DASH TO THE STASH

BMW M1 collection

The genius of the M1 E26 supercar – and why we really need a sequel

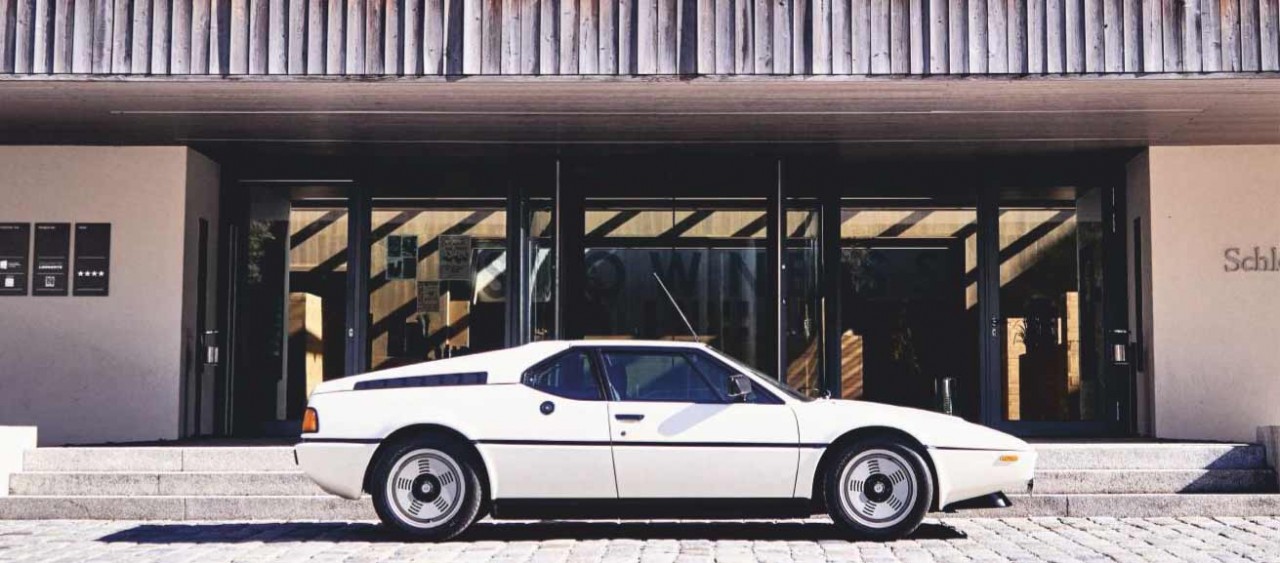

I’ve waited 40 years to drive an M1 E26, BMW’s mid-engine coupe. I know this one’s mine for the next two days, but something stops me rushing to the driver’s door. Some unseen power forces me to pause; to quietly absorb Giugiaro’s masterpiece.

Better to slowly walk around it, drinking it all in: the gentle wedge; the tiny kidneys in the so-low nose; the perfectly positioned BMW roundels, one on each rear corner; the horizontal line that runs the length of the body connecting so many elements of the M1’s so-pure shape. Is it flawless, I wonder? It’s certainly timeless and supremely elegant. As you get closer you appreciate how low it is: at just 1140mm high, the M1 is a staggering 154mm (six inches!) lower than a 911.

Despite the ultra-low profile, getting in is easy, and there’s plenty of room in the relatively plain interior. Excellent forward visibility through the huge windscreen is a supercar bonus. To the rear? Not so good. Compromises are few; wheelarch intrusion means the pedals are offset, and clutch travel is so long that my leg almost runs out of travel before the clutch bites. The ZF five-speed’s dogleg pattern means first is down and to the left. Yet, despite developing 243lb ft at 5000rpm and 270bhp at 6500rpm, so flexible is BMW’s wonderful 24-valve, 3.5-litre six that you only need first gear for moving away, or when crawling through Munich’s city traffic. This engine might be racebred but it doesn’t feel it. The gearchange is so explicitly mechanical in its action you can feel the individual components engaging, particularly between second and third.

