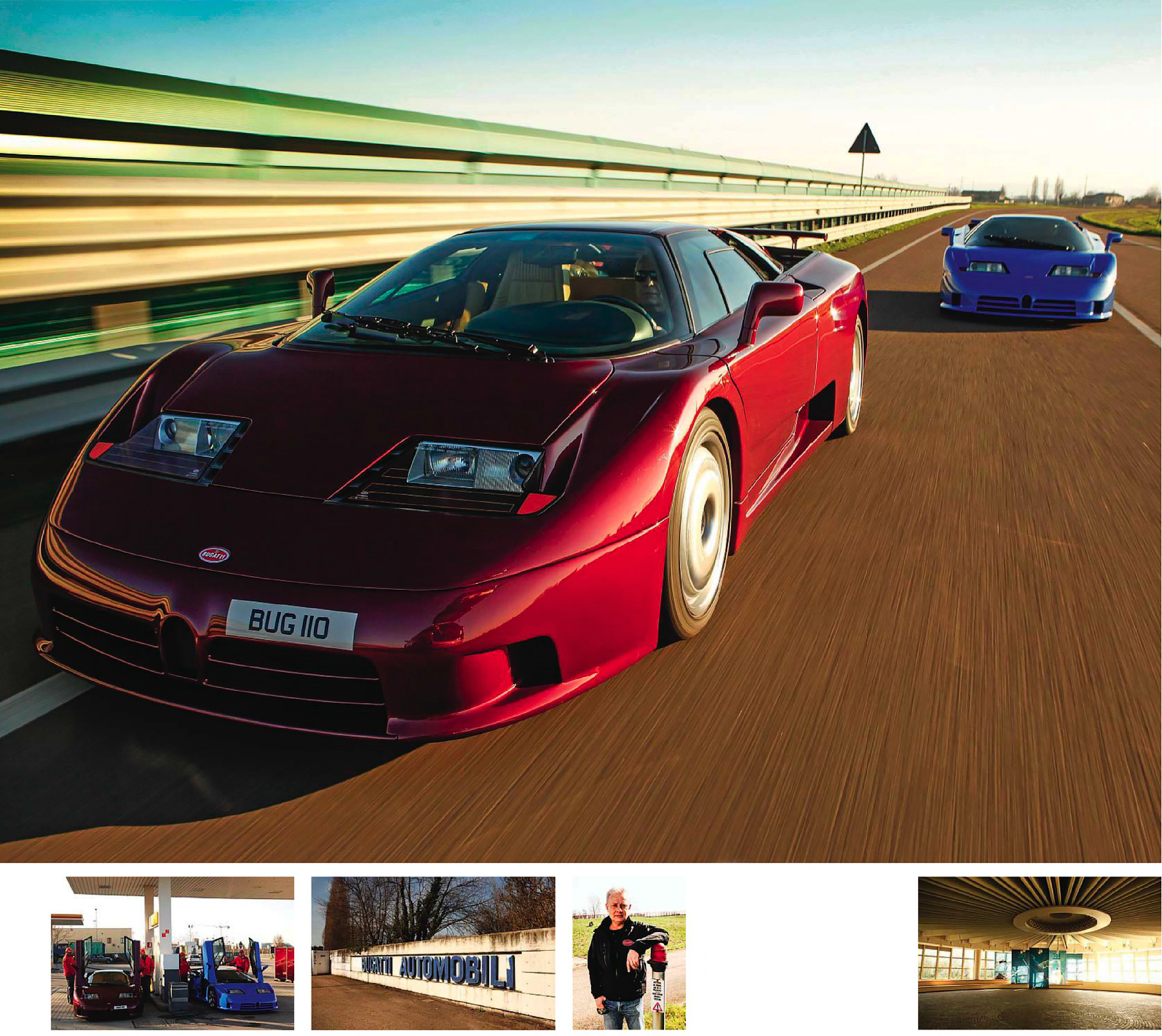

Return of the King. Mick Walsh makes a pilgrimage back to the factory where the Bugatti EB110 was built to investigate the 4WD sensation and meet the key players involved with its innovative design. Photography Tony Baker. There’s nothing like driving great cars on the roads where they were developed. Above: former test driver Trombi in GT leads racer Hancock in the SS into Campogalliano. From far left: four attendants fuel EB110 pair near Modena; evocative entrance; test driver Biocchi with track warning light. Right: empty showroom with Type 59-inspired roof.

