Porsche Number 1. Driving the very first of many. In the beginning there was the Porsche 356-1 – mid-engined precursor of everything that followed. Andrew English drives it…

PORSCHE AT 70 THE ORIGINAL Driving the very first Porsche

You have to do a Walter Rohrl on the pedals,’ says Jan Heidak, engineer with Porsche’s museum. He ain’t kidding. With temperatures rising, this priceless car’s red oil-pressure warning light has become a constant companion.

The air-and-oil-cooled engine is heating up, which thins the oil, which reduces the oil pressure, which means you have to keep up the revs to keep up the oil pressure, which heats up the engine…

‘Porsche had experience of mid-engined cars with his Auto Union race designs – but it’s a packaging nightmare’

Add to this death spiral the clutch-pumping Bern traffic and the most precious and difficult gearbox in the Porsche canon (it’s unique), and this is the most nerve- wracking drive imaginable. ‘Don’t break it’ is one of the most oft-given pieces of advice. And I’m oft-reminded that Number One – the ‘first ever’ Porsche – will leave here for Porsche 70 displays in other parts of the world. Important ones. Yes, this is a big year for Porsche.

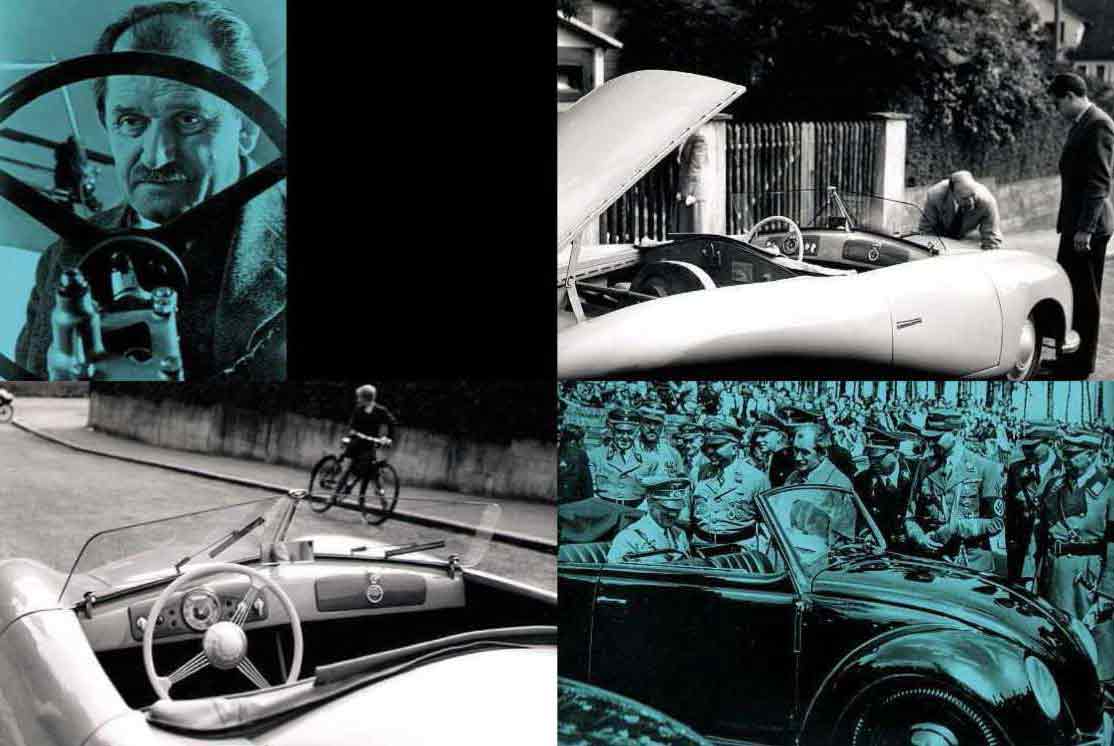

It’s 70 years since Ferdinand Porsche started building cars under his own name – although this is complicated because Number One was originally called VW Sport and there are also some who think that the first Porsche was actually the 1939 streamlined VW Tipo 64…

The man himself was largely a self-trained prodigy. In 1897 he joined carriage-maker Lohner from the electrical company that became Brown Boveri, where he trained and became a manager. At Lohner, Porsche’s precocious talent delivered the first-ever petrol/electric hybrid car; he then moved to Austro-Daimler, where he designed the streamlined 85hp Prince Henry, and then to Daimler as technical director, where he designed the Mercedes-Benz SSK.

After falling out with Daimler and being made redundant from Steyr, Porsche formed his own company in 1931, calling it (snappily) Dr. Ing. h.c. Ferdinand Porsche GmbH, Konstruktionsbu.ro fur Motoren- und Fahrzeugbau. It translates as ‘a design office for engine and motor-vehicle construction’.

