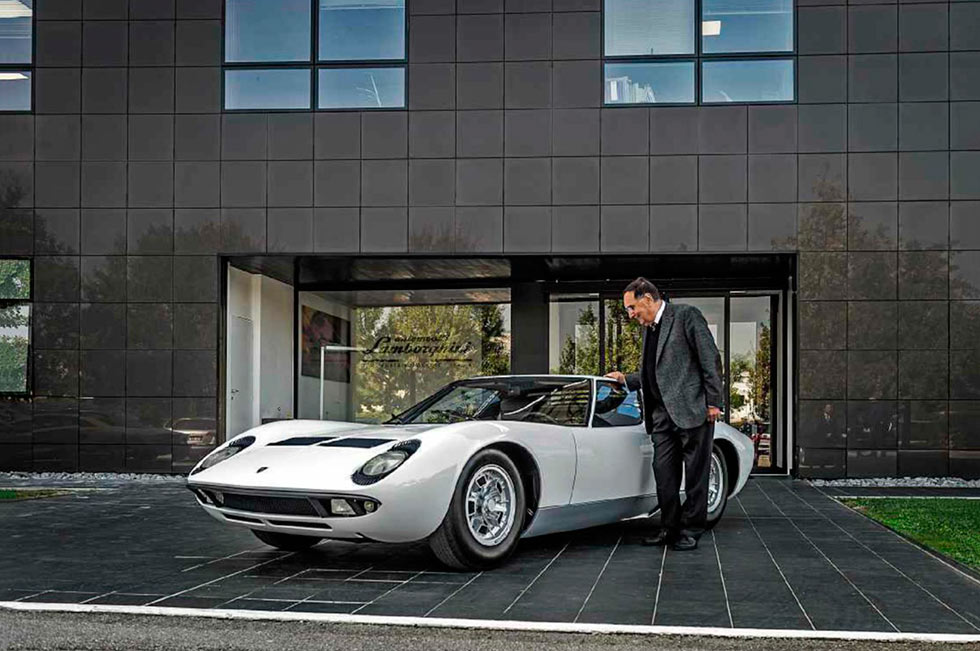

Exclusive! Gian Paolo Dallara’s own Miura. Happy Birthday , Gian Paolo… Dallara’s Miura. Gian Paolo Dallara was one of the fathers of the Lamborghini Miura. Finally, he’s treated himself to one – for his 80th birthday. Words Massimo Delbò. Photography Max Serra.

DALLARA’S OWN MIURA He designed the chassis, now he owns one

Do you remember your last birthday present? If not, maybe it wasn’t such a special one. But the present that race-car engineer and former Lamborghini chief engineer Gian Paolo Dallara bought himself for his 80th birthday would be extremely difficult to forget: a 1967 Lamborghini Miura P400.

We’d say he’s earned it. Dallara is probably responsible for more motor sport success than any other human on the planet. There isn’t a weekend goes by in which something with a technical contribution made by his company is not racing – and winning. Originally from a small village in the Italian district of Parma, in the northern part of Emilia Romagna, young Gian Paolo always loved cars. His mind was imprinted by them passing by on the Mille Miglia, yet he had dreams of becoming an aeronautical engineer. And that’s why, in the mid-1950s, he moved to Milan to attend the Politecnico, where a certain Enzo Ferrari was testing the engines of his racing cars.

When Ferrari asked for a talented young engineer, the recently graduated Dallara was the first name on his list. It was obviously the opportunity of a lifetime.

‘I entered Ufficio Tecnico at Ferrari in 1959,’ he recalls. ‘Carlo Chiti was my boss, one of the few who was very good at both engine and chassis design, and colleagues included Franco Rocchi, still one of the best engine specialists, and Walter Salvarani, who was in charge of the chassis. They were both from the Officine Reggiane, back then the technical heaven for every engineer. From them it was possible to learn every day.

The company was still small enough that Enzo Ferrari himself welcomed me on my first day at work, and there was time for me to look around at the whole process of imagining, designing and building a car.’

