Back in 1976 the Mercedes car range was much simpler than the bonanza of letters and numbers that is available now. In fact, there were only three models: a standard mid-size saloon (which was part of a long line of cars going back to the very first Mercedes models and so needed no further designation), a large luxury saloon, designated the ‘Sonderklasse’ (‘Special Class’) or merely ‘S Class’ and the ‘Sportlich-Leicht’ or ‘Sport Lightweight’ range of sleek convertibles and coupés which were anything but being prestigious and comfortable tourers based on the standard saloon car platform.

So, W123 was purely an internal designation – to those not familiar with the inner workings of Mercedes, the new model was simply the latest form of ‘the Mercedes’, a modern but conventionally engineered car which justified its steep purchase price (a basic W123 cost as much as a fully-equipped Ford Granada Ghia in the UK) not with needless toys and gizmos but with high quality materials, well-designed mechanical parts and peerless build quality.

At the time by far the biggest part of Mercedes’ income came from making commercial vehicles and the standard saloons were designed and built on very similar principles to the trucks and buses – these were vehicles built to last undertaking arduous work in tough conditions, being easy to service and simple to repair if they did go wrong. And like its predecessors the majority of the W123s were sold into a life of commercial drudgery as taxis, often with the famously immortal but infamously sluggish 2.0-litre diesel engine under the bonnet. Across northern, central and south eastern Europe, much of the Middle East and large swathes of northern and eastern Africa, the W123 was nearly standardissue at the taxi ranks. And thousands of them are still at the same work today, with interstellar mileages on their cracked and dusty odometers.

Here in the UK, the W123 was at the top of the executive car league and the sign of a motoring connoisseur – someone who could afford a flashier Rover 3500, a BMW E3 or a Jaguar but instead preferred to buy a finely-crafted, comfortable and indestructible Mercedes.

Well-heeled businessmen could opt for the C123 two-door coupé model while the county set preferred the S123 estate (much bigger than a Volvo, less gauche than a Range Rover!). But it was the taxi drivers of the world that made the W123 the most successful Mercedes car in history up to that point, with over 2.7 million being sold by the time it was replaced by the higher-tech, more European-orientated W124 in 1985.

The W123’s reputation for longevity and reliability is certainly justified but it is not absolute. A taxi pounding the streets of Lagos only has to contend with the laws of physics, while a W123 in our damp, salty climate has to withstand the laws of chemistry.

And part of the reason for the model’s apparent indestructibility is that it is very easy to service, which is different from it not needing to be serviced at all, which is how many of the second-, third- or seventh-hand buyers of these cars treated them.

Elderly W123s could be picked up for a song and run into the ground and many, especially the treasured diesel estates, were used as tradesman’s runabouts and hard-working tow vehicles.

This means that the number of W123s on the roads is nowhere near as high as it once was. Fortunately the model obtained classic status a good while ago so prices have risen to make it more worthwhile keeping them on the go. Which is what this guide is for!

BODYWORK

For all its reputation for being built like a battleship, the W123 is a conventional steel car with unitary construction so it can, and does, rust. Like most cars of its age it has a structural inner body frame and mostly unstressed outer panels. This means that cars can look very presentable while holding major rot underneath. Sills and wheel arches are the usual trouble spots but that is a matter for buying rather than owning. If new outer panels are needed they are mostly available, with the exception of some of the sections specific to estate models. Prices range from about £40 to £150 depending on the source and size of the panel.

Unlike most cars of its era the W123 was undersealed from the factory, but it only does its job if there are no cracks or peels in the layer – once moisture gets underneath all the ‘protective’ layer does is hold it against the metal more effectively. Annually touching up parts of the underseal that need it, especially in areas vulnerable to stone chips, is very worthwhile.

Blocked drain tubes in the roof gutter and for the sunroof also promotes rust and repairs around the sunroof can be seriously expensive. Opening the roof and pricking out the drain tubes at the front of the aperture is a simple job that can save major headaches later. The battery tray at the back of the engine bay was not protected well and rust easily, and starts from a spilt electrolyte and fumes given off from traditional unsealed batteries.

Early W123s didn’t have plastic inner liners in the front wheel arches and many of those that did have them will have lost them over the years. Without them the inner front wings can accumulate a large amount of mud, which can cause rot to the structural parts of the car. Where the bonnet hinges attach to the car is also a trap for muck and moisture collects here. Both these areas should be cleaned out every now and then. There are drain tubes to clear here too.

