Prestige compact – 1967 Jaguar 420 road test, the worse the conditions, the more conspicuous its virtues become.

By any sort of overall scale the Jaguar 420, at £2,100, is little more than a medium-priced car. Yet it seems somehow insolent to apply medium standards to a saloon that for a combination of speed, comfort and safety is as good as any in the world, regardless of cost. Even with the rather jerky automatic transmission fitted as an option to our test car, its quiet, fussless performance is still formidable if no longer quite so fierce and smooth as some competitive American V-8 saloons. But the 420 lives in a different world of stability and the worse the conditions, the more conspicuous its virtues become. You can drive at maximum speed — approaching 120mph — in pouring rain without in any way alarming yourself or your passengers, a situation in which some other fast cars would feel far from reassuring.

Despite its performance and E-type pedigree — which rubs off as outstanding roadholding even on bad roads — this is not a car with any strong sporting pretensions, as the wide, slippery seats will reveal on a twisty road. Similarly, the power-assisted steering (another option) is likely to attract more praise for its lightness and stability than criticism of its poor feel when cornering near the limit. As a Grand Tourer — far more grandiose, in fact, than many so-called GT cars — the 420 is superb and at its impressive best on a long-distance journey when it win carry four adults of medium height in great comfort, with room to stow all their luggage in a big boot. With a full complement of six footers there has to be some negotiation over the allocation of legroom.

| Jaguar |

3.4 Mk. 2 |

3.8 S-type |

4.2 420 |

4.2 420G (MkX) |

|

Max speed |

119.9mph |

116.0mph |

115.0mph |

118.2mph |

|

0—50mph |

9.0 sec | 8.5 sec | 7.0 sec |

8.0 sec |

|

0—100mph |

33.3 sec |

34.3 sec |

29.8 sec |

29.8 sec |

|

30—50mph |

4.6 sec |

4.0 sec |

3.5 sec |

3.7 sec |

|

50—70mph |

6.3 sec |

8.0 sec |

5.3 sec |

4.9 sec |

|

70—90mph |

10.7 sec |

10.1 sec |

9.3 sec |

9.5 sec |

|

Weight |

30.2 cwt | 33.2 cwt | 33.3 cwt |

37.5 cwt |

In many ways, of course, the 420 is very similar to the slightly less expensive S-type on which it is based. What it does — and does very effectively — is to provide 420G (ex-Mk X) appearance, prestige and performance in a smaller, cheaper car, a package we ourselves think more appealing and practical if you are prepared to sacrifice a little accommodation. The 420 gives virtually nothing else away. As in all Jaguars the interior remains as traditionally old- fashioned as a staid Mayfair Club. It is very nearly as peaceful, too, though there are those among us who look forward to the time when Jaguar abandon tradition and employ their talented designers to produce a really modern, ergonomic interior layout. But this is a matter of personal taste.

Performance and economy

The Jaguar 420 uses a special two-carburetter version of the 4.2-litre engine, giving 245bhp against the 265bhp of the Jaguar E-type and Jaguar 420G on three carburetters. Thus the 420 bridges both the price and power gaps between the 3.8-litre, 220bhp S-type and the 420G. However, as a general rule, weight also increases with price and power in the Jaguar saloon range so that performance does not vary all that much among the top automatics, as the following table shows.

The Jaguar 420 has a useful edge over the 3.8 S-type in the middle speed ranges and is just about level-pegging with the more powerful (but much heavier) Mk X. It is interesting to see that the least powerful of the quartet, the 210bhp 3.4 Mk. 2, is still the fastest we have tested suggesting: (a) that aerodynamically (and aesthetically too, perhaps) the Mk. 2 has the best body shape and (b) that the 3.8 Mk. 2 is probably still the fastest Jaguar saloon made. Perhaps we should add that Jaguar were disappointed with the top speed we recorded for the 420; they were expecting more.

