncharacteristically binning his Ferrari at the previous round in Monaco, it seemed as though Schumacher had challenged himself not merely to show the world that he was the best driver in the business, but by a margin that not even the most ardent fan of Williams, Hill or Villeneuve could contest.

As cars and drivers succumbed to water- induced failures – half the field was hors de combatbefore one third of the race was complete – you could see those who remained go into survival mode. Just get to the finish, they thought, and there would be points to have. And they were right even in those days when points were awarded only to the top six finishers, because that’s how many made it to the end.

Schumacher took a somewhat different view. Even then, relative speed at the level of FI was hard to see because a car going down the road at 180mph looks much the same as one doing the same at 170mph, but you didn’t need a stopwatch to tell Schumacher was going faster than anyone else: you just needed eyes. He was visibly faster than anyone else. Nor was this a Prost-like exhibition of precision driving; indeed at times it looked as though someone of finest Scandinavian rallying stock had slipped behind the wheel of the F310.

I’ve forgotten almost every Grand Prix I’ve watched in the intervening 22 years, but not this one. This was car control of a kind I’d not seen in F1 since the days before downforce made it more efficient to drive without a significant yaw angle. Yet here was Schumacher throwing this undeveloped, aerodynamically flawed Ferrari around like it was a Mk2 Escort. In F1, gaps are measured in tenths, hundreds and occasionally thousandths of a second, but not today On certain laps he was three entire seconds quicker than anyone else on the track.

‘The car was clearly not firing on all ten, and yet still the gap grew’

But that’s not what was most staggering about what Michael Schumacher did that day It is that he did it with a car that was not only uncooperative, but sick as well. Early on in the race, his engine had sounded a little rough, but by half distance it was clearly not firing on all ten, and maybe not even nine. And yet still the gap grew He pulled in for his second and final pit-stop on the 42nd of 64 laps; these stops were far slower affairs than today thanks to refuelling requirements, and yet even when he rejoined the next best car was still over a minute behind the ailing Ferrari.

Only then, and with his point proven in the most dramatic and unambiguous way, did the World Champion ease off the throttle, cut back on engine revs and cruise to the finish. Even then he was still 45 seconds ahead of Alesi and 48 seconds ahead of Villeneuve. Everyone else had been lapped.

Michael Schumacher would win twice more that season, memorably at Spa and again at Monza in front of the adoring tifosi, dragging Ferrari up to second place in the Constructors’ Championship in a car that probably had no business being anywhere near the sharp end of such a competition.

But when I look back at the myriad victories and titles Schumacher would deliver, Spain in 1996 is always the one I remember most fondly Not because it was his first for Ferrari – though it was – and not even because it was his best, because I don’t feel in a position to make such a judgement. It’s a race I love to think about because it’s the one that convinced me that Michael Schumacher was not the pantomime villain of F1 the Damon-loving British press had made him out to be. Yes, he had flaws and some of his driving while at Benetton was indefensible. But at Barcelona that day I saw an F1 car being driven in a way I’d not seen since Senna’s opening lap at Donington three years earlier.

But this demonstration lasted an entire race and, by the end of it, I was as convinced as I remain today that Michael Schumacher was in a league of his own, the best driver of the post-Senna generation. To this day I have seen nothing from either Lewis Hamilton or Sebastian Vettel – brilliant though both undoubtedly are – to make me modify that view.