Vauxhall Prince Henry Godfather of sports cars. Pomeroy’s masterpiece. Malcolm Thorne gets to grips with a magnificent 1910 Vauxhall C-type. Hail the Vauxhall Prince Henry, Britain’s first road car designed for pure enjoyment. Malcolm Thorne gets the rare privilege of a proper drive. Photography Tony Baker.

HOW IT ALL STARTED Founding father: the Vauxhall Prince Henry is the genesis of the sports car.

Certain everyday objects are so ubiquitous, it can be a struggle to imagine an age where they didn’t yet exist. Think of the ballpoint pen or the sliced wholemeal loaf. To those of us, for instance, who occupy a world of oily fingernails, carburettors and owners’ clubs, there is nothing more ubiquitous than the Great British sports car. There was, of course, a time when such a concept had yet to emerge, but that idea is somehow puzzling. And to those with but a superficial knowledge of our rich motoring heritage, it’s maybe perplexing that the car widely considered as the prototype British sports model came from a marque better known today for mass-market hatchbacks. Ladies and gentlemen, meet the origin of the species: the Vauxhall Prince Henry.

The Vauxhall Iron Works – named after the London borough it called home – was founded in 1857. The company specialised in pumps and marine engines, but in 1903 it branched out into the avant garde world of the horseless carriage, offering a single-cylinder 5hp model with chaindrive and tiller steering. In 1905 the firm moved to new premises in Luton, and by 1907 it had been renamed Vauxhall Motors. A plethora of quality three-, four- and six-cylinder machines ensued, establishing the enterprise among the upper echelons of early British manufacturers until its acquisition by General Motors in 1925 shifted focus to more mainstream products.

A pivotal moment came during the winter of 1907-’1908 when, with chief engineer FW Hodges travelling in Egypt, a 25-year-old draughtsman called Laurence Henry Pomeroy convinced his masters that he could design a power unit for the Y-type that was set to compete in the 1908 RAC 2000-Mile Trial. His 38bhp 3139cc ‘four’ achieved its goal, the Luton car effortlessly beating a Rolls-Royce 40/50hp to take overall honours on the arduous event and cementing Pomeroy’s reputation as a gifted engineer, as well as Vauxhall as a maker of quality machines.

Further competition success followed on the 1909 Scottish and Irish Trials, and so in 1910 a three-car team was entered for the Prince Henry Trial – the Prussian event named after its patron, 48-year old Prince Albert Willhelm Heinrich, the easygoing and much-liked younger brother of the more authoritarian Kaiser Willhelm.

Those works cars had originally been intended to run an experimental engine featuring threevalve heads, but when bench tests revealed reliability issues Vauxhall opted for a tuned version of the existing 90 x 120mm sidevalve unit found in the production A-type. The chassis, meanwhile, was lower, narrower and lighter than that of the A-type, bestowing the Prince Henry cars with improved handling and greater pace. The Trial was won by a young, unknown Austrian called Ferdinand Porsche on a 5.7-litre Austro-Daimler, but the Vauxhalls, driven by managing director Percy Kidner, works manager Jock Hancock and German-born director Rudolph Selz, had put up a robust performance, having been timed at no less than 70mph. That August, the three works cars put in an appearance at Brooklands for the O’Gorman Trophy, where they wore more slippery, single-seater racing coachwork. Meanwhile, on 26 October, Hancock took one to a new 20hp speed record at the Surrey circuit, covering the flying half-mile at an impressive 100.08mph.

The Prince Henry Vauxhalls certainly earned their spurs, and the following spring the first customer cars emerged from the Bedfordshire factory, the production version dazzling visitors to the 1911 Olympia Motor Show with its supreme good looks and excellent performance. Based on the chassis of the 20hp A-type – itself a development of the 1908 2000-Mile Trial car – the C10 Prince Henry featured the uprated version of the A11’s five-bearing 3054cc four-cylinder sidevalve engine, and was good for a very healthy 60bhp – a none-too-shabby figure in the context of the day. By way of comparison, the Ford Model T that was introduced in 1908 – and which, with its 2.9-litre sidevalve ‘four’, had a roughly similar mechanical specification – developed a significantly more pedestrian 20bhp. Vauxhall’s Edwardian thoroughbred really was something of a high-performance phenomenon, and the introduction of the 86bhp 3969cc D-type motor in the updated 1913 model elevated its reputation even further – the 4-litre version being good for an astonishing 75mph. Remember, this was a mere 17 years after the Locomotives On Highways Act of 1896 abolished the 4mph speed limit.