For years, Motor has been praising the splendid old XK engine for its appearance, flexibility, power and smoothness and by ordinary standards it still excels in these departments. However, if you compare it with rival American V-8s with which a £2,000 Jaguar must compete, then it is no longer so impressive, especially on performance and smoothness at high revs. Not that there is much need to extend the engine beyond a fussless 4,000rpm — an easy 92mph in top — when there is no more than an efficient, deep growl from beneath the bonnet The engine always started promptly on its automatic choke but was sometimes inclined to stall when cold.

Inevitably the 420 has a fairly heavy thirst for petrol with a consumption between 15 and 18mpg according to how hard (and where) you drive.

The engine in our test car had an 8:1 compression ratio (7:1 and 9:1 are also available) and seemed quite happy to run on second best (four-star) grades without pinking. Since you get through one (of the two) 7-gallon tanks very quickly, it is easy temporarily to run out of petrol — which can be embarrassing if you’re overtaking. Fortunately, there is only a few seconds pause after operating the change-tank switch before the engine receives fuel again from the electric pumps — pumps which can be heard ticking when the engine is idling. The safe range of about 180 miles is the least grand touring feature of this Jaguar.

| Performance tests carried out by Motor’s staff at the Motor Industry Research Association proving ground Lindley. | ||

| Test Data: World copyright reserved; no unauthorised reproduction in whoie or in part. | ||

| Conditions | Weather: Overcast and gusty wind. Temperature 48°—49°F. Barometer 29.8 in. Hg. Surface: Dry tarmacadam and concrete (damp for max. speed runs). | |

| Fuel: | Four star 98 octane (R.M.) | |

| Maximum speeds | ||

|

Mean of two opposite runs Best one-way kilometre 2nd gear (max auto change speeds) 1st gear |

mph 115.0 117.7 78.0 50.0 |

|

| Acceleration times | ||

| mph | D1 sec | D2 sec |

| 0-30 | 3.5 | 4.7 |

| 0-40 | 5.2 | 6.9 |

| 0-50 | 7.0 | 9.2 |

| 0-60 | 9.4 | 11.8 |

| 0-70 | 12.3 | 14.7 |

| 0-80 | 16.3 | 18.7 |

| 0-90 | 21.6 | 24.0 |

| 0-100 | 29.8 | 32.2 |

| Standing quarter mile | 17.5 | |

| Acceleration times from rest |

kick down in D1 | |

| mph | sec. | |

| 20-40 | 3.2 | |

| 30-50 | 3.5 | |

| 40-60 | 4.2 | |

| 50-70 | 5.3 | |

| 60-80 | 6.9 | |

| 70-90 | 9.3 | |

| 80-100 | 13.5 | |

| Weight | ||

| Kerb weight (unladen with fuel for aproximately 50 miles) | 32.9 cwt. | |

| Front/rear distribution | 55.5% / 44.5% | |

| Weight laden as tested | 36.7 cwt. | |

| Fuel consumption | ||

| Touring (consumption midway between 30mph and maximum less 5% allowance for acceleration) | 17.9mpg | |

| Overall | 15.4mpg (=18.3 litres/100 km.) | |

| Total test distance | 2,600miles | |

| Tank capacity (maker’s figure) | 14gal. | |

| Speedometer | Indicated 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 | |

|

True 20 30 40 49 59 68 78 88 98 |

||

| Distance recorder | 0.2% fast | |

| Brakes | ||

| Pedal pressure, deceleration and equivalent stopping distance from 30 mph | ||

| lb. | g | ft |

| 25 | 0.32 | 94.0 |

| 50 | 0.76 | 39.5 |

| 75 | 1.0 | 30.0 |

| Handbrake | 0.37 | 81.0 |

| Fade test | ||

| 20 stops at 1/2g deceleration at 1 min. intervals from a speed midway between 30mph and maximum speed ( = 73 m.p.h.) | ||

| Pedal force at beginning Pedal force at 10th stop Pedal force at 20th stop | 33 39 42 | |

