Porsche 911 vs Alpine A110 rally heroes for the road. Can racy Renault top style icon 911? Alpine is back in the headlines with its new A110, but how will the original fare against the all-conquering Porsche 911? The A110 was a rally hero, but can it triumph against its rear-engined rival on the road, the mighty Porsche 911? Words Greg Macleman. Photography Tony Baker.

ALPINE’S TRIAL REAR-ENGINED REVOLUTION

It’s a crisp autumn day in Bedfordshire and a quiet calm has returned to a scene that moments before was frantic with the squeal of tyres and the howl of flat-six battling highly strung ‘four’. The leaves barely have time to settle before the silence is once again shattered by a sublime 1965 Porsche 911, swinging into frame behind it the squat streak of French Racing Blue worn by its great period rally foe, the Alpine-Renault A110. Astounding motorsport history is justification enough to pit these rear-engined masterpieces against one another, but theirs is a rivalry that began long before the World Rally Championship, stretching back to the aftermath of the Second World War as two brilliant engineers simultaneously set about the same task: to create the world’s greatest sports car.

For Prof Dr Ing Ferry Porsche, ambition was born of necessity as he took charge of the family business while his father, Ferdinand, languished in a French prison accused of war crimes. The war had been kind to the firm thanks to its involvement with Volkswagen, and the engineer – who had a hand in designing the People’s Car – set about creating the company’s first production sports car. Porsche undoubtedly had a head start thanks to three Type 64 Reutter-bodied racers built before the war, which served as inspiration for the coupé that followed. Temporarily decamped to an old sawmill in Gmünd, Austria, the first production Porsches – lightweight, aluminium-bodied 356s that helped the firm foster a reputation in competition – began to roll out of the workshop in 1948; the first race in which the 356 was entered, in Innsbruck, it won. While a young Ferry Porsche was heading for Gmünd to start work on the 356, over in France Jean Rédélé had become Renault’s youngest-ever concessionaire at the tender age of 25.

Based in Dieppe, he scratched together a living selling off war surplus while struggling to shift leftover stock of aged Juvaquatres, before the arrival of the 4CV in 1947. Rédélé, who had a passion for motorsport, immediately began modifying the diminutive rear-engined saloon, endowing his Type 1063 with a host of in-house upgrades including a five-speed gearbox to which he owned the manufacturing rights. The gifted driver’s faith in the 4CV was rewarded early on, as Rédélé and co-driver Louis Pons steered the car to a fourth-place finish on the 1951 Rallye Monte-Carlo, claiming a class win on the gruelling Mille Miglia the following year.

Though competitive, the 4CV was a far cry from Rédélé’s idea of the perfect sports car. Following his success, the racer began to drum up interest in a new type of machine, based on Renault mechanicals but lighter, lower and more focused. His enthusiasm fell on deaf ears at Billancourt, so he took matters into his own hands and commissioned Giovanni Michelotti to pen a body to be built in Italy by Allemano.

Incredibly, the 1063-engined, aluminium-alloy Rédélé Special won on its first outing, the 1953 Rallye de Dieppe. By 1954, a steel body had been built, which was used as a buck for three polyester- bodied versions that took a bow in Paris as the A106 the following year.

The biggest change to the line-up came in 1957, when Rédélé took the first steps towards doing away with the ageing 4CV platform on which all his previous efforts had been based, trialling an in-house steel-tube chassis that made its debut in the A108 Cabriolet and became a key component of the A108 Berlinette Tour de France and all future Alpines. That car served as the basis for the firm’s most successful model and the machine that would take the fight to Porsche on the special stages of Europe and Africa – the A110. Rédélé’s recipe was finally perfected in 1962, when the beautiful glassfibre A108 body was mated to a single-tube backbone chassis and the advanced running gear of the brand-new R8, which brought four-wheel disc brakes, a sealed cooling system, and a reliable five-bearing engine bursting with potential.

While Rédélé was taking his early creations rallying, Porsche had returned to Germany and taken up residence in Stuttgart, where Karosserie Reutter began producing steel-bodied 356s. Unlike the French outfit, Porsche had the backing of a major manufacturer from the off, with Volkswagen agreeing to sell and service the new sports car. Very soon, Porsche components started to replace those from Wolfsburg, beginning with the firm’s synchromesh system that edged out the VW crash gearbox in 1952; by the end of the decade, very little of the model’s Volkswagen ancestry remained.