He seldom left his office. During a period spent calculating structures, or drafting gears and suspension, the highlight of his working day was to see drivers coming to test the seats for their new racing cars. So Dallara left Ferrari for Maserati in 1962. ‘I simply wanted to go out on the track, to become more active,’ he recalls. ‘Maserati did not have a racing department, but maybe because of that I was allowed on the racetrack. I remember the first time: I was 25, at the 1962 12 Hours of Sebring. We finished fifth with Roger Penske and Bruce McLaren. And the transcontinental flight on a DC6 with a piston engine… it was like taking off to Mars, and that was what I was looking for.’

It was in 1963, while he was working on Maserati’s Lucas mechanical fuel injection, that car enthusiast and friend Corrado Carpeggiani linked Dallara with Ferruccio Lamborghini. ‘He told me of his project and I joined the team,’ says Dallara, who was employed as an external consultant to work with Giotto Bizzarrini, trying to extract as much power as possible from his 3.5-litre V12 engine, along with two young talents from Ferrari and Abarth, Achille Bevini and Oliviero Pedrazzi. Some months later, Paolo Stanzani, who became a lifelong friend, joined too and together they became the foundation of Automobili Lamborghini.

‘Looking back at those days, I’m increasingly convinced that only a new man in the car business, as Lamborghini was, could have hired somebody so young and unaware of how much he still had to learn as me.’ At Lamborghini everything was new, and most of the time whatever was required was simply designed and manufactured in-house by the very young, passionate and sometimes conceited team, supported at all times by Ferruccio’s motto: ‘If we don’t experiment, we can’t create something new.’

Such innovation creates amazing, futuristic products, including the double-overhead-cam technology of Lamborghini’s first car, the 350 GT, a sophistication that even Ferrari was yet to apply to its road cars. But it also comes at a cost, in reliability and development time, with the early customers having the privilege of being the development drivers. And only three years after the first Lamborghini, the Miura arrived, a car that forced the car world to invent a new term to define it: supercar.

‘The idea for the mid-mounted transverse engine location in the Miura came to the Lamborghini team while looking at the Mini, the genius invention of Sir Alec Issigonis,’ says Dallara. ‘He’d employed the transverse-engine concept to save space in his revolutionary, tiny car; Lamborghini simply moved the engine further back to allow for a mid-mounted V12 without a long wheelbase. Everything else was a consequence of this idea, and the Mini heritage can be seen in the first sketches by Pedrazzi.’

When Lamborghini showed its first rolling chassis at the Salone dell’Auto di Torino in November 1965, they really had no idea who would clothe it. Every decision was taken on the spot, and a fundamental move towards turning the chassis into a car came with an improvised meeting between Nuccio Bertone and Ferruccio Lamborghini. Even today, Dallara remembers that his team rather liked the Ford GT40 and wondered if something similar could be created.

‘It was around Christmas, it was snowing and the company was closed for the holiday. I remember driving to Sant’Agata for a meeting with Ferruccio, Bertone and Enzo Prearo [Bertone’s commercial manager], to see the first proposal for the car. As soon as we saw it, we fell in love and we asked Bertone not to touch it any more. It was simply perfect. When Lamborghini saw the car, he said “I like it, with this we’ll enter history, but we won’t be able to sell it.” Yet both he and Bertone forecast a 50-strong production run over five years.’

The result starred at the 1966 Geneva show. A few days later, it was driven to Monaco, during the Grand Prix, and the rest is now a legend.

This 1967 MIura P400, chassis no 3165, the 68th built and still with the extra-thin 0.8mm chassis tubing, was originally delivered on 10 October 1967, through the Parma Lamborghini dealer Mariano to Pier Luigi Bormioli. He was the son of an Italian glass magnate, an ardent playboy and the personification of the best days of the Italian Dolce Vita.

The white-on-black P400 soon became well-known in Parma and throughout Italy, because it was often used by his mistress, starlet Tamara Baroni, one of the most beautiful girls to grace the covers of the gossip magazines of the period.

