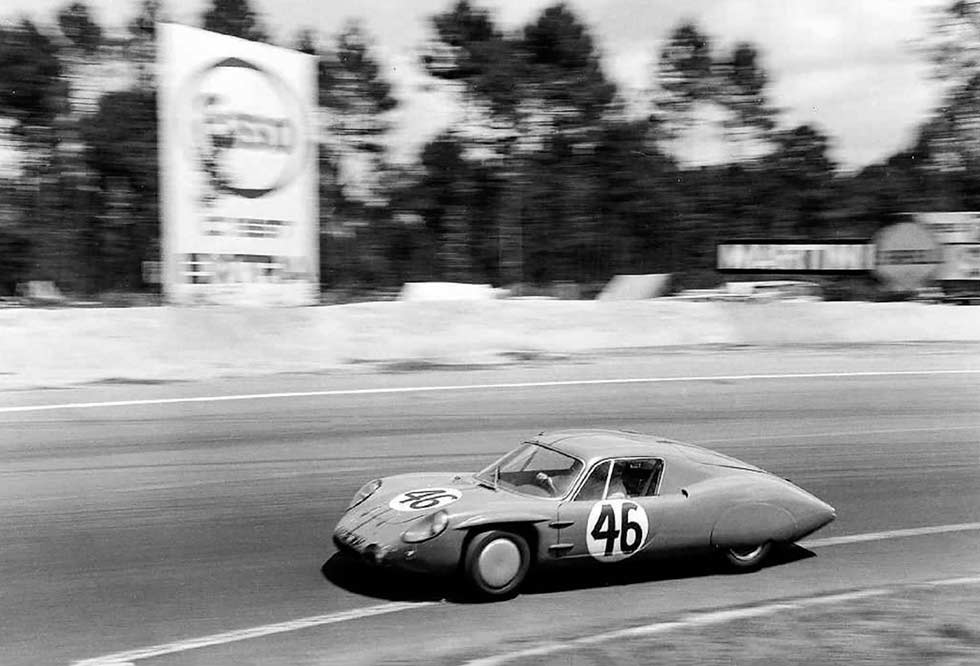

Sweet Revenge. Le Mans Alpine M64 French icon – back after 50 years. More than half a century since its win at Le Mans, the prototype conceived by Alpine and Lotus to beat René Bonnet is back on the track Words Mitch McCullough Archive images Renault Communication. Photography Chris Szczypala /@igiveashoot (action) and Tim Scott (static)…

WILD ALPINE M64 Le Mans star breaks cover after 50 years…

Colin Chapman wanted revenge. His Lotus 23 racers had been barred from the 1962 24 Hours of Le Mans for minor technicalities (in his view, at least), each of which he’d addressed (in his view, at least). After vowing never to run his cars at Le Mans again, Chapman turned his fury towards René Bonnet, convinced that the French constructor had protested the new mid-engined Lotuses to keep them from winning the Index of Thermal Efficiency – an award Bonnet coveted.

Journalist Gérard ‘Jabby’ Crombac suggested Chapman might channel his anger by assisting Alpine founder Jean Rédélé. Crombac knew Rédélé wanted to build a lightweight prototype to contest the small-displacement classes at Le Mans and, in the long term, win overall.

In Rédélé, Chapman found a kindred spirit – someone who shared not only his ambition to beat Bonnet, but also his philosophy. Like Chapman, Rédélé believed that performance was best achieved through the minimisation of mass. The pair discussed details of the proposed Le Mans prototype several times, and the best minds at Lotus, including Bob Dance, Keith Duckworth and Len Terry, were made available to Alpine.

Terry drew up plans for a chassis informed by that of the recent Lotus 23, but his design for the car dubbed ‘M63’ fell foul of the latest Le Mans rules; Rédélé’s engineers made the necessary alterations and added a backbone tube, a chassis element familiar to Alpine. Meanwhile, Rédélé himself approached Renault, which agreed to provide engines through Amédée Gordini. And the brilliant Marcel Hubert penned a sleek glassfibre body.

The car was successful right out of the box. With José Rosinski and Lloyd ‘Lucky’ Casner at the wheel, an M63 finished first-in-class at the 1000km Nürburgring in May 1963 – but triumph was followed by tragedy. At Le Mans in June, three M63s and six drivers were entered. No Alpine completed the race, and only five drivers came home, with Christian Heins killed in a fiery wreck after swerving to avoid the upturned Jaguar E-type of Roy Salvadori and the crashed Bonnet Aérodjet LM6 of Jean-Pierre Manzon. Another Aérodjet, driven by Jean-Pierre Beltoise and Claude Bobrowski, claimed the Index of Thermal Efficiency. It was a disaster, yet Rédélé, undeterred, was soon plotting his return to the Circuit de la Sarthe. At Alpine HQ in Dieppe a new car began to take shape, the team working to deliver a machine with improved stability and handling at very high speed.

