DB at 60 The definitive Aston Martin celebrated. In search of DB. Celebrating 60 years of the DB4, we drive a Series V in the tyre tracks of former Aston boss David Brown, tour his business empire and meet grandson Adam. Words Sam Dawson. Photography Jonathan Jacob. ‘It was an assertive car for newfangled motorways, for leaving Austin A40s shuddering in its three-figure wake’ We take an Aston-Martin DB4 series V on a Yorkshire pilgrimage to discover more about David Brown. In search of ‘DB’ To celebrate 60 years of the Aston Martin DB4 we take a Series V example to Huddersfield on the trail of its creator, Sir David Brown.

Crosland Moor, just outside Huddersfield, seems like a strange place to find an airfield. Contained by the Pennines rising to the West and the outer reaches of the city’s suburbs to the East, there’s no control tower, its runway is short and it’s home to more horses than aeroplanes. Today, an Aston DB4 sits waiting, its engine thrumming deeply, parked across a trio of curious stripes formed of white pebbles set in the old tarmac outside Crosland Moor’s only hangar.

The stripes are one of the few clues to the significance of this wind-frozen place. They mark out the wheel tracks of G-ARDH, a Riley-built De Havilland Dove – a business conveyance of the immediate pre-Learjet epoch, relatively enormous for its era. Sir David Brown’s plane.

In 1946, as his industrial empire boomed in the desperate post-war ‘export or die’ years, Brown decided he needed a quicker way to travel between his homes and the various outposts of his business, and turned a piece of land he’d used since 1936 for stabling horses and testing prototype tractors into an airfield. A few months later, Brown made the business acquisition that would define him – he bought Aston Martin.

My awaiting DB4 dates from 1962, and represents the ultimate evolution of the first Carrozzeria Touring-styled Aston Martins, a decision brought about after Brown rejected the Frank Feeley-penned in-house proposal for the DB MkIII’s successor. By 1962 the DB4’s roofline had been altered to yield more headroom, making it more comfortable than earlier cars. Once my knees have negotiated the bottom of the vast wood-rimmed steering wheel, the DB4 proves to be spacious, extremely comfortable with its deep padded leather seats, and remarkably ergonomic for its era.

The year this car was built at Newport Pagnell in Buckinghamshire, Brown was living at Durker Roods, a grand country house on the hill overlooking his gear works in Meltham, not far from Crosland Moor. It’s easy to imagine Brown stepping from the cockpit of the Dove – despite its luxurious rear quarters Brown preferred to pilot it himself – and into the cabin of a waiting DB4, perhaps delivered to the airfield from Durker Roods. The house is my ultimate destination today, but first I’m heading for a place in the Pennines which goes a long way to explaining why a Yorkshire tractor tycoon decided to stamp his influence all over a Buckinghamshire sports car manufacturer.

The DB4 acquits itself well on these bumpy country lanes. The odd pothole occasionally snags the sharp rack-and-pinion steering, but the sheer weight of the car flattens most of the road’s surface imperfections into submission at low speeds. Out of Blackmoorfoot and onto Slaithwaite (pronounced ‘Slawit’) Road, I build up to fast cruising speed. The DB4’s directional stability would’ve been a revelation in the early Sixties, that steering feeling reassuringly solid in a world of vague worm- and-roller setups directed by alarmingly flexible plastic helms. It’s an assertive-feeling car, for pulling out into the overtaking lane of a new-fangled motorway, authoritatively stamping on the accelerator and leaving rows of shuddering Ford Populars and Austin A40s agog in its three-figure wake.