The W123 has a fully carpeted interior, which holds any water that gets inside. Leaks from door seals, windscreen rubbers or the bootlid will greatly speed up the rotting process and also damage the cabin’s soft furnishings, which are hard to replace these days. Keep an eye on the spare wheel well in the boot for pooling water, as this will point to failed seals or liners and if not put right will cause expensive-to-repair rot.

ENGINE

A very wide range of engines was offered in the W123, consisting of four- and six-cylinder petrol engines and four- and five-cylinder diesels in various capacities. Most UK cars had petrol engines—the four-cylinder 2.3-litre with a single overhead camshaft (early cars had the M115 engine, later ones the M102) and the six-cylinder 2.8-litre DOHC M110 were the most popular choices. The 2.0-litre M115/ M102 four-pots are around but left the hefty W123 very underpowered and the intermediate 2.5-litre M123 SOHC straight six was rarely chosen as it offered neither the economy of the 230 or the power of the 280.

The four-cylinder 2.0-litre diesel (the OM615) was definitely taxi fodder with only 54 horsepower in a car weighing over 1600kg. The 2.4-litre OM616 was little better but the 3.0-litre OM617 five-pot made a just-about adequate 79 horses and when a turbo was added in 1980 this jumped to a very healthy 125.

All these engines are very durable provided they receive a modicum of care – annual oil and filter changes with a good-quality lubricant are essential, and ideally the coolant should be changed at the same sort of intervals. All the engines use chain-driven overhead cams and currently have something of a reputation for snapping timing chains but this is simply because with the youngest W123 being 31 years old and probably having covered well over 250,000 miles, these parts are (finally) reaching the end of their lives. Rattles from the front end of the engine, especially when starting from cold, are the first sign and if the noises continue with a hot engine you should consider getting the chain renewed.

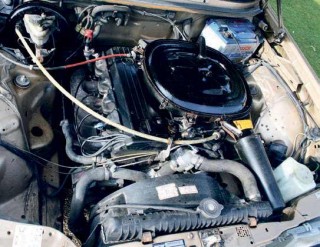

The W123 was designed with easy servicing in mind and this especially applies to the four-cylinder petrol engines which have a lot of space around them to work and all the major ancillaries are easily accessible. The 230 is a simpler engine than the twin-cam 280 and parts are cheaper and easier to find.

Lower-spec cars had Solex carburettors with automatic chokes while all six-cylinder cars and later four-pots had Bosch K-Jetronic fuel injection (that is what the ‘E’ at the end of the model designation on a W123 stands for – ‘Einspritz’ is German for ‘injection’). Both systems are generally reliable but can get troublesome in their old age as vacuum hoses and diaphragms that govern the fuel delivery perish. On carburettor-fed cars the problems usually manifest by difficulty starting when hot and ‘running on’, while injected cars suffer when starting from cold. Kits to rebuild the carbs are available, while the K-Jetronic system is best entrusted to a specialist and overhauls can be pricey. Keep an eye on external hoses and the condition of the fuel filters.

The diesels are famed for their durability and economy and they can be run on straight vegetable oil if you so choose, which has heightened their desirability. The benefit from the same regular oil and coolant changes as the petrol motors and the cleanliness of the air filter is key to provide both maximum performance and to prevent internal overheating.

The fuel filter should be changed annually and occasionally checked for trapped water to prevent damage to the fuel injectors. It is good practice to check the glow plugs at every oil change, not only to make sure the engine starts crisply in cold weather but to prevent the plugs seizing in the cylinder head, which can cause headaches if one needs to be changed.

TRANSMISSION

Four- or five-speed manuals or a three-speed automatic, all of Mercedes-Benz’ own design, were the standard transmission on the W123 family, although a more sophisticated four-speed automatic was introduced during the last years of production. All are reliable and have no particular vices – problematic units can be expensive to overhaul and so should be filtered out at the buying stage.

Most cars around today will be autos and should change gear smoothly, if not particularly quickly. A new filter and a fluid change (with standard ATF, although a synthetic seems to improve the speed of the gear shifts, especially in cold weather) every 30,000 miles or three years will help these ‘boxes go on for decades. On later four-speed automatics there is a choice of ‘Standard’ or ‘Economy’ operating modes, with the later having a more reluctant kickdown and the torque converter locks up at lower speeds. If the gearbox seems stuck in one mode then it’s usually a simply dirty electrical connection. The manual gearboxes are somewhat notchy in operation but were well-engineered and should never miss or baulk.

