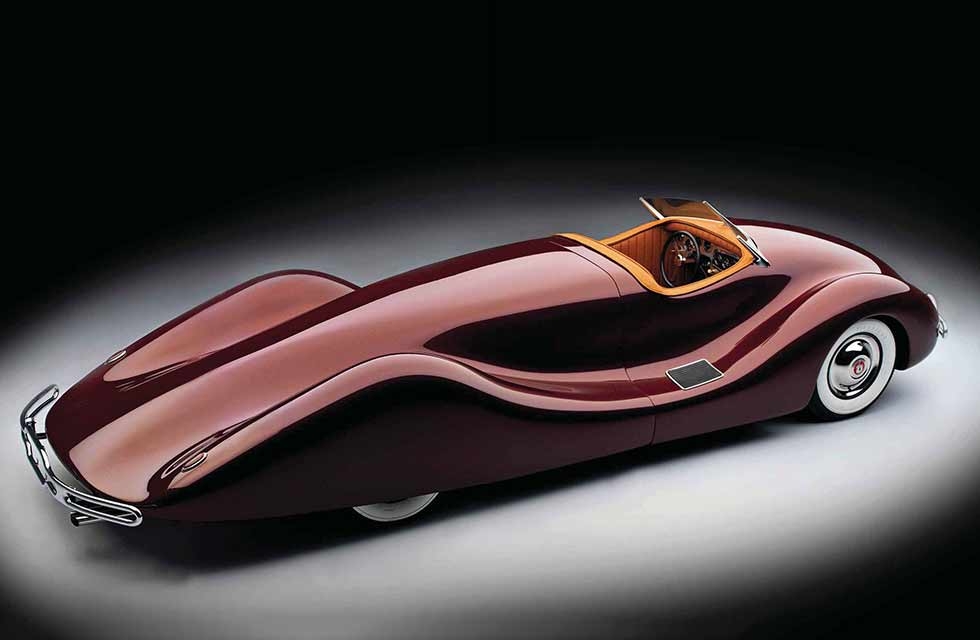

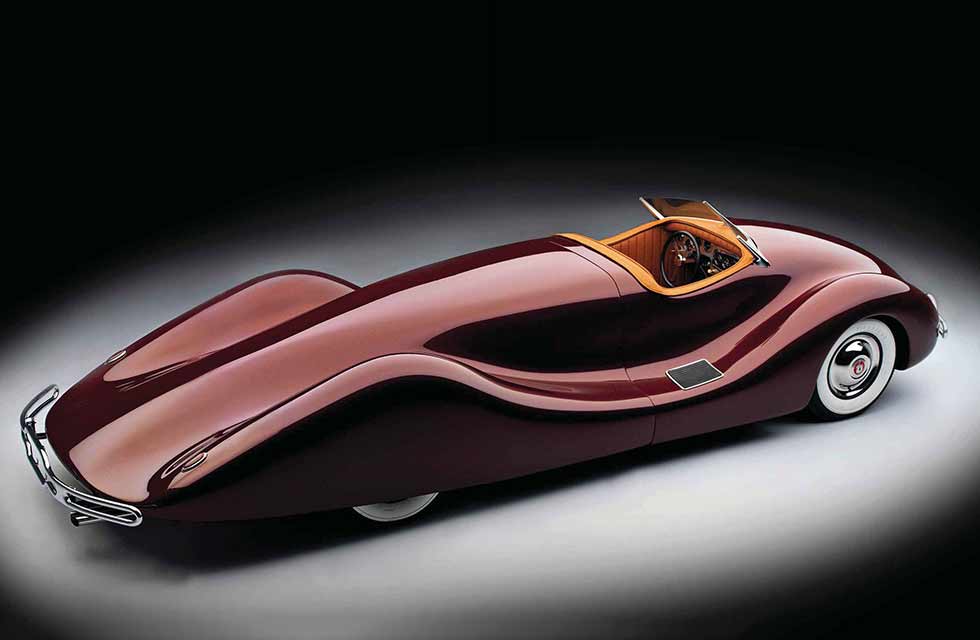

Timbs Special Newly resurfaced beauty of the post-war custom craze. A seamless restoration. The Timbs Special caused shockwaves in the late 1940s and then disappeared into obscurity. Now it’s back in the limelight and wowing the crowds again. Words Ken Gross. Photography Peter Harholdt.

