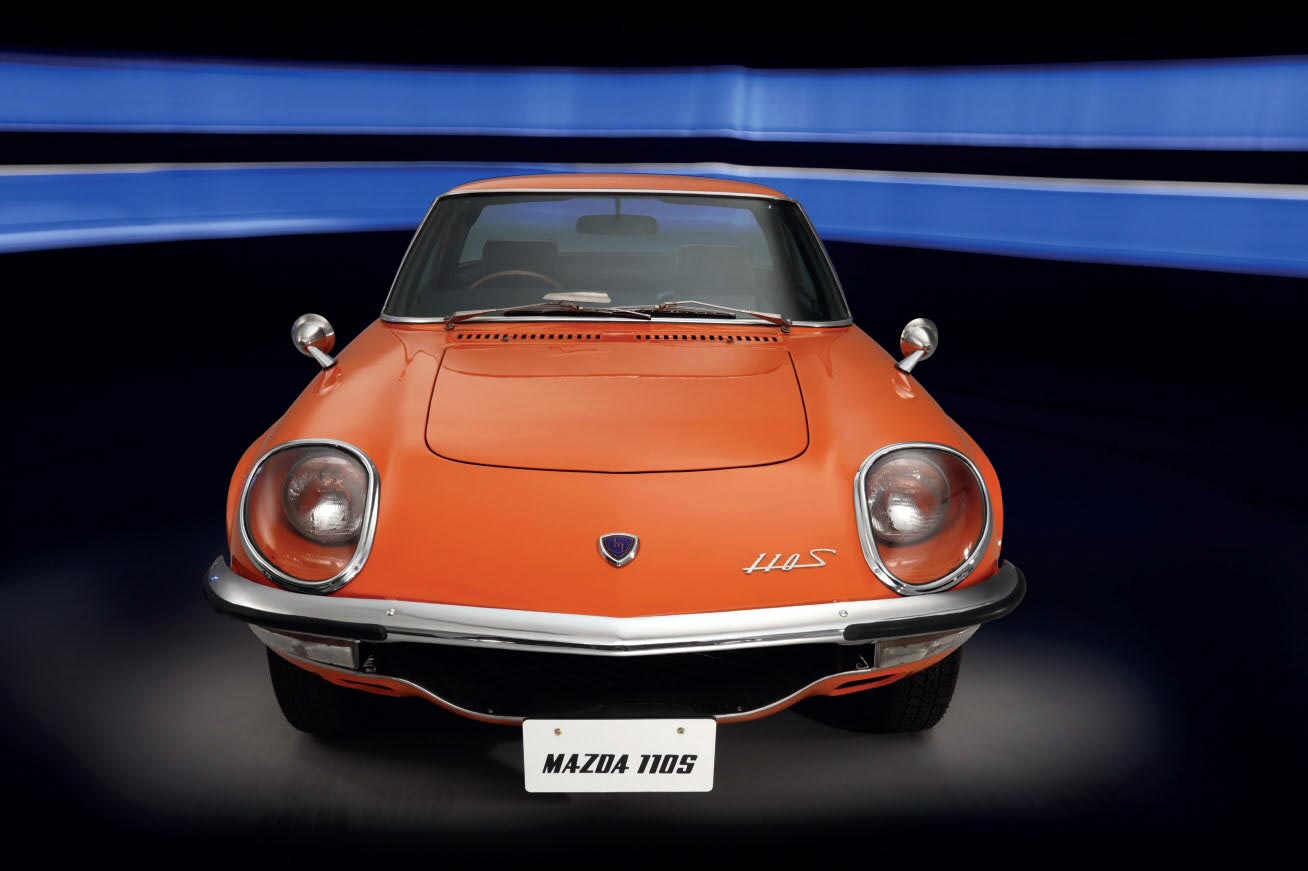

A coupé for the space age. The outrageous Mazda Cosmo proved the Wankel concept. Revolutionary rotary Mazda’s ultra-radical Cosmo coupé. The wild and distinctive Cosmo was the first of Mazda’s celebrated rotaries. James Page tells its story. Photography James Mann/LAT.

This is what’s known as making your mark. Until 1960, Toyo Kogyo had been a manufacturer of three-wheeled trucks, and had made its first tentative forays into the world of cars with two diminutive Kei-class models for the home market. First up was the Mazda R360, which weighed only 380kg and featured a 16bhp V-twin. Then, in 1962, came the four-seater Carol, which was initially powered by a 358cc ‘four’, but which boasted mod-cons such as monocoque construction and all-round independent suspension.

