Hex Appeal. Driving Lamborghinis sensational Marzal. One of the greatest-ever show cars has hardly been seen in public. Drive-My scores an exclusive drive in the Lamborghini Marzal. Words Massimo Delbò. Photography Max Serra.

Lamborghini Marzal. Driven for the first time in 50 years. The Marzal looks like a spaceship, made mostly from glass, with four seats and a rear-mounted engine’

Monaco, Sunday 7 May, 1967. It’s early afternoon and the sun is high, with just a few minutes to go before the start of the Formula 1 Grand Prix. His Serene Highness Prince Rainier III slides into the driving seat, ready for his traditional pre-race lap. To his right sits his wife, Princess Grace, and photos of the two, inside the car, will be seen all over the world next day. Ferruccio Lamborghini is a happy man: this is pure marketing gold for his company, Automobili Lamborghini, barely four years old but already successful.

The Lamborghini-badged car on the racetrack is the latest creation of young designer Marcello Gandini, for Carrozzeria Bertone – and it is about to become one of the most renowned show-cars ever built. It’s called the Marzal, taking its name from a fighting bull like the Miura did a year before it, and it looks like a spaceship, seemingly made mostly from glass, with four seats and a rear-mounted two-litre, six-cylinder engine.

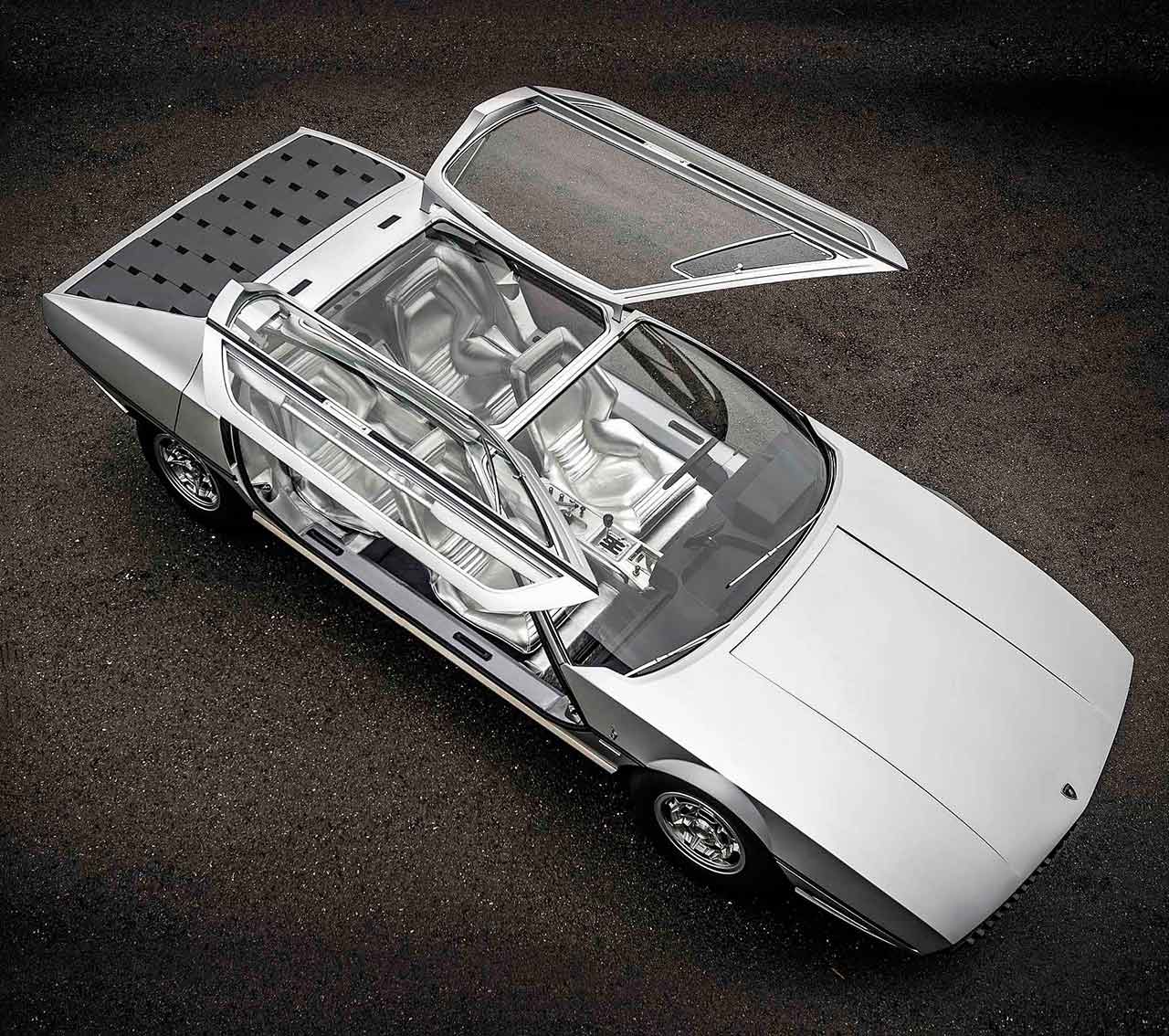

The Marzal created a stir when it was shown for the first time the previous March, on the Bertone stand at the Salon Auto Genève. People reacted with disbelief the moment they saw the Marzal’s unusual surfacing: 4.5 square metres of glass, made by the Belgian company Glaverbel, which transformed the cockpit – and its huge ‘gullwing’ doors – into a transparent bubble.

‘For us, the success at the show was a great relief,’ Marcello Gandini tells Drive-My. ‘A show car is successful if onlookers are amazed by it, their mouths wide open in surprise. I was worried because, after months of working day and night, just a few hours before it was shipped to Geneva I saw the guy in charge of sweeping the floors at Bertone approaching it. I’ll never forget him, leaning on his broom with a cigarette in his mouth, slowly looking over the car, shaking his head disapprovingly.’

