Pieces Of Eight. Alfa Romeo vs Triumph ’30s thoroughbreds go head-to-head ‘If you make a copy, base it on the best,’ thought Donald Healey. Mick Walsh unites an historic Triumph with the Alfa Romeo that inspired it. Photography Tony Baker.

Can you imagine Jaguar borrowing a two-year-old Ferrari today, and producing a refined copy with Modena management merely flattered by the development? Improbable though it seems, just such a situation arose in the 1930s between Triumph and Alfa Romeo.

Touring-style Spider looks magnificent from every angle, but particularly in profile. Inset: Schick racing 2311229 with flathead power and original bodywork.

When Donald Healey got the go-ahead to produce a new high-performance sports car with a limited budget of £5000, his design team borrowed an 8C Monza to strip and measure. Furthermore, when Healey visited Milan to discuss the project, the Alfa management was honoured that such a famous British company had decided to follow its design. There was talk of a Triumph-Alfa badge and even of Triumph motorcycles being produced in Italy, although in the end nothing came of either proposal.

Dolomite’s current body combines original Corsica styling with bolt-on embellishments. Inset: Healey finishes 1936 Monte eighth after spinning in final test.

The result of Healey’s work was one of the great might-have-beens of motoring history, a British sports car to finally match contemporary European rivals. The 2-litre supercharged straight-eight with its pre-selector gearbox was enthusiastically received by press and wealthy aficionados on its debut at the 1934 London Motor Show, but the bold Alfa-inspired exotic’s time was sadly short-lived. After just one completed car, a show chassis and two attempts at the Rallye Monte-Carlo, the project was axed, the name alone continuing on the firm’s more mainstream six-cylinder offerings.

The sole Dolomite finished by Healey’s team emerged from restoration last year, and the idea of finally matching it against the legendary Italian machine that had inspired its designers eight decades ago was warmly received by two passionate owners – Alfa Romeo devotee Paul Gregory and Healey fanatic Jonathan Turner.

First to arrive at our chosen rendez-vous is Gregory, the signature roar of his glorious Alfa 8C audible long before the magnificent grey Touring Spider comes into sight. A firm believer in driving his dream pre-war car, Gregory has motored over the Wessex Downs from Marlborough – battling the rush hour on a particularly wet morning. “I never put the hood up,” he tells me, adding that, with the high-ratio axle, the car will cruise at 80mph on a light throttle. “That surprises a few modern drivers, although the braking is the main consideration.”

Alfa 8C ownership is an ambition fulfilled for Gregory, who has been “playing around with” pre-war cars since building a Riley special at university. His indoctrination into the Milanese marque, meanwhile, started with a Sprint GT in 1972. Later projects have included a self-built Riley Autovia V8 special and a spectacular aeroengined Hispano road car. “The 8C has lived up to my expectations, and working with specialist Jim Stokes’ team during the rebuild was hugely rewarding,” he enthuses, “but finally getting to drive the car is as good as it gets. I’m planning a few hillclimb events this year and a trip to France, but wouldn’t dream of trailering it.”

Turner is equally passionate about his Triumph Dolomite, and the even rarer original engine hasn’t deterred its use. Since a full rebuild by Blakeney-Edwards Motorsport, DMH 1 has successfully completed the 1000 Mile Trial, chased Bentleys around the Portimão circuit in the Benjafield 24, and will be out on the Flying Scotsman this month. “It’s beautiful to drive and goes like the clappers,” says its proud owner, “but best of all for me is that it’s British.”

To see the 8C Touring Spider and Straight Eight parked nose-to-nose is a singular moment at our test, and maybe a first coming together. Immediately, the late-series, high-radiator 8C body looks lofty and more vintage, its pumpedup poise with twin spares on the back clearly derived from the earlier 6C-1750. From every angle the car’s proportions evoke its thoroughbred breeding and remarkable racing pedigree, while the Coventry challenger has a leaner appearance aided by the louvred chassis valance, wider radiator, lower Marchal headlights and taut bonnet. In contrast to Triumph stylist Walter Belgrove’s original homage to the Dolomite’s Latin inspiration, the later Corsica coachwork is certainly better resolved, more elegant and distinctly English in its style.

With such close specifications, you’d imagine that the two cars would have very similar driving characteristics but they prove quite different, confirming that the Triumph engineers had really pushed the Milanese design forward. With its higher steering wheel and deep padded leather, the Alfa’s cockpit seems the more old-fashioned of the pair. The intrusive centre transmission and oil tank nestling under the seats make it feel quite cramped, while the driver sits higher and more exposed to the elements. The trickiest feature of any 8C is normally the gearchange, but a modern clutch and dog ’box developed by Jim Stokes Workshops transform this car. The action via the long, slender, hooked lever is now slick, which perfectly matches the magnificently torquey power delivery of Vittorio Jano’s legendary straight-eight.

