It’s too good to be a normal car. It is unlike other ever made. It does things cars can’t do Gavin Green drives the Porsche 959. One hundred and sixty miles an hour. Time to change into top. Move the stumpy gearlever, fitted with leather knob and gaiter, straight back into sixth. The engine pauses momentarily, then bursts back into life once the lever is safely secured into the bottom right corner of the double H-gate.

And so the acceleration inexorably continues. The German autobahn, once a wide motorway of hard shoulder, two distinct lanes, and a grass verge around the central reservation, resembles a narrow country lane. Once straight, it now seems winding, tight.

The pine trees which border the road become an amorphous green blur. Corners that seemed a mile oil are suddenly upon you. Alas, tar ahead, are also a pair of lorries, labouring in the slow lane. You must back off, be circumspect. You were on the way to 300km/h – 188mph – the fastest you’ve ever been in a car. If you had kept the throttle pedal hard down, you would soon have been there, for even at speeds above 150mph, this Porsche pulls in the horizon with unceasing vigour. But the thought of a lorry suddenly pulling out while travelling 140mph slower than you, is too frightening. So, at just over a true 175mph. the right foot comes off the throttle and touches the brake. The whole car jolts slightly, as the big disc pads grip, and the engine changes note – from an accelerative wail to a decelerate bellow. The Porsche still races past the lorries, doing a good 130mph.

It is not difficult to drive a Porsche 959 at these speeds. Far from it, it’s as stable as an Audi or BMW at 70, and quiet, too. At more than 150, the engine – which growls and wails truculently under hard acceleration – is a distant drone. Wind noise is negligible. The tyres hum, but not obtrusively. There’s no need to make corrections to the steering to keep the rocket on path: no need to fight against side winds or minute bumps which may send lesser cars off course. In most supercars, you have to work hard at speeds over 150. In a 959, the most advanced and fastest production road car ever made, your role is merely that of controlling passenger. The car does all the work, copes with most of the dangers, and transcends the normal limitations placed on machines with four wheels, an engine and a metal body. The effort needed to work the car up to 160mph or so, and slay there, is minimal. What you do need plenty of though, is concentration. Daydreaming, and 150mph on crowded autobahns, are the stuff of nightmares.

Not only is the Porsche 959 fuss-free at high speed, it is an easy car to drive at low speed, and around town. The complicated mechanical specification – electronically controlled four-wheel-drive, six-speed gearbox, adjustable ride height and dampers, two sequential turbos – does not call for an unusual driving technique. Rather, the 959 is one of the easiest supercars to drive. The clutch, although firm, is far lighter than a Ferrari GTO’s or Testarossa’s. It is a gentle device, too, that has none of the hair-trigger snap of the normal 911’s. The gearchange, gently spring-loaded towards the third-fourth plane, is short of throw, and precise. Its action is light, and as foolproof as that of any Ford change.

The steering has the same ratio as the 911‘s, and is servo-assisted. It is firm and sharp, yet can still easily be wielded by someone of slim build. But as with the Quattro, and other power-assisted all-wheel-drive systems, there is a curious deadness about it. The steering is sharp and responsive, all right, but it doesn’t sing in the palms of your hands in the way the steering of rear-drive sports cars, such as the Ferrari 288 GTO and Porsche 911 930, does. It doesn’t load up during fast cornering, follow the camber of the road, or kick back over sharp bumps. The steering, as with so many other functions of this car, has been tamed. Similarly, the brakes do not need a particularly hefty jerk to be activated. There is almost no travel before the pads bite the four vast centrally ventilated and laterally drilled discs. Massive retardation follows. And further to help the 959’s ability to putter in town, the view from the driver’s seat is excellent.

Take up station behind the wheel for the first time, and a Porsche 959 docs not feel intimidating. You don’t sit particularly low; the car docs not feel vast or heavy. It’s partly its compactness that produces such insouciance. The cockpit is narrow; passengers travel almost too sociably close. The nose is rot long: the front wings finish only a couple of arm lengths in front of you. And the back of the car, crowned by an integrated rear wing, is clearly in view, not far behind. While the cockpit may not be particularly friendly – its tones are too sombre for that – it has a look of normality, which some people will find inviting. There are no high tech switches, or electronic displays. The interior is the least high-tech part of the car, in contrast with that of some pseudo-performance machines.

