Luxury, Franco-German style. The Giant Test team analyses two prime contenders for the growing European middle-class market. The British middle class has, by and large, held fast to its ideals through all the ordeals it has been called upon to bear. One of its principal ideals is that it shall drive cars which are sober outside, luxurious inside, and sufficiently well known by the rest of the world to establish without question the status of their owners. Among British cars in this category the Rover stands supreme, although the more sportingly- minded prefer the Jaguar. There used to be many more British contenders, but by process of merger or marketing ineptitude they have fallen by the wayside, leaving a small but tempting niche for the foreigners to slide into.

Undoubtedly the foreigners who have made the best thing out of this situation have been Mercedes. Despite the fact that import duties make their cars ludicrously expensive here (and they do not deign to cut their profit margins to counteract this) they make exactly the sort of car the middle class — in their case, the entire European middle class — wants. A truer picture of how Mercedes stand in the markets of the world may be gauged by the fact that in neutral Switzerland, the current 250 costs less than the Rover 3.5; here, it costs nearly £1000 more.

Citroen have always been hampered in selling the big ID/DS in the same British market because of its singular looks and idiosyncratic, if advanced, engineering. But longevity (equated in the mind with thorough development and reliability) is another factor the market treasures, and here the DS wins hands down, for it looks unchanged to the inexpert eye.

Taken on the grounds of cost and of people space, the Mercedes 250 and the Citroen DS21 Pallas that we compare here must compete with the big Rovers and the 420G Jaguar. Bred as they have been in very different environments, it is interesting to see how they face up to the challenge. As is well known, European tax structures favour small, efficient engines, while European roads favour high-speed cruising at the expense of acceleration and good ride even at the expense of ultimate handling. One cannot expect our two contestants to outrun the British competition in the short term, but over the length of a hard day’s drive it may be another story altogether.

STYLE AND ENGINEERING

To the casual onlooker, the big Citroen looks much the same today as it did when it first appeared 15 years ago. In fact it has had two fairly big facelifts, both at the front end. The first was a few years ago, when it was cleaned up aerodynamically with the addition of a large, smooth undertray beneath the engine compartment. The second was last year, when the new swivelling quartz-halogen headlamps were introduced behind large fairings in a cleaned-up nose.

The Citroen was conceived as a low-drag shape, even though it inevitably meant extra length. A long nose was essential anyway, if a biggish engine and a front- wheel-drive setup were to be accommodated. One of its other major features — the ultra- long wheelbase — found its origins in the earlier front-wheel-drive Citroens dating from 1934. Such a wheelbase brings the promise of a superb ride, but entails problems too, which the French firm endeavoured to overcome with a suspension which to this day is a model of sophistication with its use of aircraft-type oleo-pneumatics and self-levelling (with the handy feature of being able to vary the ride height).

If the first Citroen DS was staggeringly advanced in its shape, suspension and transmission — for the weird semi-automatic, clutchless box was a feature from the very beginning — then that was more than could be said of the engine. This venerable unit came more or less straight out of the old Citroen 15; a strong, reliable, torquey unit with but four cylinders and very undersquare dimensions. It was not smooth, nor was it quiet, and it went ill with the image of the DS as a whole. Eventually it was supplemented, then replaced, by the present oversquare unit: still with only four cylinders, but generally much smoother.

Indeed, this engine with its valves at a 60deg angle on either side of a proper hemispherical head ought to be remembered as one of the last and most advanced of pushrod units before the overhead cam was finally accepted as universal practice.

Just as it might be said of the Citroen, so CAR June 1969 the current Mercedes may look to the untutored eye much as they have done for years past. Put one of the current small-range cars up against its predecessor, however, and it becomes obvious that one is looking at an entirely new car. The ‘new generation’ small cars — of which only the 220 and 250 are sold in this country — represent a very successful exercise in reducing the exterior dimensions of a car while maintaining or even increasing the room inside. Not only that, but the engines are new, and the transmissions carefully matched (say Mercedes) to the characteristics of each power unit.

The basic 220 W115 has a slightly undersquare four-cylinder engine with a single overhead camshaft, and the latest Mercedes four-speed all-synchromesh manual transmission. If you go up one power option and buy the 250 you get (for your £400-odd) a six-cylinder unit of slightly oversquare dimensions producing another 25bhp net and quite a lot more torque. Still, the 220 W115 compares very closely with the Citroen DS although it is marginally upon torque — and this at lower rpm. Mercedes reckon their engines small and hard-worked enough to drag their cars along at respectable speeds without soaking up power with a torque converter. So if you opt for the Mercedes automatic transmission you get their four-speed setup with a simple fluid coupling, very versatile but not giving such smooth changes as the best torque-converter transmissions, nor able to get the car off the mark so fast.