Engine noise is never less than glorious. Accelerate hard and the six soars to a hard-edged intake symphony that’s overtaken by an exhaust snarl at 6000rpm. Autobahn traffic thinning, the M1 sprints towards its top speed. No, it doesn’t feel supercar quick – 0-62mph takes 6.0sec – but it’s eager and responsive. Here – and on winding roads, I’ll later learn – composure and stability are staggering. By today’s standards, the modest tyres mean grip levels are less than heroic, but the advantage is the kind of involvement and feel that too many modern supercars lack. The only serious flaw is heavy steering below 30mph. At proper speeds, the steering – remember, the M1 saw BMW’s first use of rack-and-pinion – is direct, and a point of intimate interaction between driver, front tyres and the road.

IS IT FLAWLESS, I WONDER? IT’S CERTAINLY TIMELESS AND SUPREMELY ELEGANT

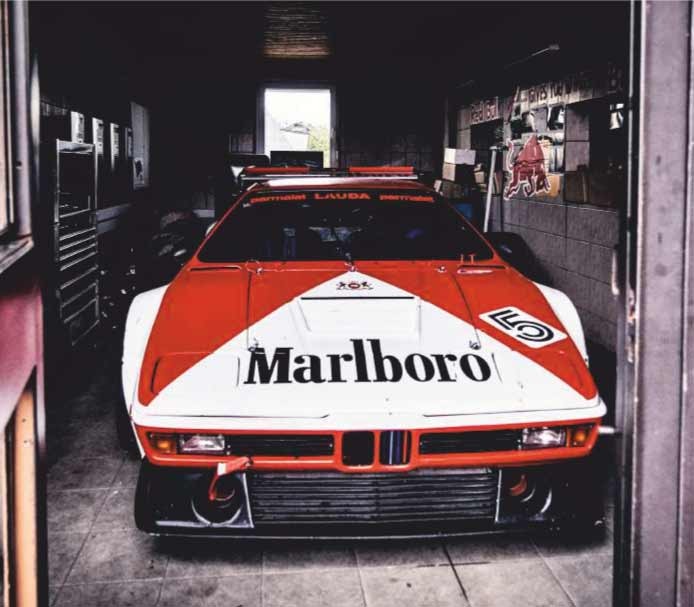

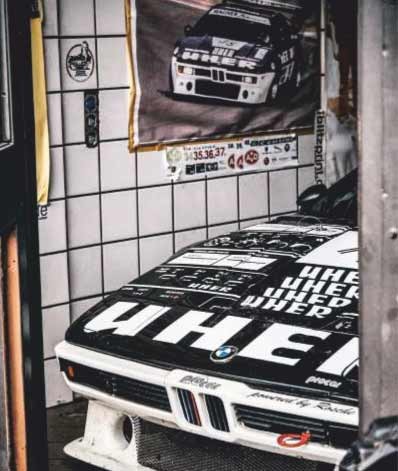

We’re on our way to see Fritz Wagner. An obsessive visionary, compulsive collector and gifted mechanic, Wagner has cornered the world’s supply of M1s. Not just cars – he has five, and maintains at least 14 Procar race versions – but all the spares required to build at least another couple from scratch. Not for Wagner a well-organised warehouse, meticulously laid-out and arranged by some advanced computer program. Instead, the collection spreads chaotically through half the ground floor of his 100-year-old home and spills out in a variety of ramshackle outbuildings, scattered around what has, by default, become a large courtyard.

Nothing prepares you for the shock of seeing the myriad M1s, plus the stock of thousands of associated parts. The reality is, if your M1 fails and you need a replacement component, Fritz Wagner is your only option. ‘If something breaks down, people come to me and exchange old versus new,’ explains Wagner. ‘I’ve never made a deal out of it. I’m happy keeping these great cars on the track and the road.’

Only Fritz and perhaps son Marco comprehend the disorder, and instantly know how to find the required part. The rest of us stare in amazement at the seeming chaos. Five complete M1 engines line up on the wooden floor of one shed. Eight crankshafts sit on shelving in another. Visible elsewhere are 23 cylinder heads, a number of pistons, wheel hubs, brake calipers, suspension arms, alternators, even a stock of the M1’s BMW roundel. Body parts, moulds and door frames hide in the attic of another, accessed only by stepladder.

