From Bavaria to the West Country… Two aeronautical giants and one chassis design that would undergo 75 years of evolution. Here’s how pre-war BMW 326 sired post-war Bristol 400. Words Simon Charlesworth. Photography Tony Baker.

MEET THE ANCESTOR Post-war Bristol 400 gets acquainted with its pre-war BMW 326 progenitor.

Brooklands is yet to open. It’s early, empty and hushed when we drive through the Campbell Gate. We proceed slowly. The 21st-century rush-hour, with its dawdling traffic, frustrated commuters and booming radios, shrivels in the rear-view mirror.

It’s been a few years since I last visited this site, but you soon notice the differences. The big draw to me, however, is something that remains the same: the 111-year-old motorsport relic. It is an essential petrolhead pilgrimage, to come and bear witness to the exalted remains of the world’s first motor-racing circuit.

We’re here to retrace the evolutionary footsteps between Mike Dawes’ 1937 Frazer Nash-BMW 326 and Michael Barton’s 1946 Bristol Type 400. Why Brooklands? It was one of the venues where AFN Ltd (see panel) demonstrated the sporting talents of its Frazer Nash-BMW models. Headlines included HJ Aldington at the 1936 MCC High-Speed Trial posting 98½ miles in the hour, before this was beaten in 1937 by Sammy Davis, who hit 103.97mph. Both records were set by the 328, which became the first sports car to average over 100mph in the hour. We’re also here because of Brooklands’ other significant history: the site hosted part of Britain’s aeronautical industry, which dovetails with the main business concerns of both BMW and the Bristol Aircraft Company.

BMW’s progress as a car manufacturer was nothing short of astounding – but then, so were the levels of the firm’s funding from the German state. In October 1928, BMW purchased Fahrzeugfabrik Eisenach AG from Gothaer Waggonfabrik and continued to manufacture the licence-built Austin Seven, the Dixi 3/15 DA-1. BMW produced its first design in 1932 – the 3/20 – after cancelling the Austin licence. Interestingly, the ‘3’ denotes BMW’s third line of business, ‘1’ used for its aero-engine interests and ‘2’ for its motorcycle division.

Remarkably, by 1933 the company had launched its first six-cylinder model, the 1200cc 303. This was the first BMW to bear the ‘double-bean’ grille and it would form the basis of both the 1.5-litre 315 and 1.9-litre 319. The 319’s successor, the 1971cc 50bhp 326, was built between 1936 and ’1941, with production totalling 15,936. Designed by Dr Fritz Fiedler and styled by Peter Schimanowski, it was BMW’s first four-door car and the first with hydraulic brakes. It sat on an extremely rigid A-frame box-section chassis with front suspension via a transverse leaf spring and upper wishbones: the Austin Seven might have gone, but its influence was not forgotten. The live rear axle was suspended via longitudinal torsion bars, with double-acting dampers fore and aft.

The 72mph 326 would sire the 320, 321, 335 and the 327 (the chic short-wheelbase leaf-sprung coupé), while its 66 x 96mm M78 engine block underpinned the 328’s M328 engine. The M328 was crowned with a clever higher-compression Schleicher-Flemming cylinder head and capable of 80bhp at 4500rpm – this unit was also installed in the low-volume 327/28.

“There’s a lovely bit in the BMW board minutes from 1947,” explains Mike Dawes, who is also the treasurer of the BMW Historic Motor Club (UK), “when they’re lamenting making anything they can – knives, folks, saucepans and the like. To this, the finance director said: ‘We’ve got to face the fact that we are no longer being financed by the Reich Aviation Ministry.’ Göring was financing practically everything and this shows in the engineering of these cars.”

In Filton, come peacetime and the cancellation of War Office orders, BAC’s MD, Sir George Stanley White, knew that alternative work had to be found for the firm’s 70,000- strong workforce. Among BAC’s new ventures, Sir Stanley’s son, George SM White, founded in 1945 what would become the Car Division. This mimicked a move BAC had taken after the Great War, which led to two prototype Monocar light cars and body-building contracts for Armstrong Siddeley and sister company Bristol Tramways’ Motor Department. However, doubtless recalling its experience with the Monocar and early aircraft designs, the company decided during the war to acquire an existing motor manufacturer.

The Aldington brothers of Frazer Nash, meanwhile, were keen to use their UK licence to manufacture BMWs and re-establish contacts with the firm. Their plan was to put the 326 into production, but there were problems: firstly, the Midlands’ short-sighted motor industry was not interested; secondly, the Ambi Budd factories, which had produced the 326’s body, were either completely destroyed or under Soviet control.

