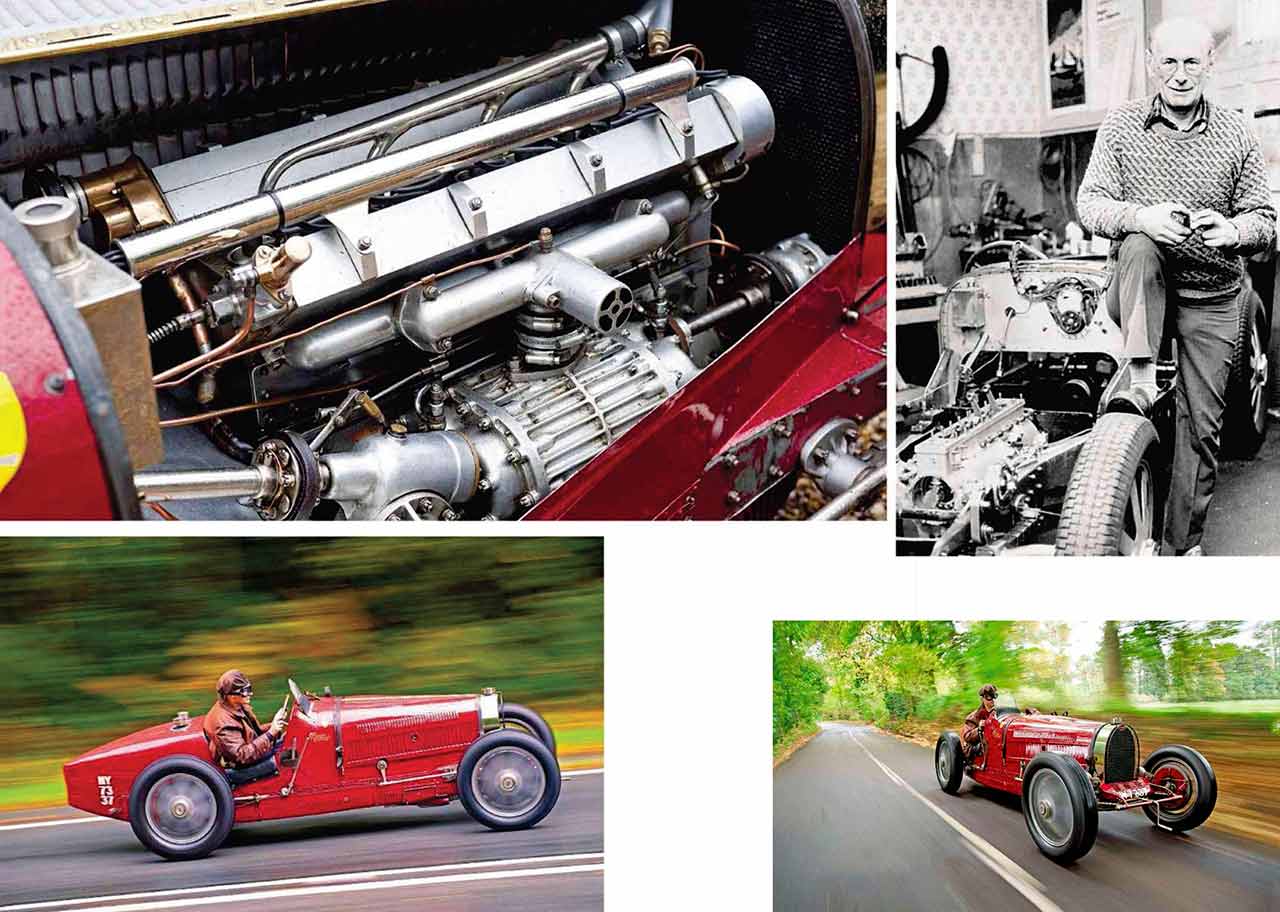

Bugatti Type 51 ‘Squeeze the throttle and the Bugatti lunges forward with a snarl’ On-road in a proper grand prix car. Bugatti Type 51 Living like a Lord …which in this case means getting wet and dirty at the wheel of a Type 51 Bugatti – and thoroughly enjoying it, just like its late owner, Lord Raglan. Words Mark Dixon. Photography. Paul Harmer.

There’s a saying among journalists that you should never let the facts get in the way of a good story. That’s why I’m not too bothered whether it’s true or not that when the First Baron Raglan had to have his arm amputated at the Battle of Waterloo, he reputedly asked for it back so he could retrieve his wedding ring. The First Baron didn’t have much luck, militarily speaking. He oversaw the disastrous Charge of the Light Brigade during the Crimean War and died not long afterwards from dysentery. One hundred and fifty-five years later his direct descendant. Fitzroy John Somerset, has just passed away in altogether more peaceful circumstances, and that’s why his famous Bugatti Type 51, a car he restored and owned for 30 years, is about to come to market. It’s one of the best-known and certainly most enjoyed Type 51s in existence, and you can’t talk about the car without mentioning the man: it will always be known as the ex-Raglan 51′.