Old photographs and posters of hero M1 drivers – Niki Lauda, Nelson Piquet, Manfred Winkelhock, Christian Danner and Hans-Joachim ‘Striezel’ Stuck – line the walls. One of Piquet’s old helmets sits on the back of his Procar M1. One room, inexplicably, contains nothing but piles of rags. Trophies and alternators fight for space on and in a cheap wooden display cabinet in another. Drawers are open, filled with washers, bolts, screws and wiring looms. Old race tyres are stacked high outside. Seats, wheels, springs and complete exhaust systems lie on the floor. It is impossible for an outsider to discern any system to their organisation.

‘I ONLY HAVE TO OPEN THE GARAGE TO SEE MY REMBRANDTS’ FRITZ WAGNER

Apparently when Hans Stuck first visited Wagner, he told Fritz, ‘Now I have to go home to sleep to capture this in my head.’ Why, I can’t help asking, are the collection of M1s and all the parts not maintained as part of BMW Classic’s 1400-strong car and motorcycle collection? Superbly organised and, since 2016, contained in over 13,000 square metres of structures including a handsome 1918 building (the oldest surviving BMW property) that serves as the cafe/foyer, archive and museum, Classic is walking distance from BMW’s Munich HQ. ‘We’ve talked about buying Wagner’s collection,’ admits BMW Classic’s Benjamin Voss. ‘But Classic knows where the cars and the parts are, that they are safe, and that we have access to them, so we are happy.’

It could be a BMW’s 911

How did this near-priceless collection come to be in the hands of Fritz Wagner? Priceless? To give you an idea of its value, the M1 I’m driving (one of five in BMW’s collection) is insured for £660,000.

Over an al fresco lunch, Fritz, now 66, stocky, friendly, permanently in overalls, his handshake forceful, the dirt and oil of his work ingrained into his hands and fingernails, his long hair thick and matted, explains. When, as a 24-year-old racing mechanic and passionate motorsport fan, Wagner first saw sketches and photographs of the M1 in 1977 he knew it was ‘the car of my life’.

Wagner well knows the complicated M1 story. In the early ’70s BMW, then still a minor player, wanted to lift its profile through racing. Jochen Neerpasch, lured from success as boss of Ford racing operations in Germany, established BMW Motorsport GmbH as a separate company. With BMW’s heavy 3.0 CSLs becoming uncompetitive, Neerpasch set out to create a new Group 5 silhouette racer.

‘The idea was to build a racing car and convert it to a road car,’ Neerpasch tells me a few days after I drive the M1. ‘We wanted to price the road car at 100,000DM and the racing version at 150,000DM, when our racing E9 3.0CSL cost 350,000DM. We also wanted Paul Rosche [BMW’s engine man] to develop a new 3.0-litre V8 engine that could also be used in a Formula 1 car.’

BMW Motorsport project E26 called for 800 cars in left-hand-drive only, to be built by Lamborghini, spaceframe construction, a twin-cam, 24-valve version of BMW’s inline six delivering 260bhp as a road car and 456bhp in racing form, and a fibreglass body styled by Giugiaro. Lamborghini’s Gianpaolo Dallara, fresh from the Miura and Countach, assisted Neerpasch and Martin Braungart, who ran the project, in developing the car.

‘It was a fantastical technical co-operation,’ according to Neerpasch. ‘At least once a week in 1977, taking turns, Martin and I would drive from Garching to Sant’Agata, getting faster and faster as we improved the car, each trying to beat the other’s time [he doesn’t remember who won]. In the end we cut 30 minutes from our time.’

Then Lamborghini’s financial problems hit. The request for a loan from BMW was denied. Neerpasch arranged for trucks to collect all the prototypes and everything related to the M1 from Sant’Agata. BMW’s solution, after the board decided not to buy Lamborghini, was to have the car assembled by Giugiaro’s Italdesign in Italy, with Italian suppliers providing the spaceframe and body. The cars were then trucked to Baur in Germany for installation of the BMW hardware. Finally they were sent to BMW Motorsport for quality assurance. Inevitably, all the complications led to drastic cost increases.