There were three principal investors: Ferdinand, his son-in-law Anton Piech, and Adolf Rosenberger, the last two each contributing about 10% of the starting capital (3000 Reichsmarks), with Rosenberger as managing director and an establishment consisting of several of Ferdinand’s former colleagues, including Austrian engineer/designers Karl Rabe, Franz Xaver Reimspiess and Erwin Komenda, plus his son Ferry Porsche.

Few histories make mention of Rosenberger, but he was an important figure. A former works Mercedes driver, he more than once bailed out the company and he introduced Porsche to the management of Auto Union. He was a Jew in Nazi Germany, though, and, seeing the political direction of the Nazi party, he entrusted his shareholding to a friend, who helped him to escape the clutches of the Gestapo when he was arrested for ‘racial crimes’. He changed his name twice, at first emigrating to France, then Britain, representing Porsche in both countries. In 1939 he emigrated to the US, eventually taking citizenship.

At the end of World War Two, Porsche and Piech wrote him begging letters and he sent food and money. Yet when the Volkswagen plant was up and running and paying Porsche a handsome royalty for each Beetle sold, Rosenberger sued for a return of his assets and in 1950 received a derisory settlement that included a VW Beetle.

It’s an unedifying part of the Porsche legend, and there are others. Hans Ledwinka, for example, the brilliant Austrian engineer who designed the Tatra 97, which pioneered what became the VW Beetle’s backbone chassis, independent swing-axle suspension and rear-mounted, horizontally opposed, air-cooled engine. Porsche later admitted: ‘I might have looked over Ledwinka’s shoulder’, but in 1965 Volkswagen settled with Tatra out of court for (an alleged) one million Deutsche Marks.

None of this takes away from Porsche’s brilliance, but it confirms the fine edge of Ruhr-forged steel behind some of his business practices. Commissioned work for Porsche’s new company included a Wanderer saloon, the KUbelwagen, the Elefant Panzerjager tank, plus Hitler’s People’s Car – the Beetle – and the Type 64.

Not that Ferdinand had an easy war. He, Piech and Ferry were arrested in France when the French Government demanded that Porsche move his factory there as part of war reparations. When this was refused, they imprisoned Porsche senior and Piech for 22 months for Nazi collaboration. Ferry was released after six months and returned to his father’s company to build it up once again.

The firm had been moved out of Stuttgart to Gmund in Austria to avoid Allied bombing raids and Ferry had to organise work for his 200-strong firm; ‘engineers, metalworkers, welders, trimmers, all sorts,’ says Alexander Klein, manager of Porsche’s historic car collection. ‘He needed to get out and apply for work.’

Ferry Porsche applied his logic to the needs of the time: agricultural equipment, mowers, tractors, winches and water pumps were designed and built. Klein has studied Rabe’s diary, which gives the day-to-day life of the company in minute detail.

‘Rabe had also to organise the refurbishment of the company’s offices and workshops,’ says Klein, ‘and he had to report to the Allied powers about how the business was going. It’s incredibly detailed, right down to the type of wine they’d have with clients.’

Contract work with the Italian firm of Cisitalia for a Grand Prix car proved the key to Ferdinand Porsche’s release from French jail, with the Italian football player, race driver and businessman Piero Dusio fronting-up a kind of bail/ransom to release Porsche in order to repurpose his unraced supercharged 1.5-litre flat-12 Auto Union design as the Cisitalia 360.

Perhaps that’s what persuaded Porsche that he could make his own car, thinks Klein, the first mentions of the 356 are in Rabe’s diary entry for July 1947, including a tubular frame and mid-mounted, air-cooled VW engine, with the Beetle also supplying transmission, axles, steering, 16in wheels and drum brakes, the body on the 85in wheelbase was designed by Erwin Komenda.

And why the mid-engined configuration? Porsche had experience of mid-engined cars with his Auto Union race designs, and in pure handling terms a mid-engined configuration is a terrific solution – but it’s a packaging nightmare, That’s why Number One remains unique. As Klein points out, it took another 14 years for the first mid- engined production road car, the Bonnet Djet, to go into production.

‘Ergonomics were incredibly important to Porsche; how you sit in the car,’ says Klein, ‘there is the engine right behind the seats. It’s hot.’ I can confirm that, as the little engine is thrashing hot air into the bulkhead, which is heating the seats and making my back sweat, ‘there is also cabin space, which is much better with the rear-engined cars,’ says Klein. ‘Porsche wanted a two-plus-two layout for the production cars.’

