Great White Threat. Designed in Britain and clothed in Switzerland, this unique Beutler-Healey was built to take on Italy’s finest GTs in the toughest race of all – the Mille Miglia. Words Sam Dawson. Photography Jonathan Jacob.

Extreme Porsche 356B resto

Great White Threat Tearing through Buckinghamshire in the unique Beutler-Healey, designed in Switzerland to take on late-Forties Italian Mille Miglia exotica. Beautiful brute – the Mille Miglia Healey built to take on Alfa Romeo and Lancia

Few words in the world of motor sport carry quite so many connotations as garagiste. Often attributed to a frustrated Enzo Ferrari in the Sixties as he watched his thoroughbreds humbled by British cottage-industry teams using major components drawn together from various sources, it conveys a combination of elitism and jealousy; resentment at the loss of an older, grander state of affairs.

But today, I’m taking in the sweeping, bulbous lines of the Beutler-Healey Coupé; physical evidence that this sentiment took root before Formula One existed. The first postwar garagiste to provoke the ire of the Italian engineering aristocracy was not John Cooper or Colin Chapman, but Donald Healey. The slighted parties were Alfa Romeo and Lancia – by contrast, in the late Forties Ferrari was an upstart, albeit one with Alfa pedigree. This flamboyant grand tourer I’m about to drive in the aristocratic locale of Woburn was devised by Pietro Nessi, a Lucerne-based Italian dealer intending to sell Healey’s cars on Alfa’s doorstep, and it must have seemed the very embodiment of the British threat to Italian engineering.