The worm-and-wheel steering is high-geared and beautifully weighted. Through the turns the action loads up nicely, which superbly complements the Alfa’s involving and predictable vintage-style handling. The rod-operated drum brakes have good feel but demand respect with such formidable power on tap – Stokes-built engines are now producing well over 200bhp. The performance is staggering, and is enhanced by the wonderful deep bellow of the engine. The aural mix of exhaust, induction, supercharger and transmission equates to one of the most distinctive pre-war sports car sounds. The throttle – moved from the centre to the right here – is sublimely responsive, and even a gentle prod will sweep this beauty out of corners at an astonishingly rapid pace.

The stiff front end and more flexible rear combine with the flex of the chassis to give the 8C brilliant handling, but it’s the engine that dominates the Alfa’s character. Be it storming away from an apex in second, or blasting down a straight in top, the punch is spectacular. If it’s impressive today, I can’t imagine what a heady sensation it must have been in the early ’30s.

If you’re going to copy a design, then it makes sense to start with the best. Healey – no doubt influenced by Alfa exponents ‘Tim’ Birkin and Earl Howe – fully appreciated the 8C’s dominance, but the Dolomite is quite different from the moment you slip under the lower raked fourspoke wheel. Contrasts include the traditional wood dash against the Alfa’s crackle paint finish, more supportive seats compared to a deep padded bench, and a much roomier footwell thanks to the flush fitting of the pre-selector gearbox with the floorboards. With his extensive rally experience, Healey understood the importance of driver comfort, and inside you feel more a part of the British machine.

The engine has a sharper bark but the action of the gearchange is the biggest difference. Select first through the short lever on the quadrant to the right of the steering column, and the heavy weight of the pedal floor ‘switch’ initially contrasts with the light conventional clutch of the Alfa. But once into the higher ratios, the lighter and shorter action of the hand lever is a revelation. Little wonder the likes of Prince Bira and Whitney Straight were converts to the Wilson design for racing.

Once in tune with the pre-selector, the Dolomite’s other impressive features are better appreciated. The steering is as good as the Alfa’s but the ride is much smoother with more refined damping. The handling, in part due to the better weight distribution, feels more composed than the 8C’s slightly skittish character. This is confirmed by previous owner Julian Majzub, who maintains it would out-corner the Italian car. Even in the wet it feels beautifully balanced.

Due to the slight power-sapping drag of the pre-selector, the Dolomite doesn’t have quite the spectacular grunt of the more developed 8C, but make no mistake, the acceleration is very strong. The combination of a shorter crankshaft, revised firing order, and vibration damper equals a smoother delivery, and bestows the Triumph with more of a rasp to the exhaust note.

“On the dyno it gave 190bhp, so it’s no match for a well-sorted 8C,” says restorer Patrick Blakeney- Edwards, whose company has also rebuilt several historic Alfa 8Cs, including the 1934 Le Mans winner. “But on the road it just feels fantastically competent – it’s as good as any prewar car I’ve driven. The brakes are stupendous, the steering light and the ride excellent. It’s perfect for unstressed high-speed motoring.”

Intimate with the design and road manners of both cars, the respected specialist is able to offer a unique perspective here. “The Alfa was already outdated by the time that the Dolomite was unveiled,” he says. “The chassis and dimensions are similar, but the Triumph is lighter and shorter, while Healey went to great lengths to reduce the mass of the engine, using magnesium alloy for the crankcase and cam covers.”

With its torque tube, the Alfa’s rear axle is better located than the fully live set-up on the Triumph. Added to that, the Coventry car’s springs are lighter with fewer leaves, which with the Luvax hydraulic dampers at the back – the 8C has friction units all round – contributes to the better ride. “The Alfa is more wayward,” says Blakeney-Edwards, “but the turn-in is superb. For me it feels as if it was built for competition, particularly around a circuit such as Le Mans, whereas the British car is a more comfortable and consummate design that’s better suited to rallies in the South of France.”

There’s no doubting the desirability of either car. While the Alfa’s pedigree and spectacular character make it the obvious choice, the Dolomite’s subtler charms, rarity and fascinating story are just as tempting. Best of all, the lucky owners of both cars are fanatical about driving them. Jano and Healey would approve.