| Steering | ||

| Turning circle between kerbs: | ft. | |

| Left | 36 | |

| Right | 36 | |

| Turns of steering wheel from lock to lock | 2.9 | |

| Steering wheel deflection for 50 ft. diameter circle | 1.1 turns | |

| Parkability | Gap needed to clear a 6ft. wide obstruction parked in front | |

Transmission

Just as the engine feels smooth and remote for relaxed driving, yet rather fussy at speed, so does the American-built Model 8 Borg Warner automatic transmission have a similar dual character. On a light throttle, the gearchanging of this three-speed box — rather older in design than the more refined Model 35 fitted to most smaller British automatics — is quite smooth, if not imperceptible. But under hard acceleration at engine speeds above 3,500rpm there is a considerable jerk with each change, particularly if you lift your foot from the throttle suddenly. Similarly, kickdown changes to a lower gear are also rough and it pays in smoothness to anticipate down-shifts by moving the column lever yourself. Anticipation was essential on our test car because of a considerable delay before anything happened; when the change did come, it was so smooth on a closed throttle that all you felt was a gentle increase in engine braking. Under strong power, manual down- changes were invariably jerky but acceptable at part throttle.

The column lever, which has a light positive movement, has the familiar Model 8 settings — from left to right P (park), R (reverse), N (neutral), D2, D1 and L (the three forward ranges). On the assumption that most drivers who specify automatic transmission are not normally concerned about extracting the last ounce of performance, then D2 — which employs only intermediate and top gears — is the most satisfactory. So good is the engine’s low-speed torque that little performance is lost in D2 even if you do want the last ounce — as the accompanying comparative -figures (see page 16) between the two-speed D2 and three-speed D1 ranges clearly show.

With these various ranges there is a fair degree of manual overriding control. For instance, to prevent unwanted “hunting” between gears — which can happen — it is useful to hold second with a manual down-shift to L on a twisty road or steep hill. The only snag here is that below about 30mph low gear engages abruptly and will remain until the lever is moved back to D again. To avoid to-ing and fro-ing the selector, it would be better if the automatic engagement of first was delayed to much lower speeds as it is on the Model 35. Apart from a slight whine in first and another, even more subdued, that we noticed at certain cruising speeds from the final drive, the transmission is extremely quiet.

Handling and brakes

Like the Jaguar S-type, the Jaguar 420 has impeccable road manners. There cannot be more than two or three cars in the world that offer a better combination of ride and roadholding, two incompatible qualities that usually call for greater compromise than Jaguar have found necessary to make with their refined all-independent suspension. It takes a rough, cambered road, such as you often find in France, to show just how stable and safe this car can be at speed, and a long Continental journey (such as we made on two occasions in the course of an unusually high-mileage test) to discover the real meaning of Grand Touring. Paradoxically, this very English car seemed to reveal all its considerable qualities best when sweeping along the marathon through routes of France.

At first, we were less enthusiastic about the optional Varamatic power steering fitted to our car. It is pretty quick in response but the variable gearing — higher on lock than around the straight ahead position — calls for familiarization. Our first impression was that it felt a bit vague for gentle turns or simply for holding a straight line, but that it would respond with unexpected suddenness on a sharper corner. People unused to this characteristic found themselves darting into bends more sharply than they intended; but with a delicate smooth touch it soon becomes second nature to judge the amount of response to any given steering wheel movement, even though there is no proportional resistance or feel in the system. Its lightness helps to make long journeys, espepially those on a twisty roads, quite untiring and, of course, it is easy to lock the wheels over quickly when parking.

The telescopic steering column can be adjusted for length after releasing this knurled ring. Unfortunately, the column stalk controls do not move with the wheel.

Wide-section Dunlop SP41 tyres give tremendous adhesion: even in the wet it is often possible to use full throttle out of sharp corners without breaking the tail away or lifting the inside wheel. Normally there is mild, stable understeer but the rather sudden final degree of modest body roll announces that the back wheels are on the threshold of a slide. Significantly, not even our faster drivers can recall actually breaking adhesion, deliberately or not, to the extent that opposite lock correction was needed. On a dry road the tyres can squeal quite loudly (a common complaint against SP41s) though the 420, for all its high quality roadholding, is not the sort of car one habitually corners at squealing speeds. On bad rutted roads or sharp hump-back bumps the front can dip sufficiently far on its soft springs to scrape the ground.