The engineers kept the wheelbase and track of the M63 (90.5in and 50in respectively) but reverted to a spaceframe chassis more like that initially suggested by Len Terry and constructed from welded molybdenum steel tubes. The car that had performed so well at the Nürburgring was hardly a lumpen brute, but Marcel Hubert refined his design nonetheless, shortening it and reducing the frontal area to bring down the drag coefficient even further.

An 1149cc Gordini four-cylinder engine was installed amidships and the finished car, the M64, tipped the scales at just 648kg. It was a package that promised much, and at Le Mans in 1964 Roger de Lageneste and Henry Morrogh got the very most out of it: the pair completed 292 laps, covering 2436 miles at an average speed of 101mph while managing 21 miles per gallon. That was good enough for 17th overall – and the Index of Thermal Efficiency. The best Bonnet could manage was 23rd overall, three places behind an Alpine M63. Mission very much accomplished.

The de Lageneste/Morrogh car, chassis 1711, wasn’t done yet, however. A few weeks after Le Mans, the same drivers steered it to a class win at the 12 Hours of Reims. A parched and ravenous de Lageneste gulped down some Champagne immediately after the race, just before a call came over the loudspeaker to demand a victory lap. With bubbly sloshing about in his empty stomach, de Lageneste volunteered Juan Manuel Fangio, on hand as a guest of Renault, to do the honours, much to the delight of the crowd.

The car was later used to help Michelin develop its first radial racing tyres, and also in the development of an oleo-pneumatic suspension for Allinquant that was ahead of its time conceptually, but not perfected in its day. In the autumn of 1965, chassis 1711 was rolled back into the Alpine factory and fitted with the dramatic tail fins used on the M65 and A210. The following year the car was put into long-term storage.

It re-emerged in 1977 and was acquired by Bugatti enthusiast Jacques Ohana, only to disappear again for decades. Ohana always intended to restore it, but by the time of his death little had been done. His family sold the car at auction in 2014 and it was displayed at that year’s Le Mans Classic before becoming available again in late 2016 – which is where I come in, I suppose.

I’ve been interested in Alpines since the early 1970s, but when my wife Kim and I decided to buy our first classic car, she was the one who insisted on an A110. An aggressive search landed a factory-prepared Group 4 rally car in 2006 and we were immediately hooked – suddenly in deep enough that we thought nothing of flying from New Jersey to Paris for Rétromobile in 2008 to buy wipers and other parts.

While there, we visited L’Atelier Renault, a café on the Champs-Élysées that happened to be showing a number of Rédélé’s creations. We marvelled at the various Le Mans prototypes but assumed they were national treasures, not for sale to anyone – and most certainly not to an American.

One day in 2016, Kim and I talked about these cars again, and that very night I sat down at my computer and saw it. I couldn’t believe my eyes: chassis 1711, to be sold at auction in Paris in two weeks. Pack the bags! At the auction venue we walked into a brightly lit underground garage where the M64 was on display. It had such presence, and its condition was astonishing. Though it had recently been painted and prepped for sale, most of it was clearly original.

The Plexiglas hatch had broken during shipment but we knew it could be replicated, and there was little else to cause concern. There was work to be done, of course, but nothing beyond the understanding of an enthusiast familiar with a Formula Junior or early ’60s sports-racer: spaceframe, mid-engine, dual Weber 45 DCOE carburettors, Girling brakes, Hewland gearbox, Dauphine steering box, Renault wheel bearings.

The car was fitted with the original wheels drilled for aerodynamic covers, but if replacements were needed the rear wheels from a Lotus 23 would bolt right onto all four corners. Windscreen, hardware and trim – all shared with the A110. I was aware that the Gordini engine could present something of a challenge to an owner based 3500 miles from France but, as Le Mans prototypes go, the M64 seemed like it would be an easy car to own. The winning bid was placed.

It was a big day when the car arrived, cleared ports at Newark and was unloaded in the driveway. For a while it stayed at home, partly because we hadn’t quite figured out what to do with it, and partly because we enjoyed just looking at it. Eventually we concluded that there was one event the Alpine simply had to attend: the 2018 Le Mans Classic.