The dramas meant the M1 launch was delayed by two years, to February 1979. Production finally ceased in March 1981. In the end just 399 M1 road cars were built, plus another 54 race versions, this number made up of 48 complete cars and six chassis that have since been assembled.

Neerpasch also convinced Max Mosley and Bernie Ecclestone to create a still-unique one-make race as part of the European F1 race weekend. The BMW Procar championship took the best five F1 drivers (except those from Ferrari and Renault) from Friday’s practice and mixed them with successful GT and Touring Car drivers, all racing in supposedly identical M1s. The championship lasted two years, 1979 and 1980, and was won by Niki Lauda and Nelson Piquet respectively. Their prize: a new M1.

When buyers baulked at the 100,000DM price (roughly £137k in today’s money), BMW began to lose interest. When the silhouette formula was cancelled in 1980, the motorsport budget was cut by two-thirds and not even Neerpasch’s brilliant strategy of the one-make Procar series could save the M1 – or his career at BMW.

By this time Fritz Wagner was a freelance mechanic building Procars for Helmut Marko, and later the Cassani Racing team. Striezel Stuck won the last two races of the 1979 series with Cassani, instantly raising Wagner’s profile as the go-to Procar mechanic. But by then BMW wanted nothing to do with the M1, and was far more interested in becoming an F1 engine supplier to Brabham. By 1983 the M1s and all their componentry were just sad old racing cars, little better than scrap.

Eventually, in 1984, with nowhere to store all the M1 stuff, Motorsport suggested Wagner take the lot for 100,000DM, a quarter of their real value. He was allowed to sell any of the parts except for the engine, and BMW insisted that if it needed any bits they could buy them back. The collection included the original E26 prototype – four of the five prototypes had been destroyed in crash tests – visually identical to the production car apart from two wipers, different wheels and no BMW roundels on the rear corners. Wagner adds about 600 miles a year to its odo.

Wagner’s dream business, helping owners of the soon-to-be-coveted M1, was set for life. And still there was motor racing. The revival of Procar racing as a support event for the 2008 German Grand Prix and again in 2019, to celebrate the series’ 40th anniversary, took Wagner back to preparing M1s for many of the drivers, including Stuck. There are other historic events like the Daytona Classic 24-hour race.

‘Ten years ago my cars were the fastest,’ Wagner tells me. ‘Not now. New materials, small tolerances and new parts mean some cars have more power. I only use the original parts and would never use reproduced parts.’

He says he races for fun, not for the money, and swears he no longer keeps accounts.

‘I never take holidays – every day is a holiday,’ says Wagner, who admits to working 15-hour days. ‘I am living in the right time with the advantage of real freedom. For me, progress stopped in the ’80s. I don’t have a cellphone or a computer.’

‘I quickly learned the only way to contact Fritz was to ring his landline telephone at lunchtime,’ confirms BMW Classic’s Benjamin Voss. Says Wagner, ‘I don’t need to go into the basement and open the safe to look at a Rembrandt. I only have to open the garage to see my Rembrandts.’ Fritz Wagner keeps a few alpaca ‘as a distraction from the cars’ but it’s impossible not to conclude that the M1 is everything to the man.

It’s a testament to the development skills of Neerpasch, Braungart and Dallara that the M1, conceived as a racing car, became the most civilised of all the late-’70s/early-’80s exotic supercars. A commercial failure, the M1 truly is one of the great cars.

Says Neerpasch, ‘If the M1 had been properly developed it could have been like the 911. BMW needs a car like this urgently, and they don’t have one.’ (The wait for the M1-inspired, next-gen i8 goes on.) With the car safely returned to its keeper, I can’t leave the M1 without walking around it again. Twice. Yep, flawless.

Steering, once you’re up to speed, is a thing of joy Fritz Wagner: If you’re going to hoard, make it M1 stuff ‘What’s behind this door…? Ah, of course’ Here, the Procar race series lives on – silently The poster might be almost affordable All the M1 engines you could possibly need, or want.