The DB4 not a quiet car, curiously. In fact in the context of the late Fifties it’s strangely hard to place. At £4000 in 1962 it was twice the price of the more overtly luxurious Alvis TD21 with its polished wooden dashboard and whispering engine; but it wasn’t a supercar by the standards of the time either – it was priced in Ferrari and Maserati territory but was markedly slower and heavier than the 150mph Italians. Then again, by this point the DB4 range had spawned the GT and Zagato variants, so perhaps it merely had nothing to prove. That said, although it’s clearly made with the robustness of one of the Victorian factories around here, it’s not a luxury car – it’s relatively noisy, not particularly opulent and quite hard work to drive. Aston purists will hate me for saying this, but the cars it reminds me most of are the BMWs of the late Fifties, all straight-six torque, hefty build quality and a hint of race breeding overridden by a need to traverse the Autobahn at speed. And then, as I pass Meltham golf course, signal right and start to recall Aston’s early history, the reason becomes clear.

The road south of the village of Holme has several names. Officially it’s the A6024, but everyone knows it as the Woodhead Pass. Heralded by warning signs directing HGVs away towards the friendlier, straighter A628 and A635 and lined with tall reflective posts so the road can be picked out in deep winter snows, it’s a rare British equivalent of the dramatic Alpine passes that played host to the Mille Miglia and forged the reputations of Maserati, Mercedes and Alfa Romeo in the Twenties.

Back then, Brown knew this road as Holme Moss Hill. In 1927, he oversaw the build and installation of an Amherst Villiers supercharger for Raymond Mays’ Vauxhall racer. Mays was due to come to Huddersfield to test the car, but was delayed by a day. Keen to see if it worked, Villiers asked Brown to drive the car in Mays’ place. His pace on the hill impressed Villiers to the point of shock. When he arrived to test the car himself a day later, Mays was unable to match Brown’s times over the Pass.

We all have our favourite roads, and Brown was no exception – the Woodhead was his. As a young apprentice he’d learned racing skills on the motorbike he used to commute on by riding the Pass, and when his father Frank forbade a career as a racing motorcyclist with Douglas in 1921, David built his own special, based on a US-built Reading-Standard V-twin, and entered hillclimbs secretly. Each hairpin bend, blind crest and esses complex of the Woodhead was the young Brown’s test track. By the time the Mays-Villiers Vauxhall arrived in Huddersfield, Brown’s mastery of the Pass made him as good a test-driver as most professional racing drivers. On meeting the first hairpin, the DB4 feels alarmingly stubborn, not compliant enough to take on a road like this at speed. The steering is extremely heavy, although the wheel’s large rim does alleviate it slightly. Given the direction luxury cars were taking in the early Sixties, drawing inspiration from America with power steering becoming more common, it feels against the spirit of its era. But concentrate on making smooth progress, and the sense of immense heft starts to convey something more crucial – traction. There’s a firm surefootedness to its demeanour as it tackles the Woodhead’s hairpins, giving me the confidence to press on a little harder even though remnants of ice still glimmer on the shaded edges of the road. The wheel may be heavy but it’s precise.

You direct the DB4 through small inputs rather than the dramatic twirls demanded of a contemporary Mercedes-Benz 300 SL. The live rear axle is firmly tied down with radius arms and a Watt linkage, rather than the SL’s alarmingly wayward swing- arms. Perhaps what you paid for in a DB4, then, was precision. Its body control is superb compared to most late-Fifties and early- Sixties opposition. Rival Maseratis roll alarmingly in tight bends, but the Aston’s rear hunkers down neatly like that of a Nineties BMW M3 when tackling challenging roads, meaning you can feed in more throttle more often. It’s an intelligent use of power.

I’m hunching over the wheel like a pre-war racer, steering with the whole of my upper body rather than detached and lazily with my fingers. Adopt this vintage mindset, and you can hear David Brown speaking to you through the DB4. Everything about it has been honed with an industrial engineer’s attention to detail. The lever of the David Brown-designed gearbox wrist-flicks across the gate with metalled precision, like the control lever on a lathe, while the twin-cam straight-six snorts like a giant Lotus Elan engine taken an octave lower, crackling through the cabin on the overrun. It’s precisely the kind of car a respectable industrialist who’d led a rebellious, motor-racing youth would design.