Italians tend to be forward-looking, but we Brits indulge in nostalgia. Not since Bugatti EB110s were tested around the Emilia-Romagna region in the mid-1990s has a pair of these 200mph-plus four-wheel-drive supercars been seen heading back to their Campogalliano birthplace. Eagle-eyed locals might have noted the unfamiliar British registration plates of the maroon GT and rarer blue Super-Sports as they flash across the flat plains north-west of Modena. The duo are on a mission to be the first Bugattis to return to founder Romano Artioli’s dream factory since bankruptcy forced its closure in 1995, after just four years production and 150 cars.

The blue SS – one of only 31 produced – was built to special order prior to the shutdown because Artioli wanted his own EB110 as a celebration of the project. The specification of the 60-valve, quad-turbo, 3.5-litre longitudinally mounted V12 included power uprated from 553bhp to 603bhp. With just 14,000km on the clock, it was acquired by London dealer Gregor Fisken at Artcurial’s 2013 Retromobile auction in Paris for €448,900. Its unintimidating character was proven recently when Fisken’s wife celebrated passing her driving test with a run around London in the SS. Gregor couldn’t make our pilgrimage, but invited Le Mans and GT hot shoe Sam Hancock to deputise.

There’s nothing like driving great cars on the roads where they were developed, and we relish every mile as the sun sets across the fields.

“What a piece of kit,” enthuses Hancock after his first go in the ‘softer’ GT. “The further we drive, the more enthusiastic I am about this great car. The F40 was my all-time favourite supercar but this makes it look tame. The scissor doors are just as a kid would draw, and the remote-control button gives it ultimate casino appeal. Although I thought four-wheel drive would just add weight and complexity, I’m a convert. I’m surprised by how easy it is to drive around town, but the performance really delivers when you squirt it.” We stop to refuel before arriving at our destination and, with doors vertical like the wings of carrier-based fighter jets, the EB110s quickly attract four bored pump attendants who willingly fill the separate tanks. A lady in a Fiat arrives but gets no attention – even after waving cash – and eventually heads off to another garage. Both Hancock and I agree that the V12 sounds heavily silenced and deserves a louder rasp to make firing up more of an event.

“We fitted a sport exhaust for a German customer, but it was deafening after half an hour,” recalls former Bugatti test driver Federico Trombi, who greets us with a second SS. “The four turbos reduce the engine noise and I always stepped out relaxed after countless trips to Monaco from the factory, although the turbos sounded fantastic through the tunnels.”

The maroon GT is owned by broker Simon Kidston, who thankfully speaks fluent Italian and, after many calls, works his charm with ‘Ezio’, the caretaker of the empty plant. Late in the afternoon, after returning from another job, he agrees to open the gates and guide us around. None of the former Bugatti team has been back since 1995, so this is an emotional moment. “I feel like that Japanese soldier who hid away in the jungle and didn’t realise the war was over,” jokes Ezio, who now lives in Artioli’s former premises. It is a very JG Ballard-type scenario as the three

EB110s follow his battered Fiat Panda through the main gates at twilight. The purr of the idling V12s is almost drowned by the constant thrum of the A22 autostrada as we slowly weave along the overgrown service road and onto the test track that ran around the main building. Our headlights pick out the eyes of several large startled hares in the field at the back of the factory.

“A warning siren would sound, and red lights would start flashing around the buildings to warn other workers that cars were testing,” says Trombi. Glancing up, I spot the huge Bugatti badge on the familiar blue unit. It was painted over when VW acquired the famous name, but the red-and-white oval has slowly reappeared as paint flaked off over 16 hot summers.