While he didn’t have such an eventful military career as his predecessor, Lord Raglan, as the Fifth Baron was more usually known, was a classic example of the slightly eccentric but intelligent and decent hereditary peer that the British do so well. He was the third of only three patrons of the Bugatti Owners’ Club to date – after Ettore Bugatti himself, and Earl Howe – and he was also a proper hands-on enthusiast, always willing to get his hands dirty in the name of vintage cars. Literally so, for giving his maiden speech in the House of Lords in 1965, he began: I am sorry that I have only just arrived. I have suffered a series of misfortunes with my motor car; I am covered in oil and quite flustered, so I hope your lordships will excuse me.’

After an hour or so at the wheel of the Type 51, on a drizzly day in late autumn, I ‘m not covered in oil – a little bit of petrol, maybe – but my coat will never be quite the same, having been bombarded with dirt and road grit thrown up by those distinctive alloys. It’s a small price to pay for the chance to drive one of Bugatti’s greatest cars, its last truly successful racing car before this relatively small independent company had to yield to the state-backed resources of the Italian and German giants.

‘Squeeze the throttle in first gear and the Bugatti lunges forward with a snarl; there’s barely time to catch your breath before grabbing second, then third’

Appropriately enough, the Type 51 is presently in the care of Nick Benwell’s Phoenix Green garage – a VSCC institution, where Jenks’ used to lodge – and to make sure it’s up to scratch we have reinforcements in the shape of Frazer Nash – BMW guru Mark Garfitt, who was a friend and neighbour of Lord Raglan and knows the car intimately. Mark helped in the latter stages of the car’s restoration and accompanied Lord Raglan on an epic European road trip in 1981. Later, over a post-drive pint in the adjoining Phoenix pub, he tells me: ‘We drove about 1500 miles and the only problem we had was a sunken carburettor float, which we repaired with a dab of Araldite in a hotel room beside Lake Como.’

Lord Raglan usually ran the car on methanol, but for practical reasons it’s back on petrol today. A few pumps on the Ki-gass primer, a swing on the starter and it explodes into life – there is absolutely no doubting this is a grand prix car; it’s merely loud at idle but a blip on the throttle sends the revs soaring instantly with a piercing shriek. Lord Raglan modified the supercharger to give an estimated 250bhp on methanol, so it’s probably still good for 180bhp on petrol, which gives a pretty healthy power-to-weight ratio in a car that tips the scales at roughly 780kg – the same a s a Lotus Exige.

That engine is basically a twin-cam version of the singlecam straight eight used in the iconic Type 35, the twin-cam head and valvegear unashamedly cribbed from the American Miller engine – Ettore had swapped a trio of Type 43s for a couple of Miller-powered cars in 1929, in a deal with US racing driver Leon Duray’, aka George Stewart. Otherwise the car is broadly similar to the Type 35: easiest way to distinguish a Type 51 is by the twin filler caps on the rear deck, although the hole for the supercharger relief valve on the Type 51 is also much lower down on the offside bonnet than on a Type 35.

The cockpit layout is very similar, too, but with the magneto poking through the dashboard on the left-hand side rather than in the middle of the dash, as on a Type 35. And the footwell is similarly cramped, requiring narrow-welt driving shoes or – for the less sartorially prepared – no shoes at all. At least the pedals are in the conventional order, and high enough off the floor to prevent your socks from soaking up the slick of rainwater, oil and petrol that tends to gather there after a decent-length drive.

There is proper grand prix history somewhere in this car’s early life – we’ll come to that in a moment – which explains the heavy-duty hand pump on the riding mechanic’s side, installed to resupply the engine with oil during a long race. Of more immediate concern are the outside-mounted handbrake (no fly-off ratchet on this race car; you want to park up, you stick a lump of wood under a wheel) and the similarly external gearlever, which snakes inside the bodywork to operate through a delightfully machined open gate.

