An R-type Continental for the 1970s? The controversial Camargue: Rolls-Royce’s brave new look. Rolls-Royce Camargue Buckley on the luxurious leviathan. Rolls-Royce’s unloved Camargue could be due a renaissance, says Martin Buckley as he reassesses the majestic former range-topper. Photography James Mann.

Statement motor cars famed principally for their rarity and price always seem to suffer the longest, cruellest and most pernicious periods of decline. They have the furthest to fall, and hit the ground harder. So it was with the Camargue, the most self-consciously glamorous Rolls-Royce of all, and the most misunderstood.

Looked at logically, this is a car that, by virtue of its relative scarcity – 526 production examples plus half a dozen prototypes – and exclusive image should have been the natural 1970s heir to the Bentley Continentals of the ’50s and ’60s. Somehow, that has not yet come to pass. With a list of first owners that includes the Shah of Iran, Shirley Bassey and Bernard Manning, this uncompromisingly angular two-door coupé has never shaken off its image as a choice for the showy rather than the suave. It’s a car not so much for crossing Europe in speed and silence as for cruising Wilshire Boulevard at 35mph, luxuriating in the world’s best split-level aircon – and the envious glances of the poor unfortunates who could only afford a Corniche convertible.

There are echoes of FAB 1 about the Camargue’s colossal front grille and twin headlamps; it corners better than you might imagine for such a big car.

In truth, it was more eminently suited to both activities than any Crewe product before it, a magnificent blend of traditional craft, uncompromising luxury and technology. It sported a Pininfarina body that, although controversial from the off, also has a presence and majesty that is now coming into its own. Prices are on the move: the Camargue may yet have its day. Introduced at the beginning of 1975, its launch was delayed by both the 1973 fuel crisis and, more critically, Rolls-Royce Ltd’s 1971 bankruptcy and the subsequent hiving off of the car-building operation as a separate entity. At Pym’s Lane there was suddenly an imperative to make a profit rather than operate as a ‘Prestige’ division that just about covered its costs.

What had begun as a project designed to replace the Mulliner Park Ward/Corniche Coupé (which was selling well) therefore evolved into an idea for a super-luxury model that would run alongside it. Working on the basis that Rolls-Royce could only move upmarket rather than down, the Camargue was designed to sell for a third more money to a clientele who were more image than price sensitive. At just under £30,000, the Camargue was the price of two Silver Shadows and even substantially outranked the massive Phantom VI limousine.

The Camargue was very much the pet project of Rolls-Royce’s then-young managing director David Plastow. Mindful of the long waiting lists and how much buyers were prepared to pay over the odds for ‘delivery mileage’ Shadows in the early ’70s, he had identified a healthy appetite for a premium-priced coachbuilt car as long as it looked sufficiently individual. It would need to have a more international flavour that would communicate the notion that even in the troubled post-crisis ’70s Rolls-Royce was here to stay.

The germ of the idea for an ultimate personal car had been sown in the late ’60s by the Bentley T1 built by Pininfarina for the tycoon James (later Lord) Hanson. Granted, this ungainly fastback was not conventionally attractive, but it had captured buyers’ imaginations. With a long history of producing bespoke R-R and Bentley designs for private customers, it was the natural choice of stylist. Sergio Pininfarina was so pleased to be working for the makers of ‘the best car in the world’ that he reduced his usual fee.

In October 1969, young Pininfarina stylist Paolo Martin was tasked with producing a set of proposals, his brief being to produce a two-door saloon with superior passenger and luggage space to the two-door Shadow. Other than being required to produce a shape that would not quickly date, he was given a free hand within the engineering parameters. By January 1970, he’d come up with four different styles (plus two variations of front and rear treatment) for evaluation by Fritz Feller and John Hollins of Rolls-Royce.

They came down in favour of a compromise between three different proposals, with a much wider radiator than had ever been fitted to a Rolls-Royce, but without the rectangular headlights (which would not have passed American regulations) or the contrasting black panel below the side windows that Martin had incorporated as a way of lowering the waistline and disguising the significant depth of the scuttle. What no one knew at Crewe was that Martin was already working on a similar design for Fiat (the 130 Coupé) that did have the famous rectangular lamps when it was launched in 1971.

He also did a version with a Bentley grille and concealed lamps; there is an argument that says the shape better suited the round-shouldered radiator. In the early ’70s, though, the marque was in decline. There was much less awareness of it in North America, which was intended to be – and was – the Camargue’s principal market.

The model name linked the car to the luxury playgrounds of the South of France in the same way as Corniche, although for a while it looked as if it was going to be called Corinthian. Internally it was always Project Delta – the first official production Rolls-Royce styled by an outsider, a fact not greeted with universal joy by the incumbents of Crewe’s highly capable body-design department where Fritz Feller had only recently replaced John Blatchley as chief stylist.

In fact, the Camargue was to be a Royce of many ‘firsts’. None before it had been built to metric dimensions or featured a bonded front windscreen, curved side glass or fibreoptics; the red marker lamps on the edges of the front wings helped the driver to judge the Camargue’s 6ft 3½in breadth, 3in wider than the Shadow. Apart from the Corniche-type brushed-aluminium wheel covers, surprisingly little of the body furniture was shared with other models.