It’s also a car that hints at Aston’s future direction as the consummate modern grand tourer. Big GTs in the early Sixties were still a nascent species, still unsure as to whether to embody ponderous yet long-legged Alvis-like luxury, embrace new convenience technology like the Buick Riviera, or focus entirely on rapid race-bred ground-coverage with a garnish of leather as per Ferrari. The DB4 confidently occupies a then-uncontested middle ground, handling almost as well a Ferrari while accommodating like an Alvis. It’s a role Aston flagships have fulfilled ever since – always more spacious than supercars, never really committing to the two-seater ethos, managing to still be genuinely luxurious while still being cars for people too young and sporty at heart to submit to a chauffeur-driven Rolls-Royce.

I turn back, and head into Meltham via Acre Lane. Off to the left, hemmed in by railings protecting pedestrians from a Victorian mill race, is Meltham Mill. Established as a silk mill in the 1860s, this Victorian redbrick edifice lived a significant second life as Brown’s tractor factory from 1939 to 1988. In fact, his various businesses at their peak employed more people in the Huddersfield area than anyone else. Passing locals make spontaneous warm comments as they see the resting DB4. They love the car, but the man behind it inspires even greater affection. He safeguarded the livelihoods, education and health (this complex had an on-site surgery with full-time doctors) of entire generations.

With a deep boom, the DB4 powers its way around the tight left-hand first-gear hairpin and up the steep Huddersfield Road towards Durker Roods. Built in local stone and originally completed in 1878 for Captain Arthur C Armitage, it’s a luxury hotel nowadays, but in the early Fifties and between 1960 and 1964 this Victorian manor house was Brown’s principle residence.

As tyres crunch gravel it’s a forbiddingly Gothic yet welcome sight, a place that would happily inhabit an MR James novella yet with the promise of a warm fire on a freezing December day. I pull up, find a chair in the dark-panelled, high-ceilinged David Brown Bar, and await the arrival of a former resident.

TECHNICAL DATA FILE SPECIFICATIONS 1962 Aston Martin DB4 Series V

Engine 3670cc in-line six-cylinder, dohc, two SU HD8 carburettors

Power and torque 240bhp @ 5500rpm; 240lb ft @ 4250rpm / DIN

Transmission Four-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

Steering Rack-and-pinion

Suspension Front: independent, wishbones, transverse arms, coil springs, telescopic dampers. Rear:

live axle, parallel trailing arms, Watt linkage, coil springs, lever-arm dampers

Brakes Servo-assisted discs front and rear

Weight 1545kg (3406lb)

Performance Top speed: 141mph; 0-60mph: 8.5sec

Fuel consumption 16mpg

Cost new £4084

Classic Cars Price Guide £280,000-£500,000

{module Aston Martin DB4}

‘It’s easy to imagine him stepping from his De Havilland’s cockpit into the cabin of a waiting DB4’

‘Adopt the appropriate mindset and you can hear David Brown speaking to you through the DB4’

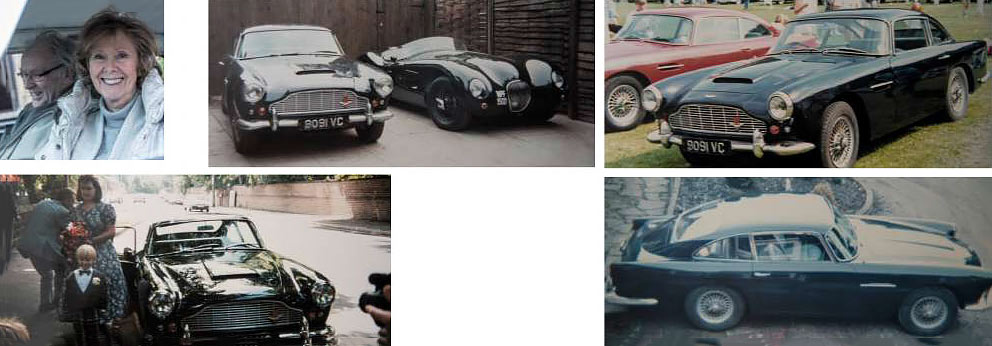

The owners: Paul and Jennifer Martin

‘I’d wanted an Aston DB4 ever since they were launched in 1958, but couldn’t afford one,’ says this car’s owner, former Merchant Navy engineer Paul Martin. ‘There was a step-change in the pricing between the DB MkIII and the DB4, from less than £3000 – still expensive – to more than £4000, which was a huge amount of money in the Sixties. But thankfully, they depreciated quite heavily back then.