When you first set eyes on the Vauxhall Heritage Collection’s beautifully preserved 3-litre Prince Henry (believed to be a pre-production testbed, and in the factory’s possession since 1946, having been first registered in 1910 before moving to Ireland six years later) you can’t help but admire its magnificently rakish lines. The pointed radiator and steeply tapering flanks lend the aesthetics the aura of a period motor launch, while the distinctive flutes that run the length of the bare aluminium bonnet – in a truncated form, they would remain a Vauxhall design cue well into the 1950s – are a wonderfully stylish detail. Tall 27in wheels aside, it’s a remarkably modern shape that looks more vintage than Edwardian, although there’s nothing as newfangled as an electric starter to kick the monobloc ‘four’ into life – a swing on the hand crank being the order of the day.

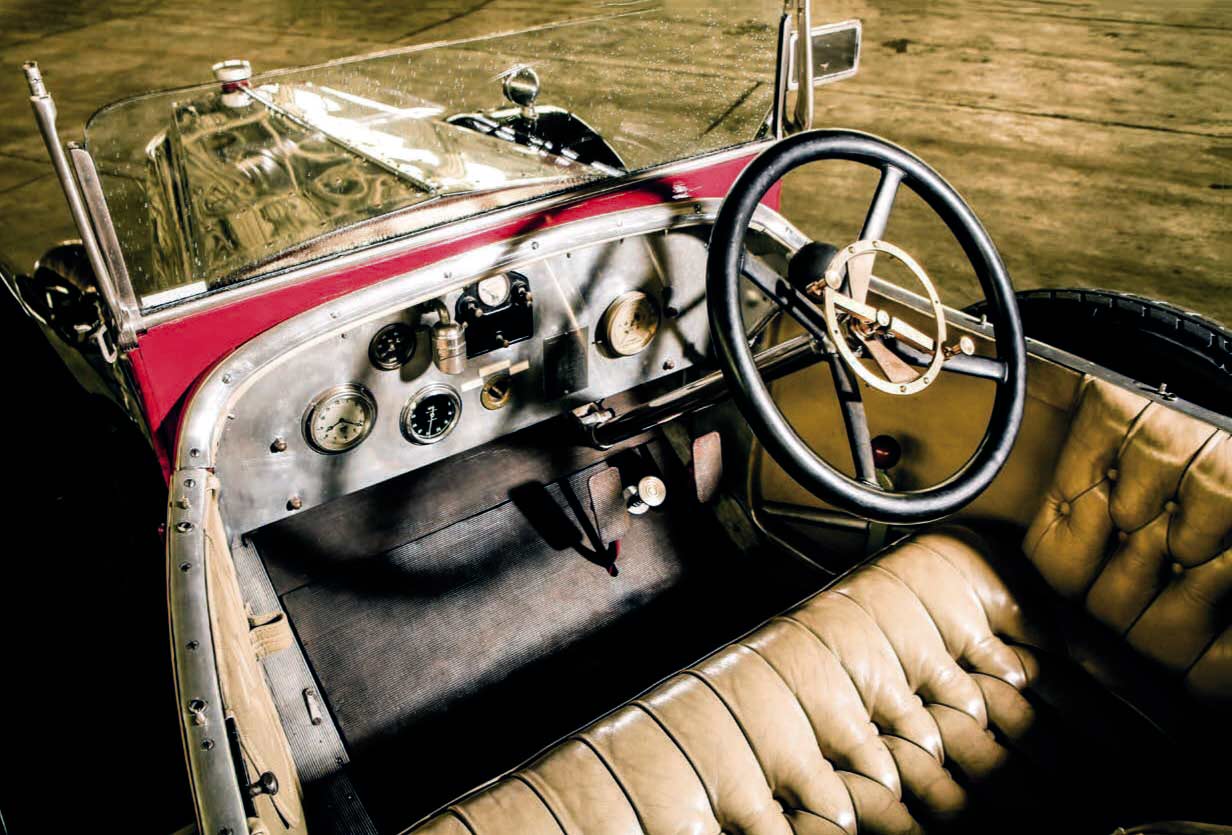

Reach inside the nearside front door for the latch (the side-mounted spare prevents egress from the right) and climb onto the deeply buttoned Chesterfield that serves as accommodation for driver and passenger. The ambience is a wonderful cocktail of Jules Verne and Edwardian high-tech, the polished alloy dashboard panel punctuated by a seemingly random selection of dials with typefaces that seem pure steampunk science fiction. From left to right there’s a clock, oil-pressure gauge, rev counter and ammeter, as well as a gold-faced ‘Stewart Patented Speedometer Mileage Recorder’ that has the appearance of an antique barometer. The fascia boasts little switchgear, but the chunky four-spoke wheel is adorned with a hefty brass ring to which are attached a pair of pleasingly nautical levers: one a hand-throttle and the other for advancing/retarding the ignition. It has the look and feel of a sailor’s sextant, and is a charming centrepiece to this glorious timewarp cockpit. To your right, meanwhile, a large rubber bulb ignites an irresistible and impish urge to parp the horn at each and every opportunity.