At the 2012 Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance, a sleek rear-engined car appeared that few recognised. Voluptuous and stunning, this one-of-a-kind roadster was first seen more than 68 years ago. Designed by Norman Timbs, a talented mechanical engineer who lived in Van Nuys, California, it starred on the cover of Motor Trend, then America’s newest car magazine. To appreciate its impact, let’s look back on the exciting era in which it was created.

Civilian auto production ceased in America in February 1942. Four years later, after war’s end, there was immense demand for new cars from a population starved of them. With new models in short supply, the talented few customised and updated pre-war cars.

‘It was purchased by a prop man for a Hollywood studio and appeared in the Nicolas Gage film Gone in 60 Seconds’

Customising techniques were first made popular in Dan Post’s Blue Book of Custom Cars, along with numerous Fawcett Publications one-off paperbacks, and when Robert E ‘Pete’ Petersen’s magazine empire took flight, Hot Rod, Car Craft, Rod & Custom and Motor Trend chronicled the burgeoning custom car scene.

Some talented men designed their cars from the ground up, usually (but not always) using modified proprietary chassis, along with production engines. They’d build one car for their personal use, and that vehicle, if it were sufficiently striking, might appear in a magazine along with information detailing how it was conceived and constructed.

Dan Post called these vehicles sport customs. The ‘sport’ was something of a misnomer. Sport customs were largely boulevard cruisers. Softly sprung, heavy, and seldom equipped with modified engines, they were certainly not road racers. Still, if you couldn’t afford a Jaguar XK120 or a ‘Healey but could build a car from scratch, constructing a sport custom was the perfect solution.

While many of these custom creations were backyard efforts with basic engineering, Norman Timbs’ roadster was decidedly different. So was Mr Timbs, a skilled mechanical engineer who’d earlier designed the 1947-1948-1949 Indy 500-winning Blue Crown Specials, and who had worked for Preston Tucker on the Tucker 48 Torpedo design.

‘When most production models were still relatively tall and boxy, the roadster resembled a car from outer space’

Timbs’ radical roadster was featured on the cover of the second issue of Motor Trend in October 1949. A lovely female model, standing behind the car, posed in the driveway of a then-contemporary ranch house. The Timbs Special’s tapered tail extended towards the camera. Graceful and curvaceous, its shape was in stunning contrast to the era’s upright domestic cars.

Features included skirted fadeaway fenders, a contoured cockpit without doors, a split windshield, ‘siamesed’ dual exhaust tailpipes, and ‘1939 Ford teardrop taillights. Its 15in wheels were shod with whitewall tyres and hubcaps that resembled Cadillac ‘sombreros’.