Snap-shut door pockets provide a secure home for maps and books.

The all-disc brakes are excellent for normal use: despite a hint of sponginess from the strong servo, they are light to use and respond progressively to increased pressure. However, a 2,000ft descent of the Juras at modest speed with three people plus luggage on board caused such severe juddering that the brakes were practically unusable for 20 minutes. We confirmed this failing in our basic fade test at MIRA (20 jg stops from 73mph) when, although the rise in pedal pressure was small, indicating little fade, the onset of juddering after the sixth stop again made the brakes unpleasant to use. The composition of all brake pad or lining materials is inevitably a compromise between several conflicting ideals and the 420’s are apparently biased in favour of long life. We feel that on cars like this (Jaguar are by no means alone with the problem) the customer should be offered alternative pads with a clear explanation of what each type will do.

Recovery from the watersplash was immediate and the handbrake secured the car on a 1-in-3 hill.

Comfort and controls

Despite a slight “knobbliness” from the radial tyres at low speed, the ride is generally impeccable. If the ability to write legibly on the corrugated banked loops linking MIRA’s acceleration strips is anything to go by, then the ride is as level and shock-free as any we can recall. On some cars in the same situation, it is hard to keep pencil to paper, let alone write.

A telescopic steering column and reclining seat squabs help make the driving position outstandingly good. As in many expensive luxury cars, the armchair seats are splendidly comfortable in a showroom or on a motorway but their excessive width and slippery leather upholstery do little to hold you in place on a twisty road, despite slightly prominent shoulder pieces.

The contoured rear seat, bolstered at the front for thigh support, felt more comfortable than most and there is sufficient legroom for a six footer if the front seats are pushed forward at least four I notches. Further back than this, legroom is cramped at the back for tall people because the high floor (or low seat) dictates a knees-up position. This problem could be diminished by sinking foot-wells into the floor. Although widely separated from its side partners, the central folding arm rest at the back was much better placed than the individual ones at the front which, though useful tor, passenger location on comers, are of little use to the driver unless he has the steering wheel very close to his chest. If this means extending the column (rather than moving the seat forward) two fixed column stalks become well beyond finger-tip reach. Ideally, they should move with the wheel. A stronger spring loading would also be useful on the left-hand stalk to avoid flashing the lights when operating the indicators.

Although the fully reclining squabs overlap the rear seat, so that you cannot make a bed out of them, the backrests are sufficiently high to support your head when lying back for a rest.

Perhaps it is the tapered, fall-away bonnet that makes the 420 seem a smaller car than it really is from the driver’s seat. Although I you get a good all-round look-out, the screen pillars are a bit thick by current standards and the rear comers cannot be seen when reversing. Ignoring the badly adjusted dip beam on our car, the lights are excellent and show a clear advantage over rival systems using four small headlights.

The unusual heating system is quite effective once you have learnt how to use it. As on the S-type and 420G, a row of push buttons trigger the pneumatically operated air scoop and water valve. Just above is a temperature control slide flanked by two knurled knobs which regulate distribution between footwells and screen. The knobs are unmarked and you must memorize which way to turn them — not easy because they revolve in opposite directions to achieve a common result. A small to-and-fro lever in front regulates air flow to rear outlets on the transmission tunnel so back seat passengers don’t suffer from cold feet. Completing the system (making eight controls in all) is a two-speed fan which whooshes loudly like draining bathwater on its fast setting. Maximum temperature seemed modest, though always adequate in the weather we had; similarly, the throughput of air is not very high except at high speed with a window open to relieve internal pressure. As a ventilator in hot weather, the system is inferior to that of some cars — Ford Cortina, Hillman Minx, for instance — costing a third as much as the 420, although it is possible to mix a cool screen stream with warm air from below. Admittedly the front-hinged rear windows do have an extractor effect but they are awkward to reach from the driver’s seat and wind noise — normally quite low — is increased when they are open. Road rumble from the tyres is also modest and, as we have mentioned before, the hard hum of the engine obtrudes only at high revs. Generally, this is a quiet car.

