Tour De Force Quattro Power! How Audi’s technological masterpiece changed the world. Four-wheel drive, turbocharged – and room for the family. The amazing quattro Jörg Bensinger and Michèle Mouton remember the great all-rounder. The turbocharged, four-wheel-drive quattro changed the face of performance motoring. James Page tells the story of Audi’s fast, practical and charismatic all-rounder. Photography Tony Baker/LAT.

Given Audi’s current status as a global powerhouse, supercar manufacturer and 13-times Le Mans winner, it’s astonishing to recall the impact of the original quattro and the fact that it represented a quantum leap for the marque. Thirty-six years ago, people did not expect to buy their cutting-edge performance cars from Ingolstadt, but its four-wheel-drive masterpiece changed all that – ably assisted by a revolutionary rally programme and, in the UK especially, the inspired ‘Vorsprung durch Technik’ advertising campaign.

By the time the ‘Ur’ quattro ceased production in 1991, the perception of Audi among the general public was very different to 11 years previously, and it’s difficult to overemphasise the quattro’s part in that. The man who kickstarted the concept was Jörg Bensinger, who had joined Audi’s R&D section in 1968. With a wealth of chassis and transmission experience behind him by the mid-1970s, he was passionate about applying four-wheel drive to a performance car, arguing, for a start, that the technology would make such models easier to control at high speeds.

“I was convinced about four-wheel drive,” he remembers today. “I began my career at Porsche, where I was working with rear-wheel drive and rear-engined cars. Then, when I moved on to BMW and Mercedes-Benz, it was rear-wheel drive and front-engined. At Audi, it was front-wheel drive and front-engined. The only thing missing was four-wheel drive!”

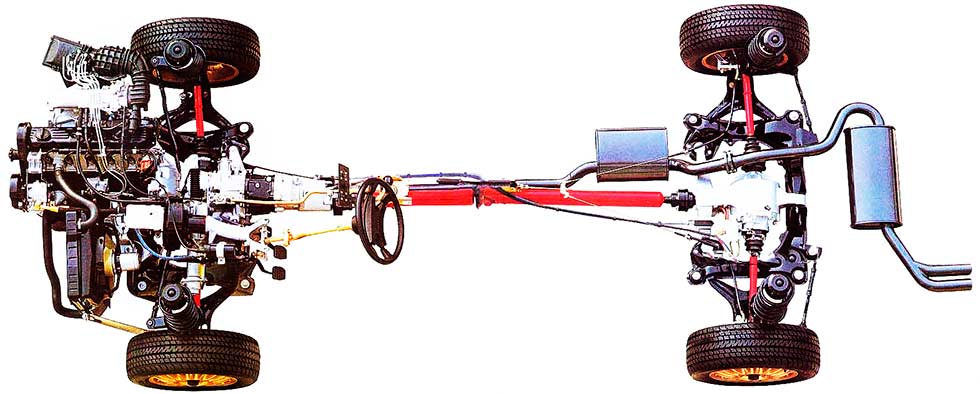

Audi Quattro transmission

For a long time, however, his ideas existed only on paper, with no practical way of making them a reality. But then Audi became involved with the development of the Volkswagen Iltis, a small new military vehicle that would boast four-wheel drive. During winter testing in Scandinavia, the Iltis – fitted with a humble 1.7-litre ‘four’ – romped away from much more powerful two-wheel-drive Audis, and Bensinger recognised his opportunity.

“I knew that, theoretically, it should have been possible,” he explains. “Then the Iltis came along, so we built a car with which to convince the Volkswagen establishment. I didn’t have much support at the start – really, the only help came from Ferdinand Piëch. Most of the others were against it! In fact, Volkswagen wanted to convince Audi not to do it.”

Piëch had enjoyed a stellar career at Porsche – overseeing, among many other things, the 917 racing programme – before joining Audi in 1972. By the time of the quattro project, he was on the board at Ingolstadt and in charge of technical development. He proved to be a key supporter.