{gallery}DS21{/gallery}

The new Mercedes cars also got a new suspension, notably at the back end. Here the long-established low-pivot swing axle gave way to a very sophisticated semi- trailing arm setup, basically like that in the BMWs or the Triumph 2000 but with great attention paid to its geometry, especially at full rebound.

One of the interesting things about the Citroen is the way it was set up, even in its very earliest days, to use radial-ply tyres; today it runs on Michelin XAs (and the handbook says you should fit nothing else). Mercedes on the other hand have always been very wary of radials. As the good Set right has told us, their suspensions have been good enough to give the right sort of handling without resorting thereto, and they were rightly worried about the possible ride and noise problems. But the great wear bogey has forced them to go to radials, at least for the UK market.

In the brake department Citroen have for a long time used massive inboard discs at the front where most of the weight is, with surprisingly large drums at the rear; the handbrake, as all students of the curious know, acts on the front wheels. Mercedes now use ATE (Dunlop licence) discs all round, again of generous size, with separate drums at the rear for the handbrake to make sure of its effectiveness.

USE OF SPACE

As we have said, the current Mercedes 220 W115 is a smaller car than the old model. But sharing its body shell with a whole range of models which starts with the 200, it is still an impressive enough car at well over 15ft in length. The Citroen DS is a full seven inches longer still, the extra length being accounted for entirely by its extended and drooping snout. A little surprisingly, the French car is no heavier than the Mercedes 220 — although the Mercedes 250 automatic weighs in at rather more than a hundredweight heavier than either of the manual cars.

A look under the Citroen’s long bonnet shows how far back the engine has been pushed, explaining the great bulge in the passenger side of the front bulkhead which covers the back end of the power unit (just as in the Renault 16). All of the transmission lives forward of the engine, with the spare wheel mounted above it. Considering the layout, most of the adjustable or checkable components are surprisingly easy to get at, although there is no light under the bonnet (nor is there in the Mercedes). The last few inches of nose are nothing but space and spare wheel, which may well save the transmission from expensive damage in an otherwise minor shunt.

{gallery}W115{/gallery}

The Mercedes’ square modern shape means that it is better off for space in almost every department. Its radiator, with integral oil cooler, sits squarely at the front of its engine compartment with plenty of space behind it. Once again, real thought seems to have been given to the problems of regular maintenance. The engine is well forward of the front bulkhead, but the transmission naturally intrudes into the passenger compartment.

At the other end of the car the Mercedes naturally has a lot more boot space; but despite the sloping back end, the Citroen is by no means badly off thanks to the depth of boot made possible by the absence of a back axle or a spare wheel.

Looked at in plan, the Citroen tapers sharply towards the rear. But with so long a wheelbase, the back wheels can be taken well to the rear of the passenger space, leaving the back seat an unobstructed width almost as wide as that in front. Even so the Mercedes, despite being the narrower car overall, offers its occupants over six inches more width. The length of the passenger compartment is near enough the same in both cars, allowing plenty of room for back seat passengers even behind a tall driver. Front headroom is no problem, but it is restricted in the back in both cars despite the fact that passengers sit no higher than the driver; the sloping Citroen roofline presents the greater problem.

COMFORT AND SAFETY

Perhaps with memories of the quality of our last two Cars of the Year still firmly in our minds, we found both the Citroen and the Mercedes rather disappointing from the ride point of view, for different reasons.

The ultra-soft, long-stroke ride of the Citroen invites comparison with the NSU Ro80; the latter succeeds better in providing the ultimate in smooth rides without any sign of the heaving, floating feeling which sometimes affects passengers in the French car. Perhaps the answer might be to provide the driver with variable damping — something the DS suspension should lend itself to, and surely no more difficult to provide than the rarely used ability to vary the ride height.

On the other hand the Mercedes ride seems to have suffered from a bias towards handling, and in this respect does not really bear comparison with the Jaguar XJ6. It may well be that those radials have something to do with it; but certainly the Mercedes is in some circumstances disappointingly harsh, and really rough surfaces upset it enough for the handling to get a bit ragged.