Fittings and furniture

There is no denying that the familiar mass of dials and switches ‘set into an intricate expanse of timber looks very impressive, but no one could claim that this is the most practical, and it is certainly not the most ergonomic way of laying out a facia panel. The one concession to fashion that Jaguar have allowed themselves in the 420 is to surround the panel with a thick padded roll, partially spoiling the safety aspect by sinking a hard clock into the middle of it. The switches on the far left are a long way off although, provided you have an inertia reel safety belt, not beyond reach when you are strapped in. Jaguar drivers claim that you soon get used to locating the right switch but other people tend to grope feverishly at times and find the confusion considerable. Pushing them up for on (presumably for the sake of Americans who are used to it this way) does not help the newcomer, either.

The dipswitch is comfortably placed on the floor — where it should be in a two-pedal car. It is a pity, though, that the reluctant door catches do not operate with the same precision as most other hand controls. Old fashioned or not, all convenient spare space has been sensibly employed for some sort of accommodation: there is an under-facia tray, a facia locker and useful pockets in all the doors. The big boot, besides being finished inside as well as the rest of the car, will swallow a great deal of luggage — as our picture shows.

Standard interior fittings include a framed, dipping mirror, twistable sun visors, coat hooks, several interior lights, ash trays front and back, and a splendid set of good tools.

Servicing and accessibility

Engine oil changes and a number of routine checks are done every 3,000 miles, chassis lubrication (to 14 points) every 6,000 and transmission oil changes every 12,000 miles. In other words, the 420 needs quite a lot of regular attention. Surprisingly, the hand- book devotes 28 pages to routine maintenance — very useful to a small country garage entrusted with the work though we doubt whether many first owners will do their own servicing.