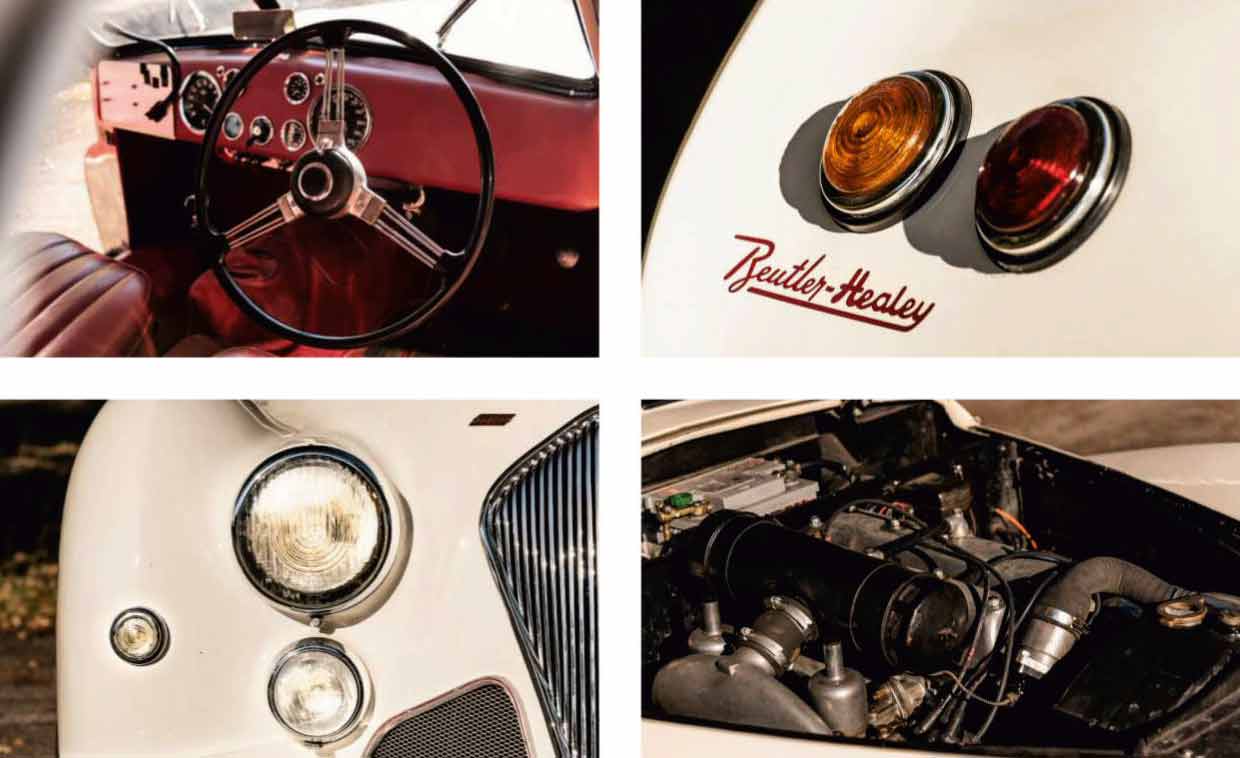

Its design, courtesy of Beutler of Thun, Switzerland, almost apes Pinin Farina’s Alfa 6Cs and Lancia Aprilias too. It’s an unusual piece of design. My initial response is one of rapture – the compound flow of its wings, the curving roof and the perfectly-placed headlights nestling between the wings and bonnet recall French art-deco masterpieces and Italian concours d’elegance showstoppers alike. But then minor details start to unpick it.

‘The Riley twincam shatters any Latinate civility with a robust British thumping’

Its proportions aren’t quite truly elegant – the slightly oversized three-piece grille results in a big jutting chin, the point where the trailing edge of the front wing meets the swell of the rear is a little too elongated for balance, and the tail is extremely long. Looking at Beutler’s back-catalogue, it does seem this Swiss carrosserie was prone to over-bodying smaller cars, especially Volkswagens and MGs. Its favoured sweeps and flourishes were drawn from more luxurious chassis like Bentley and Bugatti; this Healey isn’t quite long enough to carry it off. But it wasn’t just built to look pretty. In a war-shattered late-Forties Europe, the hottest crucibles of motor sport were epic road-rallies held at race speed, the ultimate example being the Italian Mille Miglia.

Indianapolis 500 aside, it was the first blue riband event to be revived after the hostilities, predating Le Mans’ return by two years. And it was considered a race for thoroughbreds. Pre-war, it had been dominated by the likes of Alfa Romeo, Delage, BMW and Talbot-Lago.

Because the Sporting Commission of Brescia arranged the race for 1947, it appeared the status quo would not just be upheld, but garnished with patriotic fervour. With the French and German grande marques in ruins, the competition was dominated by Alfa Romeo 8Cs, Cisitalia 202s, Lancia Aprilias and all manner of Fiat 1100Ss modified by Italy’s burgeoning coachbuilding and race-engineering sector.

The 1947 Mille Miglia wasn’t just a triumphant return of one of motor sport’s greatest spectacles, it also coincided with the beginning of what would become the Italian postwar economic miracle. Marshall aid from the US soon arrived, invigorating these very industries that treated the Mille Miglia as a glamorous international shop window in which to display their various visions for the future of the sports car.

But something was stirring in Britain too. A scant six months after VE Day, racer-engineer Donald Healey published a treatise in The Autocar, ‘Specification for Performance’, in which he drew upon prewar motor sport experiences to outline a recipe for a new kind of sports car. Three quarters of the document was dedicated to chassis design, and the creation of handling neutrality.

Healey discussed minimising air resistance and even the use of spoilers at greater length than he did engine technology. He saw no inherent advantage in designing a car as a completely in-house thoroughbred. So far as the power under the bonnet was concerned, Healey prized rugged short-crank big-valve four-cylinders for their dependability over and above complex and elaborate V8s and V12s, name-checking the Riley twin-cam four-cylinder as a perfect example.

In his final warning-shot paragraph, Healey stated that ‘the sports car should shine in the big international rallies, apart from [circuit] racing. There again it was gradually becoming apparent before the war that the ordinary car, or some slight modification of the ordinary car, had such a high performance as to be almost, if not quite, on equal terms with its rival.’

In retrospect Healey was prophetic, his description predicting almost every future British sports car from a Triumph TR to a Lotus Esprit. Within two months, Healey’s idealised specification had progressed from an idealogy to the design stage. A year later the car was available, in Westland roadster and Elliott saloon form, primarily for export because of the postwar recapitalisation drive. And Healey sought to prove it in the biggest international rally of them all – the Mille Miglia.

In the midst of postwar austerity and strict export-or-die policies aimed at maximising national productivity in desperate times, the British public would only know about Healey’s sporting success if it read the motoring press in 1947, but that success was significant. Driven by none other than Count Giovanni Lurani, creator of the FIA’s GT racing rules, a Healey Elliott saloon became the first-ever British class-winner of the Targa Florio. A week later, father-and-son team Donald and Geoffrey Healey drove the first British class-winner at the Mille Miglia since the MG K3 Magnette that Lurani had steered to victory in 1933.