At least the Mercedes seats were well tuned to make the most of what the suspension had to offer. Firm, large and well-shaped in the German tradition, their spring rates seemed to have been designed to stay out of phase with the road springs, a feature which brought praise, especially from those in the back. The Citroen seats seemed determined to compound softness with softness, with the result that one sometimes had the impression that the seats were still heaving even when the car had stopped. Nor was their shape so good for locating the occupants, more so when one thinks how much more than the Mercedes the Citroen rolls.

With a wide range of seat movement and a good basic relationship between wheel and pedals, the Mercedes offered drivers of average size and above a really first class, relaxed driving position. Small people may not be quite so well off, both because of the size of the seat and because the pedals get a bit far away; and it is perhaps surprising not to find an adjustable steering column in a car of this class — something which goes for the Citroen as well.

The Citroen front seats have a much more limited range of movement, but the datum can be shifted rearward with the aid of a few minutes’ work with a spanner, after which it should suit more or less everybody and still leave ample room in the back. Steering wheel positions are good in both cars—one soon gets used to the Citroen’s single-spoke affair — and pedal positions are quite acceptable even though those in the French car are forced over to the right by the presence of the engine bulge taking up room in the middle.

Minor controls and instruments are a much more fraught affair in the Citroen, which at times strikes one as being idiosyncratic for the sake of it. Perhaps the most valid criticism is of its handbrake, which is far too far away for a strapped-in driver. Otherwise, most of its more important controls (lights, wipers, washer) are on steering column stalks where they are easy to use once learned.

The Mercedes controls on the other hand are simple and tidy and easily assimilated. A special word of praise is due for the handbrake, a very convenient pull-for-on, twist-to-release handle emerging from the dashboard by the driver’s right hand. Minor criticisms are of the heating and ventilation controls, complicated and lacking in self- explanatory labelling, and a fuel gauge which on our car had a maddeningly vague and wandering needle.

Heating and ventilation was something which had been very well looked after in both cars. The Mercedes system was probably superior (though marred for us by a one-off fault which prevented us from switching off heat at foot level). The Citroen has come a long way from the days when we knew one man who drove an ID and thought the heater wasn’t working when in fact it was; now one gets instant heat, well distributed, and face-level ventilation as well.

The noise problem is very well looked after in these cars until cruising speeds rise above 85mph or so. Up to that point, everything is well under control, more so in the Mercedes which has much the quieter engine at low and medium speeds. Above this critical point the Citroen, whose engine in any case becomes more noisy as speed rises, starts to suffer from fairly spectacular wind noise as the front window glasses, which are frameless, pull away from their seals. The simplest answer if you can stand the drop in temperature is to open the windows fairly wide, for with the Citroen’s good aerodynamics the results are not unduly noisy.

The Mercedes starts to suffer increasingly from a busy-sounding engine as speeds rise towards the 100mph mark, by which time the noise is about as much as a mechanically sympathetic ear can stand. Not that the overall noise level is high, for conversation is still possible. It is just that the engine sounds as though it is working as hard as one ought to expect it to (at least, continuously). The Mercedes suffers from wind noise only to a limited extent, but tyre rumble sometimes intrudes.

Visibility is not bad from either car, but the Mercedes is a much better shape for parking or placing with confidence in a traffic stream, for all four corners of the car are visible; in the Citroen, there is so much that you are very conscious of not being able to see. The Citroen wiper pattern is not bad, even a little limited in area, but the Mercedes uses a clap-hands wiper arrangement which doesn’t greatly appeal to us. Nor does the German car have lights which are really up to its performance; whereas the Citroen’s steerable main beams really do work, and give a truly splendid output. The only worrying thing about driving behind them is the marked reduction in illumination when you have to dip.

PERFORMANCE, HANDLING, BRAKES

These are two biggish cars with relatively small engines; and no matter how efficient those engines, it isn’t fair to expect them to be road-burners. But the Citroen especially is no slouch in manual-gearbox form, now that it has been endowed with a couple of useful power increments. At first sight the Mercedes may seem to offer little performance for the asking price — the times for the 250 automatic we also tried were little better than those of the manual 220, so even with no torque converter there is obviously a fair power loss — but then the most important thing is A to B performance.