The design of the Marzal dates back to the summer of 1966 when Gandini, fresh from his success with the Miura, began to dream up a show car for the following year. Delivering a stunner for Geneva was a tradition for Bertone, and Gandini wanted to imagine something completely different from contemporary sports cars. ‘The beauty of a show car is the unlimited freedom it allows its designer,’ says Gandini. ‘You don’t need inspiration: you just do it, without having to follow too many rules. I wanted to create a four-seater with a lot of glass and gullwing doors – the perfect opening for a four-seater. I made some draft drawings and called Sant’Agata to ask for the technical help of my friend, the late engineer Paolo Stanzani.’

What Gandini wanted was a new engine, small enough to be positioned transversely at the rear. So he proposed a 2.0-litre straight-six, in essence half of Lamborghini’s 4.0-litre V12. ‘We were involved from the very beginning of the Marzal project because we had to supply the powertrain,’ remembers Gian Paolo Dallara, former technical director at Lamborghini, and leader of the engineering team that created the Miura. ‘We were fresh from the success of the Miura, and still young. Stanzani and myself, together with Gandini for Bertone, could do something really daring. We had to cut the V12 to create space for the two seats on the back; there was no way we could have had the V12 in that space, as the Marzal is only 6cm longer than the Miura. We asked the company in Bologna, which cast the blocks for the Miura, to modify one of them to make a six-cylinder.’

That engine remains, to this day, the only six-cylinder ever manufactured in Sant’Agata. It’s cast integrally with the gearbox, and had to be fitted in such a way that the gear linkage works in reverse format, with first gear down to the right, away from the left-hand-drive steering wheel.

Of course, one of the Marzal’s most amazing features is the gullwing doors, which run the full length of the cockpit, allowing four people to get in at the same time. Because of their size and the quantity of glass they contain, they needed a lot of engineering work to make them function.

‘The opening of the doors was one of the main issues we had to solve in the Marzal,’ says Gandini. ‘There weren’t any compensators available that could safely keep the doors open, so we had to create our own system. We used modified steering racks, with springs and pulleys actuated by steel cables. They were huge, heavy and difficult to set properly, but they proved to be very reliable. Another potential difficulty was the lack of safety in case of the car rolling over, but as the Marzal was a one-off we didn’t have to think too much about it.’