Behind the standard 911 wheel, trimmed in leather, is a normal looking 911/930-series instrument binnacle, complete with normal white-on-black analogue gauges. Only the calibrations – the speedo doesn’t run out of numbers until 340km/h – are unusual. Right in front of the driver’s line of sight is the tachometer – the largest gauge on the dash – which is red-lined at 7300rpm. There are gauges for water temperature (for the heads, the rest of the engine is air-cooled), oil temperature, oil pressure, fuel level and turbo boost (from 0 to 2.5 bar). The only unusual instruments on the facia are two which tell the driver about the amount of lock of the two control clutches. One of these is at the heart of the four-wheel-drive system. The computerised control unit for the all-wheel-drive draws on engine output (determined by boost pressure) and wheel speed (delivered by wheel sensors). It computes its findings, and sends messages to an electro-hydraulic actuator, which in turn varies the laminae pressures in the PSK control clutch, located between the gearbox and front differential. Thus, the amount of drive sent to the front axle is varied. In bald terms, when the front wheels need lots of grip, they get it. At constant speed, the front axle gets 40percent of the drive; during full-blooded acceleration tests, the front gets only 20 percent of the drive force, the second PSK control clutch is mounted in the rear differential, for limited slip traction-control purposes.

All this may sound extremely complicated, but it needn’t bother the driver. There is never any discernible hint of the drive changing, from front to rear axle or vice versa. All the driver need worry about is a column mounted wand, which tells the computer controlled drive system what sort of conditions it is trying to master. There are four stalk positions: dry road, rain, snow, off-road. The driver just puts the stalk into the right place, and the computer then sorts out the rest.

There are two other unusual controls. One alters the damping, the other the ride height. Both switches are on the centre console. There are three positions for each control. The damping switch alters the firmness of the shock absorbers. In addition, the dampers automatically stiffen when speeds increase. The ride height switch, which activates a hydropneumatic levelling control, offers three choices of ground clearance: 120mm, 150mm and 180mm. Self-levelling ensures that the car stays at the ride height selected, independent of load. At speed, however, the car will automatically lower itself, regardless of the height chosen. At more than 150km/h (94mph), the 959 rides at 120mm (4.7in).

’You can converse at 175mph. The car remains stable arid relatively quiet’

Apart from the four-wheel-drive control column stalk, and the two rotary switches on the centre console, the remaining switchgear is prosaic. In typical 911 fashion, it is quite haphazardly arranged, and not of the finest quality. Lots of old fashioned push-pull switches litter the dash. And the facia itself is skinned in unattractive black leatherette cloth. Real leather clothes the door casings.

The seats are standard 911/930-series – in this car upholstered in grey wool. Electric controls look after the driver seat movement. Lateral support is poor: go around a corner quickly – as you’re soon to do – and the tyres arrest any car body movement better than the seal controls your body. Two tiny occasional rear seats, smaller than those fitted to the 911, snuggle in behind the front chairs. Their squabs fold forward, providing the most effective stowage space in the car. The boot, in the nose, is too shallow to hold anything bulkier than jackets or briefcases. It is noticeably smaller than the 911 trunk, owing to the intrusion of the larger fuel tank (18.8gal) and front differential.

Settle yourself behind the wheel. Feel the clutch (firm) and the gears (which are easily shifted). You sit quite square in the car, behind a normal 911 screen, and two faintly ridiculous (on a car so technologically advanced) conventional wipers. A Porsche engineer – we are at Weissach, the company’s engineering nerve centre – takes you through the controls. ‘The car is very straightforward. Have you driven a 911? Then you will have no problem. It is a very easy car to drive. You’re shown the unusual display which warns of tyre pressure loss. ‘The tyres are so wide, and of such low profile, that a driver may not be aware of a slow puncture.’ The rubber – made by Bridgestone – is of run-flat design. The fronts are 235/45VR17S, the rears 255/40VR17s. There is no spare, not even a rudimentary space saver.

The door, of 911 design but made of aluminium rather than steel, is shut behind you (it doesn’t open as wide as do the doors on the 911, that much becomes obvious when you climb over the wide sill extensions into the car). The Porsche engineer, suitably clad in expensive watch and designer T-shirt, waves goodbye. The winding secondaries around Weissach, and beyond, beckon. No British journalist has driven Porsche’s fastest, most expensive car, on a public road before. This one-day exercise is part of a limited press launch, involving only those magazines which Porsche reckons matter us, the US duo of Car and Driver and Automobile. Auto Motor Und Sport in Germany, L’Equipe in France and Paul Frere for Road & Track. The security gates at Weissach open, the guard gives a little wave, and 420.000 marks (£145.000) worth of Kevlar bodied (apart from aluminium doors and bootlid) wundemagen is let loose for the day.