‘It was 1971. I already owned a vintage Aston MkII – which I’ve still got – and I saw an advert for a secondhand DB MkIII for sale in London for £2000.

I drove all the way down there from Hull to have a look, but having test-driven it, it wasn’t quite what I was expecting. I was disappointed, and set off home back up the M1. But just outside London I passed Motorway Sports Cars, which had this DB4 on its forecourt for the same amount of money. I stopped, took it for a drive, and bought it there and then.

‘I’ve had it 46 years now and drive it in all weathers for all sorts of occasions, from club events to weddings. I’m not your typical Aston owner – well, not nowadays at any rate – in that I do most of

the work on it myself. There’s a lot of mystique surrounding how expensive they are to run and I certainly couldn’t meet most specialists’ prices, let alone afford to buy the car now; I can barely believe how valuable they are nowadays. It’s a fundamentally straightforward, solidly-built car with off-the-shelf parts such as a Salisbury differential, so it’s not difficult to work on if you know what you’re doing.

‘Given parts prices, it often makes more sense to repair than replace. For example, I once spent a while straightening the grille out after encountering a suicidal pheasant. It meant a few days in the garage with the grille in bits on the workbench, but given that a new one costs £1000, it was time well spent!’

Interview Sir David’s grandson Adam Brown recalls life at DB HQ during the Aston ownership years, and reveals some family-business secrets of his own. David Brown’s own MkIII – his grandson Adam – discusses childhood frolics at DB HQ, a stream of extravagant family conveyances and hidden talent that was never fulfilled. Words Sam Dawson. Photography Jonathan Jacob.

Adam Brown arrives not in his V8 Vantage, but a muddy Daihatsu Terios. He enters the bar dressed in the fatigues of a countryside ranger. Until 1990 he ran the David Brown gear works, but like his grandfather he feels a duty to the area and the land – he’s just been up on the moors repairing fences before the worst of the winter sets in. ‘This was the living room when I lived here,’ he remembers. ‘My grandfather would sit by the fire in his armchair, and there was a dining table at the other side. My bedroom was above this room; I used to play Cowboys and Indians on the staircase, and I learnt to swim in an indoor pool which was in what’s now the dining room. Across the hall was Sir David’s office, effectively the headquarters of the David Brown company, with a boardroom table at one end and a grand piano at the other.’

We settle at a large dining table by the window, overlooking the courtyard where the family used to play tennis – a sport at which Sir David excelled, playing competitively well into his eighties. ‘We used to fly into Crosland Moor in the De Havilland Dove from Buckinghamshire, where he had his farm. The plane functioned as both executive transport and family taxi; he also used it to fly the family down to the South of France to spend summer holidays aboard Astromare, his yacht. There was a very high personal tax rate back in 1960, so everything was technically owned by the company including the cars. David didn’t own a particular DB4, but would test-drive cars taken straight off the production line so he’d always have an Aston Martin to hand. My father, also called David, had his own DB4, as didmy Aunt Angela.

‘Naturally, my grandfather was one of the very first people to drive a DB4. Chassis engineer Harold Beach had been awake all night finishing the first prototype, which he took down to David the next morning at his Buckinghamshire house. He wasn’t a man given to displays of emotion, but his words to Beach after that first drive were, “This is a very promising motor car.” That represented high praise from him – he was an engineer first and foremost.

