Flashing down the RN31 at Reims. So says Mick Walsh after a thrilling drive in the ERA E-type, a car that is beginning to fulfil its potential thanks to the dedication of one man. Photography Tony Baker. Designer Berthon clearly paid close attention to the German GP machines. The sight of the awesome Silver Arrows lapping ERAs around Donington in 1937 must have pained English race fans. When the Association Internationale des Automobile Clubs Reconnus announced a 3-litre Grand Prix formula for 1938, the Bourne-based team backed by Humphrey Cook optimistically started planning a new car called the E-type to take on Europe’s finest.

Sadly, the ambitious project followed the pattern of all Raymond Mays’ future schemes. A shortage of funds forced the team to switch to a replacement voiturette but its advanced design was carried through.

The new racer certainly looked the business, and designer Peter Berthon had clearly paid close attention to the masterful German Grand Prix machines, particularly the Mercedes W154. To save costs, the engine was eventually derived from the old 1487cc ERA ‘six’ with a Zoller supercharger boosting power to 260bhp. The independently sprung tubular ladder chassis was more advanced, with a geared-down propshaft that ran 6in below the height of the hubs to a new four-speed, all-synchromesh transaxle.

In stark contrast to the 17 earlier ERAs, the dramatic new E-type featured a sleek aerodynamic body wrapping the tightly fitted mechanicals and low seating position. The front suspension followed the Porsche-style torsion bar layout used in the C/D-types but with shortened arms and different lengths to accommodate the convoluted steering route. The unpainted original design initially looked like a W125 clone and featured a 2.2-litre engine and swing- axles at the rear, but in secret tests at Donington in July ’38 it suffered from alarming handling. The car was subsequently redesigned around a de Dion axle and trailing arms.

The public debut at Brooklands on 2 May, 1939 was typical of the extravagant, unresolved project. Despite being withdrawn after a few uncompetitive practice laps, the static car created intense interest, but behind the scenes the team was already unsettled.

The Brooklands fiasco was the last straw for Humphrey Cook and, after falling out with Raymond Mays, he withdrew his support and the team relocated to Donington to focus on getting the E-type race-ready. Berthon had pledged two cars for the Coupe de la Commission event at Reims, where Arthur Dobson initially stunned everyone by setting a 101mph lap – during which the Mercedes team clocked the little racer at 172mph down the long straight. But the optimism was again short-lived as overheating caused engine problems, and the solitary E-type entry was scrubbed.

A test at Montlhery looked more hopeful after extra louvres had been cut in the bonnet, and the ERA finally made its racing debut at Albi. Dobson led from the front row but the engine began to misfire after he had set the fastest lap. He eventually spun off, crushing the long tail and damaging the rear suspension.

A second E-type, designated GP2, was nearly completed in time for a two-car assault on the

Nuffield Trophy but the outbreak of war resulted in the Donington event’s cancellation and the racers went into storage. ERA Ltd sold both cars in 1946, GP1 to Peter Whitehead and GP2 to Leslie Brooke. Frustration continued for both drivers, Brooke even shipping GP2 to Indianapolis, where gearbox problems meant that the car failed to qualify for the 500.

GPl’s next owner, Reg Parnell, didn’t fare much better, but Whitehead bought back the broken racer for another attempt to sort its potential. With co-owner Peter Walker in the driving seat for 1949, GP1 finally started to reach the chequered flag, with several strong finishes at Goodwood, plus fifth in the Daily Express International Trophy at Silverstone.

Above: superb Max Millar cutaway art clearly shows drop-down driveline and de Dion rear end. Below: the compact gearbox gate is a joy to operate

