Greyhound meets Aceca: AC’s sporting siblings back-to-back. AC’s brilliant fixed-heads Can the Greyhound match the Aceca? The AC Greyhound has long lived in the shadow of the Aceca. James Page finds out how it compares today, but there’s a twist in the tale. Photography Tony Baker.

Between the end of WW2 and Carroll Shelby ensuring that, for the wider public at least, AC would for ever mean Cobra, the Thames Ditton firm produced a brilliantly distinctive range of cars. As the 1960s dawned, customers could choose between a fabulous roadster in the unforgettable shape of the Ace, a hugely capable GT in the Aceca, and a sporting but practical 2+2 in the Greyhound. The open car, of course, remains by far the most celebrated of the three, but the charismatic closed models deserve their share of the limelight.

The Greyhound was the spiritual successor to the 2 Litre, and while their respective launches were separated by not much more than a decade, AC had packed an awful lot into the intervening years. With a chassis based on a pre-war Jaguar design and an in-house engine that could trace its roots back to 1919, the charming 2 Litre played a vital role in re-establishing car production at AC following hostilities. By the early 1950s, however, its price had crept over the £1000 mark, which meant a steep rise in Purchase Tax, and in any case the company’s focus had shifted elsewhere.

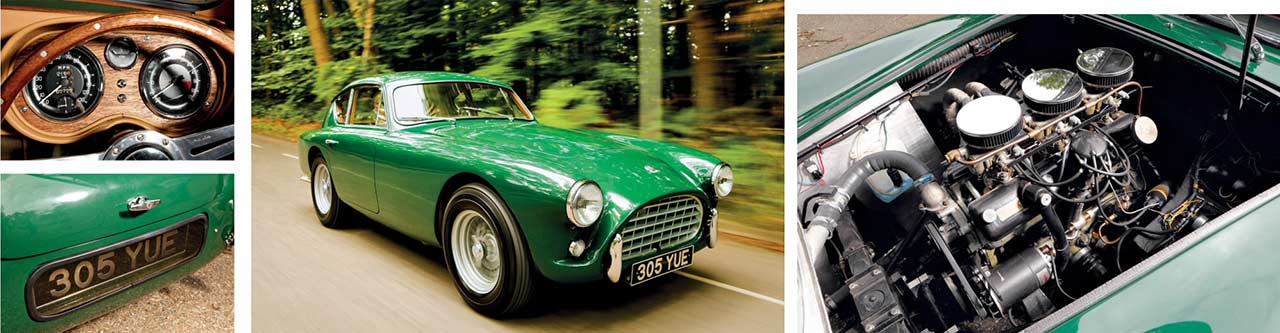

In 1953, it launched the Ace. By equipping a roadgoing derivative of John Tojeiro’s beautiful little sports-racer with an uprated version of the 2 Litre’s six-cylinder engine, AC created a design for the ages. And then the following year it made an attractive GT out of the roadster by introducing the Aceca, both models representing an extreme departure from the 2 Litre in terms of styling and engineering.

But while the Aceca perfectly satisfied the needs of the more refined clientele who desired an Ace but wanted a roof over their heads – or, as The Autocar put it, ‘who sometimes needs to arrive unruffled at a formal occasion’ – it was still only a two-seater. Production of the 2 Litre trickled on until 1956, after which it would take three years for the Hurlock family to present a new take on the four-seater theme.