‘He’d actually designed and built his own car without his father’s knowledge, devising it in his bedroom and requisitioning parts including engine blocks from the foundry as he completed his apprenticeship in each part of the family business. David’s defence was “well, I’ve been round the whole factory!” and Frank was furious. But he knew when it was time to step back and focus on the business at large, which is why he preferred to delegate to quality engineers like Beach, Claude Hill and Tadek Marek.

‘The DB4, however, was his first Aston, the first where each aspect had been directed by him. When he bought Lagonda in 1948, he did so to access the WO Bentley-designed engines, so the early DB Astons were essentially the result of two different companies, but the DB4 had been designed from scratch. He wanted a car that could do 140mph, and he said he wanted “a comfortable conveyance that could excite me” – and as I said, he never usually expressed emotion. The later DB5 and 6 became more conventional gentlemens’ expresses of their era, more luxurious, but the DB4 was exactly as Grandfather specified.’

Outside of Aston Martin, Sir David is best known for the tractors that bore his name, but even this came about as a result of the rebellious spirit that saw him sneak his special out of the factory. ‘He took the Group into the tractor business against his father’s wishes,’ Adam explains. ‘The direction of the business really changed when new gear-making technology from the US became available, which helped with the war effort too. After the war, the enormous pressure of supplying the Army came off his shoulders, and he could afford to buy Aston Martin. He’d always tell you these things before ever talking about Aston Martin; it was important for people to know where he’d come from. The reason why he put his initials on the cars was simple – he’d never been involved in a business that didn’t have his name on it somewhere. ‘The end of his ownership of Aston Martin was a sad time.

In 1971 Rolls-Royce went bust, which had been unthinkable, and suddenly all the banks wanted to know which engineering businesses they had – and Lloyds had us. We’d just built a new factory and both Aston Martin and the tractors were haemorrhaging money so we had to sell both. The tractor business sold well, but Aston Martin went to Company Developments – a bunch of asset-strippers – and nearly went bust itself.

‘After that he felt he had to move on. In 1977, in the wake of the nationalisation of our shipbuilding company, Vosper Thorneycroft, he moved to Monte Carlo in disgust. He renounced everything to do with England in the Seventies and Eighties. The David Brown Group had done a lot of good. At its height we employed 14,000 people. By the time I joined the gear business in 1979 that was down to 5000, and by the time I left in 1990 we employed just 1200. Sadly, that’s how engineering in this country has gone.’

However, in 1993 Ford and Walter Hayes approached Brown when devising a new straight-six Aston GT in the mould of the old DB4. ‘He gave his blessing to the project, and the permission to call it the DB7,’ Adam recalls wistfully. ‘He was delighted to be involved again.’ Sir David passed away only a few months later. ‘But at the end of the day he was an engineer. That was the most important aspect of his personality. Sports cars are how engineers like to test their work, subjecting them to stresses and strains. Nothing challenges engineering quite like racing.’

After today’s exertions, I’m getting a sense of another David Brown, private to the point of hidden – the frustrated racing driver. ‘Possibly’, says Adam, sitting back in his chair after some thought. ‘Perhaps he raced vicariously through his drivers. He was certainly no stranger to the paddock during the successes of the Fifties, and very supportive of his team managers. He wasn’t the type to go up to Stirling Moss and tell him what to do, but as with the engineers he’d enlisted to build his cars, he had John Wyer to do that for him! But yes, he could have been a racing driver. He took to any sport naturally, including polo which he only started playing in his forties. He was a very smooth driver, but very, very fast – my abiding memory of him will always be being driven in his purple Series 1 Lagonda V8 at 140mph up the M40, coming up fast behind motorists who thought they were going fast at 70. I’ve no doubt that had he been allowed to race when he was younger, he would’ve been up there with the greats.’

Thanks to Anthony Oade, Aston Martin Owners’ Club (amoc.org), Crosland Moor Airfield (croslandmoor-airfield.co.uk), Durker Roods (durkerroodshotel.co.uk)

‘His words after driving the very first prototype DB4 were “this is a very promising motor car”’