Triumph Dolomite DMH I

It’s believed that Triumph built three complete chassis and six 140bhp 1991cc engines before management pulled the plug on the project in 1936. Of those three, just two survive. The first, DMH 1, was badly damaged on a foggy night in December 1935 when, at the start of the Rallye Monte-Carlo, Healey had a close call with a train on a Danish level crossing. The second chassis, DMH 2, was prepared to a dazzling standard for the 1934 Olympia Show but was never bodied by the factory.

Triumph management agreed to rebuild the Monte-Carlo car for a second crack at the event, and for that the unfinished third frame was used. Fitted with an unsupercharged engine bored out to 2485cc and, mysteriously, smaller brakes replacing the original 16in Alfin drums, Healey started from Tallinn, Estonia. After a smooth run on the mildest Monte for years, he arrived at the Côte d’Azur in fourth, but a rare mistake on the final driving test on the Monaco seafront dropped him to eighth. Triumph suffered a terrible financial year in ’36, and as a result the costly eight-cylinder project was cancelled. The Monte-Carlo car and all the spares were acquired by a 19-year-old Tony Rolt, the £850 asking price paid by his mother. Stripped of wings and with the blower reinstated, the Dolomite was entered for the 1937 200-Mile race at Donington where Rolt finished a creditable eighth among a grid of single-seaters including ERAs and Maseratis.

When Rolt acquired ‘Remus’ – ERA R5B – the Triumph and associated spares did the rounds of the London dealers. High Speed Motors instructed Corsica coachworks to rebody the Monte-Carlo car, while the second chassis was also completed with an ugly redesigned grille. The Triumph’s original engine was removed later in life to power Lord Ridley’s speedboat, being replaced first with an Austin ‘six’ and later an SS100 unit. Thankfully, however, the car and engine were reunited in the ’60s.

Painted red, the Dolomite was acquired by the Majzub family and, after a mechanical rebuild by Duncan Ricketts, was much enjoyed – including a trip to the Mille Miglia where it had another close shave at a railway crossing.

The Dolomite was eventually sold to France in 2000 but is now back in the UK with Jonathan Turner, who also has a Squire in his impressive collection. Upon acquiring the car, Turner immediately instructed specialist Blakeney-Edwards Motorsport to fully restore it. After a complete mechanical rebuild, the Corsica body was subtly altered to evoke the Dolomite’s original Walter Belgrove styling – Blakeney- Edwards’ team cleverly devising several bolt-on features including scuttle cowls, chrome side flash, and Alfa-style tailfin, thus preserving the surviving style.

Alfa Romeo 8C Touring Spider

This stunning grey Spider, chassis 2311229, has a fascinating history involving a succession of intriguing owners. Born as a long-wheelbase car with handsome cabriolet body by Castagna, the first records show that the 8C was imported to the UK in 1935 for Cavaliere Aubrey Haskard Casardi, an Italian diplomat who used it around London. It’s not hard to imagine him making the most of the Alfa’s diplomatic numberplates to get himself out of scrapes with the police.

When the Casardis emigrated to America, they took the car with them to their new home in Missouri. After WW2 they sold it to the infamous Californian millionaire playboy, Tommy Lee, in whose stable the 8C joined a ‘Teardrop’ Talbot T150 and a Grand Prix Mercedes-Benz W154. The Alfa was much admired and featured in an early issue of Road & Track magazine, the author Harry Steele enthusing about a cross-country winter blast from Kansas City to California. ‘The trip was the sheerest form of pleasure,’ recalled Steele. Although much of Route 66 was icy and snow-covered, he wrote that ‘those rolling hills and sweeping curves of the Albuquerque Apennines were the perfect diet for an 8C Alfa.’ Lee raced 2311229 in local sprints and on the dry lake at El Mirage until his heavy right foot resulted in engine problems.

In 1950 the broken Spider was given to Gill Schick, a dapper LA car salesman who fitted a Mercury V8 and, complete with token whitewalls, entered the Palm Springs Road Races. Schick instructed Indycar race-engineer Emil Diedt to properly sort the Italian-American hybrid – scrapping the car’s original Castagna coachwork, shortening the chassis and fitting a sporty twoseater roadster-style body with cycle wings.

Finished off with Indy-style Halibrand wheels and a quick-change rear end, it was soon sold to Keenan Wynn, a movie actor with a passion for fast cars and ’bikes. Wynn encouraged business partner Tom Bamford to race the Alfa-Mercury, the car proving to be very competitive against imported Ferraris, Allards and Jaguar C-types. A Cadillac transplant followed in 1952, which kept the Alfa special at the sharp end of the pack in California events until it was Smitten with the Alfa-Cadillac, he struck miles home. When the new owner stopped en route for lunch, he was surprised to see a police patrol car pull up alongside, the officer reporting that he’d been chasing the roadster for over an hour! Nelson raced the car in local events until family commitments took priority, at which point the Alfa was pushed to the back of a barn, remaining there for the next half-century.

