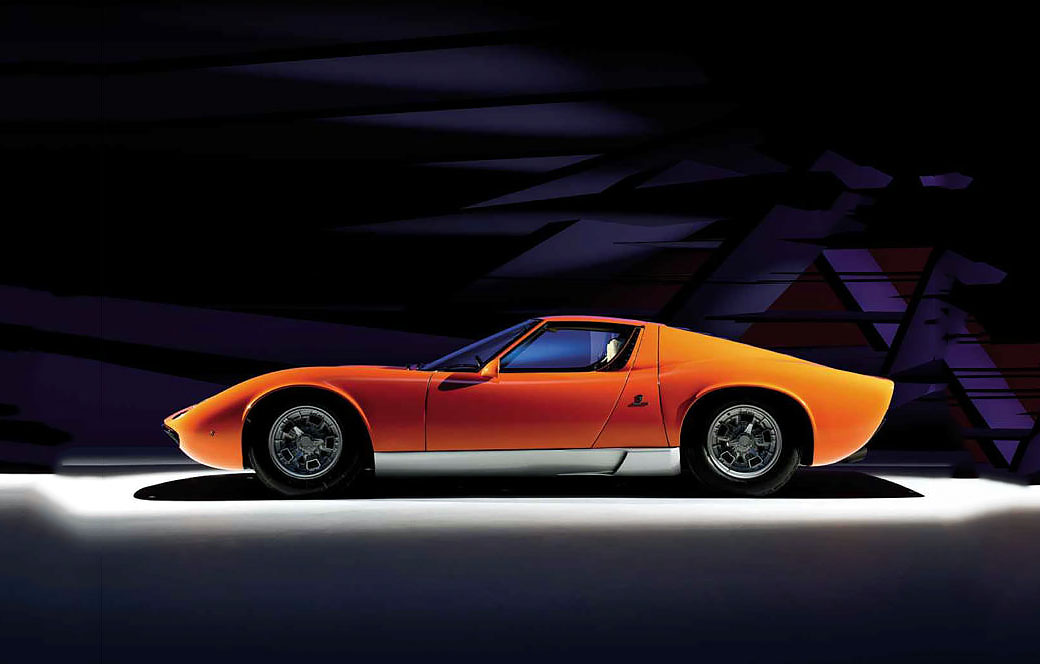

The Italian Job Mura – Could this be that long-lost car? Read the evidence. Is this the real thing. For decades, the identity of the Lamborghini Miura used in one of the most famous opening scenes in movie history has remained unknown. Now the mystery may have been solved. Words Mark Dixon. Photography Paul Harmer.

It’s one of the most evocative openings to a movie ever made. A bright orange Lamborghini spears across an elegant viaduct in the Italian Alps. We see its driver – a typically dapper silver fox, wearing sunglasses and smoking a cigarette – deftly hurling it around the mountain hairpins, to the soundtrack of Matt Monro crooning On Days Like These. The car roars into a tunnel… and then there’s a horrendous crash, which, we soon discover, is because the Mafia have hidden a huge bulldozer inside the tunnel. As the crumpled, smoking remains of the Lamborghini are pushed down the mountainside, a Mafioso throws a wreath after it, with bitter irony.

The sequence is familiar to tens of millions of Britons, and millions more across the globe, after countless Christmas-time and holiday repeats on television since The Italian Job was released in 1969. Many people adore the film; some are less enthusiastic; a few find it excruciating. Certainly it’s hard to think of another movie with a cast list so off-the-wall that it ranges from Noel Coward to Benny Hill via Michael Caine.

Love it or loathe it, you can’t forget that opening scene. The idea of smashing up one of the most beautiful cars ever made will cause Drive-My readers physical pain – and the Miura was very much the ultimate supercar when The Italian Job was filmed during the summer of 1968. Amazingly, though, the actual car being driven in that sequence has never been identified. Until now.