Now that a little heat has permeated that 2300cc straight eight, you can point the 51’s slender prow at the open road – in this case, the busy A30 that runs past the Phoenix Green garage. Ease that ice-cold, highly polished gearlever towards you and into first, let up the short-travel clutch, and the Bugatti slips neatly into the traffic stream, leaving faint rooster tails of spray behind it. Mad dogs and Englishmen – or, in this case, one mad Englishman and an old car…

Squeeze the throttle gently in first gear and the 51 lunges forward with a snarl; there’s barely time to catch your breath before grabbing second, then third. The shift pattern is unconventional for modern drivers, with first on the left and towards you. second straight forward, third across to the right and back, and fourth forward from that; but after a couple of minutes it becomes second nature. On the day of my drive, the engine idle speed is set slightly too high and each engagement of first gear from rest brings a graunch of protest from the cogs: the way to get around this. I discover rather too late in the day, is to give the throttle a sharp little prod immediately beforehand, which, if you’re lucky, will confuse the piston in the single SU carburettor and cause the revs to falter momentarily, during which you can sneak the gearlever into first while it’s distracted. Some of the time, anyway.

This quirk apart – which would easily be cured by adjusting the idle speed – the Bugatti gearbox is a delight, and a revelation to anyone who’s ever struggled with a Bentley. On the move, you can shift gears almost as fast as you can move your hand, and on downchanges it’s remarkably tolerant of somewhat approximate double-declutches and throttle blips. You must be careful, in fact: the willingness of the engine to rev, and the slickness of the gearchange, can breed overconfidence, which will receive a nasty knock when you rush up to a junction and suddenly remember that cable-operated drum brakes, skinny tyres and wet roads are not a happy combination. The car is light and the brakes work fine – but only once you’ve cut through the damp that’s permeated the drums during your Toad of Toad Hall heroics on the open road.

The Bugattis steering response is sublime, naturally, and a skilled driver – one who is unconcerned by the £800,000-plus value of this particular car – can make very rapid progress indeed. Having once been subjected to a display of virtuoso drifting on wintry Herefordshire lanes by VSCC racer Geraillt Owen in his methanol-fuelled Type 35B, I’m accustomed to Bugatti performance, but I’d forgotten how civilised these cars are on rural back roads. The ride is flexible and civilised, allowing you to press on without fear of being jolted into adjacent ditches. Mention of the vulgar subject of money is a good cue to talk about this Bugattis particular history. What follows is the short version – for chapter and verse, see the entry in the Bonhams’ catalogue when this car comes up for sale at Paris in February.

It started life as chassis 51153 and engine 32, the first of a batch of five 51s built in April 1933. As a works car, it’s believed to have competed in the 1933 Belgian and Dieppe Grands Prix, driven by Rene Dreyfus to third and second places respectively. It may also have raced in the 1934 Monaco Grand Prix – it’s not 100% certain – in the hands of Pierre Veyron, the works driver whose surname has become familiar to every 21st-century schoolboy.

Then, in 1934, 51153 had a serious smash in the hands of its new owner, Giovanni Aloatti, on the Targa Florio. It was returned to Molsheim and may have been fitted with a replacement chassis. This is a pivotal moment in the car’s history, a s we’ll see. In late 1936 it was sold to British dealer Jack Lemon Burton, and post-war was heavily modified by owner Allan Arnold for competition use. A whole string of further British owners preceded its export to the USA in 1959-1960, where it again passed through the hands of several collectors. But the key transfer, from a historical point of view, was its sale by Bugatti collector Ray Jones to Jack’ Nuttle in 1967.

As sold, the Type 51 passed to Nuttle with chassis 256 – a much earlier Type 35 chassis, dating from mid-1926, and with 256’s matching gearbox and axles – but still retaining engine 32. This is where the story gets more complicated. The lower crankcase of a Bugatti engine is a substantial chunk of the whole unit and incorporates the four engine bearers, on one of which is stamped the all-important engine number. The lower crankcase of engine 32 was damaged, so Nuttle swapped it with Ray Jones for the lower crankcase of engine 20, which was in better condition. Jones then sold 32 s crankcase to Bugatti collector Uwe Hucke.

Nuttle spent seven years restoring his car, and it’s now in the Peter Mullin collection as 51153. But by 1979 Ray Jones had engine 32’s matching gearbox and back axle, which he sold to Lord Raglan, along with chassis 738. Raglan acquired 32’s lower crankcase from Uwe Hucke and restored the car over the next three years, doing much of the work himself. Although 51153 had lost its original body back in the 1940s, Lord Raglan was able to re-clothe it in mostly original Bugatti panels salvaged from Type 35s.

The key question is: after 51153 was crashed in 1934, was it fitted with chassis 256, an eight-year-old Type 35 chassis, or with 738, a much newer Type 51 frame Expert opinion, in the UK at least, suggests the latter is more likely and that 51153 has always been associated with 738 since at least its Allan Arnold days. The Bugatti Owners Club therefore lists the ex-Raglan car as 51153 with engine 32.