After the Geneva Show, the car went to Sant’Agata Bolognese for evaluation. It is based on a lengthened Miura structure, the frame having been supplied to Bertone from Marchesi, the manufacturer of the Lamborghini chassis. Its build number – Type P200 Marzal chassis 10001 – is not registered in the Lamborghini archive, and there were important modifications at both ends, especially at the rear, where the front section of a Miura chassis was fitted in reverse. Even though Gandini is adamant that the Marzal was a show car only, and never intended for production, it is fair to say that Lamborghini’s engineers at least thought about it. Ferruccio Lamborghini himself was certainly thinking of developing the range with something cheaper than the Miura and with four seats. Eventually, of course, the V8-powered two-seat Urraco arrived – but the four-seat Espada V12 was first built in 1968.

‘To me the Marzal is one of the most beautiful cars of its era,’ says Gian Paolo Dallara. ‘The 2+2 concept car was very tempting but we soon decided that it would never be put into production. I remember when I drove it for a few kilometres, at low speed, just to get the feeling of the car. It was very long and its weight distribution and mechanical tuning were still very immature; Bob Wallace had only limited opportunity to develop it. The truth is that, in 1967, Lamborghini was a young and small company, and every effort was channelled towards Miura development and its production, leaving very little space for other developments such as a new, revolutionary 2+2.

‘The beauty of a show car is the unlimited freedom it allows. You don’t need inspiration: you just do it’ Marcello Gandini’

‘The main reason was the engine. A 2.0-litre wouldn’t have provided the power expected of a Lamborghini; the figure was about 175bhp. That would leave our customers well short of Modena’s competitors, and the costs of its development were prohibitive. We speculated that potential customers would never agree to pay as much for a six-cylinder car as for a 12-cylinder. And that is why we decided not to go any further.’

Even so, the car was shipped to Monaco for the Formula 1 weekend. The previous year the Miura had stolen the show in Monte Carlo, and Ferruccio enjoyed the results of this sort of publicity. ‘The Miura was driven to Monte Carlo,’ recalls Dallara, ‘but the Marzal was shipped. It would have been impossible for it to complete the journey on the road. The main target was to have it parked in front of the Grand Hotel de Paris. How Ferruccio, a man with great spirit and vision but without international connections, ended up with the Prince driving it before the Grand Prix, even risking the car breaking down in doing so, is still a mystery to me.’

There are no official documents to prove it, but renowned Lamborghini historian Stefano Pasini believes that the man behind the Marzal’s Monte Carlo lap was Etienne Cornuille, a French aristocrat involved with Lamborghini since the company’s early days as a car maker.

After Monaco, the car was taken back to Lamborghini for further testing before it was returned to Bertone. ‘We needed to refill it and I was curious to drive it, so I drove the Marzal to a small gas station in a village close to Turin,’ recalls Gandini. ‘What was most amusing was seeing the expression on the face of the gas station attendant.’

‘The Marzal feels like a noisy soap bubble, jostling along just a few inches above the tarmac’

In October 1967 the Marzal was shown on the Bertone stand at the Earls Court Motor Show in London, but by the following January its time was up. It went on official display for the final time at the Auto Salon à L’Etranger exhibition in Brussels, Belgium. The car was supposed to be shipped to America soon afterwards, for a promotional tour, and was transported to Genoa to be loaded onto a ship. However, some paperwork was missing and there was a problem with a tax payment, so the Marzal was impounded by the customs department and spent more than a year outside, by the docks.

Wet weather and salty Mediterranean air took their toll and, when it met its maker again, the Marzal was no longer the fresh-faced show car it had been. It was parked in a warehouse, where it remained for a few years before Bertone decided to prepare it for display in the company museum, after minor repairs, new paint, and a steering wheel and gearknob of new design. And there the Marzal’s story came to a halt.

Until 2011. The Marzal was offered for sale with other prototypes at the RM Auctions sale in Villa Erba, Como, following the bankruptcy of Carrozzeria Bertone, in a bid by the court to raise enough money to pay the employees. It was bought by a European collector, and found not to be in very good shape: five years of hard work were required to return it to its original show-stopping magnificence. All the lower body was badly rusted, and it soon became clear that the cockpit had suffered from water ingress during that year by the docks in Genoa: the leather trim was badly perished. As for the unique mechanicals, the last service was likely more than 30 years ago. That unique straight-six was fully overhauled; at least its components (bar the cylinder block) are shared with other Lamborghinis.