In March 1977, Bensinger took an Audi 80 and fitted it with the Iltis transmission as well as the 160bhp five-cylinder engine from a 200 Turbo. Along with Walter Treser and Hans Nedvidek, he set about proving his concept. In January 1978, they took the prototype ‘A1’ to the steep, daunting and snow-covered Turracher Höhe pass in the Alps, and invited Volkswagen’s most senior sales and marketing folk along. Despite not wearing winter tyres or chains, the car made its way up a road that at the time, so legend has it, normal traffic couldn’t even get within 2km of, let alone drive up.

Volkswagen’s sales director was Dr Werner P Schmidt, and even after the demonstration he wondered who would buy the 400 examples that needed to be built for motorsport homologation. Bensinger: “I replied to him that, if he gave me a licence, I’d sell them myself.”

That involvement in motorsport would take the form of rallying, even though competition was emphatically not the quattro’s raison d’être. “It was always in my mind that it would just be a road car,” confirms Bensinger. “But, at that point, Audi was not in the position – like, for example, BMW and Mercedes were – to introduce something like this without promotion and publicity behind it. It was a very, very important car for the company. Along with the development of the direct-injection diesel, it got Audi to where it is now.”

For it to work as a road car, though, the concept had to be proven on hard, dry surfaces as well as loose, slippery ones. Audi therefore took the 160bhp prototype to Hockenheim, where it lapped the circuit’s ‘short’ layout only slightly slower than a Porsche 928 that had been brought along for comparison.

The potential was clearly there, but engineers had identified areas for improvement. Having driven the car, Paul Frère confirmed the need for a centre diff to improve its low-speed manners. As he later wrote in Road & Track: ‘I found that scrub due to the lack of an intermediate differential was noticeable only on sharp corners – rather annoying when driving around town’.

The answer was to fit a modified version of the differential from the VW Polo/Audi 50, but the really clever bit was to transmit power to it from the gearbox via a hollow output shaft. A pinion shaft turning within that then took drive forwards again to the front wheels.

Even after production approval had been given, Bensinger was leading a team containing fewer than a dozen engineers, but still they managed to get the car ready for a stunning debut at the 1980 Geneva Salon. Earlier this year, C&SC asked the vastly experienced motoring writer Mel Nichols for his favourite memory from the Swiss showpiece, and he instantly plumped for the quattro’s first outing. ‘On the wet, icy and snowy Swiss roads it was a revelation,’ he wrote. ‘Most who drove it that day loved it and hailed it as a revolution.’

When Gordon Wilkins from Autocar magazine got his hands on one, he agreed with Nichols: ‘I felt like a visitor from another planet for whom the laws of nature have been suspended.’ Despite the fact that, at launch, the quattro cost twice as much as the firm’s next most expensive model (the 100, which sold for DM25,000), it was obvious to everyone that Audi was going to be able to shift far, far more than the original prediction of 400. Soon, 3500 became the target, but in the end more than three times that number would leave the factory.

From launch until 1982, the car was available only in left-hand drive, but during that time David Sutton Motorsport and GTi Engineering would carry out conversions for UK customers. For the ’83 model year, the quad-lamp nose was replaced by the single rectangular Cibié headlights and left-hookers received a new digital dashboard that made it to the UK for ’1984. That was also the year in which ABS was introduced, as were wider wheels – 8in, up from 6in – and a ride height that was 20mm lower all round.

For 1988 came a slightly larger 2226cc engine with a smaller turbocharger, plus a Torsen centre diff, which Bensinger confirms is the unit with which the quattro would have been launched in an ideal world. Rather than splitting drive 50:50 between front and rear, it could send anywhere between 25% and 75% of power to the axle that had the most grip.

And finally, in 1989 the 20-valve version was introduced. Its crossflow cylinder head with four valves per cylinder and twin camshafts was derived from that seen in the short-wheelbase, 306bhp, homologation-special Sport quattro of 1984. With 220bhp and, more importantly, 228lb ft of torque spread over a wider rev range, it saw the quattro through to retirement in 1991.

