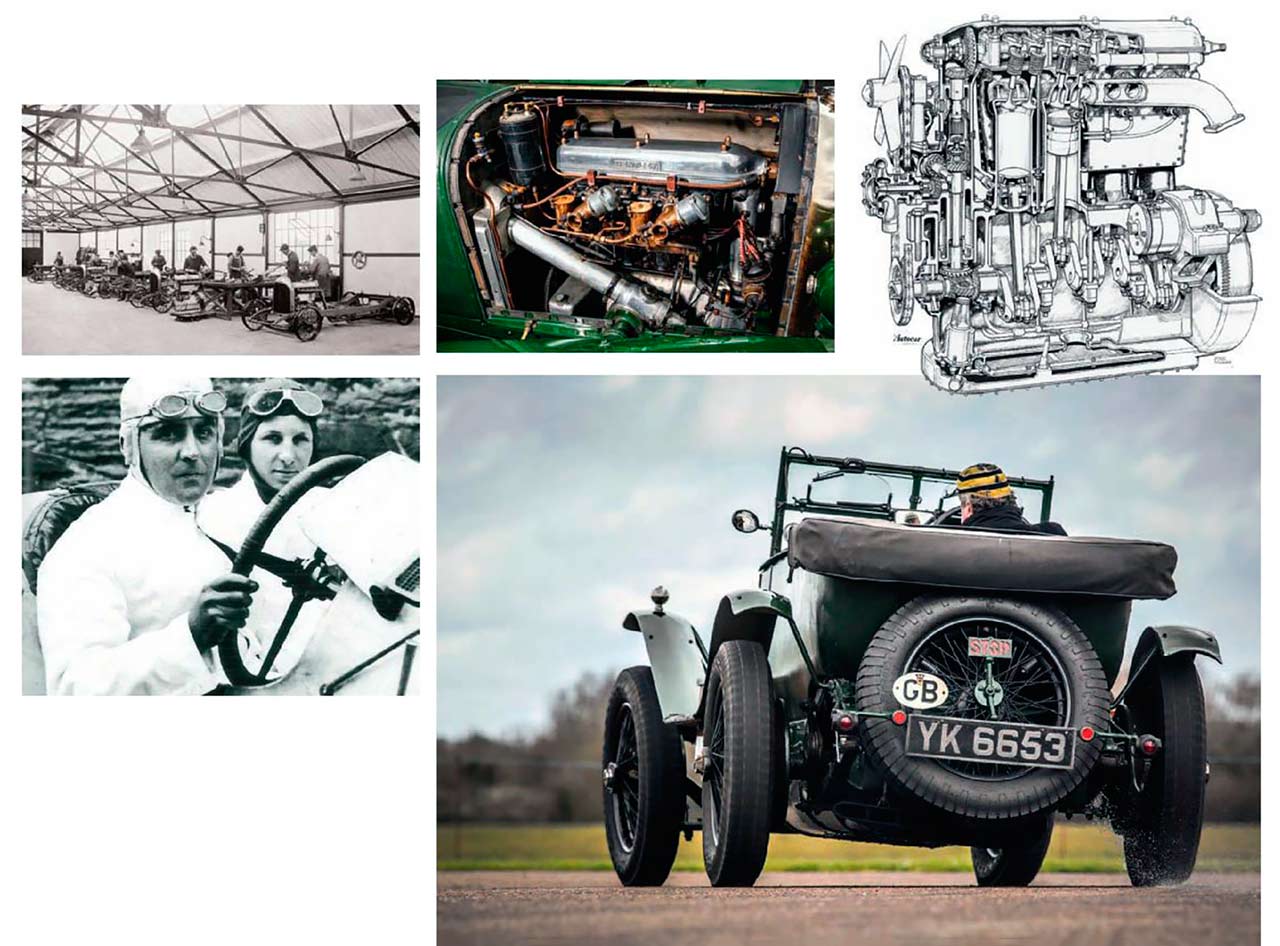

Bentley’s Famous Four. Four-cylinder Bentleys How the legend started. Bentley’s big ‘fours’. Driving the legendary 3 Litre and 4½. WO’s sporting and reliable four-cylinder cars gave the marque a flying start, says James Page as he samples the 3 and 4½-Litre Photography Tony Baker/LAT/Bentley.

Four-cylinder Bentleys

Bentley’s Cricklewood era lasted only 12 years, but that was long enough to establish a legend on which the modern company still trades. Throughout the 1920s, a line of exclusive, sporting road cars and a string of high-profile competition victories meant that the young firm soon earned its place alongside the likes of Vauxhall, Sunbeam and Lagonda.