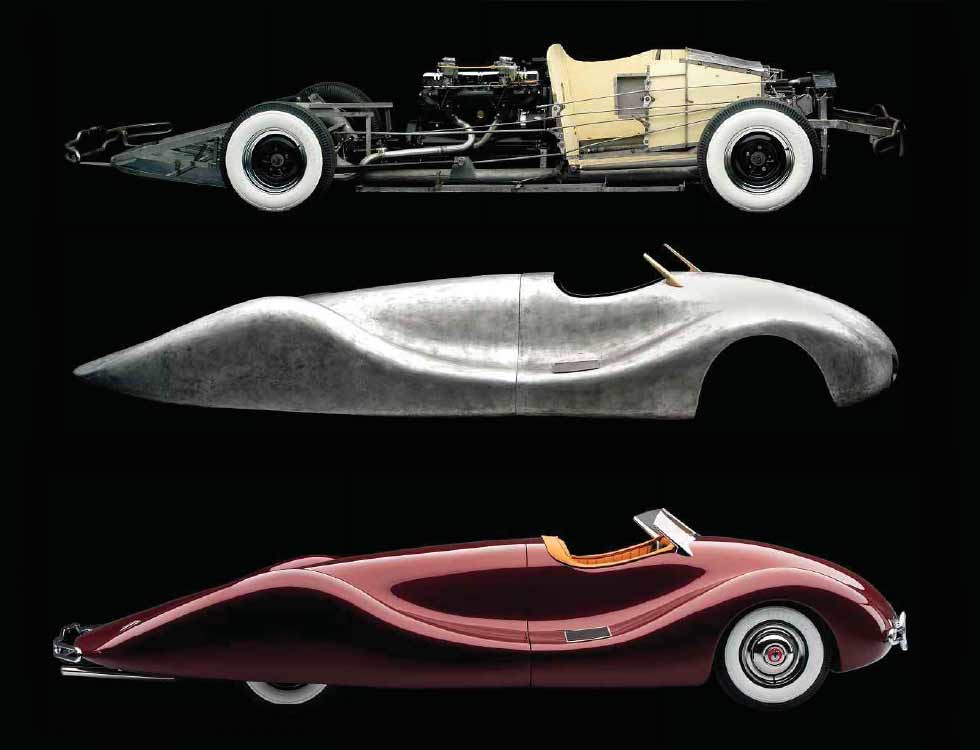

Early Motor Trends had sepia covers with black-and-white illustrations, so readers couldn’t appreciate the Timbs roadster’s deep, Titian red-maroon finish, speckled with gold flake, but they must have been impressed by its futuristic appearance. Volkswagen, Porsche, Tatra, the Renault 4CV and the ill- fated Tucker had rear engines, but that configuration was still comparatively rare. The Timbs roadster’s massive aluminium tail was hinged just behind the cockpit and opened on a single hydraulic ram to reveal a 320ci 1947 Buick straight-eight fitted with dual carburettors. Timbs reportedly ordered the ‘Compound Carburetion’ powerplant as a ‘crate motor’ from an LA Buick dealer. The straight-eight was located nearly in the centre of the car’s chassis, with a spare wheel and tyre mounted directly behind it.

The Timbs chassis was formed with 4in-diameter chromoly tubing, capped at the ends so the trapped air could be pressurised by an on-board compressor for the car’s massive horns. The solid front axle was a Ford I-beam, while the independent rear suspension consisted of a custom-made Timbs-designed swing axle with a Packard centre section and modified Ford rear axle bells.

Accessible via step plates, the cockpit could have emanated from a luxury speedboat. A Stewart-Wamer five-gauge accessory panel displayed a 5000rpm tachometer. Other instruments included an Echlin fuel gauge, a speedometer, gauges for vacuum, air and oil pressure, and fuel and water temperature, and an ammeter. There was a wood-rimmed three-spoke accessory wheel, and a column- mounted Ford shift lever. The cockpit, dash surrounds, door panels and seat were resplendent in tan leather. No roof was fitted.

The entire front end of the roadster was a single curvaceous piece, with a chromed grille reminiscent of a Cisitalia’s, flanked by a pair of low-mounted inset headlights, in turn framed by a plated nerf bar that echoed the shape of a similar two-plane unit on the rear. There were no doors; the only visible cutline was the vertical break behind the cockpit that separated the tail section.

The car appeared to be moulded in one continuous form and a bellypan helped aerodynamic efficiency. The overall effect was startling and for 1949, when most production models were still relatively tall and boxy, it resembled a car from outer space. It was inspired by the ill-fated Auto Union high-speed record-setter, driven by German driving ace Bernd Rosemeyer.

Using quaint language typical of the ’40s, Motor Trend described the Timbs roadster as ‘an unusually streamlined maroon job’. The car took three years to construct, at a cost of over $10,000. It was said to be 17.5ft long, on a 117in wheelbase and with a 56in track. It weighed 2500lb (1134kg).

The roadster appeared at several shows to great acclaim. Norman Timbs Jr, son of the builder, told me that his father ‘was very proud of it, and he compiled an elaborate scrapbook, but it was so futuristic, he couldn’t drive it anywhere without people constantly stopping and staring at it. It happened so often, he got tired of it.’

So Timbs decided to sell his roadster. Calling it a ‘two-seater sports’, he advertised it in Road & Track in February 1950 for $7500. The ad ran a photo of Timbs towering over his low-slung two-seater, claimed that the car was ‘capable of over 100mph’ and stated it ‘had been driven less than 5000 miles’.

By 1952, the Timbs Special was owned by Air Force Captain Jim Davis of Manhattan Beach, California. Wayne Thoms wrote about the car in the February 1954 issue of Motor Life. In photographs, it appeared to have been repainted in a lighter colour. Thoms’ article stated that the hand-formed aluminium body – built in sections on a wooden buck, then welded together – had been crafted by LA-area race car fabricator Emil Diedt.

Norman Timbs Jr believes that the body was built at California Coachworks. Emil Diedt worked there for a time, hence the connection. But Timbs Jr told me that there’s no proof Emil Diedt actually worked on the car. That said, the body workmanship was excellent, as was Diedt’s. It remains a mystery.

Motor Life stated ‘the performance is almost as fantastic as the appearance’; that the Buick engine ‘had been hopped up to develop in the region of 200bhp’; and ‘a top speed of 120mph should be no problem’.

