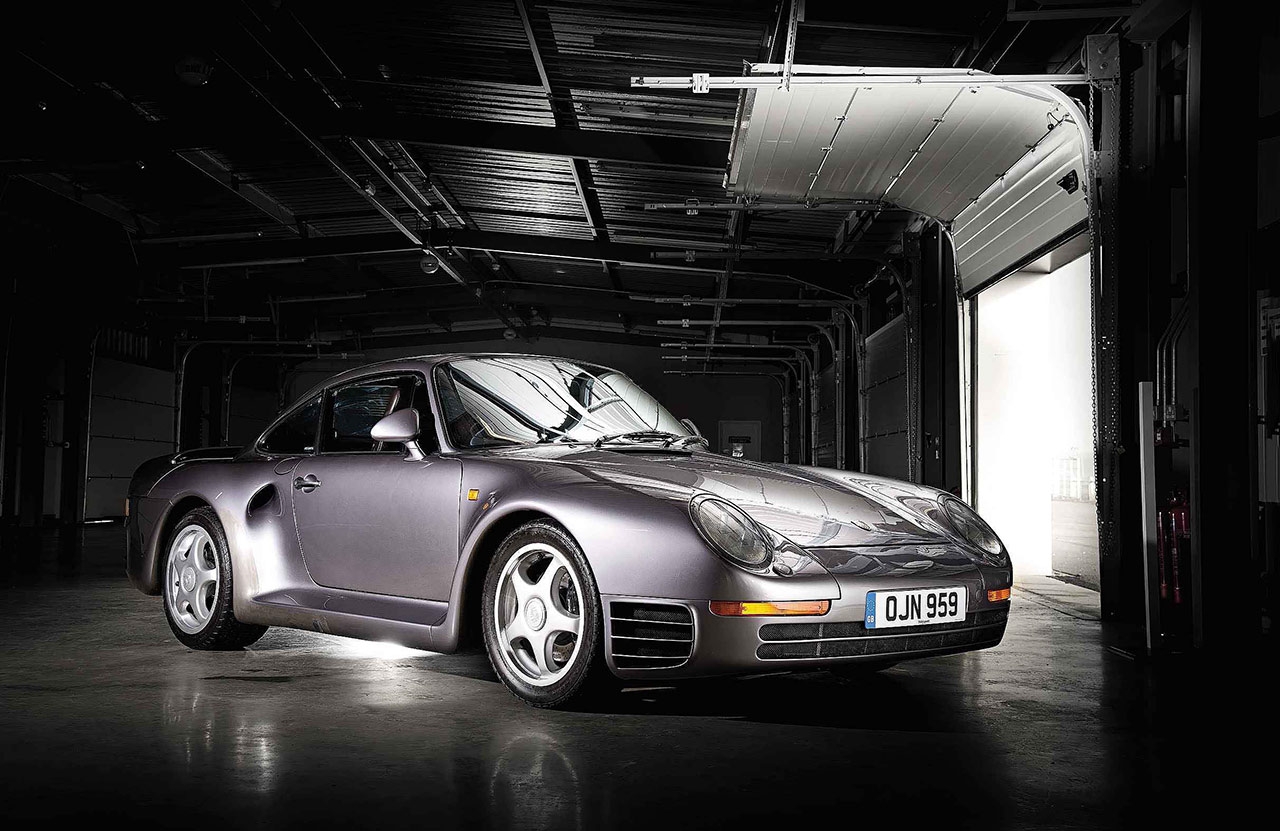

The force was strong. Under the skin of Stuttgart’s game changer. Getting under the skin of Porsche’s techno-fest – and on track with the latest 911 GTS. It’s 30 years since the Porsche 959 landed like the twinturbocharged victor of a war in a galaxy far, far away. Now it’s time for Octane to examine its impact. Words Richard Bremner. Photography Paul Harmer.

It still looks extraordinary, three decades on. The soap-smooth contours, the distended tail and its plank of a high wing, the swollen sills, the massive (by the standards of their day) wheels… the Porsche 959 snares as many eyeballs in the street now as it would have in 1987. But if you do a bit of research and dig out some statistics, the then-to-now comparisons wouldn’t look quite so good. A top speed of 197mph. Today’s £94,316 911 Carrera GTS is only 4mph short. 0-60mph in 3.6sec? The standard 911 Turbo will hit 62mph in 3.0 seconds dead, and crack 198mph. And at £126,925, the Turbo costs a little less in numerical terms – massively so in real terms – than the £145,000 959 did in 1987.

