Group В Legends. Rallying madness – in roadgoing form – the ultimate supergroup. In the mid-1980s, Group В of the World Rally Championship inspired the wildest, most powerful rally cars ever built. Mark Dixon charts the rise and fall of Group B, and looks at five of the ‘homologation specials’ sold to the public. Photography: Matthew Howell.

The cloth cap brigade will tell you that motor sport was at its most exciting in the 1950s and ’60s – the days before full-face helmets, old boy, when you could see a driver’s face as he drifted his open-wheeler around Goodwood or Silverstone, and then have a quick chinwag in the paddock afterwards.

Well, that may be so, but there’s another generation for whom motor sport reached its peak 20 or more years later. The 1980s were the era of excess all areas, and motor sport was no exception. These were the years in which a Le Mans car could top 250mph down the Hunaudieres straight, in its pre-chicane glory days; when turbocharged F1 engines struggled to contain 1500bhp power outputs (and frequently didn’t); and when bespoilered Touring Cars spat flames from their exhausts as they rubbed arches and swapped lairy paint at intoxicating race speeds.

And then there was Group B.

Group B: a phrase so apparently mundane, and yet so evocative for anyone who ever stood and shivered on a muddy forest stage, circa 1985-1986. Group B: the Fight Club of rallying; a no-holds-barred battle to the death. Literally so, on too many occasions.

GROUP В CARS

It was never meant to be like that. In 1982, when international rallying’s governing body FISA – the Federation International du Sport Automobile – was drawing up the regulations for a new set of rally car classes, it had no idea it was about to unleash a kind of automotive arms race between manufacturers. But that’s exactly what happened.

Since the mid-’60s the majority of rally cars had been divided into four classes, known as Groups 1 , 2, 3 and 4. The first three hadn’t given the authorities any trouble: they were for standard or modified saloon and GT cars. But Group 4 was more problematic. By the late ’70s, manufacturers were producing seriously hot versions of what were supposedly family saloons for Group 4, and running rings around the supposedly more sporty GT cars in the lower groups.

So FISA, under the autocratic leadership of president Jean-Marie Balestre, decided to rewrite the infamous technical Appendix J of the rule book. After much political wrangling between FISA and the car manufacturers, three new classes were agreed on: Groups A, B and N.

Group N (for Nationale, because it was aimed at privateers running in national events) was basically for showroom-stock rally cars. Group A was for modified touring cars, with a minimum production of 5000 vehicles in standard form. Group В was more of a free-for-all. Only 200 cars had to be manufactured and engines could be normally aspirated or turbocharged – but, if the latter, a multiplying factor of 1.4 was applied to their capacity, and that figure governed the weight they had to run to.

What’s more, once your 200 homologation cars were up and running, you could add a further 20 ‘evolution’ models, and do the same thing every 12 months after that. There were also no restrictions on how you got the power down. And there was the rub… When the four-wheel-drive Audi quattro blasted onto the rally scene in 1981, it changed things forever. The benefit of sending power to all four wheels on a slippery surface gave the quattro a time advantage on special stages that was measured in minutes rather than seconds.

Change couldn’t happen overnight, however, so, when Group В came into existence in mid- 1982, most of the early Group В rally cars were still two-wheel drive: either existing Group 4 cars that were re-homologated for Group B, or new designs that had already been on the drawing board. Some of those, like the Lancia 037, gave the quattros a run for their money, particularly on fast tarmac events where four-wheel-drive was less of an advantage. But then Peugeot came up with the four-wheel-drive, mid/rear-engined 205T16, a car that really exploited the opportunities offered by Group B. The arms race was on.

Battle was properly joined at the start of 1986, on the Monte Carlo Rally. For the first time the 4WD rally supercars appeared in force: Audi Sport quattro E2, Peugeot 205T16E2, Lancia Delta S4, Austin Rover’s MG Metro 6R4 and Citroen BX4TC. Only Ford was late for the show, because it missed out on homologating its new RS200 by days. This new turbo 4WD era of rallying was thrilling stuff, and the spectators loved the unprecedented speed it brought. Some of them, however, could not control their enthusiasm – and the rally organisers proved quite unable to control them. As the 500bhp missiles hurtled along twisty, often bumpy tracks, spectators would idiotically line the outside of corners, or even gather on the road itself before leaping out of the way at the last possible moment. It was macho stupidity and there was only one possible outcome.

On 5 March 1986, RS200 driver Joaquim Santos went off-line trying to avoid spectators and crashed into the crowd. At least four people died and many more were badly injured. Two months later, on the Tour de Corse, rally ace Henri Toivonen and his co-driver Sergio Cresto died when their Lancia Delta S4 left the road and caught fire – although no spectators were involved. Shortly afterwards, on the Hessen Rally in Germany, co-driver Mark Wyder also burned to death when Swiss driver Marc Surer’s RS200 hit a tree sideways. Group В was finished. While some argued that accidents could happen at any speed, and that better crowd control and in-car safety systems – notably fire retardation – were more sensible options, their voices were drowned out in the rush by FISA to be seen to be taking action. It banned Group В with effect from 1 January 1987. At the same time it scrapped a proposed new Group S. which would have limited power outputs to 300bhp while allowing car makers to carry on experimenting with ‘free’ mechanical configurations.

That left a lot of very expensive and nearly new Group В machinery struggling to find outlets for its abilities. Peugeot modified its 205T16 and did well on the Paris-Dakar, Metro 6R4s were allowed to run in Clubman or restricted form on British national rallies, and cars like the Audi Sport quattro E2 had moments of fame at places such as the Pikes Peak hillclimb.

But as their usefulness dropped, so did values, and it wasn’t until the late 1990s, when German photographer Reinhard Klein set up the original Slowly Sideways club for owners of former Group В cars, that interest in them started to perk up. It’s been growing steadily ever since and these formidable rally weapons now regularly thrill the crowds whenever they’re demonstrated at classic car events such as the Goodwood Festival of Speed.

Ironically, today it’s generally easier to find rally-spec versions of old Group В cars than the plain Jane road-going models built for homologation purposes. So, never ones to take the easy option, we brought five of the road cars together at an appropriately off-road location. We start with the Peugeot 205T16, over the page.