Iain Tyrrell, proprietor of Cheshire Classic Cars and a Lamborghini specialist for some 30 years, acquired what he believes is The Italian Job Miura in 2014. ‘A friend of mine, Keith Ashworth, and I bought the car as a joint project. We had a very limited window of opportunity, and the process was all very James Bond-ish: I was escorted down to a secret underground car park in Paris to view it.

‘Although we bought the car in France, it has been in Italy for almost all its life, and I’m convinced that the 19,000 km recorded on the odometer are genuine,’ Iain continues. The body had a respray just a few years ago but otherwise it’s not had major restoration. The engine block was replaced in the 2000s because it had cracked – we still have it – but the owner was extremely well connected with the factory and managed to obtain the last brand-new Miura SV block, which is in the car now.

The interior trim in early P400 Miuras was of poor quality, and certainly not built to last decades. In this car it’s all consistent and factory-spec, including every bit of carpet, and shows very little wear. The electrical equipment, underbody finishes – all the things that naturally age – are time warp undisturbed. In fact, looking at the condition of the dashtop, I would say that the car has been garaged for most of its life, because it has not been damaged by exposure to sunlight.’

That dashtop is a crucial piece of evidence in the case for this being the car from The Italian Job, and we’ll come to it later. It has to be said that there are a number of dissenters who claim that this is not the movie car, and Drive-My cannot definitively say that it is. But read on, examine the evidence, and make up your own mind. Whatever the verdict, it’s a fascinating story.

Exactly what went on during the few days spent filming the opening scenes of The Italian Job has never been clear. Even the 2001 book The Making Of The Italian Job, which contains interviews from numerous people associated with the film, is sketchy on this part. The main film crew was shooting elsewhere, so the job was delegated to a second unit consisting of a skeleton crew directed by John Harris. Sadly, Harris died of cancer in August 2012, after a 53-year career in films.

What is certain is that two different Miuras were used for filming. The first – possibly chassis 3586 – appears in all the driving shots. The second, whose identity is not known, was a wreck that had reputedly been returned to the factory after an accident in the Middle East. Minus engine and transmission, it was hastily repainted Arancio Miura (orange) – or so the story goes – to match the driving car, and it was then impaled on the bulldozer’s shovel before being pushed over the side of the mountain.

Facing page While Miura no 3586 is remarkably original, thanks to its low mileage, it has had a factory replacement engine block within the last decade. Otherwise the car is very much as it left the Lamborghini factory in July 1968.

The wrecked Miura disappeared straight after filming – quite literally. Special effects man Ken Morris was tasked with retrieving it from the bottom of the river gorge, but recalled later: ‘I went to rescue it, as you always have to get these vehicles back… but I couldn’t find it! It had disappeared by the next day. I went down there many times as, after all, it was only a small river. So somebody must have seen us throw this Lamborghini down, and retrieved it during the night.’

The driving sequences were filmed at a number of locations in the Grand St Bernard Pass in north-west Italy, above the town of Aosta – there’s a fantastically detailed analysis on the website, which gives plenty of hints and tips if you feel like making your own pilgrimage. In the very first shot, the Miura is crossing a viaduct that leads to the Grand St Bernard tunnel linking Italy and Switzerland. In fact, the car is heading away from the tunnel, as if returning to Italy.

Right. The ‘wrecked’ Miura is about to be pushed over the side of the mountain, watched by Mafia boss Altabani (Raf Vallone). In reality this was the shell of a previously crashed Miura, whose identity is still unknown. It vanished within hours of this scene being filmed.

That’s probably coincidental – the film-makers would have chosen the shot because of the way the sunlight was falling – but it fits nicely with the plotline. The Miura’s driver is a criminal called Roger Beckerman (played by Rossano Brazzi), who is planning an elaborate gold heist from under the noses of the Mafia. Suspecting that he may not survive, he has secretly recorded a piece-to-camera outlining his plot, which is then picked up by British thief Charlie Croker (Michael Caine). He takes it to crimelord Mr Bridger (Noel Coward), to secure the funds needed to stage an audacious raid in the heart of Turin.

So what do we know about Lamborghini Miura 3586, and why does it have a claim to be a movie star?