The ex-Bugatti staff go quiet as the loyal guardian unlocks the main doors to the defunct assembly building. As the sky turns orange and turquoise through the glass roof, we marvel at the ghostly space where there was once a busy, optimistic scene. Now the pits are filled with rubble, oil and water, plus the grey monitors are long dead. The cars’ headlamps illuminate the line of hanging modules that still carry inspection lamps and power points, while through the side windows we can see huge ‘EB’ monograms decorating the walls of the engine rooms.

“This was a very high-tech factory when it was built, using a lot of green philosophy,” explains Ezio. “The engine test rigs would also run the air-conditioning in the summer and the heating in the winter. All of the oil used was biodegradable. Romano was passionate about gardening, and there were always flowers blooming.”

Trombi vividly remembers his last day here nearly 20 years ago: “There were 12 of us from the racing team working on the Le Mans car on a Saturday morning, and the main gates were locked. We ended up climbing over the walls to get out, and I’ve never been backuntil now.”

The atmosphere intensifies as night falls and the EB110s manoeuvre around in the darkness. I half expect ravers to break in and a ’90s electronic soundtrack to shatter the eerie calm, but amazingly – in this poor region – the factory has remained free from vandalism and graffiti. It’s a true Mary Celeste of motor manufacturing.

Ezio patiently agrees to take us on a torchlight tour of the headquarters. Following the white marble path, we arrive at the reception area where a Type 35 once stood. Old Car and Yachting magazines are gathering dust, while the final entries in the visitors’ book date from July 1995. A Japanese flag still hangs as a memento from the EB110’s Tokyo launch and the walls have cracks from earthquake damage. The round showroom has a spectacular roof inspired by a Type 59 wheel, and over in the corner is a basketful of unwashed espresso cups. “There used to be a bust of Bugatti but it was stolen,” says Ezio. “The showroom was out of bounds for 80% of the staff, and that’s the platform where Romano made some impressive speeches.”

Upstairs we visit the design centre where the last project was a jeep for the Italian army: “AH the walls were movable and on Mondays staff could arrive for work to find their office smaller or larger.” The only remaining paper in Artioli’s suite on the top floor is a business card from a banker in Modena. “Over the years,” Ezio adds, “I’ve been pestered by visitors who got my number, including an Argentinian. It turned out to be Horacio Pagani, who was looking for a place to build the Zonda.” There have been several plans for this monumental facility – including for a silk firm – but it’s now owned by a Rome lawyer who secured it for a bargain. Its future is still unresolved, though. At the bankruptcy auction, the cars and spares were bought by Gildo Pastor of the Monaco Racing Team, who quickly sold what he didn’t want and 16 20ft containers went by train to Dauer in Germany, which built a further handful of cars.

Campogalliano may look like a sleepy Italian town, but it hasn’t totally severed its links with Bugatti. Before we head back to Modena, we divert to an anonymous-looking warehouse not far from Largo E Bugatti. Inside the expansive workshop of B Engineering, I’m stunned to find six EB110s, several new carbonfibre tubs and enough spares to build five cars. Under wraps are a mint Lotus Elise, a rusty DS, Countach chassis one, and in the corner a gold EB110-based rear-drive-only Edonis. “We launched it at Geneva in 2000, and power is from a Bugatti V12 but with two large turbos rather than four,” says B Engineering partner Jean-Marc Borel, who was one of Artioli’s right-hand men at Bugatti SpA.

Knowing of Borel’s close links with the old company, I ask what his highlights were of the four years: “When the German magazine Auto Motor und Sport published a supercar group test in 1993 – with Michael Schumacher assessing a Ferrari F40, a Jaguar XJ220, a Porsche Turbo, a Lamborghini Diablo and our Bugatti EB110 – that was special. They used Goodyear’s Mireval proving ground in the south of France, and Schumacher was so impressed by the Bugatti that he decided to buy one. It was a great day when he visited the factory to collect his yellow SS with a GT interior. Only two were built to that specification.”