‘I remember the car very well,’ says Dallara, ‘since the day Mr Bormioli came to Sant’Agata Bolognese to collect it. I later saw it, already nicknamed “the Tamiura” by the gossip press, during a weekend I spent in Parma. It was always parked in front of the most exclusive places, but the idea that I might one day have the money to buy a car of that sort was so remote that I never thought about it. Back then, since the early 1960s I’d been the proud second owner of a light blue Fiat 500, bought at the Lombatti Fiat dealer in Fornovo as my only means of transport. I drove it every weekend from Maranello to Parma and back.’

Only in the last 15 or 20 years did Dallara start toying with the idea of buying a Miura. However, again and again, the time it took for him to convince himself he should allocate the budget for it meant that the car had already gone up in value.

‘But as I approached my 80th birthday I pulled the trigger,’ he says. ‘It’s now or never, I told myself, and I bought the cheapest available car, a 400 offered for sale in Sweden, painted grey and not in very good shape. I was totally unaware that it was the Bormioli car, originally delivered in my birth city. I later discovered that the less you spend in purchase, the more you spend in restoration, but luckily I found the people at Lamborghini Polo Storico were happy to help me, and taught me how a good restoration needed to be done.

‘I spent evenings with my daughter imagining the right colour to paint the car, until Polo Storico’s guy told me that the only correct option was to respect the original white, and he convinced me. The only nonoriginal part I’ve been allowed is the leather that covers the doors, instead of the original Vipla.’

The restoration took 14 months, about 3000 manhours, and every single component of the car has been restored, if original, or replaced when not. Great attention has been paid to details, even the very smallest, to make it as close as possible to when it was delivered to that first customer. And when a very excited Dallara arrives in Sant’Agata on a sunny Italian autumn day to collect the finished project, we are there waiting for him.

‘I haven’t seen the finished car in the metal until now,’ he says. ‘So far I’ve only seen some pictures of it, published after it won the Best in Show trophy at the Salon Privé concours. I got an incredible number of phone calls congratulating me for that trophy, far more than when my cars won Daytona. I wonder if I’m still capable of driving it; the last one I drove was more than 30 years ago.’

But as soon as Paolo Gabrielli, director of after-sales at Polo Storico, hands Dallara the keys, he proves himself still more than capable of handling the Miura. ‘Today’s traffic is not the best environment for such a car. For me it will be not a big issue – so far I’ve planned just a single journey in it, to Locanda Lorena on the island of Palmaria, to eat fish with my granddaughter.

Then I’ll show the Miura to the young engineers working for Dallara, to show them how naïve we were, and how, back then, electricity was only needed for the distributor, a detail we had to modify because the Miura engine was running anti-clockwise.

‘I’ll make them laugh when I tell them how Ford’s R&D department bought one and sent us a picture, showing how, during their test, the metal bar linking the suspension bent. I’ll show them how we built one of the most amazing cars in history while making so many mistakes with safety – or the lack of it; putting too much weight over the back, and using four tyres of the same size. The cooling fans were too weak, and we didn’t know we should have closed the area beneath them to improve their effectiveness, and we did an inhouse gearbox and differential, because we needed it to make the car, without considering that none of us had ever designed one before.’

In 1969 Dallara left Lamborghini to go racing, and he started working with Frank Williams and Alejandro de Tomaso for their Formula 1 team. In 1972 he established his own firm, in the garage behind his father’s house, to save every possible extra expense, while still working for Lancia so he could earn a salary for his family. Yet despite his personal successes since, Dallara’s love for the Miura and for his time at Lamborghini are very evident.

‘We were all young, making our dreams come true; and even if I could imagine that without the Miura my career would have been the same, I’m proud to be considered one of its fathers and I have fond memories of the people I met during those amazing years.’ In saying so, he looks at the production sheet of his own car, immediately recognising the handwriting and signature of the late test driver Bob Wallace, and asks for a copy of it just before agreeing that we should take his freshly restored Miura to the late Paolo Stanzani’s house for photography. ‘It is a wonderful idea,’ says Dallara. ‘I can’t imagine a better way to celebrate a great partner in work and a friend in life than by showing him my birthday present.’

