Swede Dreams – classic cars for sale. Iconic sports coupé that found fame in The Saint, the Volvo is heavenly if you yearnfor a tough stylish cruiser. Values are soaring for top cars but so are restorationsdue to high cost of body repairs. Less popular ES estate remains the bargain buy.Words and images by Richard Dredge.

THE FACTS GOOD BUY OR GOOD-BYE?

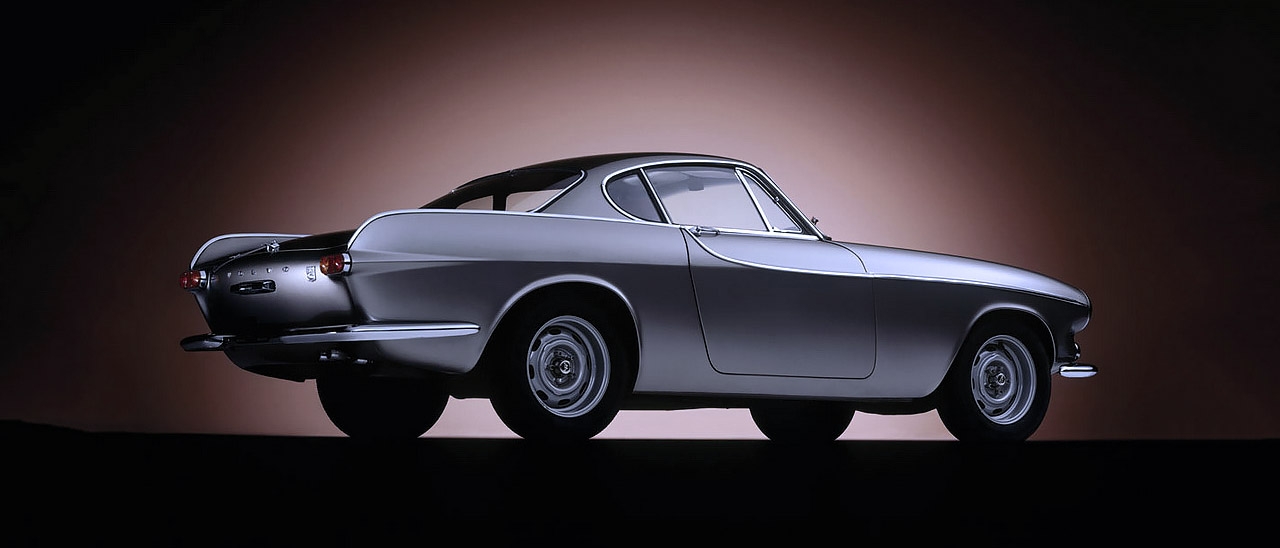

Proof from Sweden that safety and style can mix

Best model? 1967 Volvo 1800S

Worst models? 1965 cars and 1800E

Budget buy? 1800ES

OK for unleaded? Only US-spec 1800E/ES

Will it fit your garage? 4390x1700mm

Spares situation? Generally good apart from ES-specific parts

DIY ease? Excellent

Club support? Excellent

Appreciating asset? Very much so

PREMIUM £77.54 or £94.54 inc Agreed Value

Volvo P1800 52 Year old Male, Living at GL2,

Value £10,000, Garaged, 3000mpa, 2nd Vehicle, clean licence and commuting, Car Club Member 01480 400 905

The engine is simple but super sturdy while even later fuel injected models needn’t arouse fears of home maintenance. A main worry on some cars is the unavailability of brake servo and servo parts so check that the brakes are okay.

There’s something about a classic coupé that just screams style. Usable enough to not be flash, these smart two-door machines were often fitted with relatively prosaic engines so they weren’t wallet-crippling to run, yet they still cut a dash on the street. In the UK, we were spoiled for choice in the sixties and seventies, when it came to affordable coupés – which is why the streets were full of Mantas, Capris and Firenzas. Even Marinas. Before any of these arrived though, there was something equally stylish but just that little bit more unusual, largely because of its higher asking price.

Thanks to its starring role in The Saint, the Volvo 1800 was also something of an icon by the time Ford and GM latched onto the coupé market.