Then it ventured into the world of saloons with the Familia and the Luce. So far, so sensible, but anyone who correctly predicted where the company would go next would have been doing very well indeed. Because where it went next was here: the 110S Cosmo. You have to admire the confidence and vision that must have been necessary to go from Kei-class to sporting GT in only a few short years, especially since Mazda made life even more difficult for itself by deciding upon NSU’s revolutionary rotary engine as a powerplant for its bold venture.

Did it then place this nascent technology in a discreetly styled, low-profile body, along the lines of its Giugiaro-penned saloons? No, it did not. Instead, it went to town with the exterior, too, so that when it was first presented on British shores at the 1967 Motor Show, onlookers were fascinated and startled by it in equal measure. At the time, the radical Cosmo was quite simply unlike anything else on the road or, as Autocar magazine put it in its own understated way,‘ certainly an eyecatcher’.

Where do you start when you’re trying to assess its looks? There are certainly hints of Alfa Spider to the front end, with its cowled headlights that feature little vents to prevent misting, but it gets more extreme the further back you go. The rear is very American in style, with the bumper bisecting the tail-lights, and from that angle the roofline and wraparound screen also evoke any number of US designs.

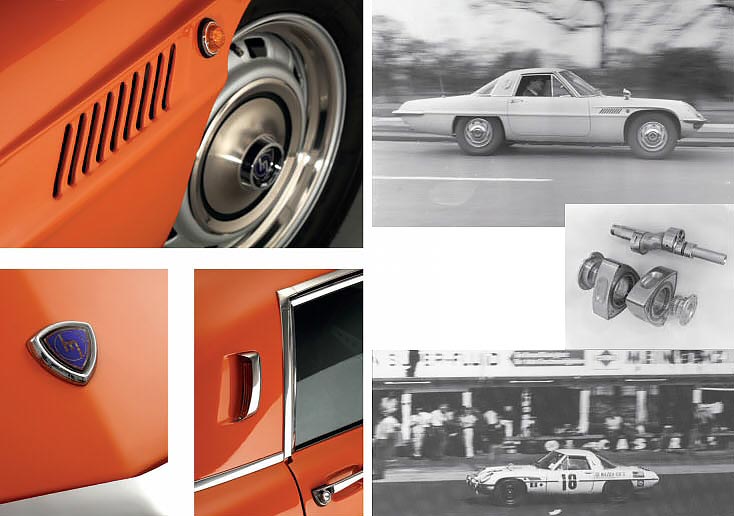

In profile, that rear end appears comically elongated, but your eye is most taken with the prominent swage line that that runs through the centre of the door and forms the top edge of the squared-off rear wheelarch. It’s complemented by another, shorter, line sweeping up and over the front arch to frame the small air vent – a trick borrowed from the Ferrari 400 Superamerica.

It calms down a little inside, with black being the overriding theme. There are lots of neat touches in here, from the dash-mounted map light for the passenger to the integral radio and small pockets in the sides of the seats – ideal, it must be said, for a mobile phone. Even the quarter-lights are pleasing, with push-button operation to release a lever that, when the glass is closed, locates within a recess in the frame.

There’s a stubby gearlever and a broad, wood-rimmed wheel, plus a rev counter that hints at the nature of the Cosmo’s engine due to the fact that it’s redlined at a heady 7000rpm. And, despite the extrovert bodywork, it’s the powerplant, hidden away deep in the engine bay, that generates much of the fascination with this other-worldly Mazda.

Clockwise, from below: show-stopping display at Earls Court, ’1967; rear carries distinct echoes of American designs; engine is well hidden – note twin coils and distributors; 110S referred to car’s power output; slender woodrimmed wheel; Alfa Romeo-style headlamps.

Felix Wankel had started work on his engine before WW2 – his first patent linked to it, in fact, was granted in 1929. That work continued even when he was briefly imprisoned in Germany in 1933, but not until 1951 did he sign the deal with NSU that enabled his design to be developed into a production reality.