From top: plush cabin of GT, with wood facia; wide sill; best view through factory doors; motorised wing raised and perfect registration; Ettore’s famous monogram; packed V12 engine bay gets very hot, with quadruple turbos and catalytic converters; stunning traction and grip.

Where better to bring your EB110 for a service than to the team that built the cars and, during our visit, I’m distracted by the dramatic V12s on display. With their cylinder heads off, it’s fascinating to see the EB110s’ distinctive five-valve configuration and the IHI boosters.

“As with Maserati,” reveals Trombi, “we had problems with the first turbos getting very hot, which crystallised the oil. So, after the first 40 cars, we switched to a ball-bearing design that also spooled up faster and gave more low-down torque. All the Super-Sports had the later type.”

We have a secret guest at dinner that night, a name I’m told not to mention among the other ex-Bugatti employees because there’s still some ill-feeling even now. As we settle down in a cheery, family-owned restaurant on Via Emilia, I’m stunned to see Paolo Stanzani arrive. A close associate of Ferruccio Lamborghini, this sprightly 77-year-old engineer was a key figure on both the Miura and Countach as well as the EB110, but today prefers his cherished Lancia D20. After the tractor business was sold in 1972, Lamborghini was also forced to part with the car company but remained friends with Stanzani. “Losing the car business for Ferruccio was like losing his will to live,” he says, “and in 1985 he began talking to me about plans to start again. After the ’86 Turin Show, a meeting was arranged with Artioli, who was very excited about the project. He was too smooth for Ferruccio, who wasn’t interested in bringing automotive corpses back, but the money talk tempted him.”

In the end, Stanzani agreed to run the Development Department for a 30% share – although Artioli’s impatient and over-ambitious plans always made him uncomfortable. As Stanzani puts it: “We quickly got to the first prototype stage, but Artioli wasn’t happy with Gandini’s proposals. He kept saying we were trying to make another Lamborghini, which is why he brought in his cousin [Giampaolo] Benedini. Forme, the styling lacks personality. They tried too hard to make a Bugatti pastiche and should have started from scratch. Also, Artioli wasn’t an industrialist, and often tried to bluff his way – particularly over the company’s worth. He missed a great opportunity with tool-machine maker Mandelli, and wasted money on useless things such as the extravagant factory. Our suppliers also became nervous when he started rubbishing Ferrari. Like Ettore, he even had ideas about restricting buyers. I’m sure that Artioli just wanted blue- blood royals driving his cars.”

From top: one of the last of the 31 SuperSports (SS – Drive-My remark) built was for boss Artioli; fixed rear wing; cheese-grater inspired engine vents; all-black SS interior with carbonfibre seats and Nardi wheel – quilted leather trim features on sill and tunnel; distinctive Type 35-style alloy wheels.

Their differences caused a split and Stanzani was replaced by Nicola Materazzi, whose CV included the Stratos and F40: “I was sorry that it ended badly, but the car featured lots of firsts and the V12 was exceptional. PaulFrere was a friend, and he rated the EB110 as the best supercar.” Dinner ends on a merrier note with Stanzani enthusing about the best years at Lamborghini, and testing adventures with the late Bob Wallace. “The atmosphere was totally opposite to Bugatti,” he says. “We had one canteen that was shared by all – directors, staff and clients.” The final morning is all about driving because we plan to meet Loris Biocchi back at the factory and follow him on the old evaluation route west of Bologna in the Garfagnana region. Biocchi’s supercar background is impressive, starting with Lamborghini (the last Countach and prototype Diablo) via Bugatti, Pagani and Koenigsegg, plus he’s now the main test driver for the Veyron.

“Working here was the best time of my life,” recalls Biocchi. “The goals were ambitious but we had a fantastic team with great people from Maserati, Ferrari and Lamborghini. The spirit was inspiring and we developed many new ideas including floating brake discs, and even our own ABS. The EB110 was amazingly stable at high speed. Around Nardo at 334kph (209mph), I remember looking down to check the temperatures of the valves, and the car just kept going straight. You couldn’t do that in other supercars. Romano was like a second father to me. He was a little bit crazy yet in a good way. My colleagues at Lamborghini thought I was mad joining Bugatti, but I knew I’d made the right decision as soon as we started the first engine in the prototype. Every car I’ve driven evokes a different emotion for me, but the EB110 is top because it represents such a special period in my life.”