However, respected US Bugatti registrar Sandy Leith maintains that the Nuttle/Mullin car has the right to 51153’s identity on the grounds of continuous history. In practice, no-one seems to worry too much about which is right; both cars are well known and accepted within Bugatti circles.

How much value is placed on matching numbers’ varies from individual to individual, and indeed from country to country – Brits seem to care less about this than, say, Americans. Provenance is everything with competition cars, of course, but then racing Bugattis tend to be even more of a pick-and-mix of components than is usual. The sensible approach is to view this car exactly for what it is: a Bugatti that was restored to be driven and enjoyed, rather than tucked away as a museum piece.

Tech and photos

TECHNICAL DATA FILE SPECIFICATIONS 1933 BUGATTI TYPE 51

ENGINE 2262cc twin overhead-cam all-alloy straight eight, head cast integral with block, two valves per cylinder, single SU carburettor, Roots-type supercharger

MAX POWER c180bhp at 5000rpm on petrol; c250bhp on methanol / DIN (see text)

MAX TORQUE c129lb ft at 3900rpm on petrol: c170lb ft on methanol / DIN (see text)

TRANSMISSION Four-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

STEERING Worm and wheel

SUSPENSION Front: hollow-forged live axle, semi-elliptic leaf springs. Rear: live axle, reversed quarter-elliptic leaf springs, radius rods

BRAKES Cable-operated drums heat-shrunk into cast alloy wheels

WEIGHT c780kg

PERFORMANCE Top speed c140mph

‘The footwell is cramped, requiring narrow-welt driving shoes – Or 110 shoes at all. At least the pedal are high enough to keep your socks from soaking up the slick of oil and rainwater that gathers there after a long drive’

BUGATTI: A CENTURY OF ULTIMATE ROAD CARS

TYPE 18 Ettore Bugatti was barely out of his 20s when he created his first supercar’, a five-litre, chain-drive road-racer. Seven are known to have been built during 1908-1912, of which Black Bess, above, is the most original of the three survivors. We road-tested it in 2017 by Drive-my.

TYPE 35 Best-known of all the pre-war Bugattis is the Type 35, a grand prix car that could be driven on the road. Introduced in 1924 with a 2.0-litre straight eight, it evolved into the 2.3-litre blown’ Type 35B by the time production ended in 1931, superseded by the twin-cam Type 51.

TYPE 45 Bugatti made an unsuccessful attempt to take the Type 35 to another level by shoehoming two supercharged straight eights side-by-side in the same chassis and gearing them together. Only one Type 45 was built; the engines gave 250bhp but their weight compromised handling.

TYPE 53 One of the few pre-war Bugattis not to sport the traditional horse-shoe radiator, the Type 53 of 1931 was radical in its use of four-wheel drive – the first 4WD race car since the 1903 Spyker. Powered by a blown 4.9-litre straight eight, the Type 53 was fast but complex. Three were built.

TYPE 54 In his struggle to counter the might of the German and Italian state-backed race teams, Bugatti produced the Type 54 in 1931-1932. It had the big 4.9-litre blown eight’ and was heavy, but 54s finished first and second in the 1933 German GP, driven by Varzi and Czaykowski.

TYPE 55 Most handsome of all the pre-war Bugatti roadsters, the Type 55 was an amalgam of Type 54 GP car chassis with Type 51 twin-cam engine and. usually, Jean Bugatti-styled coachwork. With just 38 examples built, it was considerably rarer than its closest rival, the Alfa-Romeo 8C.

TYPE 57S If the Type 55 was the most handsome roadster, the most dramatic of all Bugattis was the Art Deco-style Type 57S and its supercharged sibling, the 57SC, Passing the rear axle through rather than under the chassis helped create a low, sleek look. Forty were made. 1936-1938.

TYPE 59 Radially spoked wire wheels distinguished Bugattis last traditionally styled Grand Prix car. which featured a 3.3-litre blown eight’ that gave 250bhp. Six or seven cars were made during 1933-1936; they were quick but marked Bugattis last hurrah as a works entry in major races.

EB110 GT The Bugatti revival came in 1991 when entrepreneur Romano Artioli launched the EB110 GT, a Gandini-styled supercar with a four-turbo V12 that gave a top speed of 212mph The 1992 SS (for Supersportl version, above, was lighter and even faster, at 216mph.

VEYRON Bugatti wont bankrupt in 1995 and was rescued by VW (VAG), who saw the value of a halo’ model that would be the fastest road car ever made. The 1001bhp Veyron was launched in 2005 and achieved as much notoriety for its price of С 1.3 million as for its 253mph maximum speed.