During that successful but occasionally turbulent period, the backbone of the Bentley range was the four-cylinder engine with which the firm launched its first model, the fabled 3 Litre. Take into account the later 4½ variant, and this powerplant was fitted to 2342 out of the 3037 cars produced during the firm’s vintage years.

Rugged enough to twice win at Le Mans, and characterised by the famous ‘bloody thump’ that you feel as well as hear, the big ‘four’ was the brainchild of company founder Walter Owen. ‘WO’ was born in 1888 as the youngest of 10 children – his father had already retired by the time he arrived. His family’s money came mostly from his mother’s side, and he was raised in the comfortable surroundings of St John’s Wood. WO followed his brothers to Lambrook prep school in Ascot, then Clifton College in Bristol.

A diligent but unremarkable student, he later abandoned a course in engineering theory at King’s College to take up an apprenticeship at the Great North Railway in Doncaster.

In 1912, he and his brother Horace Milner – or ‘HM’ – bought into, and later took over, Lecoq and Fernie. The business imported Buchet, La Licorne and DFP cars, but concentrated on only the last of those when it was renamed Bentley and Bentley. WO adapted a 12/40hp for his own competition use, and hit upon the idea of using aluminium pistons in an engine that also gained twin plugs per cylinder operated by twin magnetos – ideas that he would revisit when he formed his own company.

During World War One, his knowledge of aluminium pistons was applied to aircraft engines. Both Rolls-Royce and Sunbeam adopted them, but he had trouble convincing Gwynnes, which made Clerget engines under licence. The Clerget was fitted to a number of aircraft, but its failures were causing an increasing amount of crashes on the Western Front.

Gwynnes did eventually relent and adopt the aluminium pistons, but a frustrated WO had already drawn up his own rotary engine. The BR1 was fitted to aircraft including the Sopwith Camel, while the BR2 of 1918 produced twice as much power as the earlier Clerget.

After a degree of campaigning to a reluctant Treasury, WO was awarded an £8000 grant by the Royal Commission at the end of the war in recognition of his efforts. Bentley and Bentley had continued to trade – thanks largely to the efforts of Geoffrey de Freville, later of Alvis – but WO’s thoughts had already turned away from importing DFPs towards building a car.

Glance at a list of UK manufacturers that were around in the years immediately after the war, and you could conclude that this was a booming period for car ownership. So it was, but this was also a time of rapid social and economic change. Few of those companies survived the 1920s – in their original form, at least. Countless smaller marques came and went, and even established names struggled. Napier stopped making cars in 1924, while Vauxhall might have done likewise but for the intervention of General Motors.

WO, however, wouldn’t be deterred. During the war, he’d discussed a design with Humber’s Fred Burgess, who turned his concept into drawings. Bentley Motors was formed in January 1919 and took offices in Conduit Street, which enabled WO and Burgess – plus Harry Varley, formerly of Vauxhall – to start work in earnest.

Their first car was put together in a small building in London’s New Street Mews. When they fired it up, a nurse from a nearby care home dashed round to complain that the noise was disturbing her patients. Fittingly, and despite the fact that their activities clearly upset the neighbours, a blue plaque marks this historic spot on what is now Chagford Street.

The model that they’d devised used a chassis with channel-section side members that swept up and over beam axles. The engine was of monobloc construction, and featured four valves per cylinder that were operated by an overhead camshaft. That, in turn, was driven by a vertical shaft that came up from the crank and included a take-off for the twin magnetos. Aluminium pistons were used, of course.

To save costs, some shareholders wanted to ship out the building of production cars, but WO resisted. He began to look around for a factory site, and settled on Oxgate Lane in Cricklewood. At the time, this was farmland; now, it nestles alongside Staples Corner, near where the M1 motorway begins.

Customer cars would not start leaving Cricklewood until 1921, but in January 1920 The Autocar helped to maintain interest by publishing a romantically lyrical account of a test ride aboard the first prototype, EXP1: ‘The roar of the exhaust rose to its full song. To such an accompaniment the pulse beats quicker… Every part of one’s being urges greater speed in the fierce wild intoxication of a moment supreme above all others in the life sensations of man.’

For five years, the 3 Litre would remain Bentley’s sole product, but it was updated along the way. Introduced with a 9ft 9½in wheelbase, a longer chassis (10ft 10in) was also offered from ’22, along with a B-type gearbox that had wider ratios. A year later, front brakes were fitted – having considered a hydraulic system, WO decided upon rods. The Speed model, with twin SU ‘sloper’ carburettors, came along in 1924, while the Supersports – which had a 9ft wheelbase, 6:1 compression ratio and was guaranteed to do 100mph – was introduced in ’1925.