Above. Metallic burgundy leather (with silver seat panels) is something of an acquired taste. What’s more remarkable is the civility and comfort afforded by this monster of a sports car – the antithesis of the lightweight and raucous Ferrari F40. Right. This sub-10,000-mile car belongs to a private collector but was first owned by British Porsche dealer Dick Lovett. Clockwise from above left. It’s based on a 911 so even the 959 features rear seats (and belts); centre console contains switchgear for ride height and damper adjustment; aerodynamic considerations are most evident in the tail; 450bhp Group C-bred powerhouse is in the tail too. Facing page and above. Although the 959 was primarily built as a road car, its development was intended for competition. It scored a one-two on the 1986 Paris-Dakar (above) and even finished seventh overall at Le Mans that same year.

But these comparisons are unfair, of course. You need context, and against the class of 1987, the 959 rides high. Its nearest in-house competition came from the £101,811 911 Turbo Sport, which could manage 171mph and dispense 0-60mph dashes in 5.0 seconds.

The £89,700 Ferrari Testarossa got closer than most with its 180mph top speed, but its 0-60mph sprint time was well adrift at 5.9sec, while Lamborghini’s by-then ageing £86,077 Countach (don’t these supercars seem cheap?) recorded 170mph and 0-60mph in 5.0sec. The 959 rides high, but it doesn’t ride alone.

This was the year of a billionaire’s bonanza, Stuttgart’s shoot for the moon countered by another, equally ambitious missile from Maranello. The Ferrari F40 took a very different road to reach a slightly different set of goals, but what they had in common, apart from fantasy styling for the exhibitionist, was the same capacity for propelling you to another place before you’d barely taken in the first, and for achieving fat multiples of assorted national speed limits.

The Ferrari was all about raw power. Its 478bhp, twin-turbo, 2.9-litre V8 out-muscled the 959’s 450bhp, twin-turbo, 2.85-litre flat-six, and it could outsprint it to 125mph by 0.8 seconds in a spectacular 12.2 seconds. But it did without four-wheel drive, without ABS (amazingly), without the 959’s heightadjustable suspension and without air-con, carpets or even wind-up windows, your yearning for cool air completely unmet by sliding hatches in the Perspex-glazed doors.

The 959 wasn’t created specifically to take on the F40. In fact, it was developed to tackle forest tracks, desert dunes and the future. It was the progeny of engineering chief Dr Helmuth Bott, who was keen to explore the scope for further developing the 911, and Porsche boss Peter Schutz, who was newly installed in 1981 and agreed both to the technical exploration and to the motor sport activities to trial them. The 959 appeared in 1983 at the Frankfurt motor show labelled Gruppe B Studie. That’s about as a dull a term as you can devise for a roadgoing beast featuring the 400bhp engine of a track racer, but not if you knew about the magic of the Group B rally cars storming their way into the memories of WRC fans.

This category of ultimate rally cars allowed their makers creative freedom, provided they built 200 roadgoing versions. Audi produced a 600bhp Quattro on a shortened wheelbase, surgery that rid the car of elegance – yet it was not nearly so ugly as the plastic-adorned MG Metro 6R4, the stunted wedge that was the Lancia Delta S4, or the Cyrano de Bergeracnosed Citroën BX 4TC. That car’s prettier cousin was the Peugeot 205 T16.

Porsche’s mouth-watering Studie was intended for launch in late 1985, and was on offer for what was then an astronomical £133,000, this inflating to £145,000 in the UK. Despite the price, the 200 on offer sold out, some buyers flipping their firm orders to disappointed buyers for as much as £335,000. What either buyer got was a long wait, the first production 959s not emerging until late 1987, despite the roadgoing version appearing at the 1985 Frankfurt show. Such were the challenges of exploring fresh technical terrain on so many fronts. By the time deliveries of roadgoing 959s began, the Group B rally category had been scrapped because it had become too dangerous.

But the car’s potential had already been demonstrated to equally spectacular effect in the Paris-Dakar rally, in those days actually run between these cities rather than in South America. A win here, coupled to years of anticipation of what promised to be the most complex supercar ever made, spared Porsche much of the embarrassment of delivering the finished thing so late. No doubt its colossal appreciation before a single owner had clutched a 959 key also helped.

Despite the familiar roofline and a still more familiar interior, buyers were getting a lot more than a stretched and fattened 911 with fourwheel drive. The quest for strength, low weight, lift-limiting low-drag aerodynamics and the need to envelop much bulkier running gear drove the rather startling metamorphosis of 911 into 959. When 959s were painted white, as they often were, they resembled 911s that had driven deep into snowdrifts.

The swollen lower bodywork was also about that aerodynamic mission. The 911’s drag coefficient of just under 0.4 – not great, even in the early ’80s – was to be smoothed towards an ambitiously low 0.32 target, high-speed lift was to be minimised, and the ferociously powerful twin-turbo engine would demand a lot of chilling air, speedily served. New suspension was needed – we’ll get to that – and a new floorpan to house the all-wheel drive hardware.