They have the same three-year oil change interval as the automatics and use the same ATF fluid. Unlike the automatics, not all the manual gearboxes were fitted with magnetic drain plugs at first – getting one from a later car can prevent the inevitable metal swarf from circulating in the oil.

STEERING AND SUSPENSION

The W123 was definitely ‘designed for comfort, not speed’ – the days when any Mercedes saloon was expected to have sporting credentials were a long way in the future. The suspension is soft, the seats are very well-sprung and the steering is both low-geared and light. But the sheer size of the suspension components means that they last a long time.

While needing a lot of motion to change direction, the steering shouldn’t be vague, with no more than an inch of free play at the wheel rim with the steering centred. The car shouldn’t wander around the road either, although W123s do like to ‘tramline’ on the motorway where HGVs have worn tyre grooves in the road surface.

Over a long ownership spell there’s the possibility of creeping wear building up in the steering unnoticed. As well as the steering box there are six ball joints in the linkage and small wear in all of these can build up to a lot of slack. The steering damper has a tendency to suddenly fail when one of the internal seals gives up. Neither of these parts are expensive or difficult to replace, although a worn steering box is a £2000 job to renew!

If the car feels baggy then the dampers may well be tired. Despite being softly sprung, a W123 should pass the usual ‘bounce test’ – pushing down on a corner and releasing it. It should rise, fall and return to its static position. If it keeps wobbling the dampers need replacing but this is a straightforward job.

The rear subframe is attached to the body by flexible mounts and these degrade with time. This is usually the source of any clonking noises and a sense that the car is steering from the rear. These can be replaced on the driveway providing the rear subframe can be adequately supported, although the old ones tend to be very corroded and can be hard to remove. The estate models (S123s) and higher-spec W123s had self-levelling rear suspension, powered by an engine-driven pump with hydraulic rams assisting the rear springs. It’s a simple and reliable system that runs on ZHM fluid, which should be changed every five years. Most problems are due to the levelling valve, which can seize if the car does not get loaded down regularly or leak through failed internal seals – a kit of new O-rings is available and the valve can be rebuilt on the workbench.

BRAKES

Like most of the W123’s engineering the brakes are conventional but sophisticated, consisting of discs on all four corners with servo assistance on all models. The system is easy to look after, with conventional calipers and pads.

The only quirk is the distinctly Mercedes design of the parking brake, with a foot pedal in the footwell to apply it and a large T-handle near the driver’s right knee to release it. A moment of absent-mindedness makes it easy to drive away with the brake still applied, which will rapidly wear out the handbrake pads, which are a minaturised drum-brake system where the ‘drum’ is the inner surface of the centre of the rear discs. Replacing and adjusting these can be tricky, especially if the disc is reluctant to part from the hub.

Most brake problems are related to the servo, which is supplied by an engine-driven pump which charges a reservoir to supply the rather eccentric vacuum-operated central locking system. Sudden failure of the servo can occur, but is rarely more than a sticking vacuum check valve which can be removed and sprayed with penetrating oil or replaced with a new item.

ELECTRICS

W123s carry very little in the way of gadgets (on a lot of cars, electric windows and maybe air conditioning are the most exotic toys you’ll find) so the electrical system is little more than that required to make the car go and to work the various lamps. Most problems are due to poor earth connections with the body due to surface corrosion or life-expired connectors. After 30-plus years, the wiring in the engine bay can get brittle from heat and start to break down internally even if the insulation looks good. This will lead to fuses popping for no apparent reason but following the circuit diagram will allow you to trace any troublesome components.

The highest bit of technology in a W123’s electrical system is the solid-state ‘spark controller’ which controls the electronic ignition system. This is usually a ‘it works or it doesn’t item which dies when one of the internal components gives up, although misfiring under load and hard starting can be the first signs of trouble. These units can be repaired or replaced for around £100.

The seats on these cars are extremely comfortable but sourcing replacement soft furnishings can be difficult. Whether petrol or diesel, the engines on these cars can go on forever. The diesel W123 estate was regarded as a workhorse.