‘The spectators Loved it, but some were unable to control their enthusiasm – and the rally organisers proved quite unable to control them.’

Right Lancia’s successor to its 2WD 037 was the 4WD Delta S4, here on the 1986 San Remo in the hands of Markku Alen.

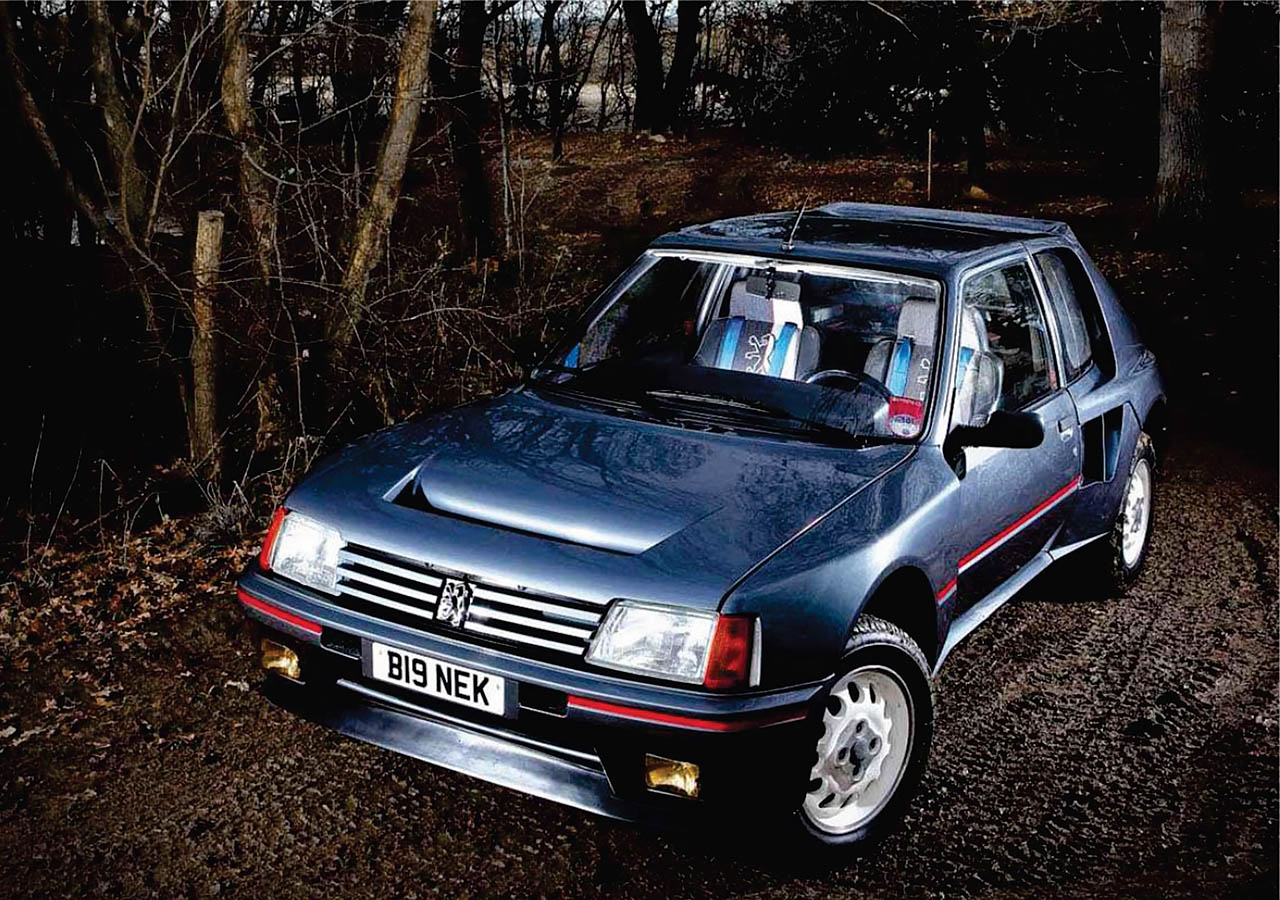

Peugeot 205T16

Forget the quattro. The 205T16 is the car that defined Group B, at least in the early days. It’s still regarded as one of the finest rally cars ever built.

Peugeot, under the direction of motor sport director Jean Todt, started with a clean sheet of paper for the 205T16. Ironically, though, the result didn’t look too far removed from a bog-standard 205 – a deliberate policy to drive punters into the showrooms, since the 205 had yet to be launched when the T16 was being planned.

There was another similarity, too. The T16’s 1775cc turbo engine – which gave 350bhp in rally spec, and an incredible 500bhp in ultimate E2 rally form – was based on the bottom end of the 205 diesel that would prove so popular with economy- minded commuters during the 1980s.

T16 road cars, like Ian Kirkwood’s example above, were detuned to a ‘mere’ 200bhp, giving a claimed 0-60mph time of 6.0sec and a top speed of 130mph. Quick enough, but no match for a Porsche 911 Carrera – even though, with a UK retail price of £26,999 in 1985, the T16 was £3200 more expensive than the Carrera, and only two grand less than a Ferrari 3086TB.

That’s why, reckons Ian, Peugeot struggled to sell the 200 roadgoing T16s it was obliged to make to meet homologation requirements – his car is number 188-with maybe half-a- dozen of the UK-allocated T16s going straight into the dealer network as promotional vehicles. Apparently, Kodak bought one and painted it yellow for just this purpose. As built, all T16 road cars were metallic grey, and all were left-hand drive.

Inside, the T16 is relatively civilised, with full carpeting and even electric windows. It fires up instantly thanks to Bosch fuel injection, idling with a pleasantly thrummy noise, and is easy to shunt around at low speeds, displaying none of the temperament for which its highly strung rally cousins were notorious. The road-car engine seems to be pretty reliable; if there’s a weak point it’s the overly complex electrical wiring.

Roger Bell road-tested the first UK import (bought by a Nottinghamshire Peugeot dealer) for Car magazine in 1985. He loved its crushing performance on local B-roads: ‘Convoys of coal trucks, scurrying from pit to post, were easy prey for the potent Pug… It would leapfrog them in threes, with a searing blast through the intermediates. You have to work at it, mind, to keep the lag-prone turbo on song, but it’s no chore to wring from the engine its fiery best.’