Despite its array of star qualities, the Volvo 1800 didn’t really catch on until very recently. Just two years ago there were bargain 1800 coupés to be had, the market not having realised just what a cracking car this is. But word has now got out and values have climbed sharply – and the chances are, we haven’t reached the top of the market yet.

But while the 1800 coupé has shot up in value, the estate edition that came at the end of production is still far more affordable. Prices for these are increasing too, but you can buy an 1800 sportshatch for half the cost of a coupé – which we’d say makes it something of a bargain.

HISTORY

1960 The Volvo P1800 coupé showcases at the Brussels auto show, but it wouldn’t go on sale until the following year. Volvo has agreed a contract with Jensen to assemble the first cars, with the bodyshells being produced by Pressed Steel in Scotland. Build quality sadly is woeful and as they cost nearly as much as an E-type, they’re not terribly easy to sell. Essentially the car is a rebody of the trusty Amazon saloon but with twin carb power.

1963 Volvo cuts short its contract with Jensen after 6000 cars have been built, and transfers 1800 assembly to Sweden. The car then becomes known as the 1800S (for Sweden) and at the same time the power goes up from 100bhp to 108bhp. The first 2000 of these Swedish-built cars are known as the P1800S though they’re effectively an interim model that features the Jensen bodyshell (complete with natty cow-horn bumpers) but the cars are assembled to a higher standard.