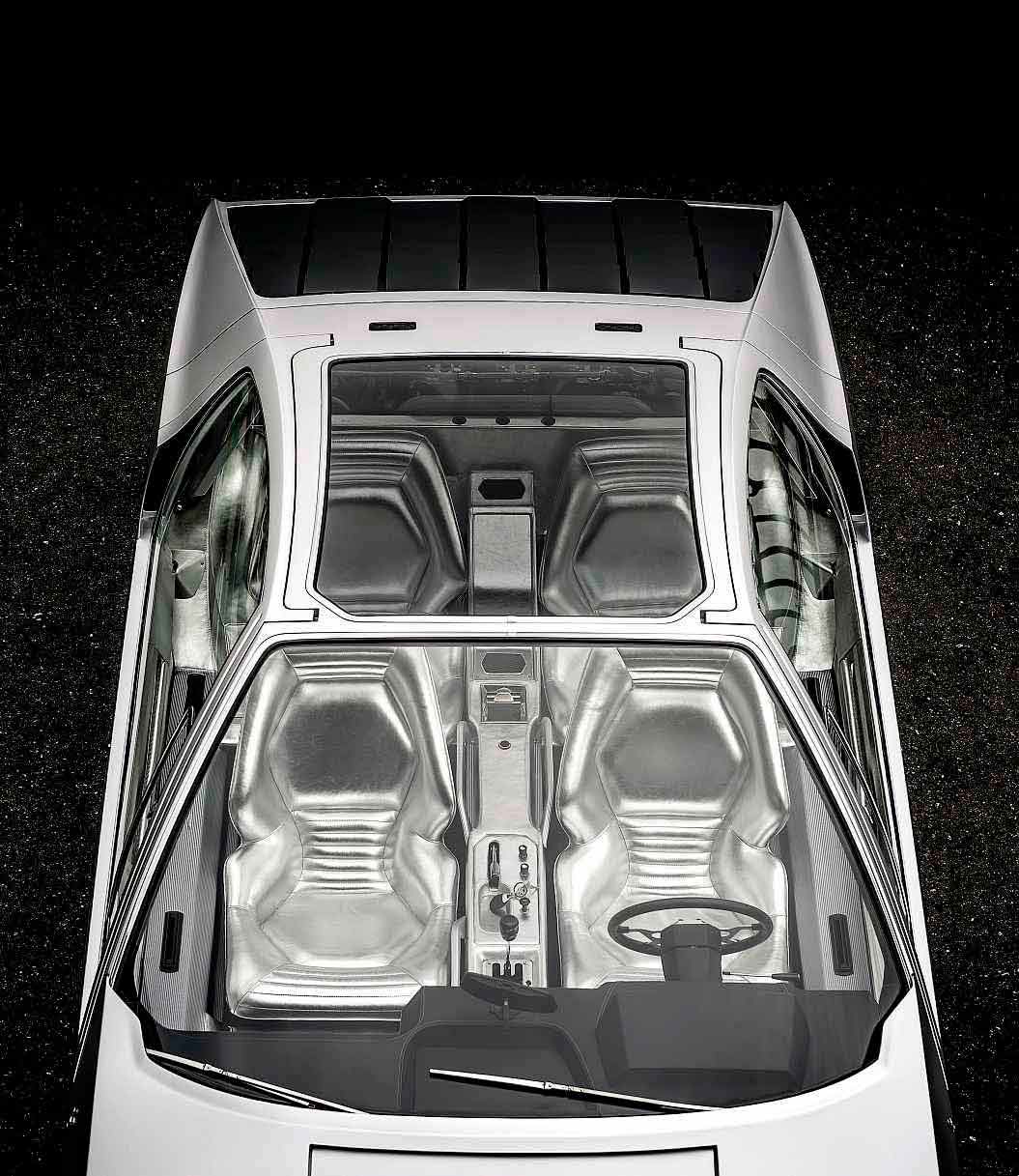

The most challenging aspect of the restoration was to repair the rusty body, with the aim of saving as much as possible of the original metal; the Marzal is all-steel apart from its alloy engine lid. Samples of the original paint were discovered in hidden sections, and matched so the panels could be resprayed in the correct colour. The interior had to be retrimmed to replicate the original silvery leather.