Our featured example is owned by Tristram Belemore-Smith, who is only the car’s second keeper. It was bought from Whitehouse Audi on 20 June 1986 by a Mr Palmer. He also purchased a Volkswagen Scirocco for his wife at much the same time – she still owns it. For many years, Palmer would drive the car from Norwich to London to get it serviced at a main dealer, but it was put into storage in 2009 when he fell ill.

Belemore-Smith bought it early in 2016, and recommissioned it “with little effort”. He reports that it’s pretty easy to work on, but he’s used to fettling cars – he currently owns a Mini Clubman estate, a Saab 900 Turbo, a Fiat Uno and “a few” classic ’bikes. Apart from very minor paintwork that was required to return it to A1 condition, it’s a remarkably original survivor.

To keep costs under control, the distinctive boxy shape was based upon the Audi Coupé – itself a development of the 80 platform – and styled by Brit Martin Smith, who was only 30 at the time. Even at rest, it’s full of presence thanks to its flared wheelarches and aggressive stance.

Inside, it’s very black. The digital display helps a little: in front of you are readouts for revs, speed, water temperature, fuel level and oil pressure – a small bar slides right and left as it fluctuates, which brings to mind Pong. On the centre console are the controls for the electric windows and the diff lock, plus digital gauges for the battery and oil temperature that look as if they’re part of a period graphic equaliser.

And there’s more 1980s ‘high tech’ to enjoy if, for example, you leave the lights on. Rather than the gentle, almost apologetic ‘bong, bong’ that you get from a modern car, the Audi sounds a sharp, single-note alarm before a stern female voice informs you of your mistake. When presented with this feature, I’ve always found it impossible not to recall Chris Goffey’s story of rolling a Maestro while testing it for Top Gear. As he sat there, upside-down, the digital voice said: “Oil pressure low.”

The Audi’s driving position is good, though, with the controls for lights and suchlike arranged a fingertip’s stretch away on the main instrument binnacle – a little like the brilliant arrangement on some Citroëns, but with a rather more solid feel. The rear seats are generous for a coupé, and the only real drawback to this particular cabin is that, on a summer’s day, it gets incredibly hot.

The basic quality of Bensinger’s concept soon makes itself clear because a quattro is still a very easy car to drive quickly – and even today it really does feel fast. It doesn’t do a great deal below 3000rpm, but push beyond that and it comes alive, the thrum from the five-cylinder engine being accompanied by a strangely addictive ‘chirrup’ as you lift off to change gear – a slightly unsatisfactory process thanks to the shift somehow being both spongy and a little notchy.

Once it’s on boost and under way, the quattro delivers a sustained and effortless shove in the back, and maintaining that momentum is almost embarrassingly straightforward. Through long, fast corners, the Audi is supremely composed, with the nicely weighted steering enabling you to place it accurately. In tighter bends it exhibits a surprising amount of body roll – the payoff being a ride that is very much on the comfortable side of firm – but it grips tenaciously, and you can get on the power earlier and more confidently than you would in a rear-drive car.

Overdo it, and you’re far more likely to leave the road forwards than backwards. The reason becomes clear as soon as you open the bonnet and notice that the engine, in its entirety, is mounted ahead of the front axle line. It’s so far forward that the radiator is to one side and behind it, while changing the cambelt is made more complicated by the fact that it’s almost up against the slam panel.

But while that layout may have caused on-the-limit handling issues for the Michèle Moutons of this world, it’s not something that you’ll notice while motoring at anything below what Denis Jenkinson referred to as ‘ten-tenths’. Few cars flatter you as much as this, or enable you to so easily tap into their reserves of performance. On the right sort of road, I dread to think how much you’d need to spend to buy something genuinely capable of leaving it for dead.

Bensinger and his team succeeded because, far from being heavy, complicated and expensive, their ingenious four-wheel-drive system was based almost entirely around existing components – such as the 80’s front suspension.

Complete with subframe, this was turned around to form the quattro’s rear set-up. The fact that Audi used longitudinal front-drive powerplants also helped, as did the resources that came with being part of the VAG family.