In fact, it wasn’t his design that was eventually adopted. Well, not quite. Wankel’s own DKM unit was based around the concept that both the rotor and its housing would rotate – the latter slightly faster than the former. There were numerous problems with this layout, including the fact that the sparkplugs had to spin with the inner rotor and the engine therefore needed to be dismantled if you were to access them. Not ideal for the home mechanic.

That first effort was bench-tested in 1957, but the following year a revised version – the KKM, which was penned by NSU’s Dr Walter Froede – laid the foundation for all subsequent production rotaries. Wankel was apparently not best pleased with the development, but Froede’s far more practical concept was to use a stationary outer casing within which an inner rotor moved in a planetary fashion, so that the chambers could ‘expand’ and ‘contract’ to provide compression. The sparkplugs could be mounted in the casing, where they were stationary and accessible, and porting was vastly improved.

The advantages seemed obvious: no reciprocating parts led to incredible smoothness, and the whole unit was remarkably compact. There were drawbacks, however, mostly involving getting the seals at the tips of the rotor to work effectively and in keeping them lubricated. For the latter, small quantities of oil had to be added to the fuel mixture and burnt with it, which didn’t do much fore missions.

Also, simply getting to that point had taken a hefty chunk of investment, so NSU licensed the design to a number of companies around the world. Citroën and Mercedes were two, and would produce their own cars that used rotary power, but it’s Mazda that has become synonymous with the technology.

Toyo Kogyo signed a deal with NSU in July 1961, only a year after the R360 was introduced, but itsengineers immediately ran intoproblems. Kenichi Yamamoto was the man charged with developing the powerplant for use in a Mazda, but he discovered thatwear on the inner surface ofthehousingwouldeventuallycausetheengine to seize – something thatwould later sound the death knell for NSU’s variant.

But despite almost giving up more than once, Yamamoto and his team started their own development programme in order to make it work. They didn’t quite throw everything away and start again with the concept, but they certainly did more than carry out a little finetuning.

First, they came up with carbon-based seals for the rotor tips, then focused on cooling, oil sealing and the design of the intake ports. Alongside this,work was going on to produce a car in which the new engine – designated the 10A – would be fitted. That process had started at the Hiroshima plant in 1962 via a series of scale models. Some were rather extreme, with huge tailfins, otherswere more sober, but eventually the two elements came together and the Cosmo prototype was shown at the 1964 Tokyo Motor Show. It was fitted with a twin-rotary unit,whichwasonemorethan thatpowering the previous year’s NSU Spider – the world’s first productionWankel-engined car.

Mazda, however, has always referred to its engine as‘rotary’ rather than‘Wankel’, no doubt to emphasise thework thatwent into its version. That thorough preparation didn’t stop after the prototype’s unveiling, either. Before the carwent on sale, the firm organised trials with 60 cars and 1000 members of the public. The president of Mazda himself, Tsuneji Matsuda, drove one from Hiroshima to Tokyo, a distance of some 800km. Mazda had done what NSU couldn’t –madethe rotary reliable.

The Cosmo went on sale in 1967, with its engine producing 110bhp at 7000rpm and 96lb ft at 3500rpm. Each rotor had a capacity of 491cc to give a total of 982cc, and featured twin sparkplugs that were timed 5º apart. Beneath that‘look at me’bodywork was a leaf-sprung de Dion rear axle, with front suspension by coil springs and wishbones. Braking was by discs up front and drums at the rear, while there was rack-and-pinion steering, too.

The gearbox was initially a four-speed unit, upgraded to five for the 128bhp Series II of 1968. The later variant was also stretched by 6in to give a roomier cabin, the engine gained new rotor sealsandtopspeedwasupto120mphfrom 115mph. Each car was handbuilt in Hiroshima, with a total of1519leaving the factory before the model was discontinued in 1972.

In early ’1968, a number of British magazines got their hands on the Cosmo, which, asAutocar admitted, ‘is different from anything we have previously experienced’. Allwere impressed with a car that was offered via the new Mazda Car Sales (UK), based in Newbury, at a cost of £2606. That compared to a Lotus Elan +2 at £2113, an E-type at £2068 and a Porsche 912 at £2676 – and that’s the sort of company in which the Fledging Mazda concern found itself.