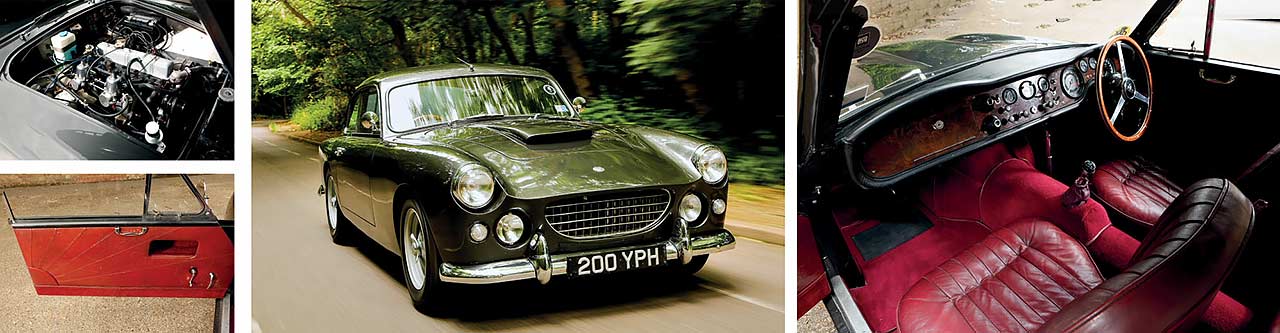

The Greyhound prototype was first shown at the 1959 Earls Court Motor Show, and employed a lengthened Aceca chassis with bodywork that was styled by chief engineer Alan Turner. For production cars, which started to appear the following year, there was a stronger square-section chassis in addition to a facelift that encompassed restyled rear windows and a smoother nose. Also, the spotlights moved from being within the grille – an upturned Ace item – to either side of it, and there was a stronger frame to support the aluminium body.

The increase in size over the Aceca – it’s 10in longer and 4in wider – is instantly noticeable when you see the two next to each other, but it has an impressive stance and plenty of presence. In profile, you notice the squarer waistline plus the shallower slope to the large rear screen. Wander around the back, meanwhile, and from a three-quarter angle it carries particularly strong echoes of the Aston Martin DB4.

Clockwise, from main: Aceca’s wonderful lines are best showed off in profile; transverse leaf spring is prominent within the engine bay; cosseting cabin – note crooked lever.

Not everyone is a fan. A certain Martin Buckley wrote – a long time ago, admittedly – that: ‘At best, the fastback shape lacked harmony. At worst it was an unforgiveably clumsy piece of work from an outfit that had given us such great-looking machines as the Ace and Aceca.’

It’s certainly a very different proposition to the more compact and curvaceous Aceca, which boasts a timeless beauty that few cars can match. The featured example looks particularly good minus its bumpers, even if the overriders would do little to protect the rear wings.

In the metal, however, the Greyhound’s lines come together far better than they sometimes do in photographs. I like it, and seeing it with its two-seater stablemate it’s almost difficult to believe that they were sold alongside each other for three years. In period, it would have represented a far more contemporary offering than the Aceca. It was a design for the 1960s, rather than one that – however gorgeous – was most definitely a product of the previous decade.

The featured Greyhound belongs to Reginald Warlop. He has a varied car-owning past that includes an MGB – “It rusted everywhere” – and even a Pembleton three-wheeler, but he’s always had a soft spot for the Thames Ditton marque: “I love ACs, and particularly Cobras. I like to draw, and when I was 16 I was always sketching Cobras. And Lamborghini Miuras, too! I’ve always been into ACs, though, so I liked the Greyhound, but I’d only previously seen one at Goodwood. I was drawn to its structure, design and light weight – an Aston, for example, would have been much heavier.

“I bought it three years ago without having seen it. It had ended up in Sweden and needed to be recommissioned. It was ideal for the kids because we could all go to shows in it. In fact, as soon as it was ready in September 2014, I took it to the Concours of Elegance at Hampton Court. I get a lot of use out of it.We’ll go out most weekends, and I’ve taken it to Knokke in Belgium, which is where I’m from. It’s amazingly reliable, and has let me down only once. It’s great on the motorway – there’s lots of space and it’s comfortable, plus it has a pretty big boot, so it’s a sensible touring car.”

But all is not as it seems with this particular Greyhound, and to explain requires an understanding of the engines involved. Having introduced the Aceca with yet another update of its own venerable ‘six’ – this time with triple SU carburettors and 85bhp – AC switched to Bristol power in 1956. That arrangement lasted through to the Greyhound, with the majority of examples using either the 1971cc or 2216cc version of Filton’s cross-pushrod unit.

Clockwise, from left: less ergonomic cabin, but there’s more room; nose was restyled after the prototype’s Motor Show debut; sunburst door cards; 2498cc Triumph straight-six is a good fit.