If the Italians were styling the body, they certainly would not be building it. As with the Corniche, the Camargue was to be constructed on a modified Shadow platform by Mulliner Park Ward in Willesden. Pressed Steel supplied the floorpan to MPW, where it was mated to a body that, like the Shadow, had mild-steel wings and roof but alloy opening panels. The shells were then sent up the M6 to Crewe for priming, rust-proofing and the fitting of the major mechanical components before being returned to Hythe Road for completion.

Each Camargue took six months to build (it could take one man a week just to fit the rear seats) and the big, flat panels were not easy to make. In fact, of the 526 cars produced through to 1986, only the first 176 were finished by Mulliner Park Ward. In 1978, Motor Panels of Bedworth was contracted to build the bodies and the Camargues were then completed at Crewe. By that time, the cars had acquired the rackand- pinion steering of the Shadow II. From ’79, Camargues and Corniches had the improved mineral-oil rear suspension, with modified trailing arms and better location, that would feature on the still-secret Silver Spirit.

The Camargue’s best year was 1980, when 98 cars were sold, and ’83 the worst with just 19. This Cotswold Gold car dates from 1985 and must be one of the last to have been sold new in the UK. It would have set its first owner back £80,000.

The truth is, the Camargue is a superb car in many ways and always was. It is a shape very much at the mercy of colour choice (I love the gold, one of a range exclusive to the model) and the way that light and shade play on its bold, flat panels. If only Pininfarina had been allowed to drop the height of the scuttle and do something more imaginative with the headlights, it might have had the slinky, svelte appeal of the 130. But the longer you live with a Camargue, the better it looks – particularly its elegant full-on side or that simple, powerful three-quarter rear. Only in the crisply chopped-off tail can you see strong echoes of the Hanson Bentley that inspired it.

It’s even better on the inside. The doors, with those oddball press-down handles, are massively long and heavy, giving easy access to the deeply bolstered front seats and one of the roomiest and most regal rear compartments of any two-door.

It feels noticeably wider than a Shadow, with perfect views front and rear and a driving position that is both relaxed and commanding, with armrests built into the seats and that delightful two-spoke, thin-rimmed wheel. There is 450sq ft of best-quality Nuella hide here (including the headlining) perfectly complementing Martin’s aircraft-inspired dashboard, which imaginatively used surface-mounted rather than flush instruments as a way of making the standard gauges look different. Every detail of wood, chrome and leather is immaculately resolved and silky in operation in a way that set Rolls-Royce apart from any other low-volume car builder.

A flick of the tiny Yale key in the traditional switchbox brings the all-alloy 6.75-litre V8 to whispering life. Its power and torque were never officially disclosed yet, like all but the first 31 Camargues (and most of the export ones) this example has a four-barrel Solex in place of the twin SUs, which teases out some useful additional power. It more than does the job, swishing this 5500lb coupé away with a smooth, suave, addictive nonchalance that is the very essence of what makes any Shadow derivative so impressive. This engine must represent the pinnacle of refinement for the post-war carbureted V8, and the same goes for the gearbox to a certain extent.

Set the electrically assisted column shift to ‘D’ and from that moment on you never really give the GM 400 unit another thought. Now, level the small, beautifully smooth throttle and feel the unobtrusive thrust just keep on coming until you are doing well north of 100mph, what engine noise there is muffled by tyre rumble.

It will cruise handsomely at quite a lot more than that, still with the aircon providing a perfect climate where there is never any cause to do anything as uncouth as lower a window. A decade or more in the making, this system, with its myriad sensors and air-blending valves, feels totally contemporary. It was a fund of fascinating Camargue trivia; I always loved the idea that it cost as much as a Mini to install and had as much cooling capacity as 20 domestic fridges.

This 5001-series model has deliciously smooth and accurate power steering combined with an impressive lock to give the car perfect town manners. More importantly, it has that very particular Rolls-Royce ability to insulate you from the rest of the world (even when the rest of the world is staring at you) at all speeds. That is possibly as much to do with the hypnotic effect of the view down the bonnet as it has with the intrinsic smoothness or quietness of the ride.

It’s not a GT, but the Camargue undoubtedly tours grandly. Yes, it dips its nose when pressed but you have to be going quite quickly to make it feel untidy or uncomfortable or begin to slither about on the seats (interestingly, Plastow specified his own Camargue with cloth seats) or even make the tyres squeal. In any case, this is not a car to handle roughly or draw attention to yourself.

If Jaguar and Mercedes struck better dynamic compromises, then they had the advantage of producing much lighter vehicles. Driven within its parameters, the Camargue is surprisingly capable in its soft, gentle way. Yet it doesn’t do anything better than a Spirit of similar vintage, and you can buy one of those for a fraction of the £42,000 that Vintage & Prestige is asking for this well-cared-for 77,000-mile example.

None of which is the point. The Camargue makes a statement like no other Rolls-Royce and, like so many objects that teeter teasingly between ugliness and beauty, there is something about it that is undeniably très chic.