The first stop on the long road back to Le Mans was Graham Long Engineering in Clifton, New Jersey, where everything critical or likely to wear was rebuilt, repaired or replaced.

‘Don’t drill any holes, don’t fill any holes,’ advised our friend Tom McIntyre, and his words have kept us honest. We’ve not replaced the partially broken air vent in the centre dash. The M64 has a beautifully integrated roll bar, but the rules don’t require a roll cage, so we haven’t added one. With great reluctance we’ve changed the shift linkage, stripping off the red rubber boot and painting the shafts military grey to match the old ones.

The original fuel tanks – the M64 has two, with fillers on both sides – have been retained, but we’ve installed custom-designed ATL bladders inside. A new exhaust header has been fabricated with reference to period photos. The gauges, switches, dash and seat all appear correct and have needed little attention.

Mark Cramer, who runs Remarc Restorations in bucolic Upper Black Eddy, Pennsylvania, was given the task of solving the problem of the broken Plexiglas hatch. He heated and flattened the old one to make a perfect double from Lexan. We’ve considered whether the body should be returned to its 1964 appearance, but replacing 1965 bodywork with 2018 glassfibre intended to look like 1964 really isn’t something we want to attempt. And we like the perky tail fins. A crossbar has been added for a shoulder harness, but we’ve been able to match the original welding style, paint the bar and smudge it up with dirty hands to make it look like it’s been there for 50 years.

‘The moment I centre the steering wheel the car reveals Itself to me fully. It is an arrow piercing the air, unwavering’

Fifty years… On the morning of our first test it is not lost on me that this car has not been driven on a track in half a century. I sit warming the engine in the paddock at Monticello, a picturesque private circuit two hours north-west of New York City, telling myself that our preparations couldn’t have been any more thorough.

I cinch up the new sabelts, tilt my head to pull on the unwieldy helmet and HANs combination, slide the gearstick over and down into first, and move down to pit-out, full of anticipation.

As I approach, the flagger smiles and immediately signals that I’m good to go, no need to stop. I’ve got Monticello’s south Course completely to myself. I pull onto the track and into a tight right – and discover immediately that the Gordini engine will hardly run below 5500rpm, the car chugging around what ought to be a sweeping, fast right.

In order to prolong the life of the engine, it has been deemed sensible to keep the revs below 8000, but, as it turns out, that’s more than enough to get a sense of the car’s potential. it lugs and spits as I navigate another tight right, the aptly named Patience. Then it happens: I find second as I enter a set of s-curves called Prudence, the engine clears and the M64 surges ahead.

I power through the left-hander, the M64 on rails as it moves left to right and then round a long, hard left. It feels similar to a Lotus 23B, only more stable and a little more substantial. The steering is light and free – rather like that of an Alpine A110, unsurprisingly. After a short break the car has an opportunity to really stretch its legs on Monticello’s full, 4.1-mile circuit. I turn onto the 1200m back straight and the moment I centre the steering wheel the car reveals itself to me fully. it is an arrow piercing the air, unwavering as it flies across the tarmac.

I won’t pretend to know how the car must have felt on the limit in 1964; even a Roger de Lageneste full of Champagne could have taught me a thing or two about racing. But as I flash towards the kink about halfway down the straight I think: maybe this is a small taste of what it was like. The M64 feels ready to go a very long way, very fast. Bring on Le Mans.

‘BOTH RÉDÉLÉ AND CHAPMAN BELIEVED PERFORMANCE WAS BEST ACHIEVED THROUGH THE MINIMISATION OF MASS… AND BOTH WANTED TO BEAT BONNET’

‘AS LE MANS PROTOTYPES GO, THE M64 SEEMED LIKE IT WOULD BE AN EASY CAR TO OWN. THE WINNING BID WAS PLACED’

TECHNICAL DATA FILE SPECIFICATIONS 1964 Alpine M64

Engine 1149cc Renault Gordini four-cylinder, DOHC, two twin-choke Weber 45 DCOE carburettors

Power 105bhp @ 7000rpm / DIN

Torque 94lb ft @ 5350-5500rpm / DIN

Transmission Hewland five-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

Steering Rack and pinion

Suspension Front: double wishbones, coil spring/damper units, anti-roll bar / Rear: trailing arms, horizontal top tie-rods, coil spring/damper units, anti-roll bar

Brakes All Drums

Weight 648kg

Top speed 150mph