When supplies from Bristol dried up, a handful of late cars were fitted with AC’s engine – making one last appearance and by then uprated to 105bhp – and it is thought that another Greyhound was fitted with an experimental flat-six, but that never got past the prototype phase. There was also talk of fitting a V8 – either Edward Turner’s little Daimler unit or the allalloy Buick/Rover powerplant.

As it was, production came to a halt in 1963 after only 84 cars had been built – the Ace and Aceca were discontinued at the same time. With Greyhounds then slipping out of fashion for a number of years, people would seek them out solely for their Bristol engines – the 1971cc 100D2 was particularly desirable. Once that had been plundered for the benefit of an Ace, Aceca, Frazer Nash or whatever, the remains would be sold on and often fitted with a more affordable and available drivetrain, which at least enabled the car itself to survive.

“Greyhounds were losing their engines at a time when they were seriously under-appreciated and their engines were worth more than the cars,” explains John Goose, AC Owners’ Club stalwart and Greyhound custodian. “Happily, this has now changed. They’re becoming more appreciated and more valuable. This means that they are less likely to be cannibalised, and restoration costs, which can be very high with all that aluminium bodywork, become financially justifiable.”

Many Greyhounds had already sufffered that fate, however, and, in the case of Warlop’s car, there’s an instant giveaway without even having to lift the bonnet. In place of the standard gearknob is an unmistakably Triumph item, complete with overdrive switch. “I need to find another gearknob, really,” he says with a smile. “Maybe I’ll just make one!”

Goose confirms that the Triumph ‘six’ is the easiest replacement: “It’s in period and drops in without you having to alter the engine bay too much. A couple of cars have been fitted with Ford’s 2.6-litre unit – in fact, the factory made a prototype using that engine when Bristol was moving to V8 power and AC had to look elsewhere. There are a couple in the US with Ford V8s, too, although I would have thought that’s rather heavy for a relatively lightweight car.”

In fact, Goose himself knows the benefits of owning a ‘hybrid’ Greyhound: “I have the prototype/ first production example with a Bristol 100D2 unit, which I love dearly but I always wondered how it would be with twice the litres and horses. When an engineless car became available, I grabbed the chance and installed a Rover V8 with a nice camshaft and four-choke Weber. It’s wonderful. The chassis is well able to cope with V8 power.”

In the meantime, Warlop has been posting on a Bristol forum in an attempt to track down the car’s original powerplant – 100D2 number ‘1129’, which these days is apparently fitted to an Ace – but for now he’s delighted with the Canley replacement: “I can go flat-out and drive it for long distances without worrying about something expensive going wrong. It’s in the spirit of the car, too. It’s a British ‘six’. It’s not like putting a Pinto engine in a Ferrari.”

He may have refurbished his Greyhound, but Warlop wisely left the interior alone. The original trim has a fabulous patina, from the handsome sunburst doorcards to the leather seats and carpets. The dashboard is slightly random, with unlabelled rocker switches here and there and plenty of auxiliary dials, while the ventilation controls are a stretch away to the left. At 5ft 7in, I’m able to get relatively comfortable once I’ve climbed into the rear seats, even if legroom is marginal. “If there was a fault with the Greyhound,” Alan Turner told C&SC in 1991, “it was that the space was a little bit generous for a 2+2. So, in many people’s eyes, it was a four-seater with cramped rear seats, rather than the original conception of a 2+2 with generous seating for children. It fell between two stools.”

The Aceca boasts a much more ordered dashboard. Although the steering wheel is similarly vertical in both cars, the driving position does feel a little more dated in the earlier model, with that wheel resting in your lap and a gearlever that is bent through various angles on its way out of the transmission tunnel. Even so, with its mixture of leather and wood, it’s a very pleasing cockpit in which you feel nicely cocooned. Beneath the metal, the Greyhound received various mechanical upgrades over the Aceca.

Whereas the earlier car had a transverse leaf spring at either end plus cam-and-peg steering, the four-seater revelled in wishbones all round with coil springs and telescopic dampers. There was a new rack-and-pinion system, too.