The engine, stuck out the back in typical Porsche style, wails in the normal flat-six Porsche 911 tone – although the twin turbos do soften its glorious rear.

Hydraulic tappets quieten it further. First, actually known as the G-gear (for gelande, or super low) is good only for 35mph: you can start the car easily in second, which stretches to just over 60mph. So far, everything is simple: you could almost be driving a Fiesta. The power, at low to medium revs, is not enormous, either. Porsche’s sequential turbo system allows for one of the identically sized blowers to operate from low revs, when all the exhaust gas is directed to it allowing it to build revs rapidly At higher revs, the additional blower is engaged.

Below 4500rpm, a 959 feels fast, but not that much quicker than a normal 911. You can even be excused, as you drive smoothly and briskly over the twisting poorly surfaced roads around Weissach, for wondering what all the fuss has been about. Why have customers been waiting four years for one of these monsters, when a normal 911 – which costs almost only one-fifth as much, and has a better panel fit and paint finish, and sounds better to boot – could be had tomorrow? Spin the engine around to 4500rpm, and you’ll find out.

Suddenly, an eruption behind your right shoulder interrupts the muted engine note, and the 959 charges violently forward. That second turbo comes in like an afterburner, and your back, nestling comfortably in the seat, is suddenly gripped by the back rest. Your head is forced rearward, too. The whole beast springs into life like some frenzied animal surging forward with irresistible urgency Seven-three on the tacho, change into fourth, the needle fails back to just under 5000 and, after a momentary hesitation for the gearchange, returns to the 7300 mark, again with impossible-seeming alacrity. Change into fifth, you’ve passed 200km/h (125mph), and are going far too fast for a secondary road, so you back off. Your palms are sweating Calm yourself, before confronting the blast along the autobahn.

That’s when the serious speed comes. That’s when the silver Porsche, with a sharper flatter nose than the 911s on which it’s based, and the wider squarer tail, will surge past superheated BMWs and Benzs and Golf GTis and big Opels with crushing superiority. When the big powerful saloons are left behind – they disappear surprisingly quickly from the rear view mirror and when the road ahead is clear, it’s time properly to exercise the fastest road car in the world. The 200km/h at which you’ve been cruising becomes 210,220, and the car is still surging forward, unerringly steady, pleasingly quiet, seemingly expending no real effort. At just over 250km/h – 160mph – the redline says go no further, so you grab sixth and still the car thrusts onward. And it’s still easy going, still quiet, still accelerating strongly. This car seems to defy the law of physics which impedes Ferrari Testarossas and GTOs and Lamborghini Countachs and Aston Vantages back at 160 and beyond. Every other fast car in the world struggles when grasping at higher velocities, gaining those extra mph slowly. And they’ve done so for the last 20 years. Not this one. This is a performance car on a different plane from every other. At 280km/h – 175mph – the car is still surging ahead relentlessly, still handling its speed with unfussed confidence. You can still converse at that speed. The car remains stable, relatively quiet. But the traffic ahead prevents you from reaching that magic 300km/h mark. Sadly, poor weather and continuing heavy traffic mean you never achieve it. Other magazines have, though. Auto Motor und Sport clocked the 959 at 317km/h – 197mph. That’s exactly the speed that Porsche itself claims. Ferrari GTOs and Countachs are just not in that league. In standing start acceleration tests, the 959 scores an even more emphatic victory over its rivals (if it has any). Helped enormously by its four-wheel-drive, the Porsche can sprint from 0-62mph in 3.7sec, 0-100mph in 8.3sec, and 0-125mph in 12.8sec. It covers the standing quarter mile in 11.9sec. No other supercar even gets close to those times. Once again, a Ferrari GTO is made to look ordinary.