Above: EB110s return to their birthplace on the old production line. From far left: B Engineering’s Borel and Gianni Sighinolfi with stunning set of six EB110s; unmistakable Bugatti badge that VW ordered to be painted over; caretaker Ezio. Right: in formation around factory test track.

As Biocchi and his former colleagues explore their old workplace, I try the SS around the test track where many journalists first sampled the new Bugatti for scoop stories in April 1992. The plush tan leather and wood facia of the GT are an anticlimax after the dramatic scissor doors – more Ghia than exotic road rocket – but the stripped-back style of the SS has more atmosphere. The black-faced dash hides the dull switchgear while the carbonfibre seats by Poltrona, plus quilted hide over the sills and tunnel, give it more purpose. The Nardi steering wheel and the aviation-style overhead switch panel for the lights, ABS and fuel tanks enhance the cabin’s aura, as does the large rev counter set straight ahead reading to 10,000rpm. Many luxury items were deleted for the SS, including electric windows, while the motorised rear spoiler became a fixed wing that makes the rear-view mirror redundant. But even the lightweight model gets a Nakamichi cassette player.

Insert the key with its huge leather ‘EB’ fob, and the V12 starts instantly with a muted rasp but accompanied by plenty of mechanical whir from behind. The six-speed gearbox feels notchy and reluctant at low speeds – and takes ages to warm – but the action through the short, stubby lever gets slicker and more positive with downshift blips. The engine feels tractable, smooth and sophisticated rather than exciting until the small turbos spin up to dramatic effect at 4000rpm. The ride is well damped although it’s as firm as you’d expect for a 220mph machine. Over the worst bumps, the suspension is noisy but everything starts to iron out with speed.

After a few laps, I feel confident enough to nail the throttle on the short straights, and the performance takes on another dimension. The explosive delivery is awesome as the combined thrust and traction launch the EB110 NASA- style to the next turn. Finally the soundtrack matches the moment as the IHI quartet chuffs quickly in turn. There’s only room to use the lower gears, but the mighty punch pins you to the seatback and prompts a huge, mischievous grin. Later, out on faster roads, Hancock and I are impressed by the smooth, reassuring flow of power, which is a total contrast to the edgy drama of the F40. The engine note transforms into a distinctive snarl at the top end, but more interesting is the dramatic flutter of the waste- gates when you come off the throttle into bends.

You quickly crave quieter roads to really explore the EB110 and, with Biocchi leading on familiar routes toward Pavullo nel Frignano, the pace quickens as the traffic clears. A new Ferrari heading back to Modena flashes its lights, and Hancock has to work harder to chase the GT. After a gripping cat-and-mouse run between these two great drivers to the top of the local hills, we stop for a much-needed espresso. “There’s an extraordinary amount of grip from the 4WD and, try as I might, I couldn’t break traction,” says Hancock. “Only when braking are you really aware of the extra weight, and the floating discs don’t feel as firm as I’d like. The weighting and ratio of the assisted steering is perfect, but it really loads up through hairpins and you’re forced to shuffle the rim. Coming out of tight corners is a challenge because you’re too far off the power band, but keep the turbos spooled and the performance is phenomenal. From 5000rpm all the way to 9000rpm, it feels as if you’re strapped to a missile – with no sign of falling off.”

Hancock had a poster of an EB110 on his wall as boy, but he’d not seen one until this trip: “For such a big old car, it has really impressed me. Together with the McLaren F1, it marks the end of an era before everything got too gadgety.”

Today the Italian Bugatti looks great value, particularly when you consider that you could buy most of the SS production for the price of an F1. Why the EB110 doesn’t induce the same buzz as its rivals is hard to pinpoint, but maybe its unorthodox styling and clever engineering diluted the fiery soul that fuels ultimate supercar desire. One thing is clear, though: there was no lack of passion during its development.