All of this, and much else, threatened major weight gain, which is why body panels were to be made from either aluminium or dentresistant Aramid composites. New body panels also provided plenty of scope for reshaping, starting with a nose in polyurethane that was a much more efficient slicer of air than the standard 911 bumper. Part of the resculpting process took place in Porsche’s own wind tunnel, with scale models used ahead of fullsize cars. Although the 959’s roof and glasshouse looked much like a 911’s, its windscreens were flush-mounted, the gutters were sliced off and the door mirrors reshaped.

More unmissable were the alterations to the Porsche’s lower half, its wings smoothly distended to accommodate bigger wheels and a track 2.5in wider than the 911 Turbo’s, while air-vents were let into the forward sections of the rear wings. The unusual running board-like sills linking the front and rear wings would have been the most visually arresting feature of the 959 were it not for the almost ludicrous spread of bodywork overhanging the rear axle, most of it there to provide a pedestal for a rear wing worthy of a light aircraft. But it all worked. The engineers beat their drag target to record 0.31Cd, and the 959 was rare among production cars for generating slight downforce at speed.

The body’s construction would today be described as hybrid, the steel core fitted with doors and front boot lid in aluminium, much of the rest of the exterior moulded from Aramid composite. Only 42 percent of the body was steel, compared with the 72 percent average for European cars in 1985.

The 959’s 450bhp were provided by familiar means, but with a twist. The basis was the 935/76 engine that propelled the dramatic 956 and 962C Le Mans winners, a fine start in the excitement stakes. The bottom end was nearidentical and the heads were not dissimilar, but altered for refinement and maintenance. So rather than six individual cylinder heads being electron-beam-welded to the block – a race-engine precaution to deal with gasketrupturing combustion chamber pressures – the flat-six was capped with a pair of liquid-cooled bolted heads, whose total of four camshafts and 24 valves were chain- rather than gear-driven.

If adapting this race flat-six to run on 95-octane lead-free sounds prosaic, its boosting arrangements certainly weren’t. Twin-turbo engines weren’t new – think Maserati Biturbo – but plumbing them to pump sequentially was more pioneering. The exhaust gases of all six cylinders were funnelled to a first, smaller turbocharger, the second activated by the gases from one row of three cylinders beyond 4000rpm. From 4200rpm on full throttle the two turbos were fed by the bank of three cylinders that each was most closely located to.

A balance pipe evened out the pressures between banks, microprocessor-controlled vacuum valves directing the exhaust gases and the wastegate. The idea was to provide a much broader and more consistent spread of torque with less delay in its delivery – vital characteristics in rallying and the reason for the Group B Lancia Delta S4 employing a supercharger and a turbo.

Despite the sophisticated plumbing, the 959’s 368lb ft torque peak still emerged at 5500rpm, but 295lb ft was available from 2500rpm. More telling was the throttle response, a 2500rpm pedal-flooring in fourth generating peak turbo pressure in 2 seconds rather than the 6.5 needed for parallel turbos. Intriguing evidence of how hard Porsche expected this engine to work is found in the dry-sump lubrication system, which featured one pressure and five scavenge pumps, two of these serving the turbos, and no fewer than seven oil pick-ups to ensure reliable lubrication during high g-force moments.

Those moments were generated by an entirely new four-wheel-drive transmission, new suspension architecture and innovative tyres besides. The permanent all-wheel drive system was novel for being able to vary the torque delivery across the front and rear axles, both automatically and manually, a stalk control allowing the driver to choose between Traction (transmission locked solid), Ice and Snow (40% front, 60% rear), Rain or Dry (both modes again at a basic 40:60 front to rear split, but with more variation), all of this achieved via a multi-plate clutch, a bevy of sensors and some governing microprocessors.

For the multi-plate clutch to function it needed a form of pre-loading, achieved by designing the front wheels to run 1% faster than the rears. That had the potential to cause clutch wear, which is why the maximum torque delivered to the front axle was limited to 40%, and under full acceleration to 20%, reducing wear to the minimum, reckoned Porsche. This early intelligent four-wheel drive system demanded a new suspension layout, Porsche soon discovering that the wheels’ offset from their hubs’ pivot point would need to be minimised if the car wasn’t to perform torquesteering weaves worthy of a big night out. Small offsets are not compatible with strut suspension and wide wheels, which is why coil-sprung double front wishbones were successfully trialled on the 1984 Paris-Dakar cars.

Double wishbones replaced the geometrically destabilising semi-trailing arms at the rear as well, to prevent a shifting rear-wheel toe-in. The 959’s suspension highlight, however, was its octet of dampers. Two per wheel, because each performed a different function, one containing the electric motor enabling the driver to choose between three damper settings, the second doubling as both conventional damper and a means of altering the Porsche’s ride height. An engine-driven pump supplied 120bar of pressure to this end, the car’s height automatically maintained, though without any provision for body-roll control, which was achieved conventionally.