Certainly your initial thought on jumping into Number One from the production 356 model is to wonder where all the space has gone, the sills are hugely wide, which is fine for strength, but they push the two passengers so close together that engaging the far-flung third gear inevitably means crunching your fingers into the passenger’s left knee; if only Porsche had been able to bring forward its Tiptronic and PDK’ boxes…

There is also the layout of the rear suspension, based on a ground-up redesign of the Type 64, the Type 114, which was a reversed Beetle arrangement, where trailing arms become leading arms, which can lead to some tail-happy moments. ‘It isn’t the most balanced system,’ admits Klein, although it’s difficult to be absolutely certain since Number One’s L-section Dunlops are already slipping on Bern’s tram tracks.

In fact, Ferry Porsche knew all this: in 1948 he and his father tested the unpainted Number One prototype on the roads round Gmund. Rabe’s diary shows that there were issues including deformation of the rear of the car and it’s an indication of the two Porsche’s misgivings about the configuration that the rear-engined 356 was already in development at that time.

‘We built that car only for experience,’ explained Ferry Porsche in 1984. ‘It was to see how light we could go and how many VW parts we would need.’

So we park the overheating Number One and wait, watching radiated heat fizzle into the Swiss mountain air. Switzerland has a close connection with Porsche’s car-making beginnings, most of the steel for this and the first 356 models having been sourced through the country. In July 1948, Number One made its debut at the Bern GP and journalists were invited to drive, including Robert Braunschweig from Automobil-Revue, which published the first road test.

That September, Porsche received an export licence, and in December, Number One became the first officially registered Porsche. It was supplied to Bernhard Blank, who rather through chance became a major investor in Porsche and the company’s first salesman and Swiss partner.

It was Blank who sold Number One to Zurich architect Peter Kaiser for CHF7500. It was also Blank who arranged for the Beutler coachworks to inspect Number One and successfully bid for the work building bodies for the first 356 models – 52 of them – in aluminium; subsequent cars had steel bodies. So when the first production rear- engined 356 was shown at the 1949 Geneva motor show, it was already sold, by Blank, to the aviatrix Jolantha Maria Tschudi. She paid CHF17,000 for the privilege.

But to Number One is where this year’s attention will be directed and, whatever misgivings there might be about the company’s formative years, it’s difficult not to like this tiny two-seater, even though it’s slow and hot. Despite its feather-like weight of only 585kg, with a mere 35bhp out of its 1131cc flat-four engine, you need to (carefully) work that gearbox and fourth gear is incredibly long, so on the Swiss mountains it’s rarely used. Despite reports at the time of incredible performance, quoted acceleration from rest to 62mph is 23 seconds and top speed is 84mph. On one road we have a Titanic battle with a small moped. It wins.

And while the ride is commendably good over the few bumps that manicured Swiss roads throw at us, the handling, with the vague steering and that weaselly back end, leaves much to be desired. Automobil-Revue observed that ‘the car is responsive and stable in tight curves’. Rather them than me.

Number One passed through several hands and was even fitted with a modern 1.5-litre engine and new brakes by Porsche for one owner. When Porsche bought it back in 1958 (swapped for a new 356 Speedster), its coachwork had been radically altered. Various attempts have been made to get it back to original condition, though Klein admits just which ‘original condition’ is the source of some debate; it’s currently finished in Boxster silver rather than the original grey.

So, while it might not be fantastically original, it is utterly authentic – and captivating, the simple dashboard with its central speedometer and the frameless windscreen are as pure as the designers intended, and Komendas touch on the bodywork is so light it takes your breath away, with just one line describing the front to the back – though the engine cover should be a one-piece panel rather than two.

Number One reminds me of what we’d all hoped Grant Larson’s 1993 Boxster concept would turn into when Porsche gave it the production go-ahead, only for it to be dumbed-down. Some might think that Porsches generally aren’t great-looking things, but this one, Number One, most assuredly is.

Even if its gearbox is terrible.

TECHNICAL DATA FILE SPECIFICATIONS 1948 Porsche 356 Number One

Engine 1131cc flat-four, air-cooled, mid-mounted, SOHC and one carburettor per bank

Max Power 35bhp @ 4000rpm

Max Torque 30lb ft @ 2200rpm

Transmission Four-speed manual transaxle behind engine, rear-wheel drive

Steering Worm and roller

Suspension Front: trailing arms, torsion bars, hydraulic dampers. Rear: leading arms, torsion bars, hydraulic dampers

Brakes Drums

Weight 585kg

Top speed 84mph

0-60mph 23sec

‘With a mere 35bhp from the 1131cc flat-four engine, we have a Titanic battle with a small moped. It wins’