‘ITS SMOOTH, ADDICTIVE NONCHALANCE IS THE ESSENCE OF WHAT THE CAMARGUE IS ABOUT’

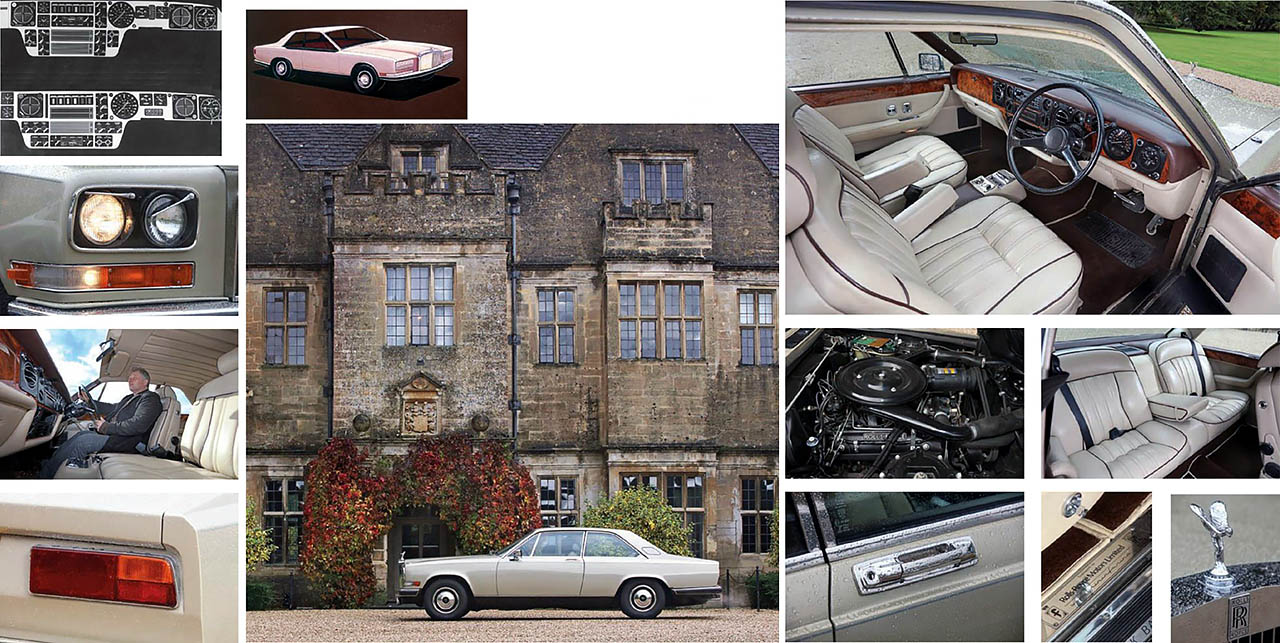

Clockwise, from below: Camargue now has a classiness that was lacking in its youth – crisp profile is its best view; neat rear cluster; Buckley luxuriates in the split-level aircon; wash-wipe on lamps, as you’d expect on a car that cost 80 grand – this 1985 model was one of the last. Clockwise, from top: lavishly appointed cabin with aircraft-style fascia; the back seat was roomier than a Corniche; R-R sill plate says ‘designed by Pininfarina’; quirky, pressdown door handles; all bar the first 31 Camargues had a four-barrel Solex carb to feed 6750cc V8. From top: Martin’s draft for a Bentley Camargue (one was made); vertical and horizontal instrument layouts.

Crafting the shape

“Being in that period an employee of Pininfarina – and Italian,” says stylist Paolo Martin, “I feel a little uncomfortable in describing the phases of the project. Not so much because of the make of the car and the personality of the employer, but because of the ways, times and methods in which it took place, which were incredible.”

As Martin recalls: “The first drawings were run at the end of 1969; a complete Corniche arrived in the workshop in 1970. There were no constructional or dimensional drawings of any kind, just a list of functions and general characteristics to apply to a future model. The car was dismantled and sectioned, retaining the underbody frame. It was the same process for all of the other usable parts and sub-groups.

“Then I began to work: I would like to say that the whole project up to the realisation of the prototype lasted no more than three months. With the support of Franco Martinengo [then director of Pininfarina Centro Stile] I designed all the bodywork, steering wheel, dashboard, interior, seats and exterior lights – everything in 1:1 scale. The lines were tense and deemed to be different enough compared to the car’s sister models, but I tried not to disrupt its personality too much. I must confess that the design of the Fiat 130 Coupé was also being drafted, and there is a commonality of lines even if it is a very different type of car.

“The most difficult part was interpreting the functions of the tools and equipment required.

Everything was in inches, complex dimensions that we were unfamiliar with: nobody knew English or the technical terms and nobody wanted to go beyond the specified measurements. So, reluctantly, we began the first and unique designs by using a ‘collage’ technique with the imperial and metric – as well as two full-sized versions of the cockpit with the instruments positioned alternately horizontally and vertically. Throughout the project, there was not the slightest hiccup: no change, no rethinking and the prototype was executed extremely quickly!

“For me, it was really satisfying and always a great experience – unique and unrepeatable.”