‘All that glass and the metallic silver of the leather combine so that even the cloudiest day feels like high summer’

The headlamps were rusted, but correct Marchals were found, and – thankfully! – all that glass had survived intact. ‘The most time-consuming part of the rebuild was to prepare and attach the front and rear bumpers, each made of many tiny pieces of rubber and leatherette, and each one screwed, or glued, to the support,’ recalls the curator of the collection. Opening the heavy door and dropping into the cockpit is like entering a world of enhanced luminosity. The colour of the car, all that glass, and the metallic silver of the leather combine so that even the cloudiest day feels like high summer. The seat is very comfortable, but you feel totally exposed.

The six-cylinder engine starts immediately and soon settles to an even idle, better in that respect than the Miura’s V12, though that car’s magnificent soundtrack is obviously absent. The clutch is light, though you have to remember the transmission’s back-to-front shift pattern. There isn’t much going on below 2000rpm and the three Weber 40 DCOE carburettors are recalcitrant, but once you pass the 2000 mark its voice deepens and the reciprocating masses smooth out. The engine is still being run-in, so redline forays are forbidden, but it is easy to perceive its underdeveloped quality.

Changing gear requires decisiveness and muscle, as in the Miura, though the suspension settings are not as hard and the steering is a little less direct too. The Marzal’s reactions, in general, are less immediate, though that’s befitting of this less extreme four-seater. Visibility behind is almost non-existent, but the view out-front and to the sides is like little else; I can’t help but imagine how Sir Stirling Moss felt while driving his naked Lotus 18 to victory at Monaco in 1961.

The Marzal feels like a noisy, if spacious, soap bubble, jostling along just a few inches above the tarmac, and I’m happy there isn’t too much traffic because I feel vulnerable. Thankfully the weather is cool, so it’s a comfortable temperature within the silver cockpit, but I fear that a summer’s day could be a challenge. As the Marzal was never fully developed, it’s not intended for regular long journeys. Yet it definitely feels like a good foundation for what might have been, and its most disappointing element is actually the sound of that peculiar engine. I’d love to carry on south to Monaco, and repeat Prince Rainier III’s lap of that hallowed street-circuit.

Of course, the Marzal concept was developed into a production car. It became the Espada, launched in 1968 as a 2+2-seater, equipped with a front-mounted, longitudinally orientated V12. ‘It was beautiful, but definitely a more traditional car,’ says Dallara. ‘We tried to keep as much as possible of the Marzal, but the decision to use the V12, positioned in front, changed the volumes within the car and also its proportions. We did our best to save the gullwing doors, but they were heavy, difficult to engineer and expensive to build, and the height of the bonnet, necessary to clear the engine, made them look like an ill-fitting hairpiece.’

It is reassuring today to see the Marzal, fresh from winning the Best of the Best Trophy at the Lamborghini Concours in Neuchatel, Switzerland, spending the day being as loved and respected as it deserves. It’s the perfect opportunity to recall that magic day on the streets of Monaco in 1967, when the Marzal stole the hearts of the most glamorous couple of the moment and stunned the world while becoming one of the most famous show cars ever built.

TECHNICAL DATA FILE SPECIFICATIONS 1967 Lamborghini Marzal

Engine 1964cc straight-six, DOHC, triple Weber 40 DCOE carburettors

Power 175bhp @ 6800rpm / DIN

Torque 132lb ft @ 4600rpm / DIN

Transmission Five-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

Steering Rack and pinion

Suspension Front and rear: double wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bars

Brakes Discs

Weight 1210kg

Clockwise from top Doors were difficult to repair; engine bay is a work of art; shift pattern is back to front; Bertone bankruptcy forced sale; yet more hexagons. Left, above and right Hexagons abound, both inside and out; 2.0-litre straight-six is half a Miura V12; gullwing doors, acres of glass and silver trim are pure sci-fi.