The Autocar test went on to praise the‘quick, precise’ steering and ‘impressive’ rear grip. The smoothness of the rotary was singled out, too: ‘When accelerating hard in second and third gears, it is all too easy to sail past 7000rpm without noticing it.’ The seats, meanwhile, were ‘jolly good’, but the heating and ventilation ‘is apparently of the fry or freeze kind’. The magazine recorded a 0-60mph time of 10.2 secs, which, it noted in its data, was faster than both the MGB and Triumph GT6. That said, for the price of a Cosmo you could have bought both of those cars and had roughly £600 left over.

John Bolster tried the Mazda for Autosport: ‘The handling is most unusual because the common fault of most modern designs is certainly not found here. Somany sports cars are marred by too muchweight on the front wheels, but the Mazda has a featherweight engine mounted well back and the result is steering so light as to be disconcerting at first… A potent little sports car of immense technical interest.’

From top: front vent is framed à la Ferrari 400 Superamerica; Mazda badge; chrome strip defines a neat outline around the window; the interior is far more restrained, but features stylish ‘Cosmo’ script and a passenger grab-handle. From top: the Cosmo on test with Autocar, 1968; competing on that year’s Marathon de la Route; rotary internals – note apex seals; Series II has a larger front air intake.

Even Denis Jenkinson, a man not easily impressed, wrote: ‘I could not see that Mazda knew much about sports cars or race-breeding like Porsche or Lotus… I had to change all my pre-conceived ideas… Without doubt it is the Lotus Elan of Japan.’

But while Autocar noted that some British and American designers ‘may live to regret their disinterest in… the Wankel unit’, Bolster sounded a prescient note of caution: ‘It must have a brilliant future ahead of it for every type of car unless it proves more expensive to maintain than a piston engine over an extended mileage.’

In a further attempt to prove the Cosmo’s reliability and raise Mazda’s profile, two were entered in the gruelling 1968 Marathon de la Route. This 82-hour enduro attracted Stirling Moss to the Nürburgring that August to share a Lancia with Innes Ireland and Umberto Maglioli (the gearbox broke while they were leading), but the Mazdas acquitted themselves well against the strong competition. While the Porsche 911 of Herbert Linge, Dieter Glemser and Willi Kausen took victory, the Cosmos looked set for fourth and fifth overall. Shortly before the finish, however, a wheel came off the entry piloted by Yoshimi Katayama, Masami Katakura and Nobuo Koga, and it was heartbreakingly forced to retire. The survivor – driven by Léon Dernier, Yves Deprez and Jean-Pierre Ackermans – continued to finish fourth.

It was unfortunate that NSU never got to grips with its own design in the same way that Mazda did, but while the German company was drowning in warranty claims, the Japanese built on the Cosmo’s foundation to create a famous line of sporting rotaries. First there was the 1970 RX-2, which was followed by the RX-3, RX-4 and the RX-7. TomWalkinshaw developed the latter into a successful racer, winning the Spa 24 Hours in one and overseeingWin Percy’s 1980 and ’81 BTCC successes. Then, in 1991, came theengine’smostfamoussporting achievement, the four-rotor 787B driven by Johnny Herbert, Volker Weidler and Bertrand Gachot claiming overall victory at the LeMans 24 Hours.

There would be other Cosmos, too, once the distinctive original had gone out of production. From 1975-’1981, the name was applied to a more conservatively styled coupéthatwasbasedupon the Luce floorplan and also offered with a conventional inline-four engine. The third generation was a typically angular 1980s effort, and the last Cosmo was the high-tech – think touchscreen controls and inbuilt satnav – Series JC model that lasted until 1996.Most recently in terms ofMazda’s rotary offerings, there was the RX-8, whichwent out of production in 2011.

Despite all the problems in making it reliable, acceptably economical and able to pass increasingly stringent emissions regulations, the rotary survived into the 21st century thanks toMazda’s expertise. During the 1960s, there were many folk who considered the powerplant to be a serious threat to standard reciprocating units, which is why so much interest was shown by so many manufacturers. Even if that didn’t come to pass, it remains an intriguing branch of motoring history, and it found no more fascinating ahomethan the Cosmo.

Thanks to Lucas Hutchings at Fast Classics, which is selling the Mazda: 01483 338903; www.fast-classics.com

‘YOU HAVE TO ADMIRE THE CONFIDENCE AND VISION THAT WENT INTO PRODUCING THIS CAR’

‘THE JAPANESE BUILT ON THE COSMO TO CREATE A FAMOUS LINE OF SPORTING ROTARIES’