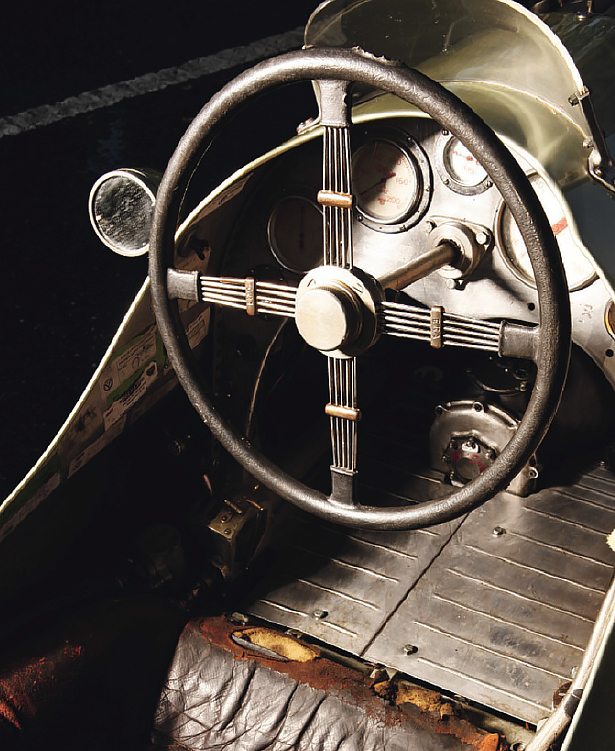

Clockwise: evocative cockpit with battered seat, white dials and broad wheel; Dobson leads away from pole position at Albi in 1939; Porsche-style front suspension; 19in wheels really set off lines

In 1950, Walker’s last race ended in dramatic style. While practising for the British Empire Trophy on the Isle of Man, a halfshaft failed and ruptured the fuel tank. Walker broke several ribs when jumping out, and the resulting blaze set alight a hedge and building close to the accident. The drama continued when the fire engine ran out of extinguishant, but photos show jovial locals standing around the smouldering wreck. Walker claimed on his insurance and the engine was sold to Rob Walker, who subsequently fitted it into a spare GP Delage chassis. The rest was eventually acquired by Jim Berry, who used the chassis and suspension as the basis for a Jaguar XK-powered sports car. Registered TKD 100, the special was successful in north-western events, including a race win at Aintree in 1955.

The true saviour of the E-type was Gordon Chapman. He bought the remains of GP1 in 1959, and set about tracking down surviving components, including a spare engine from the Wharton family. Chapman also purchased GP2 in 1966, and slowly the two cars were rebuilt. Restorer and experienced ERA exponent Duncan Ricketts was commissioned to remake the body for Chapman, and finally the project started to take shape. While racing RIB for Sally Marsh, Ricketts acquired the unfinished GP1 from the Chapman family, and began a deter-mined effort to return it to racing.

The restoration proved to be a major challenge because the more Ricketts investigated the design, the clearer the fundamental flaws became. “Maybe they were trying too hard to push the boundaries, but I’m amazed by how much ERA achieved in the circumstances,” he says.

Revelations included the problematic de Dion rear suspension: “I have no idea why they made it solid, which meant that it acted as a torsion bar. Not surprisingly, after a few races it broke in two. The bearing that ERA fitted in the middle allowed it to rotate, but the subsequent flex while cornering caused wheel wobble. I solved this by making longer plain bearings in the middle of the three-part de Dion. At the first Mallory test the car kept spinning, so I made it stiffer with two tubes inside each other and reinforced the gussets. The car now handles well, and at high speed it’s very stable.

Changing gear with your left hand takes focus, but the action is slick and precise.

From above: dramatic profile and low seating position have more than a hint of Mercedes; patriotic badge; GP1 in unpainted form at Bourne in 1939.

“The chassis is extremely rigid and really didn’t need the extra strengthening that ERA made, which only added extra weight. The plan with the bigger tyres was to make fewer fuel stops, while Mercedes was the inspiration for the independent suspension. Compared to a В-type, it’s a big step forward.”

The complex steering design features a rack and pinion with four joints: “The keyways that taper on the main shaft were only ‘/sin and if you turned the wheel too hard or hit a kerb, they broke. It happened to ‘Wilkie’ Wilkinson in the 1947 French GP, and the same thing caught me out when testing at Mallory. All of a sudden the car just spun and was impossible to push because the steering had failed. Bigger keyways solved the problem, and now it’s wonderful.”

Repainted in a light metallic green and riding on authentic 19in wheels, the sleek racer is a much-admired entry wherever it competes. “I could have put it on 16s and run away from everybody but it would have looked terrible,” says Ricketts. After inevitable teething troubles as GP1 was sorted, Ricketts is consistently a front-runner against ERA regulars. And then finally, in 2000, came the car’s first-ever win when he headed a very wet race for pre-1952 single-seaters at VSCC Silverstone.

Ricketts persevered with GP1, both on track and in hillclimbs. The engine’s flexibility comes into its own in poor conditions: “Donington is my favourite circuit – in the wet, you can keep it in top because the torque is incredible. From 4000rpm it pulls like a train. It doesn’t like slow right-hand corners, though, because the carburettors are on the wrong side and it goes flat. Getting into first is also tricky – the engine almost dies going around the hairpin at Mallory.