Development of the 356 continued, peaking with the four-cam Carrera powered by an all-new competition engine designed by Dr Ernst Fuhrmann and available in 1500, 1600 and 2-litre guises until 1963. Despite this, the 356 was outpaced and outdated, opening the door for a replacement with more room, a longer wheelbase and greater stability. Styling projects headed by Ferry’s son ‘Butzi’ eventually led to the Type 7, from which the 901 (as it was known before Peugeot’s objections) materialised, emerging to critical acclaim at Frankfurt in ’1963.

Both Alpine A110 and Porsche 911 were the product of careful evolution, but it was the German coupé that took the furthest step from its predecessor. Still rear-engined and air-cooled, early 911s were fitted with a 2-litre, six-cylinder unit producing 130bhp at 6100rpm and fed by three single-choke 40PI Solex carbs per bank, while MacPherson strut front suspension allowed for a decent-sized forward luggage compartment. A semi-trailing-link configuration was used at the rear, doing away with the swing-axles of the 356, with each wheel hub carried by a suspension arm that pivots on a bracket just behind the rear crossmember.

As well as being cheap to produce, the compact set-up allowed for two small back seats. Almost as important as the mechanical improvements were styling changes, and though the family resemblance is still clear to see, the shapely silhouette of the 911 seems light-years ahead of the upturned bathtub 356. More pronounced front wings and an acute bonnet line brought the 911 bang up to date, as did the sharper tail and well-integrated rear lamps – though the iconic Fuchs wheels were still a few years off. The slab sides and narrow track somehow bring to mind a smart tailored suit, particularly when viewed alongside the more intricate Alpine, an impression that’s reinforced by the stunning condition of ‘our’ early short-wheelbase, which is finished in Signal Red and is not long out of restoration by Dennis Nachtigal in Germany. Open the long, vault-like doors and the interior more than lives up to expectations, the modern plastics of the new generation softened by wood accents that match the striking tan leatherette and Pepita seats – prim and proper rather than sporty in factory trim. Something of the 356’s character does remain, however, in the large-diameter steering wheel, behind which you sit upright with a clear view of the low, swooping bonnet.

The promise of 0-60mph in just 8.3 secs and a top speed of 131mph makes you keen to fire up the Porsche’s famed flat-six – a process that requires plenty of throttle and a bit of patience. When it does catch, the silence is broken by a wonderfully throaty bark that’s instantly familiar, a deep and guttural sound that over-promises in the best way. Underlining the 911’s sporting pretensions is a five-speed dogleg ’box, which slots into first with ease, and you pull away with a hefty prod of the floor-mounted accelerator and a clatter of air-cooled engine noise. It picks up quickly, with a precise gearchange that belies its remote operation – performance is instantly accessible and encourages you to push on, the low-down lumpiness disappearing with speed. The ‘six’ really comes alive as you wind up the revs, on a wave of top-end power.

Early cars were dogged by unpredictable handling, partly due to extra engine weight that its designers hadn’t anticipated, but also variations in production that threw out carefully planned suspension geometry. The car quickly gained a reputation for a lively rear end when driven hard; but as good-natured as a pitbull may be, you wouldn’t poke one in the eye, and as long as you’re not silly the 911 handles beautifully, erring on the side of understeer. In its purest form, the Porsche is a joy.

If the 911 is straight from Savile Row, the A110 is decidedly smart-casual. Unlike the immaculate Porsche, the Alpine wears its scars with pride, its low nose pockmarked with stonechips and touch-ups from a lifetime of being driven as its designer intended. If anything, it looks better for it. The Alpine’s design is unlike anything else, both beautiful and purposeful, muscular and delicate, and is undeniably the more striking of the two. Perfect proportions make its size difficult to judge in isolation, but parked next to the 911 – itself a small machine – the jewel-like Alpine seems even more of a toy.

My 5ft 11in frame is enough to give owner Geoff Simpson cause for concern, and there’s talk of getting the spanners out to adjust the bucket seat. But with a bit of snake-hippery it’s possible to slip behind the wheel, albeit backside- first, and once there the tiny cabin is remarkably comfortable. Ahead of the steering wheel, an enormous speedometer and tachometer fill the binnacle, while to the right a host of gauges, switches and a rally timer are later additions. The driving position is comfortable where it has no right to be, with both wheel and pedals offset, the latter shunted towards the centre of the car to make room for the wheelarch.

Alpines were built under licence all over the world, with Dinalpins produced in Mexico, Bulgaralpines in Eastern Europe and FASA putting cars together in Spain. This example is one of the latter, and left the factory with a standard 76bhp 1300 engine, but, as with most A110s, has since been modified. The most notable – and most exciting – change is the engine, which has been replaced by a 1397cc crossflow unit built by renowned fettler Salv Sacco. Fed by twin 40DCOE Webers, it promises over 100bhp at the screaming end of the rev range, along with a more aggressive throttle response.