AFN could see that BAC would benefit from its manufacture and trade experience, while AFN, which lacked production facilities, would no longer have to deal with hostile sentiments around its products, which had been pungent enough before WW2; by late ’1937, it was common for AFN to conceal the ‘Made In Germany’ engine-bay plates by fitting them face down.

An agreement was reached and BAC bought a majority stake in the firm with a view to building a Frazer Nash-Bristol. BMW’s former chief designer Fiedler acted as project consultant, but the Bristol-Aldington union was brief. AFN extricated itself due to different thinking, methodology and personality clashes. Although some Frazer Nash-Bristol literature was printed, AFN came away with an exclusive engine supply and the car became the first Bristol.

And this is it – the first Bristol, built in 1946. ‘Old Number One’ JHY 261 is one of four prototype 400s built prior to the 429 production cars. The 400 was almost a BMW greatest hits compilation: the 326’s 9ft 6in-wheelbase chassis; the M328 engine; and a coupé body that did a good impression of the 327 rather than being a precise copy of it. Only one 400 chassis was older, but that wasn’t built into a complete car and was destroyed long ago.

BAC kept JHY 261 for development. It also competed and crashed in the 1949 Coupe des Alpes Rallye with Elsie (‘Bill’) and Tommy Wisdom. It remained in company ownership until acquired by Bristol’s Tony Crook in 1992. Appropriately, Michael Barton – Crook’s biographer and a founding member of the Bristol Owners’ Heritage Trust – is JHY 261’s current owner, and only its third to date.

“Hugh Hunter, the Brooklands racing driver, was a protagonist of the Frazer Nash-BMW and he introduced Tony Crook to the 328,” explains Barton. “Crook then bought the ex-Betty Haig 328, EYW 3, which was the car she drove here at Brooklands to cover 100 miles in the hour in 1938. Crook was in the RAF when he happened to overhear Bristol inspection technicians talking about BAC’s plans to acquire the manufacturing rights to the pre-war BMW.

“Crook told the story of how he then hotfooted it down to Bristol – as an RAF officer he had access to petrol – and introduced himself to George White and team boss Vivian Selby. He was in business with Raymond Mays and Peter Berthon, as Raymond Mays & Partners Ltd, and the company came away with the very first Bristol distributorship in 1945. This was two years before Bristol had any cars for sale.”

Believed to have been painted in a soft RAF blue used for desert camouflage, this 400 was clumsily resprayed in the 1960s using a slightly brighter Fiat hue. The only other deviations from how it left Filton are its rally repairs and its 1947 1971cc Type 85 engine (replacing its original 1911cc ‘imperialised’ prototype ‘six’).

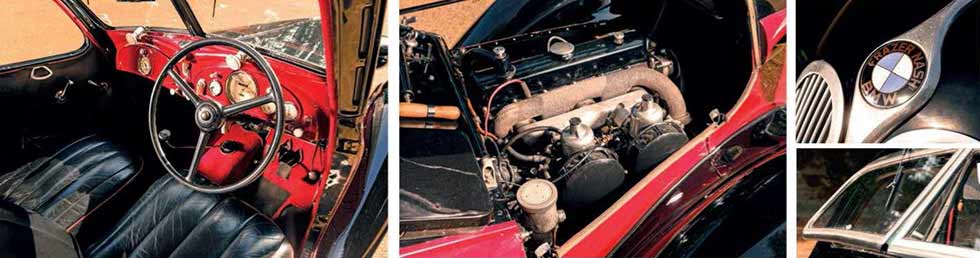

It’s chipped, cracked, weathered, worn and slightly moth-eaten, but this car not only – and unusually – still has its original direct-change, non-overdrive four-speed ’box with freewheel on first, plus unassisted drum brakes and non-cancelling trafficators, but has also deliberately never been restored. Its charm is intoxicating. You can spot the similarities, but compared with Dawes’ 326, the Filtonian appears more the pretty socialite to Eisenach’s comely hausfrau. Bristol’s expensive £2373 14s 6d close-coupled 95mph two-door saloon is obviously derived from the 327, but its dress sense shuns the 327’s baroque bonnet vents and detailing.

The £498 BMW, though, counters once you’re inside with more room, a wider pedal-box, wind-up windows, an opening split windscreen, clearer instrumentation and features such as self-cancelling indicators and a steering lock that some manufacturers failed to offer decades after the war. Even the fuel-filler cap and spare wheel are guarded by lock and key. In typical BMW fashion, the 326 slowly but surely grows on you.

Owned by Dawes for nine years, this February 1937 Frazer Nash-BMW was one of the first in the UK. “I don’t know as much of its history as I’d like to,” says Dawes. “It has been known in the club for many years, but unfortunately I don’t have all of its records. It’s one of about 10 326s currently known to the club in the UK, of which six are still complete. I do, though, have its AFN service records, which show that the car got some serious use before and during the war.