Fast forward to the late ’90s, and local racer Chuck McCain was called out to fix a burst water tank on a Tucson farm. While he was there the owner showed him an old red sports car buried under household junk. Over the following years McCain repeatedly tried to buy the Alfa and, after regular rebuttals, in 2000 his offer was finally accepted – but only if he agreed to retain it in the same guise as when raced by Bamford. No sooner had McCain started researching the car, than its valuable origins sprang to light. Nonetheless, he upheld his pledge to Nelson and, after a five-year restoration, the Alfa-Cadillac turned out for the Monterey Historics, causing quite a stir. Shrewdly McCain had removed all the genuine 8C components from 2311229, his plan being to restore it separately while the hot rod was reborn with a facsimile chassis.

Tragically, in early 2010 McCain was murdered, leading to Paul Gregory acquiring the project. He instructed Jim Stokes Workshops to complete the restoration, but rather than recreating the original Castagna body, Gregory opted instead to retain the short-chassis configuration and fit 2311229 with a replica Touring Spider body.

‘IT’LL CRUISE AT 80MPH ON A LIGHTTHROTTLE, WHICH SURPRISES MODERN DRIVERS’

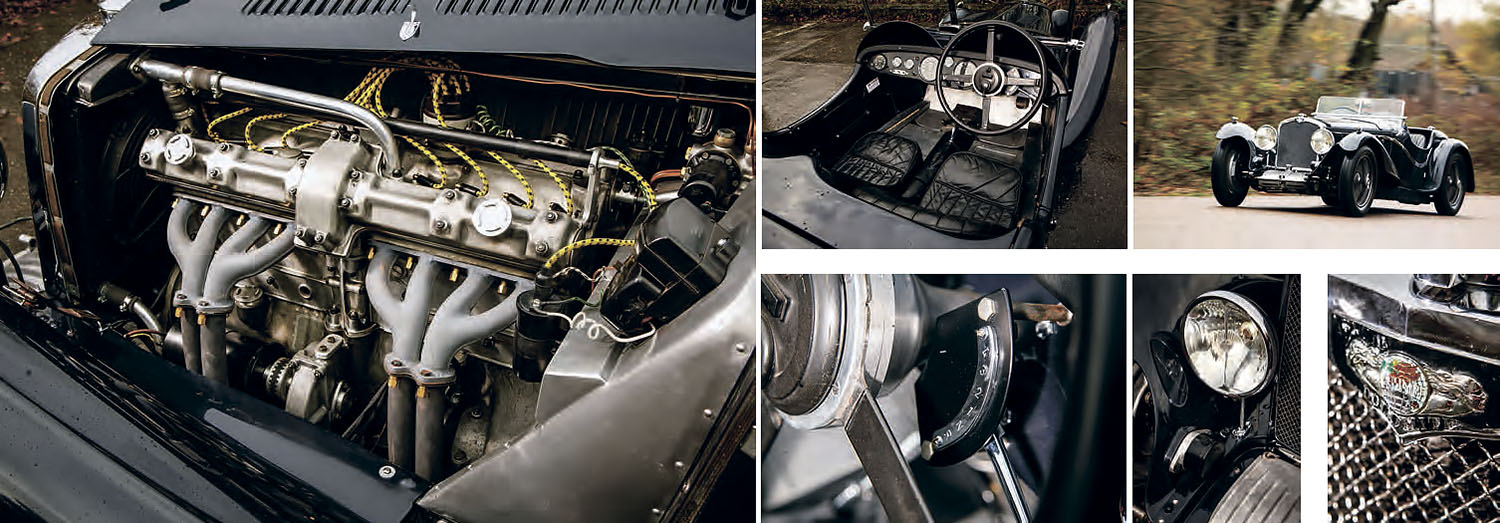

Clockwise, from above: engineering art, Alfa 8C 2.6-litre engine is two four-cylinder blocks with centre gear tower cam drive, blower and finned manifold; original chassis plate; crackle dashboard finish; RAC Italia badge; awesome performance; cramped cockpit with high-set steering wheel.

‘THE PERFORMANCE IS STAGGERING, AND ENHANCED BYTHE DEEP BELLOW OF THE ENGINE’

Clockwise, from above: Triumph engine looks like an Alfa’s but no parts interchangeable between the two; dramatic badge; distinctive radiator is wider than Italian car’s; lovely Marchal headlamps; fast-shifting pre-selector quadrant; roomy cockpit thanks to flush-fitting ENV-built Wilson ’box.