He was less convinced by the T16’s allround ability as a car to live with, judging that its brick-like aerodynamics conspired against it as a high-speed cruiser. The Audi quattro and the 911 made better sense for motorway work, he reckoned, ‘…but the Peugeot’s handling and roadholding are light-years on from those of the tricky Porsche.’

Ian Kirkwood concurs that the T16 is not a great long-distance car. ‘The most I’ve done in a day is 200 miles, and I ended up on the back of a recovery truck because the fuel pump failed. But interest in Group В cars is growing all the time – and the T16 holds special memories for me, because I worked for Peugeot when they were new and remember seeing them in the showrooms.’

‘Roger Bell road-tested the first UK import for Car magazine in 1985. He loved its crushing performance on Nottinghamshire В-roads’

Above T16 road car’s scuttle, windscreen and steel doors are regular 205, giving it a strong 205 family ‘look

Right and below Typically angular ’80s Peugeot cabin has slock 205 wheel; engine is based on 1.8-litre diesel block.

RALLYING THE 205T16

The 205TI4 was one of the first Group В supercars, and also one of the most enduring. In its E2 ‘second evolution’ incarnation, distinguished by a rear-mounted wing and aerodynamic tabs on the front spoiler, it was putting out a claimed 500bhp – although some reckoned the true figure was north of 600bhp.

The brainchild of newly appointed Peugeot Talbot Sport director Jean Todt, the original 205T14 had a 370bhp, 1775cc turbo engine driving through a modified Citroen SM gearbox. It was unveiled just one week after the launch of the showroom 205 in February 1983.

Early WRC outings on the 1984 Tour de Corse and Acropolis Rally were exciting but ultimately frustrating, and it was on the 1000 Lakes Rally in Finland that the T14 finally came good. Ari Vatanen blew the Lancia 037s and Audi quattros into the weeds, setting fastest times on 31 of the 50 special stages, and winning the event outright.

It was a pattern that was repeated on the 1984 RAC and into 1985. Vatanen and the T14 were minutes faster than the previously all-conquering quattros – in other words, minutes faster than drivers such as Mikkola and Rohrt – resulting in the Manufacturers’ title for Peugeot in 1985, and the Drivers’ title for its works pilot Timo Salonen.

For 1984, Salonen and fellow driver Bruno Saby were joined by Juha Kankkunen, freshly poached from Toyota. The three works T14 E2s put in a good showing on the 1984 Monte Cario – 2nd, 5th and 4th – but yielded victory to Lancia’s new Delta S4. The duelling between Peugeot and Lancia for 1st and 2nd would be repeated throughout 1984, the two teams regularly swapping places on the leader boards. Peugeot took six wins in total while Lancia achieved four.

Kankunnen secured the Drivers’ title for 1984, while Peugeot was Manufacturers’ Champion for a second year. The end of Group В didn’t spell the end of the TI 4’s competition career, however.

Modified with a longer chassis so it could carry more fuel, and with uprated doubledamper suspension, the T14 went on to win the Paris-Dakar in 1987 and 1988.