With the master switch on, the little Alpine starts readily, filling the glassfibre shell with a busy engine note before settling to a remarkably relaxed idle – but the hair-trigger accelerator is too tempting not to blip like a teenager waiting at the lights. Pull away and its slight 695kg weight is immediately apparent, with blistering acceleration that straight away puts it in a class above the torquey but 385kg heavier 911. Throttle response is instant and the four-speed ’box slick, but no real match for the hot engine that just wants to keep going and going – Simpson’s next modification is a five-speeder that’s currently winging its way from Scotland, and should transform the car. Even at the same speed the Alpine feels the quicker of the two, partly due to its size and low ride height, but also the theatre that accompanies each blast up the rev range.

It’s an addictive experience only enhanced by the A110’s roadholding, which is nothing short of remarkable for a car with a comparatively archaic swing-axle arrangement at the rear. It, too, carries its timber over the back wheels, but the lower centre of gravity and wide track help tame the tail, which offers bags of confidence-inspiring feedback. Feeding the tiny sports car along the country lanes of Newport Pagnell, it’s easy to see how Alpine toppled the mighty 911 from its rallying perch, becoming the go-to loose-surface and Tarmac weapon before the arrival of the all-conquering Lancia Stratos.

Jean Rédélé and Ferry Porsche each took the thick end of 20 years to achieve their goals, with the final outcome similar in some respects and very different in others – like twins with wildly differing personalities. Which is the evil one depends very much on your idea of the perfect sports car, whether that is the effortless chic and engineering prowess of the Porsche 911, or the Alpine’s quest for total performance from the most humble of beginnings. Both triumphed for a time on the world’s rally stages, but only the Porsche became a commercial success. Crucially, this allowed it to develop as a road car and, where the A110 remained true to Rédélé’s vision, the pure ‘901’ quickly gave way to bigger engines, swollen arches and supercar performance.

By the time the detuned, last-of-the-line Alpine A110 1600 SX left the factory in 1977, the 911 had grown into a whale-tailed, turbocharged 3.3-litre road-burner putting out more than 300bhp. It might have been fleeting, but there was a time when Alpine was king.

Thanks to Export 56 (www.export56.com); Stephen Dell; Tim Moores; Renault Alpine Owners’ Club (www.renaultalpine.co.uk); Club Alpine Renault (www.clubalpinerenault.org.uk)

‘It starts with a wonderfully throaty bark and comes alive as you wind up the revs on a wave of top-end power’

Clockwise from opposite: purity of short-wheelbase original is a thrill; early cars had six Solex carbs, later changed to a pair of triple-choke Webers; little rear legroom; skinny rear tyres contribute to lively handling; classy cabin offers comfort a level above that of the A110; pre-Fuchs steel wheels; gold badging for first 911s. Clockwise from opposite: distinctive transverse exhaust; Alpine name has recently been revived; Gotti competition alloys and snow tyres; rally-ready cabin is more spacious than it looks; handling is sublime; huge dials fill diminutive dash; modified engine bay has a Porsche 944 radiator paired with motorcycle electric fans.

‘The A110 is addictive, the roadholding nothing short of remarkable for a car with a comparatively archaic swing-axle rear’