Enrico Maffeo is in charge of Lamborghini’s heritage department, and at Drive-My’s request he retrieved all the paperwork that’s currently on file about 3586. He points out, however, that the archive is in the process of being reorganised and it’s possible that more information may yet turn up.

The car’s build sheet records that 3586 was originally specified with red paint and black leather interior. The car was road-tested on 18 June 1968 and it was delivered on 2 July to the Ravenna-based distributor Zani.

This immediately raises a query, because the film car is clearly orange. Moreover, the headrests and transverse padded bar behind the seats, which are visible during the in-car shots of Rossano Brazzi driving, are trimmed in white leather.

However, Sig Maffeo confirms that on the build sheet, ‘black vinyl’ has been crossed out and replaced with ‘white leather’. More significantly, there is an additional piece of paper with the build sheet from Lamborghini’s sales department – common practice when a customer requested particular modifications or features for their car. On this paper, the specification for 3586 is amended to Arancio Miura (orange) paint, and white leather seats and headrests.

So, there is official confirmation that Miura 3586 was outshopped in orange paint with white interior. That’s not a unique combination but it’s certainly not common: a Lamborghini insider from the early ’70s, who did not want to be named, told Drive-My that the factory discouraged customers from ordering white leather because they had problems with the finish becoming ‘chalky’.

According to Olivier Nameche, president of the Lamborghini Club Belgium – who has been researching an encyclopaedia about Lamborghini for many years – only two other cars were produced with a white interior in this timeframe. Car no 3396 (red with white interior) was delivered on 2 April 1968, while no 3757 (black with white interior) left the factory on 13 September 1968.

This is where dates become critical. According to two former Italian Job crew members, David Wynn- Jones – who, as a young camera assistant, was attached to the second unit filming the opening scenes – and actor David Salamone (who played Mini driver ‘Dominic’) filming in the Great St Bernard Pass took place in the last days of June 1968. (The pass is open only from June to September, and in the movie there’s still snow lying on the ground.) The build sheet of 3568 records that it was delivered on 2 July 1968; just enough time for a fast run back to the factory and a final valet?

Amazingly, we know exactly who delivered the orange Miura to the film-makers in that summer of 1968. ‘It was hot!’ recalls Enzo Moruzzi, who at the time was working in Lamborghini’s sales department, escorting customers on test drives and delivering cars. Moruzzi had a long career at Lamborghini, becoming head of sales in 1993, and he well remembers being on set during filming. ‘I could tell it was an English production, because they were always serving tea,’ he jokes.

While Rossano Brazzi drove for the ‘in-car’ close-ups – that’s him, as Beckerman, putting on the classic Renauld Speculator sunglasses in the movie – it was Moruzzi who piloted it for all the general driving shots, and if you freeze-frame a DVD you can clearly make out his profile in some of the footage taken side-on. Sadly, after all these years, he has no idea which car he took up to Aosta. In the movie, it’s wearing an Italian motor trade plate not allocated to a particular car.

Moruzzi told Drive-My that, contrary to accepted wisdom, he believes the ‘action vehicle’ was chosen to match the colour of the wrecked car, rather than the latter being repainted to suit the brand-new example. If that’s the case, you have to wonder whether – assuming 3586 was the movie car – it had its specification changed from Rosso to Arancio for that reason, rather than at a customer’s request. It would make sense, given the tight timescale between the car being built and it being delivered for filming.

It’s been suggested that Lamborghini kept a register at the factory gate, in which details of cars entering and leaving on road test were recorded so that fuel duty could be recovered from the tax authorities. Moruzzi is dismissive of this idea. ‘We just filled a car up, got a receipt from the fuel station and claimed it back from accounts,’ he says. At the moment Enrico Maffeo, head of Lamborghini’s heritage department, cannot confirm whether such a register survives.

Moruzzi has one crucial recollection. The ‘elephant in the room’ regarding 3586’s supposed identity as the movie car has always been why, if its interior trim specification was altered to white leather pre-delivery, does it clearly have a black driver’s seat in the movie?