When it comes to getting from one place to another along a mixture of A, B and unclassified roads both cars can put up very convincing averages. The Mercedes especially finds little difficulty in averaging 60mph or more, and both make the most of their ability to scuttle along straights at 100mph and go round corners surprisingly quickly. The only thing (apart from the mirror) which one has to watch on English roads is the lack — relatively speaking — of crushing overtaking performance, which means that intelligent planning ahead on the part of the driver can save more time than usual. But the real key to this sort of cross-country performance lies in the reliance which can be placed on the high speed handling and braking of the cars.

Both cars are, of course, high-geared with the object of making high-speed cruising more restful and economical. Economy, however, is a relative thing, and the overall consumptions we obtained were pretty low — with slightly more to be gained by driving the Citroen gently (in other words, by staggering in top gear instead of changing down). Certainly it doesn’t seem that one should expect any great economy bonus by buying a smaller-engined European car in this class rather than a larger-engined British one.

As one would expect, the Citroen has handling which takes a bit of getting used to. The first point is that no matter how much it sways about all over the place on its soft suspension, it makes little difference to the handling and roadholding. The second point is that it remains to some extent a front-wheel-drive car of the old school, and feels about 10 times as safe with power on as it does on a trailing throttle. Not that it does anything really silly if you lift off in mid-corner, although sometimes on a wet road it seems to take its time deciding whether to dive for the inside or break adhesion and go the other way; basically, it is simply incredible what sort of corners it will go round under power, even if over on its beam ends.

In the Mercedes, you can tell at once where the ride has gone; it has gone to make the handling superb. Corners become bends, and L bends curves, and curves you scarcely notice.

It is all very XJ6-like, save that the wet grip is not quite so good not that it matters unduly, with the Mercedes’s excellent balance and superb power steering — and that there is an occasional ill-tempered flick through an 7 S-bend which is certainly attributable to radial sidewall flexure. Indeed, one gets the impression that on really good crossplies the Mercedes might be spectacularly precise and a pleasant to drive, even if slightly more understeer resulted.

Mercedes without power steering, like our basic 220, are precise but definitely on the heavy side. The power steering option on the test 250 is one of the great systems of its kind, so much so that many drivers would never realise the steering was powered. In the Citroen, on the other hand, it is obvious straight away. Here the lightness and the lack of feel make it very easy to apply too much lock, perhaps over-estimating the understeer, with the result that it has to be hauled back untidily. It never feels very pleasant, and when manoeuvring on full lock it can vibrate in a rather upsetting way. When the Citroen was born power-assisted steering for European family cars was in its infancy, and it is obvious that its system has been overtaken by most others.

On an off day on an autobahn or a route nationale you may have to claw your speed down from 100mph half a dozen times in ten minutes. Both the Citroen and the Mercedes recognise this by providing good, strong, fade-proof brakes. The Mercedes ones are very good, eventually locking up all four at something very close to 1g. The Citroen locks up the rears first at something a little below this, but stays very stable under braking for all that, and feels reassuring.

IN CONCLUSION

It is possible that someone in the British market who had decided to go for a foreign quality car would regard the Citroen and the Mercedes as alternatives. But what our driving did was to convince us that they are in fact two very different cars. Both will put up remarkably high cross-country averages. But the Mercedes does it because it handles so well that it is a very easy car to drive fast — to the extent where you don’t even realise you’re doing it — and the Citroen because its adhesion and its front-wheel-drive handling allow it to be really hustled by a driver of reasonable skill who knows the car.

The Citroen is probably the more comfortable in the sort of way in which this kind of driver defines comfort, though the Mercedes may well leave the driver feeling less tired at the end of a long day because it holds mental effort to a minimum.

The Mercedes is expensive, of course. For your money you get the sort of performance we have outlined, along with a restrained exterior and interior in generally impeccable taste (perhaps not ornate enough for some) and superb quality. No Mercedes has any really weak points. On the other hand they may well be accused of lacking character. They will never win firm friends (or implacable enemies) in the same way as the Citroen. To put it another way, one can see our increasingly earnest manufacturers eventually bringing out a car like the Mercedes (the XJ6 might be it, given a few more inches room in the back). But one cannot ever see the British industry doing a Citroen, for better or worse. Now that the old BMC setup has gone the capacity for backing hunches just isn’t there.