By the time that the 4½ Litre was being considered, the Bentley landscape had changed. Perennially short of funds, matters had come to a head at the end of 1925 – to the extent than HM was personally helping to meet the wage bill. WO approached Morris to see if it would be interested in taking a share, but to no avail.

Enter Woolf Barnato. A fast and reliable racing driver, fine cricketer, scratch golfer and heavyweight boxer, the immensely wealthy 31 year old was a tough businessman who was well aware of Bentley’s parlous state. He came on board as chairman, made WO managing director and saved the company from going under.

A new London showroom was opened in Pollen House, with Barnato’s offices upstairs.

Even after Barnato had taken over, though, WO often walked slowly around the works. With tongue firmly in cheek, older hands would tell the apprentices that if he saw you doing anything wrong, he would stare at you and you’d never grow any taller. If you were doing something particularly bad, he’d remove his pipe from his mouth and look at you, and you’d shrivel up.

On one occasion, so the legend went, he’d seen an apprentice put a mug of tea on the machined surface of an engine block. WO stopped, took out his pipe and actually spoke. The apprentice disappeared and was never seen again… Even into 1927, the elderly 3 Litre was still the focus of Bentley’s racing efforts, but that year Barnato had entered Le Mans with Old Mother Gun, the prototype 4½ Litre. That car’s ‘four’ wasn’t simply an enlarged version of WO’s original powerplant, though. It shared a bore (100mm) and stroke (140mm) with the recently introduced 6½ Litre’s inline-six, and was therefore able to use that car’s conrods and pistons.

If the 3 Litre had been showing its age against roadgoing rivals from the likes of Sunbeam, the new model levelled the playing field. A handful were built on the earlier car’s shorter chassis but the vast majority used the 10ft 10in wheelbase, and the 4½ was again offered with a wide range of body styles. Our featured example – which has been in the same ownership since the early 1970s – sports handsome Freestone & Webb two-seater, drophead-coupé coachwork.

The right-hand gearchange dictates that the inexperienced are better off entering from the passenger side if they’re to avoid getting the lever up their trouser leg. Pull out the magneto switches, prod the starter and the big ‘four’ rumbles into life with a purposeful bass note that goes right through you when you blip the central throttle. Heavy at low speed, the steering never exactly lightens up, but it’s spectacularly direct.

Bentley gearboxes carry with them a fearsome reputation, but this 4½ is equipped with the close-ratio D-type unit, which is an absolute delight and a lot easier to use than ‘our’ 3 Litre’s slower B-type. The only slightly awkward aspect is that the gap between the clutch and brake pedals on the later car is only just big enough for your foot to reach the diminutive throttle pedal. As is to be expected, the 4½ is the quicker of the two off the mark – it feels broadly comparable to Vauxhall’s impressive 30-98 – but once both are up to speed the difference is less noticeable.

The 3 Litre shares the 4½’s quick steering, and can be thrown into corners with abandon, enabling you to carry more speed towards the apex than you’d expect. As its owner, Philip Strickland, later demonstrates with impressive expertise, it can then easily be coaxed into a gentle slide as you power through.

“It’s an amazing bit of kit to race,” he enthuses. “I drove a 4½ Litre at Goodwood and reckon that this is quicker through corners. You can fling it around. They all understeer, but it behaves well. It’s very predictable.”

Both cars boast huge reserves of torque, with third gear pulling from almost a standstill. In fact, our short test track can be negotiated in that ratio alone, all the while accompanied by that wonderful exhaust note. Even though both models are imposing and full of purpose when standing still, it’s the big ‘four’ that provides them with their heart and soul.

“It’s just a really good engine!” says vintage- Bentley specialist Ewan Getley. “It’s strong, and breathes incredibly well. Bentley was a very clever engineer, though. His modified Clerget aero engines were doing 70 hours between overhauls; the factory units did only 15 hours.”

Contrary to popular assumption, Bentley was always working hard to save weight, too. The firm started using Elektron instead of aluminium in some of the castings because it was lighter and stronger. The more adventurous workers discovered that you could set light to the filings as they fell. Someone then overdid it and got burned, which put an end to such tomfoolery.

“People try to modify them but it doesn’t work,” continues Getley. “These days, we use materials that might be better than in period, but otherwise owners want to keep them original. I’ve always found that it’s the non-standard things that cause trouble. My racer is running a higher compression ratio but it’s still on its standard camshaft and gearbox.

“The centre main bearing can break up, but that’s helped by using a counterbalanced crank and it’s the only real weakness. If you look after them, they’ll just keep going and going.”