ON THE LOOSE

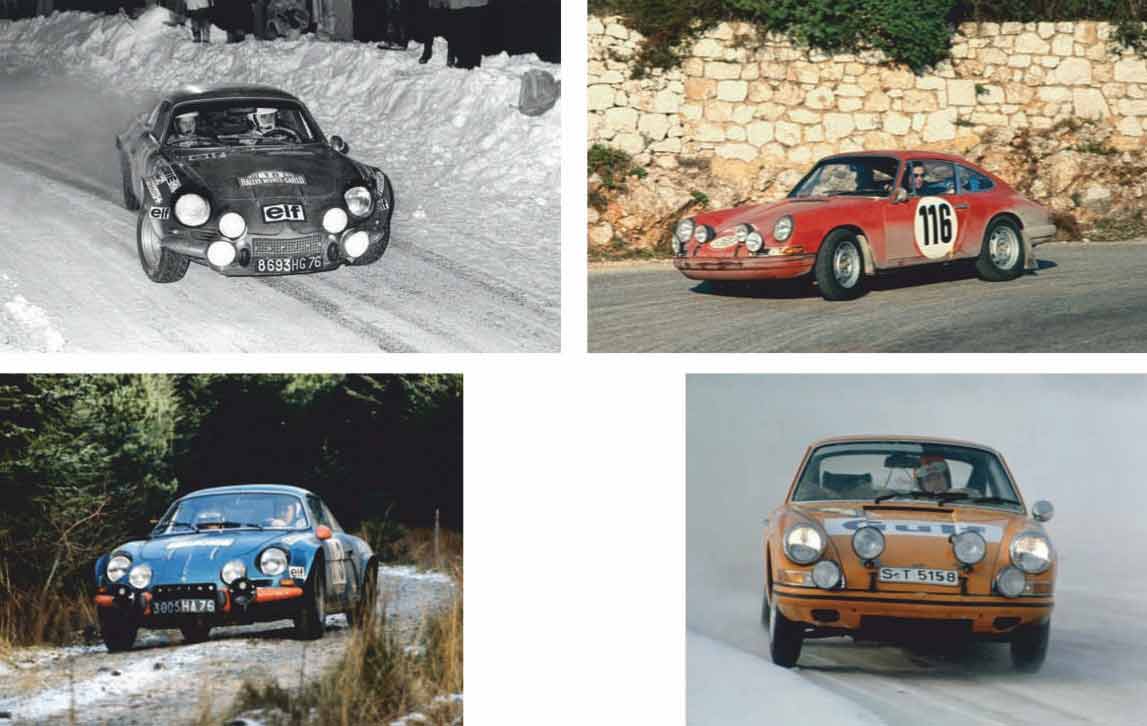

Rear-engined traction helped these legends make their names on the rally stages. Words Greg Macleman. Photography Motorsport Images.

The Porsche 911 was unveiled to the public in 1964, and made its competition debut just a year later on the Rallye Monte-Carlo with Herbert Linge and Peter Falk. The pair quickly demonstrated the Porsche’s suitability for the special stages by taking a relatively standard car (warmed-over to 160bhp) to fifth overall, with Günter Klass’ 1967 German National Rally Championship title underlining the 911’s untapped potential.

Peculiarities of homologation rules allowed Porsche to make an all-out assault on international rallying in 1967, entering the 912 in Group 1, the 911L in Group 2, the 911T in Group 3 and the 911S in Group 4. Vic Elford, who was recruited from Ford, proved dazzling, winning the Deutschland Rally, Tulip Rally, Tour de Corse and Geneva Rally, and finishing third on the Monte. The Brit won the headline event at the second time of asking in 1968, in a season that the 2-litre German coupé dominated, with victory in no fewer than six other rallies; Pauli Toivonen won the European Championship and Porsche finished third in the International Championship for Makes.

The arrival of the 2.2- and 2.5-litre 911s on the international rallying scene in 1970 continued the success, building on four years of racing experience with ever-increasing performance. Waldegård and Helmér won the Monte, Swedish Rally and Austrian Alpine on their way to victory in the International Championship for Makes and further success seemed likely, but Porsche’s attention turned to the Safari Rally and its other competition obligations, and the factory eased back its involvement in rallying. By the early 1970s the 911’s dominance was under threat, with the greatest challenge coming from the lightweight Alpine A110.

Jean Rédélé was no stranger to rallying, going so far as to name his firm after his favourite event as a driver, but the cutting-edge A110 had a slow start on the international scene. The model always seemed to be playing a game of catch-up between the engines that were available and what was required to win rallies; despite Gérard Larrousse leading the ’1967 Coupe des Alpes and crashing out of the ’1968 Monte in a promising position, big wins eluded the marque until Renault threw its weight behind the programme.

With the backing of La Régie, the renamed Alpine-Renault’s fortunes began to turn. The 1500-engined cars took three wins in 1968 and ’1969, while the R16 TS-powered A110 1600’s arrival was hampered by silly mistakes and poor reliability. The 1300 bowed out in 1970 with third for Jean-Pierre Nicolas on the Monte; following a disastrous showing against the 911 in that event, the 1600 finally demonstrated its potential thanks to Jean-Luc Thérier, who won the Sanremo and Acropolis. Outright victory on the Monte heralded the arrival of former Ford ace Ove Andersson in 1971, followed by International Championship for Makes and French National Championship wins the same year.

The A110’s greatest success came in 1973, when it swept away all comers in the inaugural season of the World Rally Championship, with 1-2-3 finishes on both the Rallye Monte-Carlo and Tour de Corse. It proved to be a career high for the model, which was roundly beaten the following year as WRC laurels passed to Lancia with the first of three consecutive titles.