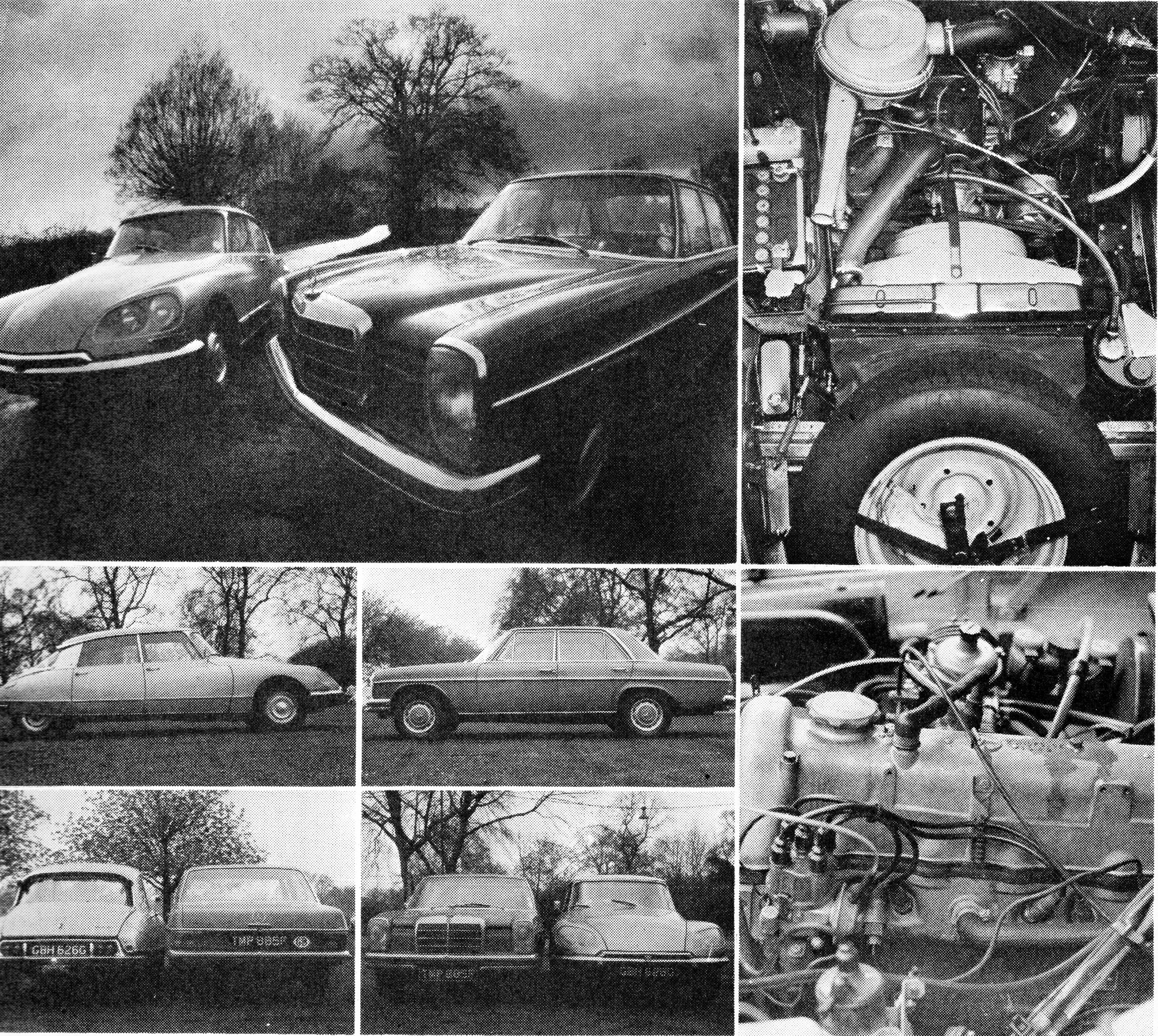

Citroen’s aerodynamic shape contrasts with the Mercedes’ modern boxiness, but length-wise there is little to choose in people space; German car gains a lot in internal width, though. FAR RIGHT Citroen engine appears to hide beneath spare wheel and bits of plumbing, belies accessibility of most important features; Mercedes engine room is spacious and well laid out.