Off the autobahn, onto roads that wind through the Black Forest – roads that are beautifully cambered, wide enough to accommodate real speed, and relatively free from traffic. What traffic is encountered is dispensed with quickly, cleanly. Apart from what the speedometer is telling you, the other traffic is the only tangible sign of this 959’s velocity. You approach slower cars like a missile closing in on a battleship, steering around the other vehicle at the last minute, and powering on down the road. The slower car almost instantly disappears from the mirror. The next car ahead is met, and dismissed. And all this, as always, is accompanied by minimal wind or road noise, and with a muted wail from the 2.85-litre flat-six. Even at big revolutions, when the second blower has settled into its rhythm, and is supercharging the performance of the 959, the engine note is nowhere near as noisy as an Italian supercar unit. You just don’t get the delicious, inspirational noises that emerge from a Testarossa or Countach or 328GTB or even the 911. There’s a growl there, all right, but ii seems distant, and restrained. The engine’s relative quietness reinforces the high speed missile – rather than high speed road car – feel of this machine. It’s almost too good to be a normal car. It is so unlike any other ever made, in its power and in its roadholding capabilities, that it stops feeling like a car. This machine is beyond such limitations. Alien. It does things cars can’t do.

Around large radius, fast bends, its guided missile character is particularly evident. The 959 stays flat, its tyres avoid so much as a chirp, it handles neutrally, the steering feels strangely desensitised yet sharp, and the car just goes where it is pointed What it lacks is feedback. Sure, the steering is so responsive that a minor jerk would charge the attitude of the car, and a dab on the brake would wipe off speed almost as effectively as running into a brick wall. Accelerate, and the car will charge. Yet in normal steady state fast driving, the car simply goes. It doesn’t send messages through the steering wheel that the camber is wrong, or that the road is bumpy. Rough patches of road are ridden with extraordinary aplomb by the electronically adjustable dampers, and by the all-round wishbone self-levelling suspension. You feel eerily isolated from the road surface, unlike in most sports cars where the slightest bump can make you wince. And then there’s the quietness, of which we’ve already spoken. It all amounts to a strange feeling of isolation from the car. To a feeling that this beast is so supreme a machine that the Porsche engineers have forgotten one vital ingredient: human involvement. Sure, you have to guide the machine, and you get the thrill of going safely at extraordinarily high speeds. But you don’t enjoy the feeling of a man and machine fighting together, to conquer a difficult road. Rather the machine does most of the work. You have to concentrate only to avoid running up the back of other cars.

Obviously, some skill is needed to point the beast accurately when you’re powering through sweeping roads at more than 100mph. going at least twice as fast as anyone else on the road. You need to have some idea about cornering lines, for instance. But you can let the tyres and traction take care of the grip, and the enormous torque and power of the engine – which give punch in almost any gear – take care of the go.

When you really take the 959 by the scruff of the neck, and ask it to give its all on tighter corners, you start getting a bit more attitude, and feedback. Pushed hard into a tight bend, the car will understeer quite discernibly. Back off, and the nose tightens its line, as weight is transferred to the nose. Forget about any nasty mid-corner snap, which can see a 911 charge off the road. Nonetheless you can still feel the car moving in relation to its tyres and you can feel it needing some correction. It’s a pleasant experience.

On tighter corners, the car is quite throttle responsive. You can steer the machine on the right pedal, when really tanking on. Back off, the nose tucks in. Power again, and the car enters a totally controllable four-wheel drift, if the speed is high enough, with just a touch of oversteer. On the tighter turns, you can throw the 959 around. It is by nature composed and stable and neat, though. Sideways driving is not really part of its wonted behaviour. It lacks me handling exuberance of a GTO, ever if it replaces it with handling excellence.

The 959 also tacks the design flair of the GTO; of that there can be little doubt. It is designed to be stable at high speed, and to cleave the air with maximum efficiency (its Cd is 0.31). It is not meant to look pretty. It doesn’t. Instead, it looks what it is – efficient, and rather soulless. The panel fit on our test car was poor, the paint finish not the best. Production cars of which there will be 200 (seven, have been built as we go to press), will be better. Porsche says. Porsche is hoping to deliver all the cars by March next year (1987 Drive-my remark).

‘Porsche sees the 959 as its showcase. Look guys, this is what we can do’

Between the axles the car looks almost identical to the 911, apart from the side skirts and the broader wheel-arches. The roof line looks the same, the glass area looks the same, the door catch is the same. To the 930/911-style centre section are added the bits which distinguish this car from its lesser brethren: the chisel nose, all the better to cleave the air, the wide rear to house the engine and ancillaries. There are slats and ducts and holes all over. The starfish pattern magnesium alloy wheels look vast, are vast.