The answer, logically, would be that Lamborghini swapped the seats temporarily so that the immaculate white leather didn’t get marked during filming. Moruzzi thinks that the black seat was indeed a temporary substitution. Don’t forget, it’s highly unlikely that the car’s first owner would have had any idea that his car had just been driven 1000 miles to make a movie – and that is why the speedometer was disconnected, as can be seen during some of the in-car shots. Our previously mentioned anonymous

Lamborghini insider adds that, in this period, extensive detours through Europe were not uncommon when new cars were being delivered to dealerships, and it was routine to uncouple the speedometers.

So far, all these clues are intriguing but hardly conclusive. The most convincing evidence for 3586 being The Italian Job Miura is, ironically, something that at first sight may seem trivial: the stitching, graining and perforations in the interior trim.

It was French classic car broker Eric Broutin who made the breakthrough connection. He explains how he first came to think that 3586 might have been the car from the movie.

‘In early 2013, one of our customers tasked us with finding a good Lamborghini Miura P400. We had known for some time about 3586, which was in the collection of Sig Norberto Ferretti, the founder and owner of the Ferretti Group, one of Italy’s most famous yacht builders.

Sig Ferretti had decided to sell most of his collection, so we went down to Italy and did a deal.’

(A quick aside here: the Lamborghini distributor Zani, to whom 3586 was delivered in 1968, was owned by the Ferretti family. The car had come full circle and had been bought back by Norberto in 2005 after passing through a handful of other owners.)

‘In April 2013, we delivered the car to its new owner in Paris. Funnily enough, his first reaction was: “Stunning car – it has the same colour combination as the one in The Italian Job movie.”

‘Back home, we started to think about that. We watched the opening scenes of the movie again and again, image by image, zooming in on every possible detail. This is how we first realised that what had started as a kind of joke might actually have some basis in fact.

By comparing the stitching and hole patterns in the headrest and dashboard, we realised that 3586 and The Italian Job Miura had the very same headrest and dashboard, with the same faults in the same places.’

That may sound faintly ridiculous but, when you start to think about it, this observation is actually very significant. Lamborghini trim in 1968 would have been assembled by middle-aged mamas using traditional sewing machines. Every piece would have been subtly different, because they were made by hand. And the undeniable fact is, if you blow-up particular frames from the movie, you can see that irregularities in the line of stitching on the dashtop, and the perforations in the headrest – even particular marks of the grain in the black vinyl dash covering – match the trim in the car perfectly. It’s like comparing fingerprints.

TECH DATA

1968 Lamborghini Miura P400

ENGINE 3929cc all-alloy V12, transversely mounted, DOHC per bank, four triple-choke Weber carburettors

POWER 350bhp @ 7000rpm

TORQUE 262lbft @ 5000rpm

TRANSMISSION Five-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

STEERING Rack and pinion

SUSPENSION Front and rear: double wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bars

BRAKES Girling discs

WEIGHT 1125kg

PERFORMANCE Top speed 170mph / 0-60mph 6.7sec

We’ve replicated Eric Broutin’s comparative photos towards the end of this feature, on page 68. There are multiple points of similarity, and it’s hard to believe that they could have been faked. While anything is possible, you’d have to suppose a major conspiracy and an enormously difficult work of imitation. Retrimming a car neatly is hard enough. Imagine how difficult it would be to stitch a dashtop cover – and then stretch it over the underlying casing – so that it had exactly the same irregularities as another car’s, and the same grain pattern. That defies belief.

Drive-My finally became converts while we were watching the movie’s opening scenes on a large Apple monitor. Senior designer Robert Hefferon noted what appeared to be a faint smudge on the Miura’s headlining, something that hadn’t been picked up by Eric Broutin in his otherwise exhaustive analysis. It was hard to decipher it on the movie, but we resolved to check it out when we saw 3586 in the metal.

‘WHAT WAS THE IDENTITY OF THE WRECKED MIURA THAT WAS BULLDOZED OVER THE SIDE OF A MOUNTAIN? AND WHAT HAPPENED TO IT AFTERWARDS?’