Thoms commented: ‘Fortunately this car has the essential ingredients – precise steering, flat cornering, positive brakes – all necessary safety factors which are too important to overlook. Suspension is through conventional transverse leaf springs all around. The rear axle assembly provides independent suspension for the rear wheels, needed because the engine, transmission and differential are in line, virtually as a unit, with no driveshaft separating transmission and rear end. If this is confusing, remember that the engine is in the rear; the only thing in front of the driver and passenger being the radiator which, incidentally, mounts a small electric fan for auxiliary cooling.’

Norman Timbs Jr adds: ‘The bumpers were an afterthought. When dad tried to register it, the California DMV insisted on bumpers, so Bruce Bromme Sr, who’d built Indy race cars with his dad Louis, fabricated them.’

The ex-Timbs two-seater had several subsequent owners; it reportedly appeared in a TV episode of Buck Rogers, and it was displayed for years at the Halfway House restaurant in Saugus, California, where children played and jumped on its fragile aluminium body. After being stored outside near the Antelope Valley town of Gorman in California’s high desert, it was purchased by a prop man for a Hollywood studio and appeared in the Nicolas Cage film Gone in 60 Seconds. Then, left to moulder in the sun, the Timbs Special deserved a better fate.

I first saw the Timbs Special at the Petersen Automotive Museum prior to a 2002 Barrett- Jackson Auction. Having been abandoned to the elements, it was in rough shape. Gary Cerveny bought it for $17,200. ‘I didn’t know about the car until I saw it at the auction,’ he says. ‘It looked intriguing. When it didn’t seem to be selling, I decided to bid.’

Cerveny simply wanted the soon-to-be- restored Timbs roadster to be a good driver, but ensuing publicity convinced him that it was important, and deserved a first-class restoration. ‘I’d restored a belly tank,’ he recalls, ‘and as most of the Timbs car was all there, I mistakenly thought it’d be an easy restoration.’ After he and his dad performed much of the engine work and began on the body, Cerveny realised that ‘as the process went along, it was more complicated than I thought. I was in over my head.’ Collector Roger Morrison recommended that Gary send the car to Dave Crouse’s Custom Auto in Loveland, Colorado.

Crouse, who has restored several important historic hot rods, admits the restoration ‘was very difficult. This car was built as a concept exercise, so we had to do a lot of work to make it function properly.’ Other problems also came to light. ‘A previous owner cut a large square hole in the rear section to access the engine. He also cut open the wheel wells to change the rear tyres. Workmanship on the body was first rate, but there were no stiffening members to help the body retain its shape.’

‘This car is a monster to work on,’ Crouse continues. ‘The nose is fixed; there’s no hood, and the radiator is in front, with an expansion tank behind the cockpit bulkhead. Most linkages and controls are aircraft bell cranks. A few were missing; some didn’t work very well. The throttle and clutch linkages were re-engineered; we drove the completed chassis around to ensure everything worked before we mounted the body on it. Our intent was to build a show car, but make it drivable. The original workmanship is incredible.’

The suspension is ingenious too, but had been altered by a previous owner. ‘The geometry wasn’t right so, to make it work, someone kept adding more springs. We installed the regular Ford semi-elliptic spring pack and used air shocks, powered by the car’s compressor. It works beautifully.’

Crouse believes that magazine descriptions which suggest that air from the on-board compressor would be used to stiffen the chassis by being pumped into the tubular frame under pressure are wrong. ‘You’d need 1000psi or more before you’d notice much change,’ he says. ‘That said, Norman Timbs was ahead of his time. He worked with the best race car fabricators, and it shows. The welds and the machine work are gorgeous.’

That didn’t make the job any easier, however. ‘After we had the shape corrected, the surface preparation took forever. To obtain a straight, even parting line, we had the tail section on and off. It’s so big you can’t reach across it, so we built a scaffold to work on it. Sometimes you’ve got to get creative.’

That approach applied equally to the paintwork, too. Says Crouse: ‘We had a little chip of the paint from a kart that Timbs had built for his nephews. Gary Cerveny took it to noted hot rod painter Stan Betz, who experimented with several shades, and then mixed the correct colour with the right gold flakes. We sprayed it on in several steps, from base, to colour, to clear finish.’

Other tasks took detective work. ‘There’s a small pressure gauge on the left and we used a magnifying glass to identify it. It had a crimped bezel. Pat Swanson, an instrument expert from the Pacific Northwest, told us it was an Echlin 0-10psi mechanical fuel pressure gauge. He gave one to us to restore. The hubcaps are Lyons accessory items. It took years before we found a set.’