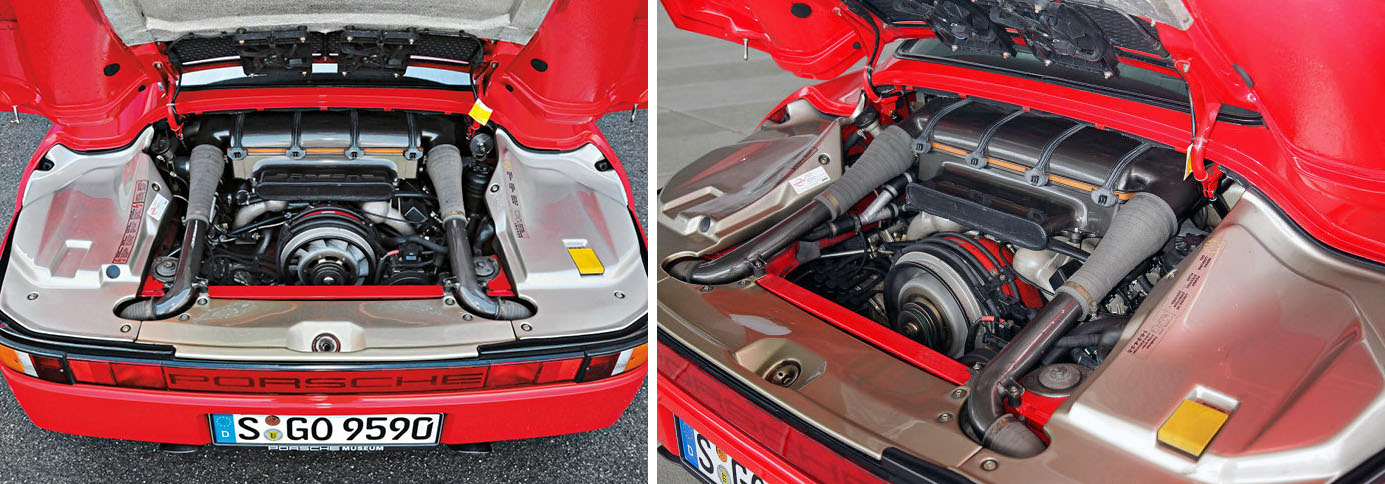

Open the engine cover, and the visual disappointment continues. The spec sheet talks about 450bhp and twin turbos and titanium conrods and forged light alloy pistons and Nikasti coated cylinder barrels and four-valve water-cooled cylinder heads and quad cams and sodium filled exhaust valves and twin intercoolers. But when you open the bonnet all you’ll see are pulleys and belts and part of the induction system. The engine doesn’t even look big. and it certainly doesn’t look powerful. How can such a little ordinary looking engine produce such a wallop?

Efficiency, not ostentation. Speed, not thrills. Enormous competence, not character. Excellence, not extravagance. That’s what the 959 is about. It is the finest fast car ever made, of that there is little doubt No car, ever built, can boast of its combination of speed and stability, of quietness and ride comfort. And no car has yet embraced this level of technology. Porsche, which is in the business of selling technology, as well as selling cars, no doubt sees the 959 as its showcase. Look guys, this is what we can do. That’s the message the Stuttgart firm is trying to promulgate.

Of course, the 959 is utterly magnificent. The greatest sports car of all. A car that quashes, easily, the Countach and the GTO and the Testarossa. A car unlikely to be rivalled for years to come. Yet, on my way back from Stuttgart after a day experiencing a new sort of motoring sensation – and of setting a personal best for maximum speed – I feel strangely unmoved. I don’t really want one. Somehow, the car is too efficient, too tame, almost too good. It doesn’t sing and dance and live and breathe in the way that the best Italians – and in the way that the humble 911 – do. In its determination to make the world’s greatest road machine. Porsche has forgotten to involve the bloke behind the wheel.

High-tech meets low-tech. Amazingly, car uses load-free fuel. Interior narrow, seats could be belter. Boot perfunctory. Console controls dampers and ride height.

Instrument panel similar to standard 930/911s, as is steering wheel. Some functions unique: stalk behind wiper control tells computer of ambient conditions; monitor for tyre pressures.

Superb wind-cheating detailing Includes articulated headlamp washers, unusually shaped mirrors. Engine looks ordinary but is stunning: 450bhp flat-six, twin turbos and titanium conrods.

Bridgestone run-flat tyres supplied as original equipment. Conditions often wet, ameliorated by computer adjustable drive system. Even under hard cornering car stays flat, predictable.

Thanks to Porsche 959 Club