TECHNICAL DATA FILE SPECIFICATIONS 1967 Lamborghini Miura P400

Engine 3929cc V12, DOHC per bank, four Weber triplechoke downdraught carburetors

Power 350bhp @ 7000rpm / SAE

Torque 262lb ft @ 5000rpm / SAE

Transmission Five-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

Steering Rack and pinion

Suspension Front and rear: double wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar

Brakes All Discs

Weight 1125kg

Top speed 163mph

0-60mph 6.3sec

{module Lamborghini Miura}

‘as I approached My 80th birthday I pulled the trigger. It’s now or never’

‘I REMEMBER DRIVING TO SANT’AGATA FOR A MEETING WITH FERRUCCIO, BERTONE AND ENZO PREARO TO SEE THE FIRST PROPOSAL’

Dallara’s greatest hits

Here’s some I made earlier. Gian Paolo Dallara could be Italy’s best-kept racing secret. Here’s why… Words Richard Heseltine.

You could say that Gian Paolo Dallara owns motor racing, but somehow that description seems wholly insufficient. With most modern-day categories being one-make series, Dallara builds cars for every major championship on the planet, from Formula 3 to IndyCar via all things in-between. And by that, we mean all the cars. Then you have to factor in his behind-the-scenes contributions to some of the greatest sports-prototypes of the past two decades (think Audi). Save for Formula 1, there are few arenas of motor racing that he hasn’t conquered.

All of which is lightyears removed from when he started out at Ferrari in 1959 as an aeronautical engineering graduate. Dallara subsequently jumped ship to Maserati and then Lamborghini, where he initially worked on developing the 350GT’s chassis and gearbox. He was also tasked with turning Giotto Bizzarrini’s V12 engine design into something fit for a roadgoing gran turismo.

He lent his engineering skills to a raft of other models during the 1960s before designing a Formula 2 car for Alessandro de Tomaso. This in turn led to a position as technical director. That, and a Formula 1 bid with the Frank Williams-run 505 in 1970. Dallara also designed the chassis for the Pantera supercar before moving on to assist with the development of the Lancia Stratos.

After establishing Dallara Automobili in 1972, the designer also became a businessman – and a shrewd one at that. Constructing sports-racers for the local market brought in much-needed lire. The small factory in Varano de’ Melegari near Parma soon became a hive of activity, while Dallara continued to act as a consultant to mainstream manufacturers.

During the 1970s, he developed the Fiat X1/9 Group 5 racer that inspired Lancia’s competition chief Cesare Fiorio to commission the construction of the Beta Montecarlo Group 5 car – which claimed the 1980 World Championship for Makes. It marked the first international title for a Dallara-designed car and spawned the LC1 Group 6 car and LC2 Group C weapon. Scroll forward to 1994, and Dallara’s firm was given the job of designing what became the Ferrari 333SP. That’s the very sports-prototype that claimed 56 wins into the following decade.

The 333SP was primarily targeted at the US, and it was via client/racer Andy Evans that Dallara was granted an entrée to Indy principal, Tony George, in the mid- ’90s. Champ Car racing was in the midst of a controversial split, and George commissioned the construction of 15 new Dallara single-seaters for the new IRL breakaway series, plus 15 from rival constructor G-Force. Eddie Cheever won the Indy 500 in 1998, which marked the first victory for an Italian marque at this legendary venue for 58 years.

Dallara wasn’t done with road cars, though. Over the past two decades, his firm has played a role in the creation of everything from the KTM X-Bow to the Bugatti Veyron via the Maserati MC12 and the Alfa Romeo 8C. The football-obsessed engineering great shows no sign of slowing down, either. We would be disappointed were it otherwise.