The cause of the ‘smudge’ was instantly obvious when we opened the car door. It’s a darkening caused by a cluster of tiny perforations in the headlining, where the end of a seam disrupts their normally even spacing across the material. And it’s only apparent on the driver’s side, not the passenger’s. In other words, it’s a unique freak of manufacture, and yet another link between the movie car and Miura 3586.

We should point out that not everyone is convinced by this kind of analysis. Some eminent Italian historians are sceptical, and Enrico Maffeo says that Lamborghini is, as yet not prepared to authenticate 3586 as the movie car. Perhaps the most committed opposition comes from classic car broker Simon Kidston, who is not only a Miura expert but also a fan of The Italian Job – and who at one time was offering 3586 for sale.

Among the believers, however, are US Miura enthusiast and author Joe Sackey, and the presidents of the Lamborghini clubs of Germany and Belgium. Drive-My can’t state categorically that 3586 is ‘the Miura from The Italian Job but during the course of our own researches, we’ve become a lot more amenable to the suggestion. Your own opinions would be welcomed.

Because the car isn’t currently registered in the UK, we couldn’t drive it on public roads. But even just a few minutes roaring up and down a private track at Iain Tyrrell’s premises was enough to show that this low- mileage Miura is practically straining at the leash for a proper high-speed journey to limber it up and blow out the cobwebs. It pulls strongly from low revs and that immortal V12 makes the most spine-tingling noise as it gets into his stride. Early Miuras weren’t the most sorted cars, dynamically, but we suspect that this example would prove one of the best of its kind.

Sadly, we can only dream about driving it to the Great St Bernard Pass and recreating those iconic moments from a classic movie. Which raises another as-yet unsolved question. What was the identity of the wrecked Miura that was bulldozed over the side of a mountain? And whatever happened to it? Are there, perhaps, in a wooden shack somewhere near Aosta, the remains of another bright orange Lamborghini?

THANKS TO Eric Broutin, Massimo Delbo, Simon Kidston, Enrico Maffeo, Enzo Moruzzi, Olivier Nameche, Stefano Pasini, David Salamone, lain TyireU, Peter Wolf, Da/id Wynn-Jones.

STITCHING TOGETHER THE EVIDENCE

The most convincing reasons for crediting chassis 3586 as the Miura used in The Italian Job are to be found in its cockpit. Look closely!

THE DRIVER’S HEADREST

Although it’s now inclined rather more forwards than it was 46 years ago, the white leather headrest visible behind Rossano Brazzi in the driving shots(above) bears striking similarities to the one in 3586. In particular, the arrangement of the perforations where each horizontal facing strip is sewn to the rest of the cover match exactly in the ‘then’ and ‘now’ images, even though every one is slightly different. Note, too, the single enlarged perforation located at ‘F’; the way the perforations rise and fall in a distinctive wave pattern at ‘G’; and the horizontal misalignment of the securing screw at ‘H’ compared with its counterpart nearest the camera.

DASHBOARD AND INSTRUMENT COWL

Compare 3586’s dashboard (inset, above) with the one in the movie car’s, and you’ll see that in both images the stitching across the front follows the same irregular line. Furthermore, there’s a noticeable V-shape (circled) to the bottom of the material wrapped around the revcounter. Below are dashboard images from 3586 (top) and an enlarged frame from the movie (centre), with the individual stitches picked out (bottom) for comparison. The way they rise and fall at random points is identical, bearing in mind slight variations in camera angle. On the original images, you can see that the grain of the vinyl matches exactly, too – just like comparing the whorls of a fingerprint.

Clockwise from right. David Wynn-Jones, who in 1968 was an 18-year-old camera assistant with the crew filming the movie’s opening scenes, took these rare pictures of the Miura with lights and cameras attached. ‘We had three cameras mounted on the car, and one inside looking over the actor’s shoulder. I sat in the boot with three switches because I was the smallest!’ Because the car was on loan, it couldn’t be damaged and so the cameras were simply lashed onto it with rope and lengths of wood, to obtain action shots like the one below.