Thanks to Drive-My 205 Peugeot Club

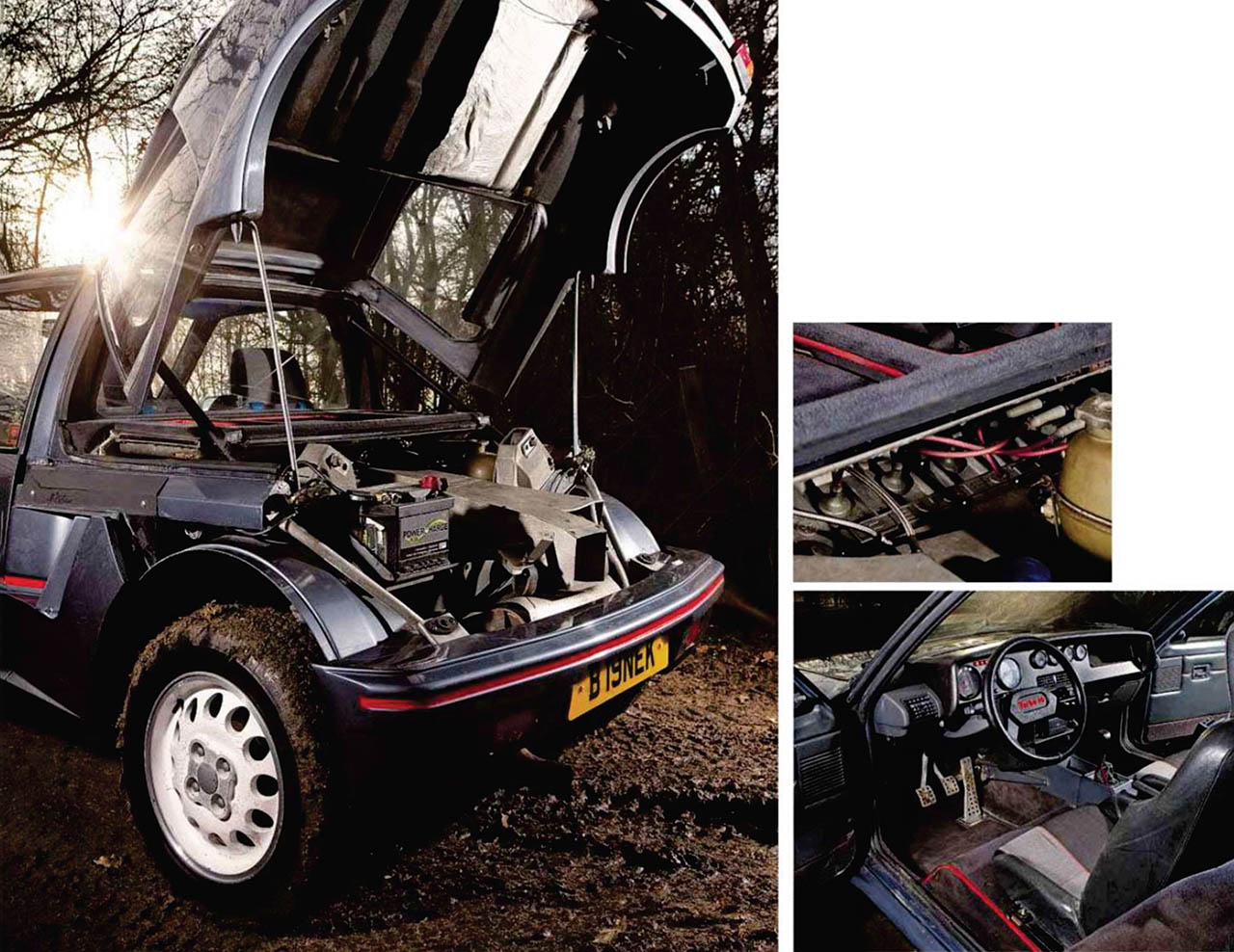

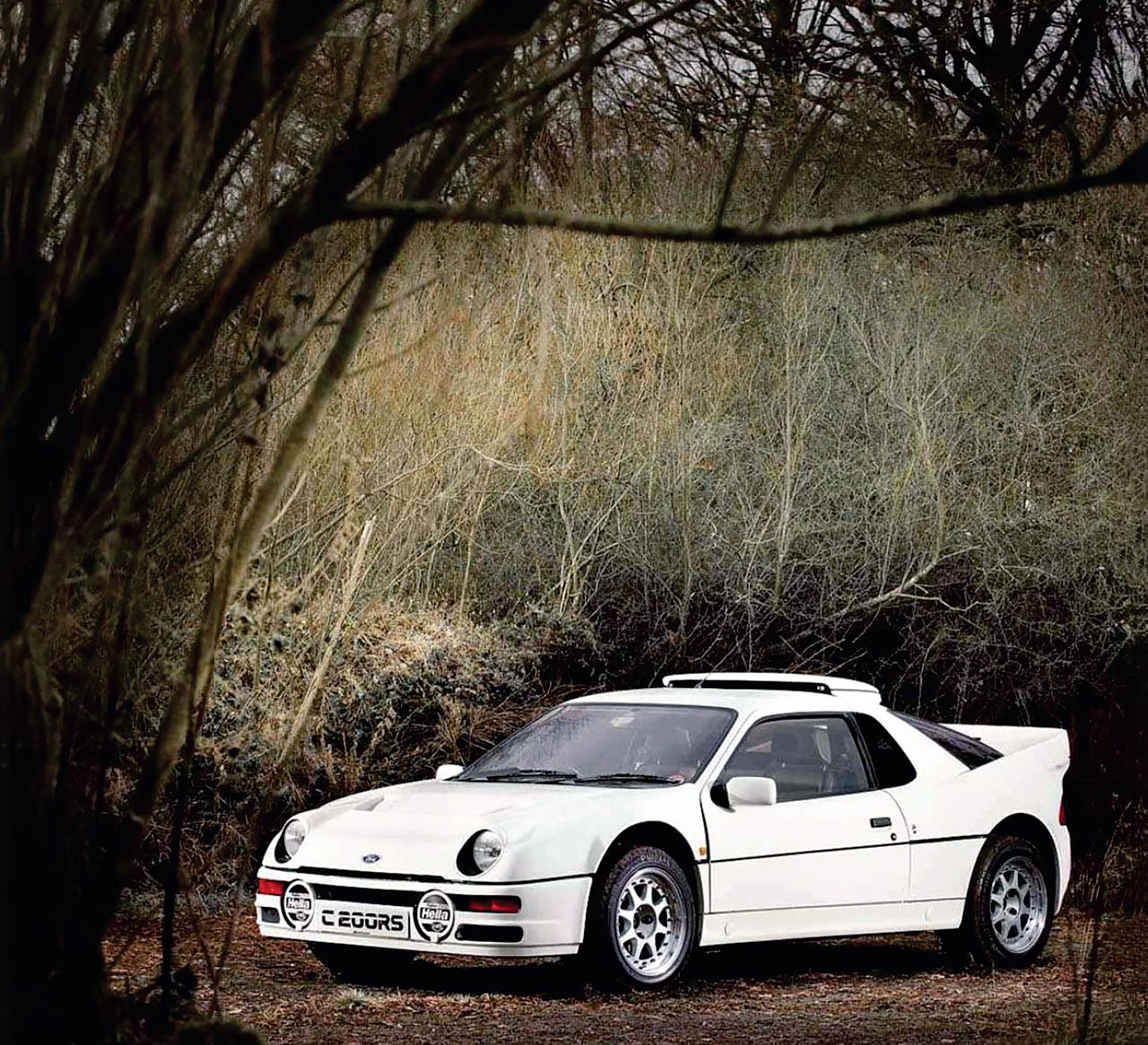

Ford RS200

Of the five cars here, the RS200 is the only one that makes no attempt to look even vaguely like something the man in the street could buy in ‘cooking’ form from his local dealer. In fact, there are a few shared components with the Sierra – windscreen and door frames – but the RS200 was a car apart: a tool built to win rallies, and hang the expense.

And it was an expensive car even in relatively soft 250bhp road trim. Retail price in late 1985 was a fiver under £50,000 – admittedly, probably half what each car cost Ford to make, but even so…

The RS200 conformed to the Group В template laid down by Peugeot’s 205T16: mid-mounted engine and four-wheel drive, although in the Ford’s case its 1804cc Cosworth BDT four-pot was aligned longitudinally, driving a front-mounted gearbox that sent drive to both ends. In fact the RS200 had selectable four-wheel drive: the pilot could choose between RWD only, 4WD with a 37:63 front:rear torque split or, for really difficult surfaces, a 50:50 torque split by locking the centre differential. Front and rear diffs were of the viscous-control type, as per Sierra and Granada 4x4s.