That translates into sharper reactions than the Aceca, especially around the straight-ahead, with the Greyhound turning in well and changing direction keenly. The Triumph engine in Warlop’s car has impressive low-down torque, too. It responds instantly and suits the car well, even if the engine note is more gruff than the crisp, cultured bark that the Bristol unit produces once you start pressing on.

This Aceca’s ‘six’ has been upgraded to an ex-Arnolt Bristol powerplant, and once you’ve explored the lengthy throttle travel the acceleration is impressive and thoroughly addictive. The rev counter is redlined at 5500rpm, but in truth you don’t need to venture far beyond 4000rpm to make swift progress. The gearchange, too, is wonderful, a mechanical and precise movement that the slightly woolly Triumph shift in Warlop’s Greyhound can’t match.

The speed – from a standstill, 60mph comes up in about 10 secs – ‘feel’ and spine-tingling noise, which reverberates around the compact cabin, add up to make driving a really good Aceca an unforgettable and intoxicating experience.

Despite its attempts to be a more refined option than the Ace, it is still first and foremost a sports car. Yet, despite what some reports over the years would have you believe, the Greyhound is by no means overshadowed. It’s less overtly sporting than the two-seater, but it had an even more luxurious and practical brief to fulfil. It handles precisely, stops well with its combination of discs up front (an option on the Aceca from 1957) and drums at the rear and, on 185HR15 radials, feels nicely composed.

“Towards the end of its development,” said Turner, “a car was road-tested by The Motor, much against my will because I didn’t think it had the right wheels or tyres. In the road test it was reported that it had a tendency to wander at speed, which we believed was caused by the 15in wheels and crossply tyres that were fitted. I think the car was spoiled for many by that article.”

Clockwise, from main: compact ‘hatchback’ vs Aston-esque saloon; larger Greyhound has a squarer profile; headroom is fine in the rear seats, legroom is rather less so.

Mud sticks, and then there was its cost. As Goose points out, for the asking price of £3185 – an Aceca Bristol was £2561 – you could have bought a Jaguar plus a couple of Minis. Its low profile counted against it, too. In later years, when most people thought of AC they pictured a Cobra or an Ace. If they thought of a closed AC, it was an Aceca, and even though prices for that car are now firmly into six figures, it seems absurd that you can still buy a good one plus a Greyhound – at about £50,000 – for much less than a single Aston Martin DB2/4.

It’s a shame that Greyhound production stopped when it did, and the car didn’t have the chance to compete for longer with rivals from the likes of Aston, Jensen and Alvis. It’s fascinating to contemplate it being fitted with a lightweight V8 and possibly forming the basis for the next generation of ACs, but the 2+2 deserves its place alongside the illustrious Aceca. “I have no intention of selling it,” concludes Warlop. “Once you have a car like this, there’s no need to buy another one.”

Thanks to Everyone at Brooklands Motor Company Group, which is selling the featured Aceca: www.brooklandsmotorcompany.co.uk; Brooklands Museum: www.brooklandsmuseum. com; AC Owners’ Club: www.acownersclub.co.uk

Clockwise, from left: tall Bristol unit topped by triple Solex carburettors; front looks even better without its bumper; recess for rear numberplate; simple binnacle for the major instruments.

Gently does it

Steve Gray at Brooklands Motor Company Group was entrusted with renovating Warlop’s car: “Stripping it took about 60 hours, and it was then masked and very lightly media-blasted. Abrading that bodywork with anything other than a stainless-steel wire wheel and an orbital sander using a soft interface pad will cause heat distortion, plus possible contamination and delamination around the edges. We use a wet strip and then media, because the 16swg body can be 18swg or 20swg in places, and will appear like lace when corroded.”

With Greyhounds that have lost their engine, Gray usually sources the correct type: “The 2.2-litre unit is available from Bristols that are beyond salvation. Rebuilds will cost £15-30,000 – and up. If you’re buying a Greyhound or Aceca, though, the bodywork is the major area of expenditure.”

‘THE GREYHOUND IS A VERY DIFFERENT PROPOSITION TO THE CURVACEOUS ACECA’

{CONTENTPOLL [“id”: 72]}