“On a long straight it’s very fast. Even at 150mph it’s still starting to pick up, which is quite scary. The handling is similar to the Dixon Riley, which I’ve also been lucky to race. With 50:50 weight balance, it’s very neutral but you can’t get the tail out. If you do, you’ve lost it. Racing GP1 is a real struggle because you never know what’s going to go wrong next!”

Having appreciated Ricketts’ dedication to GP1 through the years, and admired his effortless car control, it was a privilege to try this rare beauty. Whereas you step up to the earlier ERAs, the E-type is easy to enter thanks to its advanced driveline. The flat, low driving position seems a generation younger. Your sides feel very exposed once you are ensconced in the wonderfully battered leather seat, and your legs lie flat around the step-down gear casing.

The clutch and brake pedals are floor- mounted but the drilled centre throttle is hinged from the bulkhead. The rear radius arms and fuel line run along the exposed siamesed main chassis rails, while sitting snugly to the left by the seat is a stubby gearlever on a neat quadrant marked with Roman numerals. Changing with your left hand requires focus but the action – with first inside and forward – is slick and precise.

“Racing starts are a quandary,” says Ricketts. “The spinning wheels act like a clutch but I always worry about breaking the driveshafts. Slip the clutch too much and it burns out. Thankfully the big wheels aren’t too grippy but the gearing is high so first feels like second.”

The purposeful cockpit has a cut-out top to provide extra light for the Smiths instruments, and the streamlined aeroscreen looks as if it was borrowed from a Hawker fighter plane. The top of the broad four-spoke Bluemel’s-style sprung wheel matches the peak of the ’screen, so with arms well bent, your hands are positioned above the bonnet line. Tall drivers such as Walker looked perilously exposed.

The bare-aluminium dash has five white dials with distinctive red numbers and the famous ERA triple-ring logos. A small air-pressure gauge for the petrol tank is centred between a larger rev counter marked to 9000rpm and a bold oil-pressure dial. Supercharger boost pressure and oil temperature are set lowest, with fuel pump and magneto switches on either side.

The view down the lean bonnet to the torsion- bar suspension and the impressive finned drum brakes is hugely evocative, and you can just imagine Dobson flashing down Route Nationale 31 at Reims. The E-type has a wonderful aura despite its troublesome evolution.

It’s not just the styling and tall wheels that evoke contemporary Mercedes as the remote starter is plugged into the right-hand side of the split cowled grille. Already warm, the supercharged 2-litre erupts with a meaty, crisp bark. The throttle action is instant and, other than the screech of the blower to the right, the wonderful noise is all exhaust. Castrol R helps to lubricate the Zoller and, combined with the methanol, the smells match the car’s dramatic character.

Engine, with carbs above Zoller blower, is a snug fit under the slim body. Below, l-r: quick-release filler cap; bodywork was recreated by owner/driver Ricketts and is modelled on the original style

Depress the centre throttle and the famous twin-cam ‘six’ screams even harder. Ricketts gets around 360bhp at 6000rpm on the dyno with 281b boost. For reliability’s sake, he keeps it down to 221b, which drops power to 320bhp: “You could tune the Zoller and get 400bhp but everything else would suffer.”

As you’d expect with a power-to-weight ratio of 400bhp per ton, the E-type’s performance is spectacular. The combination of super-sharp throttle, urgent torque and progressive power fires it out of corners. Match that ferocious acceleration with beautifully weighted steering that’s a joy to work and confidence quickly builds.

The gearbox is also superb, the short, rapid action a total contrast to the preselector of the older design, but with such immense reserves of torque you really only need third and top once up to speed. “There’s no weakness in the transaxle,” explains Ricketts, “but the original synchro rings were too wide and cumbersome, so I switched from 6in to 2in.”

Unlike a beam-axle ERA, the independently sprung E-type demands more precision, which better suits the lighter controls. The Lockheed drum brakes with twin leading front shoes have excellent bite and feel, but push too hard and they’ll lock up. Through the faster turns, the E-type feels beautifully balanced, but I can’t imagine what Dobson was thinking around Reims with the constant worry of something breaking on the unsorted machine.

The responsive set-up suits Ricketts’ smooth style, and hopefully he’ll chalk up more wins in ERA’s 80th-anniversary year. If Berthon had enjoyed the historic-racing specialist’s insight, perhaps the under-financed team might have given the German and Italian outfits something to really think about. I love the idea that a former British Leyland apprentice who started building Riley specials as a hobby went on to single-handedly sort this beautiful British challenger. More impressive still, Ricketts is a rare breed of owner/ driver/mechanic, and few have a more complete appreciation of the famous marque.