The Ghia-styled body consisted of GRP panels over a steel/carbonfibre/aluminium central tub, and was built by Reliant at its Shenstone factory. Six prototypes and 194 production cars were made, to meet the homologation requirements exactly – at least, parts for the 194 production cars were made, but it now seems that 52 of those cars were either never completed or were stripped for spares after the Group В ban took effect in 1986. Ford actually built (eventually) a couple of dozen 600bhp evolution versions but they were too late to appear on a WRC event; Stig Blomqvist set a 0-100km/h Guinness World Record of 3.07 seconds in an RS200E, though.

Most of the road-spec cars will have been bought as ‘trophy’ collectables when new – our feature car, now owned by enthusiast Mark Boulton, is reputed to have adorned the foyer of a Northampton nightclub – but a few were used intensively as part of Ford’s endurance testing. Motoring historian Graham Robson was under contract to Boreham at the time for various PR duties and covered an incredible 80,000-plus miles in a succession of four RS200s – ‘Even now, whenever I get stuck in a traffic jam, I think “Thank God I’m not in an RS200”,’ he jokes.

Few people, then, are as well-placed as Graham to sum up the RS200 as a road car. It was quite well equipped – electric windows and a radio-cassette were optional – and the ride was supple, but it was noisy and undeveloped in areas that had no relevance to rallying. Graham remembers the heater as being particularly poor.

The running gear wasn’t bulletproof, either, when subjected to the rigours of daily commuting. ‘My colleague Bob Howe popped two engines because of overheating in traffic jams, and I broke another when a cambelt failed,’ recalls Graham. ‘I also suffered catastrophic gearbox failure due to a seized mainshaft bearing. But it was a fabulous car to drive in the right conditions. It didn’t handle, as such – you just pointed it where you wanted to go, and it went.’

Standard finish was Diamond White but a few RS200s were subsequently painted blue, black and red after Group В was axed and Ford suddenly needed to shift a number of unsold cars. Graham’s last RS200 was a red example and he tried to buy it from Ford when his loan period was up. ‘Unfortunately they wanted full list price, which was 50 grand, for a car with 48,000 miles on it, so that was the end of that!’

Above and right RS200 was designed with switchablc 2/4WD, selected by red knob; twincoil suspension aided notably supple ride.

‘My colleague Bob Howe popped two engines because of overheating in traffic jams, and I broke another when a cambelt failed’ – GRAHAM ROBSON‘

RALLYING THE RS200

The RS200 grew out of Ford’s aborted RWD RS1700T rally car (see page 56), a FWD Escort-based machine that had been conceived for Group В before it became apparent that four-wheel drive and more horsepower were the keys to success.

Ford’s European motor sport boss, Stuart Turner, pushed the RS200 project through. It was designed by F1 engineer Tony Southgate and ex-Porsche man John Wheeler, with body styling by the Ford-owned Ghia studios. Delays in building enough cars for homologation meant that the RS200 missed out on the 1985 WRC season, but Malcolm Wilson took victory on its debut outing, the Lindisfame National Rally, in August 1985.

Homologation finally came through for 1 February, 1986, in time for Ford to enter a pair of RS200s in the Swedish Rally, where Kalle Grundel’s car finished third overall; the sister car driven by Stig Blomqvist retired with engine trouble. That third place was to be the high point of the RS200’s short Group В career.

On the next WRC event, the Portuguese Rally, tragedy struck when the RS200 of local hero Joaquim Santos crested a blind right-hander to find spectators in the road; in trying to avoid them, he lost his line, skidded on loose sand and hit another bunch of spectators lining the next bend. At least four people died – the true figure was never revealed – and many more were seriously injured. Ford immediately withdrew its three-car team, followed by the other works teams. It was the beginning of the end for Group В and for the RS200’s WRC career, although Kalle Grundel came fifth in November’s RAC Rally.

Team-mate Blomqvist had less luck, adding the Acropolis and RAC Rallies to his list of RS200 retirements.

The premature axing of the RS200 project meant that a proposed evolution model never saw the light of day on WRC events, but it did appear – and was hugely successful – on British and European rallycross events in the late ’80s and early ’90s. Stig Blomqvist won the Swedish Hilldimb Championship in an RS200, 1987-89… and hill-climbed a 650bhp RS200 at Pikes Peak in 2001 and ’04.

Audi Sport quattro

We’ve said it before, and we’ll say it again – one day these cars are going to rival vintage Bugattis for desirability.

A ludicrous claim? Well, a couple of Sport quattros have changed hands in recent times for about £80,000 each, and you’d probably need to find £100,000 for a really good UK-spec example now. And, as the song has it, the only way is up – for several reasons.

Consider the facts. The Sport quattro has unimpeachable motor sport heritage, it’s rare -only 224 were built-and it’s supremely rapid. But it’s also a genuinely usable supercar. Its interior is as comfortable as a regular quattro’s and the only sacrifice you pay for having a 300bhp engine, Porsche 917 brakes and better weight distribution is zero legroom in the back for passengers. We could live with that.

Although the quattro had revolutionised rallying when it debuted on the WRC in 1981, its front-mounted engine compromised weight distribution and handling. It was soon outclassed by the purpose-built, mid-engined Peugeot 205T16 – and, in truth, it could never catch up while it remained front-engined. But Audi was determined to try.

Enter the Sport quattro, whose balance was improved by the simple expedient of chopping 320mm (12.6in) from the middle of the car, although body panels were also remade in a mixture of GRP and Kevlar. There was a new all-alloy twin-cam 2.1-litre engine, rated at 306bhp for the homologation cars but tunable to 400-450bhp for rallying. With the standard engine, quoted performance figures were 0-60mph in 4.9sec and a top speed of 155mph. The Sport quattro was only available in lefthand drive and, to avoid UK Type Approval problems, had to be brought in as a personal import after pre-registration in Germany. Only six cars are known to have been made to UK spec (RHD headlights and speedometer calibrated in miles), including our feature car which is owned by quattro specialist Roger Galvin (www.thequattroworkshop.co.uk).

‘It’s a tiring car to drive really fast on twisty roads,’ admits Roger, ‘because 300bhp in a car with a wheelbase shorter than a Metro’s makes it a bit twitchy when you put your foot down! It will handle motorways just like any other Audi, but that seems something of a waste… Having a turbo the size of a dinner plate also means there’s nothing below 3500-4000rpm, but after that you can’t change gear fast enough. Ideally, at lower revs you left-foot brake and use the right foot to keep the engine spinning.’