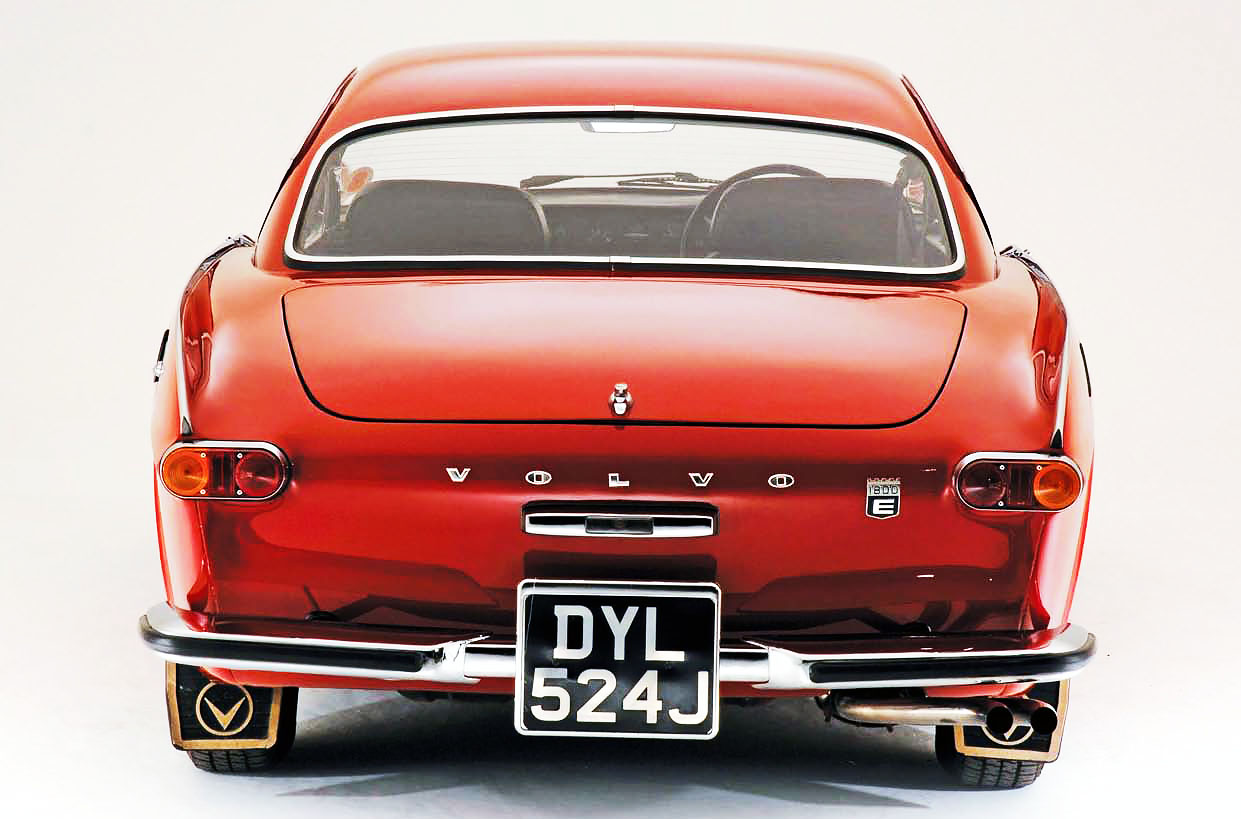

1968 The 1780cc B18 engine is replaced by a larger 1986cc B20 version of the same unit. Dual-circuit brakes are also fitted from this point on as standard. 1969 Bosch fuel injection replaces the previous twin carburettor set up, with a change to 1800E badging – E being short for Einspritz, the German for fuel injection. Disc brakes are also fitted all round to cope with the added perfomance.

1971 A three-speed Borg-Warner automatic gearbox becomes available for the first time. It’s a bit late in the day, but the move reflects the 1800’s popularity in the US, where buyers prefer to have two pedals instead of three. A sports estate, the 1800ES, is introduced with a curious style but added versatility yet it would last just two seasons.

1972 The final 1800 coupé is built in June after 39,407 examples have been made. 1973 The final 1800ES is built, as it isn’t cost-effective to re-engineer this old timer for the American market, where new crash regulations are about to come into force.

DRIVING AND PRESS COMMENTS

Despite the 1800 initially being built in the UK, the first cars were offered only to Swedish buyers and it would take a while for other markets to get their allocation. As a result it took a while for most Englishlanguage magazines to put the 1800 through its paces. One of the first to do so was Sporting Motorist, which tried an early car in its home market.

The magazine was impressed by the 1800’s usability: “The immediate impression on seeing and sitting in the sports Volvo is one of robustness. The roominess is unusual considering the low overall height of the car and even the tallest of passengers can find no complaint on the grounds of leg room. The front seats are extremely comfortable, a quality derived from both the soft padding and the shape”.

If Sporting Motorist seemed keen on the Volvo’s cabin, it liked the driving experience even more: “The 1.78-litre engine makes a splendid job of propelling the biggish car along very quickly. The car was given plenty of opportunity to achieve maximum speed and we found this to be an indicated 170kph (105.6mph), which did not take very long to reach. A little later we tried the car on secondary roads with a great variety of surfaces with slow and fast corners. Here the greatest virtue of the Volvo became apparent: its steering is so positive and direct, the car going exactly where it is pointed. The steering is suitably high-geared yet it is surprisingly light. It is no trouble to negotiate a series of tight bends quickly with such handling”.

Across the pond, Sports Car Graphic was equally gushing about the sporty Volvo. When the P1800 became the P1800S the American magazine gushed: “It is hard to see how the handling of any P1800 could be improved, other than changes made for racing, which will make the car a bit less liveable and the manufacturer has avoided this in the S series”.

By the time Motor tested the fuelinjected 1800, the coupé was starting to lose its appeal. The magazine hadn’t tested an 1800 since 1962, and even then it felt the driving experience was rather old-fashioned; by now it was positively antiquated with its restricted glass area, raised waistline and outdated ergonomics. The extra pep was welcome but the car couldn’t really compete with newer rivals. When it tested the new fuel injected 1800E in 1970 it still considered the coupé dated but “rejuvenated” by the fuel-injected engine but with the car still costing E-type money at £2254 (yet usefully cheaper than the Alfa GTV and Lotus Elan Plus2S) was still an expensive proposition. The small glass area felt dated and was criticised for its poor visibility but praised for its “effortless high speed cruising, writing “more a marathon runner than sprinter”.

In essence, plus the fact they were all launched around the same time, the Volvo feels not unlike an MGB or TR to pilot but “with an outstanding ride” reckoned Motor. The 1800’s last gasp was the ES, and if there was a car that polarised opinions in period, this was it. Autocar reckoned its ergonomics were outdated, the cabin was cramped and refinement was nothing like competitive enough – although the build quality was good and it looked rather smart.