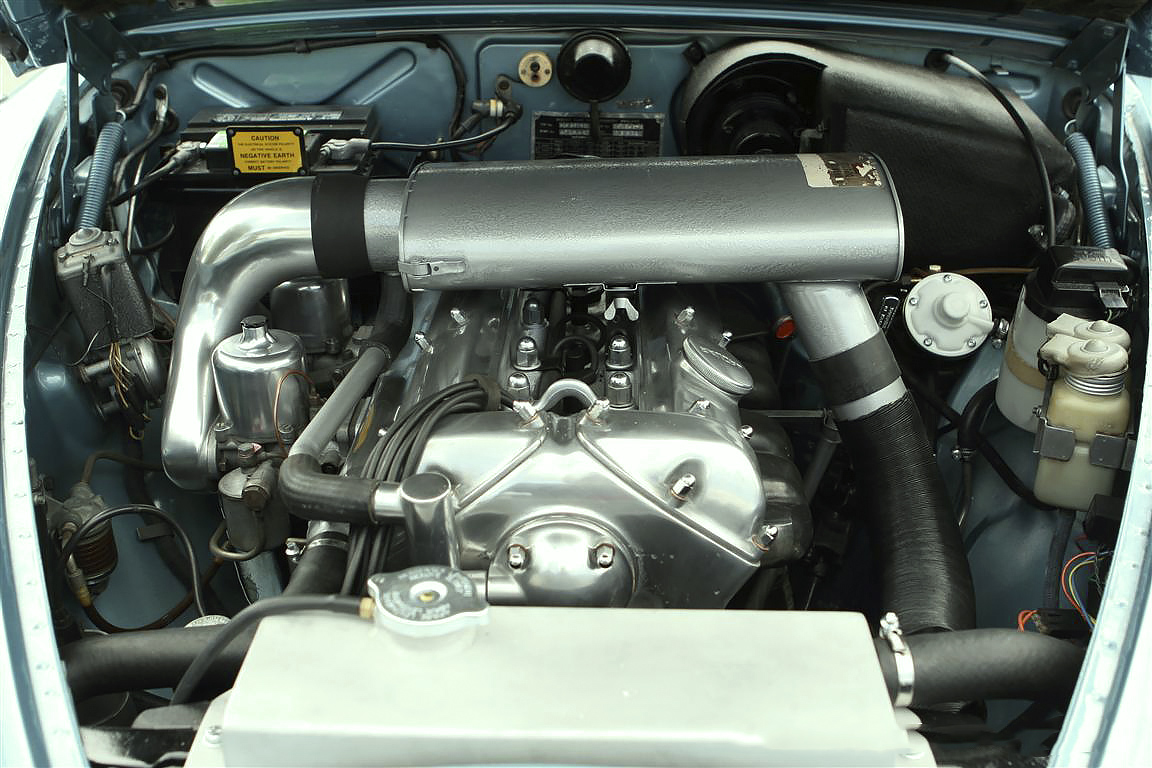

The magnificent looking machinery under the bonnet just asks for feather duster treatment. Accessibility is not bad, despite the crowding: the front carburetter, coil, hydraulic reservoirs, radiator cap, oil filler and automatic gearbox dipstick are easy to reach. The rear carburetter, distributor and engine oil dipstick are more difficult.

Whichever way you look at it, there is a strong family likeness between the 420 and the bigger 420G (ex Mk X).

The big armchair front seats are very comfortable for motorway driving but provide poor side support when cornering quickly.

The front seats must be pushed well forward if you want lots of legroom at the back. Both front squabs lie back.

The telescopic steering column can be adjusted for length after releasing this knurled ring. Unfortunately, the column stalk controls do not move with the wheel

Snap-shut door pockets provide a secure home for maps and books.

Jaguar 420 price 1967 : £1,569 plus £361 5s. 8d. purchase tax equals £1,930 5s. 8d.