Although the cars were built to Audi’s usual high standards, the alloy engine block has thin steel liners that can wear through in 60,000 miles, and it’s rumoured that Audi deliberately cast a spare steel block for every alloy one! Otherwise they are reliable, being based on running gear that was by then well proven. Some people find the looks challenging – ironically, the Sport quattro’s nose is actually longer than a standard quattro’s, to accommodate a bigger intercooler – but its boxy profile (penned by Sheffield-born designer Martin Smith) is unmistakably ’80s. And that’s another reason we think the Sport quattro is a sure-fire future superclassic.

Right Engine was a new, all-alloy design with twin overhead camshafts and four valves per cylinder: in road tune it gave 306bhp. Below Sport quattro did without the digital dash fitted to regular quattros; an unnecessary complexity in a car built to go rallying. Thanks to our Quattro/Coupe Club

RALLYING THE QUATTRO

Audi wasn’t the first manufacturer to rally a 4WD car – two Subarus and a Range Rover appeared on the 1980 East African Safari – but it was the first to exploit the potential of 4WD.

The original quattro had its first outing on the 1981 Monte Carlo, where a pair of cars were driven by Hannu Mikkola and Michele Mouton. Sadly, both failed to finish.

It all came good on the next event, the Swedish Rally, where Mikkola devastated the opposition. It was not only the first WRC win for a quattro, but the first for any 4WD car.

The next couple of years were good for Audi: seven WRC victories in 1982 and five in 1983, although continual problems with reliability cost it the Manufacturers’ Championship both times. By now its rivals had jumped on the same 4WD bandwagon and the quattro’s card was well and truly marked from the middle of 1984, when a Peugeot 205T16 won the 1000 Lakes in Finland.

Audi homologated the new Sport quattro on 1 May 1984, and for a while both regular (A2) and Sport models ran in the same events – some drivers, such as Mikkola and Stig Blomqvist, preferring the old car on the grounds that the Sport’s extra power only increased its understeer. And of the seven WRC wins for Audi that year, six of them were with the old A2 model.

Still, Audi decided to go all-out with the Sport quattro for 1985. On 1 July the E2 version was homologated, with a huge shovel-like front spoiler and rear wing to add downforce, big air intakes everywhere and the radiators moved into the boot to improve weight distribution.

The E2 was better, but still not good enough. It clocked up just one victory, on the 1985 San Remo, but still struggled against the new, improved 205T14 E2. And Lancia’s Delta S4 was just around the corner.

Audi’s dilemma became irrelevant after the disastrous 1986 Portugal Rally, when it retired from world rallying. The E2 had one final burst of glory in 1987, at Pikes Peak hillclimb in the USA: Walter Rohrl in an E2 beat Ari Vatanen by just seven seconds – and Vatanen was in a T16. A small consolation, if rather too late.

’The Sport quattro’s balance was improved by the simple expedient of chopping 320mm from the centre of the car’

MG Metro 6R4

Indubitably the ugliest-looking of our five-car group, the 6R4 drew more attention during our photoshoot than any of the others. That’s partly because this example is beautifully presented. But it probably also has something to do with a natural gravitation towards the underdog – and cash-strapped Austin Rover, struggling to pursue an ambitious motor sport programme in the 1980s, was certainly that.

The 6R4 may look as though it was cobbled together in a shed but it’s a remarkably ingenious machine. Overseen by experienced rallyman and AR Motorsport boss John Davenport, it’s the only non-turbo Group В supercar, having an all-new normally aspirated 3.0-litre V6 that was a legacy of early experiments with a cut-down Rover V8.

Austin Rover’s engineers decided to stick with the V6 for two very good reasons: non-turbo engines stand a much better chance of going the distance on a tough rally, and a big-capacity non-turbo engine has a nice broad spread of torque, ideal for rallying.

The engine was the brainchild of AR motor sport engineer David Wood, but the rest of the car drew heavily on input from Williams F1 under the guidance of Patrick Head, with four-wheel-drive expertise from Tony Rolt’s FF Developments. Cars built to the entry-level Clubman spec had glassfibre panels around a central steel tub and regular Metro steel doors, but the pricier International-spec 6R4 gained Kevlar panels all round.

To avoid having to be Type Approved, the 6R4 was sold in ‘kit’ form as a competition car, rather than as a road car toy. The idea was that it would be one of the most cost-effective ways for privateers to go rallying. Works driver Tony Pond said in 1985: ‘The car is very easy to drive – and very fast at only eight-tenths. You would not need to be a top-class driver to win with it.’

Buyers of a Clubman-spec car, in return for stumping up about £40,000, received a 250bhp version of the V6 engine, whereas the International-spec cars had peakier 410bhp motors and cost another £10,000. But 250bhp was more than adequate in a car weighing around 1000kg and geared for acceleration rather than maximum speed, as journalist Gavin Green found out in another Car road test – or rather, off-road test – at a Welsh rally school, early in 1986.

‘The car accelerates down a dirt road, between the trees, like a Porsche 911 Turbo would on a B-road,’ he wrote. ‘But you will be bouncing around the cockpit rather more than you would on tarmac… Sometimes, those pine trees get close. Your tendency is to back off when the trees threaten to assault. By backing off, the car slows dramatically – the engine braking is quite enormous – and also tends to straighten. Then it’s simply a matter of steering the car back towards the tracks in the centre of the road, where the grip is much better.’

Gavin Green also tried the car on road, where he found it embarrassingly noisy and undergeared, with 7400rpm in fifth equating to only 110mph. ‘The car feels just what it is,’ he summed up; ‘a Metro with the power of a Ferrari quattrovalvole V8, the traction of a quattro and the strength of a Land Rover.’

The 6R4’s unsuitability as a road car perhaps explains why our feature car had only covered 1000 miles when current owner Jonathan Rennison bought it. That total is now up to 3500, and last year Jonathan had a go at hillclimbing in it. ‘It’s never let me down but mine has the cambelt “reliability kit” fitted, which includes extra belts, pulleys and covers – they had a reputation for throwing belts when new, ‘he says.