PRICES

Kevin Price is well known in Volvo circles; not only did he set up the Volvo Enthusiasts’ Club back in 1989, but he also owns a multitude of 1800s. Among these is a unique estate conversion (see separate panel) along with 71 DXC – otherwise known as The Saint Car (www. thesaintvolvo.co.uk), as it originally appeared in the iconic TV programme alongside Roger Moore.

Says Price: “At the moment 1800 values are all over the place, with coupés going up constantly but estates far less sought after – when it was new, the estate sold relatively well in the UK. You can buy an 1800ES for around half the cost of an equivalent coupé”.

There used to be a lot of suspicion around the fuel-injected cars, because it was assumed they’d be difficult to keep running properly. Now, any coupé is sought after although there’s still a definite pecking order. Particularly desirable are the earliest 1800s with the cow-horn bumpers (the P1800 and P1800S). But with just 50 or so of these cars in the UK, including scrappers, there aren’t many to go round. Find a Jensen-built car and you’ll pay £7000 for a complete heap, while something really nice will fetch £30,000; 18 months ago the best cars were worth £20,000, says Price. You’re unlikely to find a P1800S, as few were made and very few survive in the UK. If you’re lucky enough to find one, values are the same as for the Jensen-built cars.

Next came the 1800S, which was the first car to be built with the re-engineered bodyshell, although the first year of production still featured cowhorn bumpers. The 1800 built from 1965 on (with flat bumpers and slotted wheels) are the most common of all the 1800 derivatives so it’s the one you’re most likely to find. You can pick up something worth owning for little more than £10,000, but if you want something really nice you’ll have to increase your budget to more like £20,000.

The next edition was the 2.0-litre 1800S, which is another rarity as it wasn’t built for long, which is why values are high. This has a bigger engine than any 1800 made up to this point – so it’s perkier – but it’s still got most of the charm of the others. The final coupé was the 1800E, with its fuel-injected 2.0-litre engine. These are at the more affordable end of the spectrum, even though they’re rare because the 1800E was built for just three years. Values are somewhere between those for the 1800S 1.8 and the earlier models, so you can expect to pay over £20,000 for something really nice.

If that’s too rich for you, maybe it’s worth setting your sights on an 1800ES instead. Likely to always be the poor relation, this 1800 shooting brake still cuts a dash but those lower values mean owners are less inclined to spend money on these more practical 1800s – so you’re going to find it that much harder to find something really good. Ropey cars start at just £6000 and if you can find something really nice you’ll pay up to £15,000.

Says Price: “The cars to avoid are those built in 1965, when Volvo started to cut costs. For example, instead of stainless steel trim there was anodised aluminium and a cheaply made flat grille. These cars were the first to get flat bumpers in place of the previous cow-horn items – but as the 1965 1800 is also quite rare, the chances are that the first good one you find will be from another year of production”.

IMPROVEMENTS

The 1800 is very usable in standard form if set up properly, but there are some worthwhile upgrades to consider if you plan to use the car a lot. Halogen lights are recommended (at less than £50) along with an alternator conversion if it’s an early car, although the standard-fit Bosch high-output dynamo is reliable.

The brakes are good so don’t really need any modifications, but such improvements might be necessary if you fancy putting a pokier engine in the nose. Swapping an 1800 unit for a 2-litre one is easy as it’s a straight swap – traditional tuning methods can also be used to coax more horses from either powerplant and remember the engine was enlarged in the 140 and 240 ranges and we’ve heard of some cars fitted with units taken from the much later 850.

Period tuning gear is around, look for Ruddspeed but there again, it’s just as cool to play Simon Templar with a standard car!

The steering is inherently heavy; if it’s too much for you then consider an EZ electric power steering conversion which is said to work well. Talking of comfort, it can also be worth fitting 1800ES seats into the coupé as they’re more comfortable on long-distance journeys with their integral headrests.

VERDICT

There were probably more variations on the 1800 than you realised, yet add them all up and the total production run for all of them is a mere 47,000 or so units over more than a decade.