There were four Healeys entered in the 1948 Mille Miglia, but only three actually arrived in Brescia. The fourth – this car – was still in an incomplete state. Nessi had commissioned six bodies from Swiss coachbuilder Gebrüder Beutler & Cie, which built Porsches at the time, to clothe chassis he’d bought from Healey – five dropheads and this coupé. But the company took too long to finish this first car in time for the race.

Nessi’s run of Beutler-Healeys was completed in the aftermath of the 1948 win, and played a very different initial role. It’s believed this car, originally finished in blue, made its public debut not in competition but on Ernst and Fritz Beutler’s stand at the 1949 Geneva Motor Show.

Its finer details speak of ruggedness rather than overt panache. Whereas a Farina design of this era would have pencil-thin, flush-fitting pop-out doorhandles and its interior would have been a concoction of sculpted Bakelite, glossy painted metal, flashing chrome and steel, the Beutler-Healey has chunky parts-bin fitments and a hard-wearing, high-quality leather slab of a dashboard. It’s businesslike, and in keeping with Healey’s ethos typical of Fifties and Sixties British sports cars to come.

But bear in mind that this car cost £3000 in 1948. Cheap when compared to a Ferrari 166MM at an astronomical £6000, but that ran in the Sports Prototype class. The Touring-class Pinin Farina-bodied Alfa Romeo 6C 2500 Freccia d’Oro, by contrast, was £1988, spread its two and a half litres across more cylinders, and was much more elegantly finished. But as Healey predicted, the Alfa could be fragile. By contrast, everything about the Beutler- Healey feels rugged and burly. And then, as I glance backwards, reflecting on the comfort of the driver’s seat, I see a little island of elegance – the rear seating area is an exquisitely-trimmed and intimate cocoon of maroon leather, thick carpets and fawn headlining. Just as I think I’ve got the measure of this car as a brutish immediate postwar camion de plus vite successor to the Bentleys of the Twenties, it continues to surprise.

Turn the ignition key, hit the starter button and the 2.4-litre Riley twin-cam thunders into life, shattering any Latinate civility with a robust British thumping. First gear on the unsynchromeshed ’box is just for pulling away and low-speed manoevering, so I jump quickly into second and allow the torque to lunge the car forward. Gearchanges have to be timed very carefully, but the Healey soon impresses as an excellent, relaxed cruiser, the twin-cam quietening considerably in top gear and from 40mph upwards. Brakes, reassuringly, are excellent, as progressive as Healey’s treatise in The Autocar promised.

But what of the handling?

Unfortunately, a driving position that initially seems way ahead of its time in its reclined, long-legged ergonomics almost proves to be its undoing. My arms are outstretched but the steering is extremely heavy, putting strain on the forearms rather than the shoulders. There’s also a lot of slack in the wheel – there’s a full eighth of a turn before the front wheels respond, so you have to think ahead when driving the Healey, and start turning the wheel before you actually enter the corner. Nessi must have been both strong and brave, bearing in mind he would have been averaging 70mph on the Mille Miglia.

Once the car’s in the bend though, it’s faithful. It needs a firm hand, holding a steady line, but there’s an immense sensation of grip, eliminating both understeer and oversteer with solid traction. The ride is a bit odd though and I can only liken it to an upsized, heftier Morgan Plus 4. Both ends of the car are suspended by trailing links, but while the independent fronts float over bumps and potholes, the firmly sprung rear axle thuds sharply, sending shocking jolts up my spine.

As the 1949 Mille Miglia approached, Nessi’s now-completed Beutler-Healey reappeared on the entry lists, but the heavily-subscribed Touring class clearly rattled the Italian organisers, not least with its Britishness – Count Lurani was driving a new Bristol 400, and alongside the Healeys was a significant Frazer Nash contingent. Italian motoring journalists protested. Auto Italiana’s Franco Degli Uberti, concerned by the potential of the Touring class to slow Ferrari’s sports-prototypes down, pondered, ‘Will we block the roads of Italy for 48 hours or more to allow all those who want to vent their need for speed to do so?’ Even his fellow journalist Corrado Filippini, an FIA board member who’d helped codify the GT racing regulations with Lurani, openly admitted with some regret that the 200-car homologation-run stipulation for the Touring class carried ‘a risk of favouring cars built in other countries’.

This combination of threat and national pride may well have contributed to the confusion that caused this Healey to elude marque experts for decades.