The technological progress that took place during the 15-20 years leading up to the Vauxhall’s introduction was remarkable and, unlike the rather unpredictable devices of a decade earlier, the Prince Henry feels like a real car. That said, if you’re unfamiliar with such venerable machinery, the old boy will come across as a rude wake-up call, and you might feel tempted to hang a set of L-plates from its extremities for the first few miles. Expect it to drive like a modern car and this elderly aristocrat will come across all curmudgeonly, so it’s best to take your time and concentrate – beginning with the pedals because, like all the best pre-WW2 designs, this masterpiece of pre-WW1 engineering has a centre throttle. To the left lies the clutch, while to the right is a brake pedal (of sorts), but you can forget about any such mainstream notions as using your leg muscles to arrest the Vauxhall’s progress. As was fairly common practice back in the early days of the automobile, the foot brake acts on the transmission and is best avoided, meaning that two-pedal motoring is the order of the day. If you want to slow down, you’ll need to lean out of the cockpit to haul on the lovely handbrake – it looks as if it’s been purloined from a steam locomotive – that lurks outboard between bodywork and spare wheel.

A stout wooden-topped steel bar by your right shin controls the reverse-gate four-speed gearbox, which places first away from you and forwards with second straight back, while third and fourth are across the gate where you’d normally expect to find the lower two ratios. Slot the lever into first, release the clutch and you are away. The leather-lined plate doesn’t tolerate being slipped, so is very binary in its action, but is pleasant and undemanding – which is fortunate, because it does get a lot of use: the crash ’box requires very deliberate double-declutching as you work your way up through the gears.

As you would expect, piloting the Prince Henry is a refreshingly physical experience: the steering is firm with little discernible selfcentring so negotiating corners means that you have to heave quite deliberately on the thick black rim of the four-spoke wheel before unwinding it all again unless you want to end up on the verge. Riding on such narrow rubber, it’s not especially heavy and it does feel surprisingly direct, but you can’t just let the car steer for you in the way that you would in a modern. But then, of course, you have to remind yourself that this remarkable machine is 108 years old, because before you know it you’ll be speeding along at a surprising rate of knots, accompanied by a deeply rumbustious and highly addictive bellow, while the semi-elliptic leaf springs provide a refined and comfortable ride.

The ease with which the Vauxhall will wind up to 50mph and more is simultaneously a joy and a source of trepidation, because by far the most challenging aspect of the Prince Henry experience is slowing down for obstacles. Approaching bends calls for a considerable mental effort, and planning ahead is very much part of the recipe. The cable-operated rear drums are tiny, and of course front anchors were viewed with the greatest of suspicion by pre-WW1 motorists – to such an extent that the car has none.

As such, Prince Henry neophytes will soon discover that retardation is a juggling act that rapidly tests reflexes and coordination, ideally without the intervention of traffic or errant wildlife and pedestrians. You back off the throttle, pull on the brakes with your right hand, clutch down, let go of the handbrake so you can slot the gearlever into neutral, clutch up, give the big ‘four’ a boot of revs, clutch down, into gear, clutch up, give the brakes another firm tug. It’s a very deliberate process that takes practice, and you’ll need to slow the car considerably more than you think if you want to avoid crunching the cogs, but to get it right is hugely satisfying. Above all, as your confidence in this beguiling machine grows and your pace quickens, it leaves you eager to put some serious miles beneath those skinny Dunlops, so it’s frustrating when the heavens open and the light begins to fade, signalling that our brief encounter is drawing to a close. This Vauxhall is hugely engaging and entertaining, and in its day offered almost unparalleled performance combined with excellent road manners and dashing good looks. It’s easy to understand why wealthy Edwardians clamoured to get behind its wheel – and why it remains so highly regarded more than a century later. This founding father of the sports car dynasty still has what it takes to cause a stir.

TECHNICAL DATA FILE SPECIFICATIONS VAUXHALL PRINCE HENRY

Sold/number built 1911-’1912/58 (including 3 ½ -litre)

Construction steel chassis, aluminium body

Engine cast-iron 3054cc sidevalve ‘four’, single Zenith carburettor

Max power 60bhp @ 2700rpm / DIN

Max torque n/a

Transmission four-speed manual, driving rear wheels

Suspension beam axles, semi-elliptic leaf springs

Steering worm and wheel

Brakes foot-operated transmission brake; mechanically operated 10in rear drums

Wheels and tyres detachable wire wheels with 875 x 105 Dunlop Cord tyres

Length 12ft 8in (3860mm)

Width 5ft 4in (1630mm)

Height 5ft (1524mm)

Wheelbase 9ft 6in (2900mm)

Weight 2352lb (1067kg)

0-60mph c40 secs (estimate)

Top speed 65mph

Mpg 25

Price new £485 (chassis only)

Price now £500,000-plus

‘FORGET ABOUT ANY SUCH MAINSTREAM NOTIONS AS USING YOUR LEG MUSCLES’