Many of those cars have long since rotted away, so the 1800 is probably a lot rarer than you thought. With excellent usability, lashings of style and a much better driving experience than Volvo’s reputation might have you believe, the 1800 is one of the most usable classics you can buy.

In 1800ES estate form it’s especially usable, and as this is by far the most affordable of the breed, we’d say it’s also the one to seek out – whether or not you’re on a budget.

THREE OF A KIND

FORD CAPRI

A true cult car that’s increased in value massively in recent years but still value in Mk2 form. These cars have well and truly emerged from their banger status, with all editions now prized, but mostly Mk1 and V6 Mk3 cars. Easy to tune but capable of rotting for England, the Capri is great fun but it’s easy to get your fingers burned. Like the Volvo the Ford is simple uncomplicated fun and spares and repairs are easy.

FIAT 124 COUPÉ

A car that lived in the shadows of its more expensive Latin relation, the iconic Alfa GTV, but the Fiat was just as sophisticated with its sparky twin cam engines and five-speed transmissions – indeed some reckon is was equally as good. Prices remain pretty keen with a good example costing around £5000 with a top car well under ten grand but spares can be scarce and they rot badly. Get a good one and you’ll love it though.

RELIANT SCIMITAR GTE

A rival for the 1800ES rather than the coupé (although Reliant also made a Scimitar fastback before the GTE. The later sportshatch is one of those cars that makes sense on all levels. Not only is it swift and good to drive, but it’s also well-served by specialists plus it’s eminently practical too. Even better, the cars are easy to work on and durable; who could want for more? Dirt cheap for what they offer, strangely.

1800E used these nice alloy wheels although thanks to The Saint, you see lots of cars running on Minilite ones Brightwork is of good quality and generally lasts the distance, unlike body panels which are mega expensive.

Overdrive was standard and as good as a five-speed, strangely no auto option. Generally reliable and silent.

Electrics can be troublesome, especially the Lucas parts. For 1968 all used alternator; earlier cars may be converted.

Despite being 55 years old the coupé body still looks the business.

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

GENERAL

Trim is scarce, dashboards crack if left in the sun; repairs are impossible and replacements are unavailable. All had leather-trimmed seats and the seams split; a retrim is around £500. Trim panels are available, at £250 for a set of door panels.

Exterior trim is easy to find, but can be expensive. The grille surround is prone to accident damage, with replacements £300. But the brightwork lasts well. Early cars featured chrome-on-brass brightwork that’s of excellent quality so it can easily be rechromed.

Until 1968 all had a dynamo; after that an alternator was fitted. All external electricals are Lucas while everything underneath is Bosch. The Bosch units are reliable but Lucas parts suffer from corroded contacts; most issues can be traced to problematic Lucas fuseboxes – (there’s a separate unit for overdrive protection), on the nearside wing.

Switchgear is reliable apart from the dimmer switch for the panel lighting, it’s easy enough to just wire it into the main circuit.

The 1800ES also features an interior with imitation plastic wood trim, which many people don’t like. As a result some cars have had their dashboards changed to the earlier design.

HYDRAULICS

The lifespan of an 1800 gearbox is comparable to the average artic – at 100,000 miles it’s nicely run in and is all set for hundreds of thousands more miles. That means keeping it topped up with oil, to make sure the bearings don’t get starved of lubricant. n If the oil level isn’t up to the mark, there will also be problems with the overdrive, fitted to all UK-market cars. The only other likely source of overdrive problems is the electrics, with the same type of problems that afflict any overdrive-equipped car – poor earths, trapped wires, failed relays and a problematic fusebox on the inner wing.

If the steering is really heavy it’s because the steering box has been overtightened to remove any play, and the result will be a damaged box when it wears prematurely. Hopefully the damage won’t have been done yet, and by slackening it off it’ll be sorted, but if it’s too late you could have problems finding a replacement steering box as they’re not available except as second hand units.

The suspension is tough, apart from the four top wishbone bushes. They wear out but replacing them is easy and they cost all of two quid a shot. Alternatively you could opt for polyurethane items, but they’re not normally recommended because they reduce the refinement levels a bit – although they are more durable.