The Sporting Commission of Brescia, possibly in response to the Beutler-Healey’s one-off coachbuilt nature, put Nessi’s car in the Sports class, where it would have been easily trounced by the likes of Clemente Biondetti and Felice Bonetto in their works Ferrari 166MMs. Nessi alerted Donald Healey, who in return sent the build details for the Elliott saloons to confirm the Beutler as a special body on a Touring-class-homologated chassis. The Sporting Commission duly relented, but as a result the Beutler ended up incorrectly described as a Elliott saloon in all the race’s documentation.

Cameras were rare commodities in 1949, and with the record entry thanks to the permissive rules of the Touring class, not every car was photographed. Nessi’s Beutler slipped through the race uncaptured. With just incorrect documentation to go on, Healey authorities looking to track down this missing Mille Miglia car years later assumed they were looking for a familiar Elliottbodied saloon, rather than this old motor show car, hiding unseen in an American collector’s garage.

This exciting race was even faster and more extravagant for 1949 because the route returned to its original thousand-mile length yet avoided running through the centres of Turin and Milan. Sadly, lack of record-keeping during the race means that what ended Nessi’s race is unknown. The records simply state ‘DNF’, although it’s unlikely he crashed.

The car has only undergone light restoration; the bodywork is completely original and shows no sign of having been repaired. Mechanical failure is a more likely cause, although it must have been something very serious given that Lurani nursed a broken Panhard rod and still managed to win the Targa Florio in his Elliott. But 1949 was still a great year for Healey, confirming the worst fears of the Italian press. For much of the race it seemed Alfa Romeo could fight back the foreign invaders in the Touring class, the 6C Freccia d’Oro of Franco Venturi and Consalvo Sanesi leading almost throughout. But as Brescia’s finish-line loomed, the fragile Alfa suffered irreparable mechanical failure. Venturi and Sanesi could only stand and watch as the Elliott of Geoffrey Healey and Tommy Wisdom thundered by in the dust, the solid reliability of its Riley twin-cam securing Healey the Touring-class crown for the second year running. The British had made their mark. The following year would be even worse for the Italians – even though the Sports class was still a Ferrari lockout, Touring was Jaguar-dominated – and piloting an XK120 was none other than Clemente Biondetti.

But what of Nessi and his Beutler-Healeys? Just two others were built following the initial run of six, only one a coupé, which took to the stand at the Turin Motor Show. But coachbuilt Healeys were about to become a distant memory for dealers – the Austin-Healey 100 was in development. And unbeknownst to Nessi at the time, in 1957 the 30-year-old motor sport institution of the Mille Miglia would come to a tragic end too. A new era of mass production was dawning, and even the aristocratic Alfa Romeo had to embrace it, meeting Healey head-on with the first of a new generation of Spiders. Ferrari was soon fighting garagistes in both sports-car and Formula One racing. A new battle between Britain and Italy was underway, on European racetracks and American showrooms alike, but in retrospect we can see this remarkable coachbuilt coupé as one of the first shots to be fired in a war that still rages today.

‘The Riley twincam shatters any Latinate civility with a robust British thumping’

TECHNICAL DATA FILE SPECIFICATIONS 1948 Beutler-Healey

Engine 2443cc in-line four-cylinder, OHV, twin camshafts, two SU H4 carburettors

Max Power 106bhp @ 4800rpm / DIN nett

Max Torque 136lb ft @ 3000rpm / DIN nett

Transmission Four-speed manual, rear-wheel-drive

Steering Worm and roller

Suspension Front: independent, trailing links, coil springs, lever-arm dampers. Rear: live axle, Panhard rod, trailing arms, coil springs, lever-arm dampers

Brakes Girling hydraulic drums front and rear

Weight n/a

Performance Top speed: 104mph; 0-60mph: 14.6sec

Fuel consumption 21mpg

Cost new £3000

Estimated value £500,000

OWNING A BEUTLER-HEALEY

Says Healey collector Warren Kennedy of his unique Beutler, ‘I didn’t realise I owned the so-called ‘Mille Miglia Elliott’ – although for obvious reasons it eluded me for years because it wasn’t actually an Elliott and no-one thought to take a photo of it in 1949!

‘I found it in Canada, and it had spent most of its life up to that point in a collection in the US. I didn’t know much about it, but it was only once I bought the files from Healey’s old experimental department at auction that I realised that it was Pietro Nessi’s elusive Mille Miglia car.

‘At slow speeds it’s very heavy, but the faster you go the better it becomes. It’s a tough and reliable thing too – it had a sympathetic light restoration by Sam Stretton in the Nineties. It’s had no significant work since, yet it continues to function.’