Strickland would certainly agree with that. He bought his 3 Litre nearly 40 years ago, races it all over Europe and has twice driven it across India – not to mention from Siberia back to the UK, and from Brooklands to Red Square. He works on the Bentley himself, and knows it inside-out: “It’s an engineer’s car. Everything comes apart and goes back together really easily. This one still has its original crank, rods and camshaft, and we think it’s the only 3 Litre still running hourglass pistons. They’re a work of art.”

Sadly, the harsh economic realities caused by the 1929 Wall Street Crash and subsequent Depression could not be ignored. Two six-cylinder models made late appearances: the mighty 8 Litre was the right car but at emphatically the wrong time, and the 4 Litre a misguided attempt to produce a rival to the Rolls-Royce 20/25hp.

It wasn’t enough. Despite the fact that, as The Autocar put it, ‘Few firms in the world have acquired so famous a name in so comparatively short a time,’ Bentley ceased trading on 11 July 1931. Barnato sent everyone on the staff an extra month’s salary – workers received a week’s pay – and the Cricklewood factory shut, never to reopen. When the Bentley name reappeared two years later, it was under the ownership of Rolls-Royce and the cars were being made in Derby – but that’s another story altogether.

Thanks to Duncan Wiltshire and Georgina Cook at the Flywheel Festival. For tickets, call 01728 684410 or see www.flywheelfestival.com

‘WHEN THEY FIRED IT UP, A NURSE CAME ROUND TO COMPLAIN ABOUT IT DISTURBING PATIENTS’

‘BENTLEY GEARBOXES CARRY A FEARSOME REPUTATION, BUT THIS D-TYPE IS A DELIGHT’

‘CONTRARY TO POPULAR ASSUMPTION, BENTLEY WAS ALWAYS WORKING HARD TO SAVE WEIGHT’

TECHNICAL DATA FILE SPECIFICATIONS BENTLEY 3 LITRE

Sold/number built 1921-’1929/1622

Construction pressed-steel ladder frame with choice of coachwork

Engine iron block and head, alloy crankcase, overhead-camshaft, 16-valve 2996cc ‘four’, single Smiths/Claudel-Hobson carburetor or twin SUs, twin magneto ignition

Max power 85bhp (est)

Max torque n/a

Transmission four-speed manual, driving rear wheels via cone clutch

Suspension: front beam axle rear live axle; semi-elliptic springs, friction dampers

Steering worm and wheel

Brakes mechanically operated drums (rear only until 1923)

Length 12ft 5in-14ft 3in (3785-4345mm)

Width 5ft 8 ½ in (1740mm)

Wheelbase 9ft 9 ½ in-10ft 10in (2743- 4345mm, plus Supersports on 9ft chassis)

Weight 2688-3916lb (1222-1780kg)

Max speed c80mph

Price new £1050 (chassis only, 1923)

Price now £175,000+

TECHNICAL DATA FILE SPECIFICATIONS BENTLEY 4 ½ LITRE

Sold/number built 1927-’1931/665 (plus 50 supercharged variants)

Construction pressed-steel ladder frame with choice of coachwork

Engine iron block and head, alloy crankcase, overhead-camshaft, 16-valve 4398cc ‘four’, twin SUs, twin magneto ignition

Max power 105-110bhp (est)

Max torque n/a

Transmission four-speed manual, driving rear wheels through plate clutch (from ’1929)

Suspension: front beam axle rear live axle; semi-elliptic springs, friction dampers

Steering worm and sector

Brakes mechanically operated drums

Length 12ft 5in-14ft 3in (3785-4345mm)

Width 5ft 8 ½ in (1740mm)

Wheelbase 10ft 10in (4345mm, plus nine cars built on the 9ft 9 ½ in chassis)

Weight 3640lb (1651kg)

Top speed c90mph

Mpg 15

Price new £1050 (1927, chassis)

Price now £200,000+

The ‘Blower’

After Woolf Barnato took over at Bentley, WO was still heavily involved with the race team, which was based a couple of miles down the road from Cricklewood, at Kingsbury. It was competition that provided the motivation for works driver Sir Henry ‘Tim’ Birkin to suggest a supercharged version of the 4 ½ Litre. WO wasn’t a fan – “[It] was against all my engineering principles” – but Barnato gave the go-ahead for 50 road cars to be built (below).

Amherst Villiers designed the blower unit itself and the Hon Dorothy Paget provided the money, but, although fast, it wasn’t as reliable as the unblown cars and didn’t deliver the racing success for which Birkin had hoped. He did, however, drive a stripped version to second place in the 1930 French Grand Prix – run that year to Formule Libre regulations – and lapped Brooklands at almost 138mph in his monoposto-bodied version.