Price as tested with automatic transmission and power steering, £2,132

| Car | 1967 Jaguar 420 |

| Made in | UK |

| Engine | |

| Cylinders | 6 in line |

| Bore and stroke | 92.07 mm. x 106.0 mm. |

| Cubic capacity | 4.235cc |

| Valves | DOHC |

| Compression ratio | 8:1 (7:1 and 9:1 also available) |

| Carburettors | Two SU MD8 |

| Fuel pump | Lucas electric |

| Oil-filter | Tecalemit |

| Max. power (gross) | 245bhp at 5,500rpm |

| Max. torque (gross) | 283lb ft at 3,750rpm |

| Transmission | Borg Warner Model 8 automatic transmission |

| Top gear | 1.00 : 1 |

| 2nd gear | 1.46 : 1 |

| 1st gear | 2.40 : 1 |

| Reverse | 2.00 : 1 |

| Final drive | Hypoid Salisbury with limited slip differential 3.31:1 |

| Mph at 1,000rpm in | |

| Top gear | 23.0 |

| 2nd gear | 15.7 |

| 1st gear | 9.6 |

| Construction /chassis | Unitary body |

| Brakes | Girlling discs all round |

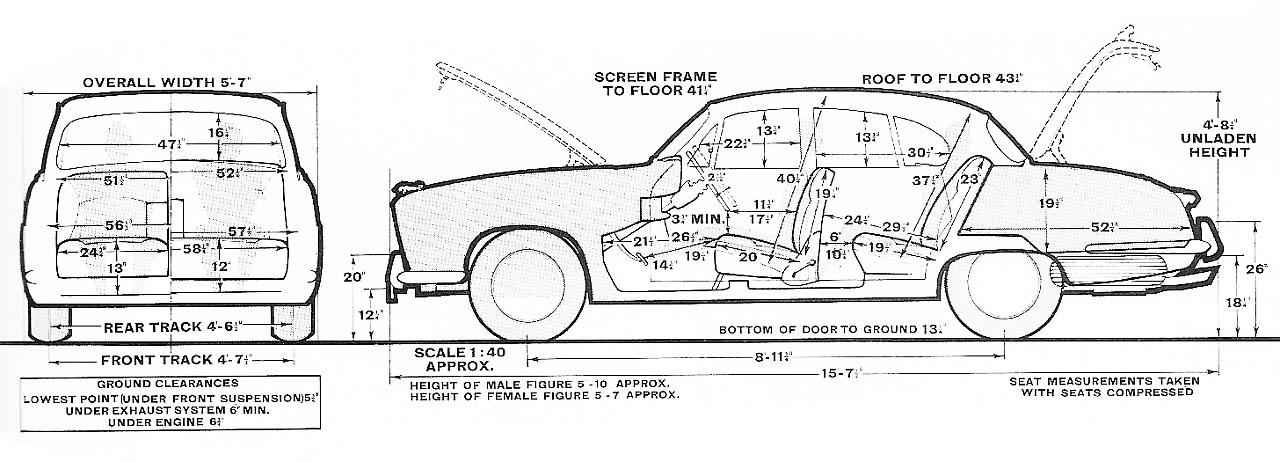

| Dimensions | 11.875 in. front. 10.395 in. rear |

| Friction areas: | |

| Front | 14.09 sq. ins. of lining operating on 229.2 sq. ins. of disc |

| Rear | 10.54 sq. ins. of lining operating on 189.6 sq. ins. of disc |

| Suspension and steering | |

| Front | Independent by coil springs and wishbones, the lower pair being connected by an anti-roll bar |

| Rear | Independent by lower links, half shafts and longitudinal radius arms with twin coil spring/damper units each side |

| Shock absorbers | |

| Front and rear | Girling telescopic |

| Steering gear | Adwes Varamatic power assisted |

| Tyres | Dunlop SP41 / 185 x 15 |

| Rim size | 5J |

| Coachwork and equipment | |

| Starting handle | No |

| Jack | Screw pillar with winding handle |

| Jacking points | 4 under door sills |

| Battery | 12-volt negative earth, 60 amp. hours capacity |

| Number of electrical fuses | 7 |

| Indicators | Self-cancelling flashers |

| Screen wipers | Self-parking, 2-speed |

| Screen washers | Lucas electric |

| Sun visors | 2 |

| Locks: | |

| With ignition key | Both front doors |

| With other keys | Boot and glove locker |

| Interior heater | Standard |

| Major extras available | Power-assisted steering, automatic transmission, overdrive, wire wheels, air-conditioning, steering lock, electrically heated rear window |

| Upholstery | Leather (for seats) |

| Floor covering | Pile carpet over felt underlay |

| Alternative body styles | None |

| Maintenance | |

| Sump | 12 pints S.A.E. 10W-30 |

| Auto gearbox | 16 pints A.T.F. |

| Rear axle | 2.75 pints S.A.i. 90 E.P. |

| Steering geair | AT fluid. |

| Cooling system | 25.5 pints (drain taps two) |

| Chassis lubrication | Every 6,000 milesto 14points, every 12,000 miles to 4 points |

| Minimum service interval | 3,000 miles |

| Ignition timing | 8° b.t.d.c. |

| Contact breaiker gap | 0.014-0.01 6 in. |

| Sparking plug gap | 0.025 in. |

| Sparking plug type | Champion N11Y |

| Tappet clearances (cold) | Inlet 0.004 in |

| Exhaust 0.006 in | |

| Valve timing: | |

| Inlet opens | 1 5°b.t.d.c. |

| Inlet closes | 57° a.b.d.c. |

| Exhaust opens | 57° b.b.d.c. |

| Exhaust closes | 1 5° a.t.d.c. |

| Front wheel toe-in | |

| Camber angle | 0—1 ° positive |

| Castor angle | 0 +-1/2 |

| Tyre pressures | 80p.s.i. front and rear |