Providing roadgoing tyres for 200mph potential was another technical challenge, because none existed. Porsche was keen to use Dunlop’s Denloc system, which prevents a tyre rolling off its rim – desirable on a car this fast – although Dunlop was beaten to the development of a suitable tyre by Bridgestone. Because both companies were owned by the Sumitomo Bank, allowing Bridgestone to use the patented Denloc system was not an issue, and in time both companies offered 200mph run-flat tyres for the 959.

The wheels themselves were magnesium 17in rims (so small today…) and housed discs clamped by four-piston calipers overseen by a Wabco anti-locking system. It featured sensors on all four wheels – not a given, back then – and required careful development to ensure compatibility with all-wheel drive. The runflats allowed the spare wheel to be ditched, which was very good news for the engineers who had to accommodate a differential, a clutch, driveshafts, a twin-fan radiator, an airconditioning condenser and a larger 90-litre fuel tank in the front end of what had started out as a 911. Not surprisingly, the 959’s luggage capacity shrank somewhat.

Porsche made a loss, and a substantial one at that, on every one of the 292 roadgoing 959s it sold. But that isn’t the way to look at this project, as Schutz and Bott no doubt told the company accountants. Their vision illuminated the 911’s engineering future for the next 30 years and beyond, a substantial achievement. And it wasn’t only the 911: Porsche’s embrace of four-wheel drive led it towards the Cayenne and Macan, models that underpin the company’s financial health, even if knowledge of them would have shocked Porsche customers in 1985.

The 959 also demonstrated what was dynamically possible. Corralling 450bhp and 368lb ft of torque and effectively transmitting it to tarmac lay at the outer edges of the possible, for road cars at least, back in 1987. What came next was Porsche’s step-by-step advancement towards providing 959 performance in mainstream models pitched at more affordable prices. Back in 1987, the 911 was still a tricky car to handle on the limit (lift and you might spin), or going down wet hills (limited frontend grip), or entering very tight turns too fast (terminal understeer) and, though much faster, the 959 was vastly more able.

First up was the 964-generation 911 Carrera 4, which appeared just a year later in 1988. Four-wheel-drive 911s have since been a given, as has a perpetual rise in power, grip and braking potential. Curiously, however, it was not until 1995 and the emergence of the 993-generation 911 Turbo that permanent four-wheel drive was combined with forced induction again, this arrangement persisting with every 911 Turbo since. This model easily out-accelerates the 959 today, but owes much of its development to a 1980s technical torchbearer that has become a legend.

While Porsche made a loss on each 959 it sold, you could have made yourself a whole lot better off – rich even – by buying one. The first opportunity came 34 years ago, when Porsche showed the 959 concept at the 1983 Frankfurt show. If you’d ordered one then at around £133,000, you’d have been able to more than double your money over the next four to five years, while Porsche battled it into production.

Prices fell away in subsequent years, the market supplied with an increasingly wide array of ever-more-able supercars, and a 911 range whose abilities progressively closed in on those of the 959, just as Porsche had intended. Investing a spare £200,000 in a 959 would have been a shrewd move back then.

But 959 values have gradually gathered momentum over the past decade, and enjoyed a huge boost triggered when it became a quarter-of-a-century old. Why? Because it was at this point that cars could be imported into the USA without having to comply with the federal regulations that applied when they new. That’s significant for the 959 because this car was never officially sold in the US, although Bruce Canepa’s engineering operation modified a few to comply.

As 2014 approached, notes HAGI Index founder Dietrich Hatlapa, ‘this really made a difference. From a bit before 2014, prices jumped from just under £500,000 to significantly above that’. Hatlapa points out that ‘there are big differences in price between the various models’.

The bulk of the 292-strong production run are the well-equipped Komfort version – ‘an unfortunate name’, Hatlapa reckons, because it seriously under-describes the car’s potential – with only 29 of the total accounted for by the much rarer 515bhp Sport. The best Sports are worth almost $1.5m, as are any of the eight 959s Porsche built from spare parts in 1992/93. The more common (but still rare) Komfort will cost $1m to $1.1m, reckons Hatlapa. ‘Most are low-mileage,’ he says, ‘but service history is a big issue. If they are not serviced it can cost 100,000 in any currency to recommission one.’

Besides the 292 plus eight, there are also 30-odd prototypes (Porsche made 37 in all) that are generally worth less than the finished thing, not least because some are not that close to the final specification.

And that specification is really what this car is about, after all…

‘The 959 illuminated the 911’s engineering future for the next 30 years and beyond’