And yet they still had to make the most of the opportunity that presented itself. Amazingly, the final powertrain was only 165lb heavier than its front-drive equivalent, and only 77lb more than a rear-drive set-up would have been.

“Our system was easy to realise and to put into production, and if I was to do it again I wouldn’t change it,” concludes Bensinger. “I was able to do things exactly how I wanted. Even though I was convinced it would work, I could never have imagined that, today, 45% of all Audis sold would have the quattro driveline.”

None of its individual features were, of themselves, revolutionary. It was far from being the first car to boast turbocharging or four-wheel-drive, for example, but it combined everything in a hugely desirable package that gained recognition and acceptance not just from cognoscenti, but from the wider public. It’s quite a legacy, and one for which everyone in Ingolstadt owes Piëch, Bensinger and his fellow engineers a debt of gratitude.

From top: digital dash is very 1980s; KKK turbo; 1981 Motor test in ideal quattro conditions; rapid pace can be maintained on small country roads.

The Audi’s straight-line performance is still impressive by today’s standards. Above: the standard 215/50 15 tyres can be difficult to find.

Specialist view

Adam Marsden has been into quattros since his dad’s boss threw him the keys to his then-new 1981 example and invited him to take it up the road. His company AM Cars (01460 55001; www.amcarsquattro.co.uk) services, restores and sells quattros, as well as preparing them for rallying and sending parts all over the world.

“For a car that’s solid, MoT’d and ready to use, you’re now looking at a starting price of £15,000,” he says. “Anything less than that is likely to need recommissioning, and you need to watch for corrosion on the sills, wings and pillars. The early and late cars can make bonkers money, but generally it depends more on a car’s condition than its year. We’ve got a 1987 example with only 30,000 miles on the clock and that’ll be £40,000-plus.

“People often mention the fact that some parts are hard to come by, but they’re there if you look. Various companies, including us, have had bits remade and you can still locate secondhand parts, too. Audi Tradition has the odd new door and bonnet, but the rear panel is currently a bit of a struggle to find.

“They’ve always had a good following, but that’s really picked up in the past 24 months. Before that, the TV series Ashes to Ashes helped, too. Considering that they only made about 11,500 of them, it’s amazing how many are still around. We see a lot that have been in long-term storage, and a lot depends on where they’ve been kept. We had one recently that had come from Jersey and the sea-salt had got to it. “Unless a car’s really been looked after, be careful – and get it inspected first!”

‘IT’S FULL OF PRESENCE THANKS TO ITS FLARED WHEELARCHES AND AGGRESSIVE STANCE’

Ultimate hillclimb Quattro

Anyone who followed British hillclimbing in the 1980s and ’90s can’t fail to recall the sight and sound of Tom Hammonds’ cars, which – in an inspired touch – he often used to tow with his Sport quattro.

“Tom was an enthusiastic motorist,” recalls his brother Geoffrey.

“Perhaps that came from our mother, who liked anything on four wheels so long as it was fast, and drove her drophead BMW into her 90s.” Tom’s first competition quattro was sourced from specialist David Sutton. “He also visited the factory on several occasions,” adds Geoffrey. “Some bits they would sell to him; with others, he was told to put his chequebook away!”

That ex-Mikkola car, with “only” 580bhp, was later replaced by a 1986 E2. “[Tom’s son] Mark thinks this might also have been via Sutton,” says Geoff, “but I recall Tom telling me that it came direct from the factory and that they were rather unwilling to part with it. He could be very persuasive.”

Tom turned it into a replica of the be-winged Pikes Peak quattro. “Mark recalls him making the moulds in his workshop,” explains Geoff. “He was a very inventive engineer, using an old shunting engine that he rebuilt to generate electricity – and using the cooling water to heat his house.”

The engine was rebuilt by Lehmann to give about 720bhp, but Geoff recalls the aerodynamics being somewhat troublesome: “He visited MIRA, a couple of miles down the road from his base in Hinckley – and literally over the fields from where we were brought up – to undertake development in their wind tunnel.”