If you’re a slave to originality and you want one of the earliest (Jensen-built) cars, make sure the proper wheel trims are in place; if they’re missing you’re unlikely to find replacements. Even if the covers are there, they’ll be tatty as they tend to fly into the scenery, so don’t expect perfection. Kevin Price recommends running your car with the later ‘red hub caps’ which are easily available new, and keeping your Jensen trims (worth around £200 each if you can find them) for shows.

Post-1970 wheels had an alloy hub and a steel rim, and after a while they separate. Few 1800s have these original wheels; your best bet is to source a set of wheels from a 140-series Volvo, which go straight on.

ENGINE

Whichever unit is fitted there shouldn’t be any problems unless it’s done over 200,000 miles – these powerplants really are that durable. Check that the oil has been changed every 6000 miles.

A car that’s been well looked after will also have a genuine Volvo oil filter fitted, complete with non-return valve, available through the Volvo Enthusiasts’ Club. Cheaper makes don’t have this and as a result the bearings will be starved of oil when starting from cold.

But if at cruising speed there’s a thump that sounds like the big end bearings have gone, don’t fret as it’s much more likely to be worn timing gears, which will still cost you £200 to fix, split equally between parts and labour.

As long as there’s 40lbft on the clock when the engine has settled down to a warm idle, the engine should be in fine form – even better if it displays 50-55lbft once cruising. Although the engines aren’t that parsimonious, if you find yourself putting in petrol at a wallet-crippling rate it’s probably because the thermostat needs replacing, and the engine is running too cool. Fit an 82 degrees item for modern driving.

While the fuel injection system isn’t inherently unreliable, if it’s running badly it could cost a lot of money to fix. A fuel pump costs £200 and there are four injectors at £100 apiece – and that’s just for starters, which is why many have been converted back to run on reliable old SU carbs.

BODY AND CHASSIS

Rust can be a major problem, with replacement panels largely unavailable; when they do crop up they’re costly. The inner and outer front wings are especially rot-prone, so look inside the wheelarch towards the top of the wing. Repairs cost around £1500 for each side. To do the job properly the windscreen has to be removed.

The front panels are the ones most likely to rust, particularly headlamp and sidelight surrounds, front wheelarch lips and sills. Genuine front panels are no longer available but hand-made ones are available for around £1200 or you can buy repair panels for around the headlights. Repro sills don’t feature the correct curvature. Look for a series of vertical grooves below the door.

The front crossmember rots. It’s a four-sided box section, the front of which (behind the valance) can rust away while the rest looks fine and the car passes its MoT. Patching it up properly is a real pain because it’s welded all the way round and accessibility is nil with the engine and its ancillaries in place.

The steering box mountings and front outriggers rust too. If the outriggers have gone it’s possible to buy Volvo replacements, which are the best ones to go for at £35 each. If the steering box mounting has rotted it’s more serious, because this is a chassis leg. MoT pass will cost £400 or so. The rear outriggers (underneath front seats) need check.

There are plenty more areas that can give problems, such as the fuel filler bowl surround, bootlid rear edge, the bonnet around the hinges, floorpans and the bottoms of the doors. Another area that can fill up with water is the floorpans.

1800 RARITIES

Along the way there have been all sorts of unusual 1800s, including a raft of convertibles built by an array of companies. As well as several home-built conversions, Volvoville in the US converted about 50 cars, all with left-hand drive. There’s one in Belgium and none are known of in the UK – the rest are in the US.

Radford also built a pair of 1800 drop-tops, one of which survives. It was put up for sale last year but it wasn’t really priced to sell considering it needs a complete restoration, so it failed to change hands.

The most intriguing 1800 conversion though is the estate that’s owned by Kevin Price – although it’s currently up for sale. He’s owned it for 17 years and it was in a sorry state when he acquired it. It’s even worse now, having been stored outside for many years – it really does need a lot of TLC. The estate’s history isn’t known, including who converted it into a shooting brake, but Kevin thinks it may be an Abbotts of Farnham production. So if you’ve got any idea or you fancy taking on this rather daunting project, get in touch with Kevin via his website: www.thesaintvolvo.co.uk.