| Car | Mercedes-Benz 220 W115 1969 | Citroen DS21 Pallas 1969 |

| Dimensions | ||

| Wheelbase | 108in | 122.5in |

| Overall width | 69in | 72.2in |

| Front track | 56.5in | 59in |

| Rear track | 57in | 51in |

| Ground clearance (unladen) | 6in | 5-8in |

| Front headroom (seat uncompressed) | 38in | 39in |

| Rear headroom (seat uncompressed) | 34in | 33in |

| Front legroom (seat forward/back) | – | – |

| Overall length | 185in | 192in |

| Overall height (unladen) | 57in | 57in |

| Front shoulder room | – | – |

| Rear shoulder room | – | – |

| Rear legroom (seat forward/back) | – | – |

| Mechanical Specification | ||

| Weight (in lbs kerb) |

2990 | 2850 |

| Steering |

power-assisted recirculating ball |

power-assisted rack and pinion |

| Turning circle |

32ft | 33ft |

| Turns (lock to lock) |

5 | 3.2 |

| Brakes | discs front – Diameter (in) 10.1, drums rear –Diameter (in) 10.1, with servo |

discs front – Diameter (in) 11.75, drums rear – Diameter (in) 10, with servo |

| Engine | ||

| Material | (cylinder head) ligh talloy (block) iron |

(cylinder head) light alloy (block) cast iron |

| Main bearings (number) |

5 | 5 |

| Cooling system |

water | water |

| Valve gear layout | single overhead cam SOHC | pushrod OHV |

| Carburettors/injections |

1 Stromberg 175CDS |

1 Weber 28/36 DLEA1 2175 |

| Compression ratio |

9.0:1 | 8.75:1 |

| Capacity (cc) |

2197 | 2175 |

| Bore (mm) |

87 | 90 |

| Stroke (mm) |

92.4 | 85.5 |

| Power (net bhp/rpm) |

105bhp at 5000rpm | 106bhp at 5500rpm |

| Torque (net lb ft/rpm) |

142lb/ft at 3000rpm | 123lb/ft at 3500rpm |

| Transmission | ||

| Gearbox |

four-speed maual (Mercedes-Benz manufacturer) | four speed all synchromesh (Citroen) |

| Top gear mph per 1000rpm | – | – |

| Ratios: | 1 st 3.90 2nd 2.3 3rd 1.41 4th 1.00 |

1 st 3.25 2nd 1.94 3rd 1.27 4th 0.85 |

| Final drive ratio |

4.08:1 | 4.37:1 |

| Clutch : Make: |

– | – |

| Type |

– | – |

| spring single plate | – | – |

| Wheels and Tyres | ||

| Wheels (type and size) | 14 steel, rim-size 5.5 | 15 steel, rim-size 5.5 |

| Tyres (type and size) | 175HR-14 | 180HR-15 |

| Replenishment & Lubrication | ||

| Type of oil | 10W/40 | 10W/40 |

| Engine sump capacity (pints) | 7 | 9 |

| Engine oil change interval (miles) | 3000 | 3000 |

| Gearbox and final drive capacity (pints) | – | – |

| Type |

– | – |

| Gearbox capacity (pints) | – | – |

| Final drive capacity (pints) |

– | – |

| Type | – | – |

| Lighting | ||

| Number of lights | – | – |

| Type |

– | – |

| Battery (make) | Bosch | Varta |

| Voltage |

12 volt 55 a.h. | 12 volt 75 a.h. |

| Suspension | ||

| Front |

double wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar |

oleo-pneumatic struts, lower wishbones, anti-roll bar |

| Rear |

semi-trailing arms, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar |

oleo-pneumatic struts, trailing arms, anti-roll bar |

| Braking (Actual stopping distance in feet) | ||

| 30mph | – | – |

| 70mph | – | – |

| Fuel consumption | ||

| Overall (mpg) |

18 | 17 |

| Driven carefully (mpg) | 23 | 23 |

| Star rating | 4 | 4 |

| Range |

250-340 miles | 240-325 miles |

| Tank capacity |

14.3 gallons | 14 gallons |

| Performance | ||

| From standstill to mph. in seconds | ||

| 0-30 | 4.0 | 4.2 |

| 0-40 | 6.4 | 6.4 |

| 0-50 | 9.5 | 8.6 |

| 0-60 | 13.2 | 11.6 |

| 0-70 | 18.4 | 16.0 |

| 0-80 | 26.0 | 21.2 |

| 0-90 | 37.9 | 27.9 |

| 0-100 | – | 38.0 |

|

Speeds in gears. From minimum to maximum in each gear. |

||

|

1 |

27mph | 31mph |

| 2 | 46mph | 59mph |

| 3 | 75mph | 82mph |

| 4 | 101mph (max speed in test) | 109mph (max speed in test) |