With the quattro fully sorted, Hammonds posted a closed-car record at Shelsley Walsh (28.58 secs) that stood for more than 10 years. When Tom died in 2002, the car went into Sutton’s motorsport museum, only to be sold when that shut down.

The familiar five-cylinder engine is mounted well forward. This one is a 10-valve example; later 20-valve cars featured a twin-cam cylinder head.

Hammonds in the second of his hillclimb quattros, which he turned into a fearsome Pikes Peak replica. Here, he attacks Prescott in 1990.

Michèle Mouton: changing the face of rallying

“As soon as I drove the quattro, I knew that it was the future. It was so efficient. Four-wheel drive made such a big difference – we had to get used to the rear not sliding, for a start. It was a bit difficult at the beginning, but I soon understood from Hannu [Mikkola] that left-foot braking was the way to go. It allowed you to play with the car a bit and also keep the revs up because there was a lot of turbo lag. You learn quickly, then you forget about all the cars you’d driven before!

“I liked the quattro very much. It gave you so much confidence and was nice to drive. When I won in San Remo in ’1981, any problems were only mental ones with me – not with the car. There were narrow, tricky stages at the end and I was fighting with Ari [Vatanen]. I said to [co-driver] Fabrizia Pons that I was going to treat the final stage as if it was the first one, not the last. That took the pressure off me and I was able to win. When you win for the first time, you know that you can do it, so you’re more comfortable.

“In 1982, I missed the title by very little and that was my best year. We had everyone at Audi behind us and we were really working well as a team. Hannu was fantastic. I had no experience in setting up the car, but we trusted each other completely and would share details. I say to girls now that it was important for me to seize the opportunity because I had exactly the same car as Hannu. And it was the best car, too. I had to reach his level and not look ridiculous.

“The short-wheelbase quattro was my favourite. It was so powerful! All of them were at their best on gravel, though. They’d always be talking to you, telling you how much grip there was. There was no comparison between that and how it was on asphalt. The Monte was hard because sometimes you’d have snow, sometimes not. And sometimes there would be ice. In Sweden, on proper snow, it felt as if you were dancing.

“When we went to Pikes Peak, we had a car with a bit more power and there were difficulties due to the altitude – as well as the fact that we were European and I was a woman! It’s true that, when Bobby Unser said a few things, I told him that, if he had the balls, I’d race him back down the mountain.

“When I drove the Peugeot 205T16 in 1986, it felt like a toy after the Audi. It was not such a monster – it was very compact, but quite nervous. In a way, it was more fun because the engine was in the back but you cannot compare the two. They’re like dresses – you can have very different dresses but love them both!”

“It’s amazing that people are still talking about those days more than 30 years later.”

“It was important for me to seize the opportunity because I had the same car as Hannu – and it was the best car, too”

Interior is beautifully made but unremittingly black, with the exception of the small doorhandles. Above: rear seats are comfy for smaller adults.

Mouton and Pons on their way to victory in Portugal, 1982 – the year in which the Frenchwoman finished runner-up in the title race.

TECHNICAL DATA AUDI QUATTRO

Sold/number built 1980-’1991/11,452 (all)

Construction steel monocoque

Engine iron-block, alloy-head, single-overhead-camshaft 2144cc inline-five, KKK turbocharger, Bosch K-Jetronic fuel injection

Max power 200bhp @ 5500rpm

Max torque 210lb ft @ 3500rpm

Transmission five-speed manual, driving all four wheels

Suspension independent by MacPherson struts, lower wishbones, anti-roll bar f/r (front only from 1983)

Steering power-assisted rack and pinion

Brakes discs, ventilated at front

Length 14ft 5 ½ in (4404mm)

Width 5ft 8in (1723mm)

Height 4ft 5in (1344mm)

Wheelbase 8ft 3 ½ in (2524mm)

Weight 2844lb (1290kg)

0-60mph 7.3 secs

Top speed 135mph

Mpg 19

Price new £24,204 (1986)

Price now from £15,000

Quattro bodyshell was a beefed-up take on the Coupé. Above: cutaway shows centre differential and two-piece propshaft taking drive to the rear.

{module Audi Quattro 156}