“It was restored by a BMW dealer, essentially as a showroom queen, 20 years ago. When I got the car, it looked like it does now – on the outside – but mechanically it was a bit of a heap of junk! When you get things such as a camshaft welded up, it’s not good… So over the years we’ve been doing what we can. Compared with other cars of its vintage, it’s an excellent grand tourer.”

We leave Brooklands and, because we’re in Surrey, the roads are busy. Yet the speed with which you acclimatise to these cars, and the way in which they handle today’s hustle and bustle, are perhaps the most astounding things about driving them. With 85bhp at 4500rpm, the 400 produces more power at higher revs than the BMW’s 50bhp at 3750rpm, but on these roads the difference doesn’t jump out at you. This might be because I’ve enjoyed far spicier Bristol ‘sixes’, or perhaps it’s because both engines are served by SUs. Non-original on the BMW and only briefly specified by Bristol, these carbs are better at doling out mid-range punch than venturing towards the outer limits of a rev range.

The Bristol has a stiffer throttle and its unassisted brakes require more muscle but make for easy heel-and-toe footwork. The BMW initially comes across as more user friendly: its cooler cabin has more room; its rack-and-pinion steering and brakes are lighter to use; and the Bosch self-cancelling indicators lessen the multi-tasking load. Having never been restored, the Bristol retains its wonderfully hewn-from-billet factory integrity. It fights back with a sharper, more positive gearchange, while JHY 261’s unique white wheel operates Bristol’s sublime steering rack – swift of turn-in and pure of feel. Held in place by its semi-bucket seat, the 400 is bliss to drive due to the quality of its manufacture and designer Jack Channer’s feel for a sizzling chassis.

The BMW’s four-speed, with freewheeling non-synchro first and second, takes longer to master. Despite the battle-torn road, the ride of both is good enough to cease pothole-spotting. Through all manner of bends, the 326’s light, positive steering does load up more and it rolls further than the Bristol, but here I have to stop and recalibrate. This is a pre-war car; it’s more than 80 years old. I’ve encountered cars far inferior to this that date from the late ’50s. As the quiet gearchanges materialise, you realise that this surprisingly – almost shockingly – usable car is an adept distance-coverer. Objectively, this BMW is right up there with the very best pre-war machines I’ve driven.

The 400, meanwhile, further cements its place in my affections. As we drive, my thoughts wander. It’s easy to appreciate why BAC continued with this formula – albeit enhanced – until 1960, and why Bristol, subsequently under Crook, continued to evolve the BMW design until production ended in 2011.

A memory from 2013 then emerges, from an interview I was fortunate to have with the late Syd Lovesy, a man who worked for Bristol Cars for more than 60 years. Amid his warm, gentle manner and natural modesty, the closest he came to a boast was when he ventured: “It’s true to say that the Bristol 400, the very first car we ever made, was the finest car in production at that particular time…”

It’s hard to think of a better way to endorse the wonderful design and intrinsic engineering quality of these magnificent cars.

Thanks to the owners, and to Richard Gatley and Paul Stewart at the Brooklands Museum (www.brooklandsmuseum.com)

‘Despite the battle-torn road, the ride of both is good enough to cease pothole-spotting’

FRAZER NASH AND BMW

Based in Isleworth, AFN Ltd was formed following HJ Aldington’s acquisition of Frazer Nash in 1927 and ‘chain-gang’ models such as the TT Replica and Nürburg enjoyed success in trials, hillclimbing and racing. Motorsport would be the arena that would have a sizeable influence on AFN’s direction, when at the 1934 Coupes des Alpes, the hitherto competitive Frazer Nash team was beaten by BMW 315s.

The six-cylinder sports car so impressed Aldington that he contacted BMW. By 19 November 1934, he had signed a contract turning Frazer Nash into BMW’s British concessionaire. Frazer Nash-BMWs would be sold alongside the firm’s existing range, and ultimately the right-hand-drive 315s, 319s, 320s, 326s, 327s and 328s would outsell total chain-gang production by a ratio of two-to-one.

Plans were made to build BMWs under licence and market them as Frazer Nash cars due to the hostility towards Germany after the Great War, but WW2 quashed any chance of this British-based manufacturing happening. Post-war, the chain-gang cars were history, as were plans for the Frazer Nash-Bristol, but BAC supplied AFN with Bristol FNS engines for its Fiedler-designed models including the High Speed/Competition, Le Mans Rep (below), Mille Miglia, Targa Florio and Sebring; production totalled just 84 cars.

Frazer Nash built its final model in 1957. Its relationship with BMW lasted until a falling out over the UK sales rights to the 1959 700.