It wasn’t that long ago that you could buy a 6R4 for £15,000. Now the typical asking price for a Clubman is £50,000, while a full-house rally car is £75,000-80,000. People are still rallying the 6R4, it seems – just as Austin Rover’s motor sport team hoped they would, a quarter of a century ago.

‘The 6R4 is the only non-turbo Group В supercar, having a normally aspirated 3-litre V6 that was a legacy of experiments with a cut-down V8’

Left and below Jonathan Rennison’s immaculate 6R4 may have token interior trim but is clearly intended for rally stages rather than roads.

RALLYING THE 6FU

Austin Rover Motorsport had promised that the 6R4’s first International rally would be the 1985 RAC, and they made it with just days to spare. Two cars were entered for Tony Pond and Malcolm Wilson, who faced stiff opposition from Mikkola and Rohrl in quattro E2s, Salonen, Grundel and Mikael Sunderstrom in 205T16s, Waldegard and Kankkunen in Toyota Celica TCTs – and Alen and Toivonen in the newly homologated Lancia Delta S4s.

Wilson was delayed by a broken cambelt – the 6R4 engine was prone to catching stones, which would dislodge the belt – but Pond finished a hugely impressive third, behind the two Delta S4s.

It was a great start.

Hopes were therefore high for the 1986 Monte Carlo – scene of the Mini triumphs two decades earlier – but both 6R4s retired with mechanical trouble. And it was a similar story on the Swedish Rally: cambelt trouble yet again.

Next came the ill-fated Portuguese Rally, where the 6R4 of Marc Duez was the first car to discover the wrecked Santos RS200. The works teams all withdrew. After that it was a very mixed bag of results for the rest of 1986. There were many retirements due to accident or mechanical damage but some decent finishes too. notably on the 1000 Lakes of Finland, where Eklund, Harri Toivonen and Wilson came home 7th, 8th and 10th respectively – even though Wilson rolled his car. There was compensation for Wilson when he picked up 4th on the San Remo.

The 6RA’s swansong, fittingly enough, was on the 1986 RAC Rally, for which no fewer than seven examples were entered. An estimated 50,000 rally fans watched the first day’s stage at Trentham Gardens and the home crowd was eventually rewarded by 6R4s finishing 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th and 17th overall. Tony Pond was the highest-placed 6R4 driver, despite having had to complete a full stage in two-wheel drive after his front differential broke.

Having been designed for privateer ownership, the 6R4 fared less badly than many more specialised cars in the post-Group В era, and went on to have a distinguished career in British and European rallycross events.

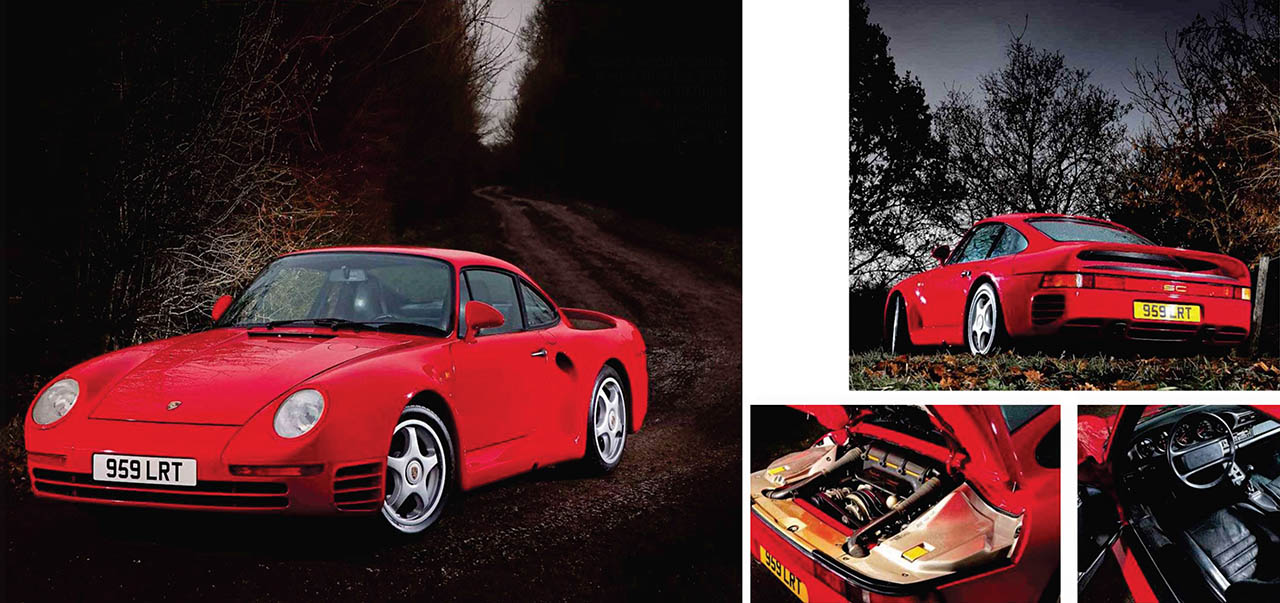

Porsche 959

A tyre-pressure monitoring system that uses the hollow-cast spokes of magnesium alloy wheels – that pretty much sums up the 959. This car was packed with technology like that, technology that would seem pretty impressive on a 21st century car. But the 959 dates from the mid-1980s, when computers as we know them were still in their infancy. Porsche being Porsche, it embraced the new technology and made it work.

The 959 first made its appearance as a concept at the 1983 Frankfurt Motor Show but the first customer cars didn’t trickle off the production line until well after Group B, the primary impulse for its existence, was long dead and buried. It had one big advantage over the cars built for homologation by its would-be rallying rivals, however: it was a supercar that also happened to be rather good for rallying and racing, rather than the other way around. So it was relatively easy to sell, even with a £155,000 price tag.

Our feature car is the standard or Comfort model – kindly loaned by owner Andy Wood – but there was also a rare lightweight Sport version, which was listed at £175,000, although speculators were paying far more than that in the stupid years of the late 1980s. As usual with Porsche, for more money you got less car, thanks to the deletion of air-con and the trick speed-related, self-adjusting ride height.