Gary Cerveny, who rebuilt the engine, reports that two cylinders had water in them so, retaining the original block, he installed a pair of cylinder sleeves. The crosshatches from the factory bore honing were still visible, and the pair of factory cast-iron exhaust headers empty into side-by-side Smithy’s mufflers, resulting in a rumble from the tailpipes.

‘You don’t find a car like this very often,’ Crouse says, ‘but I can’t credit Gary enough. Whenever there was a crunch, he stepped up and we went for quality.’

Timbs Jr, who displays a framed Motor Trend cover in his office, had spent time looking for the car but was unable to buy it. ‘The guy who owned it up in Gorman had visions of grandeur. Luckily, dad had saved his scrapbook, so there was a picture history for the restorers. I’m very glad that someone with the means to restore it properly has done it.’

The long-lost Norman Timbs Special won a Corporate award at the Amelia Island Concours d’Elegance in March 2010, then awaited a call from Pebble Beach. There the Timbs Special was in tough class competition, yet people were stunned by its audacious shape, as well as its clever engineering, exquisite restoration and palpable presence.

The Cervenys carefully trailered the car up from LA. ‘There’s no really good way to tie it down,’ says Gary, ‘so I never went over 50mph. It was a long ride, but winning was worth it.’

Spectators gathered around the Timbs Special all day, while Gary and Diane Cerveny told the car’s story again and again. When the sport custom class was called to the ramp, the Norman Timbs Special had won the coveted first-in-class trophy. The long, low roadster rumbled up and slowly crossed the display ramp. Gary and Diane Cerveny enthused: ‘We were thrilled. This is the highlight of our vehicle showing hobby. It was a special day for us and the Timbs.’

Honoured on both US coasts, the Timbs roadster remains a tribute to the vision of its creator and the skills of its restorers.

TECHNICAL DATA FILE SPECIFICATIONS 1949 TIMBS SPECIAL ROADSTER

ENGINE 5244cc (320ci) straight-eight, OHV, twin carburettors

MAX POWER 200bhp @ 4200rpm (claimed)

MAX TORQUE 368lb ft @ 2500rpm (claimed)

TRANSMISSION Three-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

SUSPENSION

Front: beam axle, transverse leaf spring, pneumatic dampers.

Rear: independent, swing axles, transverse leaf spring, pneumatic dampers

BRAKES Drums

WEIGHT 1134kg

PERFORMANCE

Top speed 100mph+

0-62 11.5sec

AN UNHERALDED GENIUS

The Timbs roadster was a piece of artistry from, the pen of a man who was actually more engineer than stylist.

Norm Timbs studied mechanical engineering at USC, then rose to the rank of chief engineer at Halibrand Engineering, where he designed wheels, disc brakes and more.

Timbs also designed the front-wheel-drive, Offenhauser-powered Blue Crown Spark Plug Specials, driven by Bill Holland and Mauri Rose, that won the Indianapolis 500 an unprecedented three times in 1946, 1947 and 1948; the Howard Keck front-drive Special, which competed in the Indy 500 from 1946 to 1950, driven by Jimmy Jackson and Mauri Rose; and the original 1952 Howard Keck (Superior Oil Company) Fuel Injection Special, which led the 500 for two-thirds of the race on its maiden appearance. His 1952 pole-setting JC Agajanian Cummins Diesel Special pioneered the lay-down engine configuration.

Timbs was responsible for the Edwards Ford V8-powered special, successfully campaigned by Sterling Edwards in the 1948-1949 SCCA racing season. It featured an aluminium monocoque rear section and a spaceframe-type subframe, like the later Jaguar E-type. His pioneering design for the Halibrand Shrike racecar used a cast magnesium monocoque chassis.

Timbs understood the use of negative aerodynamic pressure to enable downforce at high speeds; his advanced aerodynamic work for the Howard Keck Streamliner was done in the Cal-Tech wind tunnel. It was the first Indianapolis car to employ ground-effect aerodynamics.

Timbs Jr says his father also developed an advanced hydroplane design for Howard Keck, using two propellers to minimise the cavitation effect a single-screw design encounters when the hull lifts out of the water.

Timbs passed away in 1993 at the age of 76. His son Norman Jr also became an engineer. Looking back, it’s hardly surprising the Timbs Special made such an impact.