Thanks to Simon Kidston and Emanuele Collo (kidston.com), B Engineering and Sam Hancock and Bugatti EB110 Club

Did you know?

The first planning meeting was at La Florita, Ferruccio Lamborghini’s vineyard in Panicale, in 1986, with Stanzani and Bertone as guests. Artioli was introduced at the second session: he proposed Isotta-Fraschini or Bugatti as the name, while Lamborghini was keen on ‘Ferruccio!

Giorgetto Giugiaro presented renderings at Turin in 1990. The ItalDesign sketch featured a dome-shaped glass roof, a la Lotus Etna, and softer lines but no Bugatti-style grille. The wheels were inspired by the Royale.

The original had an aluminium tub, but it lost 20% stiffness after 30,000km of testing prompting Bugatti to contact Aerospatiale, which helped to develop a carbonfibre version: a production car first.

On 29 May 1993, during type-approval testing at Nardo in Puglia, the SS broke the World Speed Record for GTs, at 351kph (219mph). Passenger plus luggage were simulated with sandbags, and the car ran with a full fuel load.

The EB110 failed to break 8 mins around the Nordschleife by one second in 1992, but test driver Loris Biocchi returned with a lightweight SS in 1993 and clocked 7 mins 44 secs.

A four-door limo (EB112) featured a 460bhp 6-litre V12 up front and 4WD. The joint venture with ItalDesign, led by Mauro Forghieri, was shelved after three prototypes were built, but the concept was revised forthe 18-cylinder EB118, the first Bugatti shown by new owner VW at Paris in 1998.

Other features explored by Bugatti’s design team included active suspension developed from the Citroen SM and aviation-type carbon brakes, but the costs were prohibitive.

In keeping with Artioli’s grand plans, the EB110 was launched with 2000 guests at Paris’ Place de La Defense on 14 September 1991, the day before the 110th anniversary of Ettore’s birth. It was presented by actor Alain Delon.

The UK launch (4 Feb 1993) began early when an EB110 left Grosvenor House for an appointment with Chris Evans on The Big Breakfast. At 10am, 24 vintage Bugs led two 110s around Hyde Park. Guests at dinner included Ettore’s youngest son Michel and pre-war agent Jack Lemon-Burton.

Gildo Pastor, who bought the cars and spares at the bankruptcy sale, entered a modified EB110 for Le Mans in 1996, with Patrick Tambay and Derek Hill, but the French GP qualifying. Pastor also ran the car in the USA.

| Car |

Bugatti EB110 GT (SS) |

| Made as | Italy |

|

Sold |

1992-1995 |

| Number built | 123 (all coupes) |

| Construction |

carbonfibre/Kevlar body bonded to carbonfibre tub, with integral rollcage |

| Engine |

all-alloy, qohc 60v 3500cc V12, with four IHI turbochargers and intercoolers, Bugatti/Weber fuel injection; |

| Max power | 553bhp @ 8000rpm (603bhp @ 8250rpm) |

| Max torque |

451lb ft @ 3750rpm (479lb ft @ 4250rpm) |

| Transmission | six-speed manual, 4WD |

| Suspension |

independent, by wishbones, coils, adjustable gas-filled dampers, anti-roll bars |

| Steering |

power-assisted rack and pinion |

| Brakes |

ventilated discs, with servo and ABS |

| Measurements |

Length 14ft 5in (4400mm) Width 6ft 4in (1940mm) (6ft 5 1/4in (1960mm) Height 3ft 81/4in (1125mm) Wheelbase 8ft 4in (2550mm) |

| Weight | 3430lb (1566kg) (3462lb (1570kg)) |

| 0-60mph |

0-60mph 4.5 secs (3.1 secs) |

| Top speed |

212mph (218mph) |

| Mpg |

18.8 |

| Price new |

£285,500 (£281,000) |

| Price now |

£180-230,000 (£370-410,000) |