Clever aerodynamics meant that the 959 could reach 197mph without needing spoilers and wings tacked all over it, and four-wheel drive helped give it stunning acceleration: 0-60mph in 3.9sec. The 2850cc flat-six had twin sequential turbos to minimise turbo lag, water-cooled heads and dry-sump lubrication: road cars developed 450bhp DIN, but the Paris-Dakar rally cars had closer to 600bhp and the Le Mans 961 an impressive 640bhp.

Octane international editor Robert Coucher compared a Porsche 959 with a Ferrari F40 in issue 55 and reported: ‘This is a ferociously fast machine once the engine wakes up. It emits a lovely wail which is never intrusive… It is softer than the Ferrari but more manageable. The brakes are sensational… the ride is fluid, the steering nicely weighted but not as sharp as the F40’s.’ But Robert went on to say: ‘Since the 959 was first seen at Frankfurt, technology has caught up. Now, a standard 911 will do almost everything the 959 does. The F40 eschewed technology… it is a crazy weapon [and] that’s why we love it.’ It’s a very good point – where classics are concerned, character still weighs more heavily than cleverness.

Many thanks to the owners of the featured cars, and to Avalanche Adventure outdoor activity centre for the photo location. This Leicestershire-based site offers a wide range of off-road, air- and water-borne attractions: see www.avalancheadventure.co.uk and Drive-My 959 Porsche Club

Above and left in its private war with Ferrari. Porsche uprated late 959 Comforts like this one by chipping the engine to 525bhp. Engine was capped at 2.85-litres to suit Group B’s 1.4 multiplier for turbocharged engines, which gives it a theoretical 4.0-litre capacity.

RALLYING THE 959

The Porsche 959 was never actually homologated for Group B, and it never ran in a WRC event. But it did have a spectacularly successful, if spectacularly short, career as a rally car.

Porsche certainly targeted the 959 at Group B. The rear-wheel-drive 911 had proved itself an excellent rally car, ever since its trio of victories on the 1948-70 Monte Carlos. By January 1984 a 290bhp SC RS version had been homologated for Group B, with which Henri Toivonen won the European Rally Championship.

But Porsche had already started working on a 4 WD turbocharged development of the 911 in early 1983, and it was encouraged by an unexpected privateer success in January 1984. Three 4WD SC RS rally cars had been built by Prodrive and entered for the Paris-Dakar with Rothmans sponsorship, running detuned 220bhp engines to cope with low-octane fuel. Rene Metge brought one home 1st overall, Jackie Ickx finished 4th, and the third car – driven by engineer Roland Kussmaul – came in 27th.

Suitably inspired, Porsche entered three development versions of the 959 for the 1985 Paris-Dakar, still running normally aspirated 3.0-litre engines. Driven by Metge, Ickx and Jochen Mass (Kussmaul had been relegated to a Mercedes G-wagen support vehicle), all three cars retired due to various accidents.

But the 959 finally came good on the 1986 event. The cars were fully evolved, the driver line-up was the same as on the 1984 rally, and the results vindicated Porsche’s faith in the project: Metge 1st, Ickx 2nd and Kussmaul 6th. It was too late as far as Group В was concerned.

Porsche had still not homologated the car, and the first customer deliveries were not made until late April 1987. A racing version of the 959, coded 961, did well at the 1986 Le Mans 24 Hours and finished 7th overall (it was up to 11th in the 1987 race, until its driver missed a gear and crashed it); but the legacy of the 959 was not so much its competition history as the technological expertise Porsche gained through building it.

‘Clever aerodynamics meant that the 959 could reach 197mph without needing spoilers and wings tacked all over it’

The Group В cars that time forgot…

You’ve just read about the heroes – though it would hardly be fair to call these zeroes, says Keith Adams

Mazda RX7

The Wankel engine is tiny compared with its Otto equivalent, and meant that the fledgling Mazda WRC team could very effectively package a Group В RX7 – even though the authorities demanded a reduced capacity 1.5-litre twin-rotor turbo under the equivalency formula. A lack of budget at Mazda Europe meant that the car’s undoubted potential could not be achieved. But it paved the way for the post-Group В 323 AWD.

Opel Manta

The Manta 400 Group В was a very effective update of the Group 4 car, which itself was an evolution of the Ascona 400, a surprise winner of the 1982 WRC Championship with Walter Rohrl behind the wheel. The main change for Group В was the addition of carbon- Kevlar body panels. It wasn’t enough for the Opel team to remain competitive, and paved the way for the company to develop its Group S Kadett.

Toyota Celica

The Celica TCT or TA64 was a Group 4 evolution, being a turbocharged version of the RA63. With extensive rallying experience, Toyota produced an effective challenger that, once on-song, pushed out 370bhp from 2.1-litres. The events on which the reliable Celica TCT really shone were the Safari, where it won in 1985 and 1986 and the Ivory Coast, where it also took victory. Toyota’s best years would follow in Group A, though.

Escort 1700T

The arrival of the front-wheel-drive Escort Mk3 in 1980 left Ford with a problem. To stay competitive in rallying, it developed the rear-drive Cosworth BDT-engined RS1700T. But it took so long to develop, the RS1700T found itself rendered obsolete by the four-wheel-drive Audi quattro even before it hit the gravel in anger. It was scheduled for production in early 1983, but Stuart Turner cancelled the project in favour of the RS200.

Citroen BX4TC

The BX4TC was the answer to a question no-one had asked. Not least because corporate stablemate Peugeot had already enjoyed considerable Group В success with the 205T16 by the time of its debut in 1985. The in-line Peugeot XU engine was turbocharged to 380bhp, but the BX4TC was hampered by poor weight distribution and, following unpromising outings prior to the 1986 Championship, Peugeot pulled the plug.

All the Group В rally pictures on this and previous pages are from the excellent book Group В – the rise – and fall of rallying’s wildest cars. Written by experienced rally man John Davenport – who led the Metro 6R4 programme – and Slowly Sideways club founder Reinhard Klein, it has parallel English and German text and explains every nuance of the Group В saga, along with detailed histories of all the cars involved. It’s published by McKlein at €49.90. See www.rallywebshop.com.

{CONTENTPOLL [“id”: 57]}