Rolls-Royce Phantom Wartime saga of Montgomery’s staff car. ‘Nobody ever won a war at 30mph’ So said General Eisenhower of a Rolls-Royce Phantom that became the post-war daily drive of Field Marshall Montgomery. This is its extraordinary story. Words David Burgess-Wise. Photography Tim Andrew.

MONTGOMERY’S PHANTOM

There’s a wartime story concerning this remarkable Rolls-Royce Phantom III that bears repeating. Its long-term chauffeur Percy Parker was flagged down by a policeman in London’s East End and accused of exceeding the speed limit. The constable was reaching for his notebook when the rear window was wound down and a Kansan voice sharply informed the policeman: ‘Nobody ever won a war at 30mph.’ It was Five-Star General Dwight D Eisenhower, Commander-in-Chief of the Allied Forces in Europe, for once not being driven by the delicious Kay Summersby. Suitably chastised, the constable waved the Phantom on its way. Eisenhower was not to be this Rolls- Royce’s only famous wartime associate.

The Mulliner-bodied Phantom III, chassis 3AX79, had been ordered from John Croall & Sons of Edinburgh in late 1936 by Alan Samuel Butler, chairman of De Havilland Aircraft; possibly he had attended the Scottish Motor Show in Glasgow’s Kelvin Hall, where Croall had shown a 25/30 and a Phantom III, bodied by Mulliner, a company in which it had held a controlling interest since 1909.

Butler was a Rolls-Royce aficionado, having owned a 20hp, three New Phantoms, two Phantom IIs and 3½-litre and 4¼-litre Derby Bentleys. This Old Etonian’s family fortune came from tar distillation, along with coal and coke works in Bristol and Gloucester which, among other things, supplied the local town gas. During the Great War he had graduated from Sandhurst and joined the Coldstream Guards, but the Armistice was signed before he could be drafted to France. In 1919 he was stationed on Wimbledon Common, not far from Colonel GLP Henderson’s flying school at Hounslow, where he learned to fly an Avro 504 powered by a Gnome Monosoupape rotary engine.

{module Autoads}

In 1920, Butler bought a Bristol Type 29 two-seater biplane, a derivative of the wartime Bristol Fighter, and passed the test for his pilot’s licence at the Bristol Flying School the year after. He became the first British private owner to tour Britain and the Continent by air, and commissioned a fast touring aircraft to replace the Bristol from the De Havilland Aircraft Company. Finished in 1922 at a cost of £3500, Butler’s new DH37 was named Sylvia after his sister, and so successfully met his requirements that he invested £10,000 in De Havilland, a gesture that enabled the company to buy the Stag Lane aerodrome, which became its base until it moved to Hatfield in 1934.

‘This Phantom III had a body like no other. Tests showed that wind resistance was reduced by 15%’

Butler became chairman of De Havilland in 1924, and became close friends with Geoffrey de Havilland, who recalled: ‘Unlike many rich men, Alan Butler tried to spend and invest his money wisely and was usually successful. He flew whenever possible in British as well as in European competitions, in 1928 obtained the world speed record for light two-seater machines, and flew to the Cape with his wife, Lois, herself a pilot. As well as his accomplishments in the air, he was greatly interested in the sea and sailing. He held a yacht master’s certificate and sailed his own yacht, Sylvia, four times across the Atlantic. Butler gave the impression of having great reserves of nervous energy, which he sometimes used with a single-minded ruthlessness that led to overwork and illness. But he also had a keen sense of humour and was a delightful companion.’

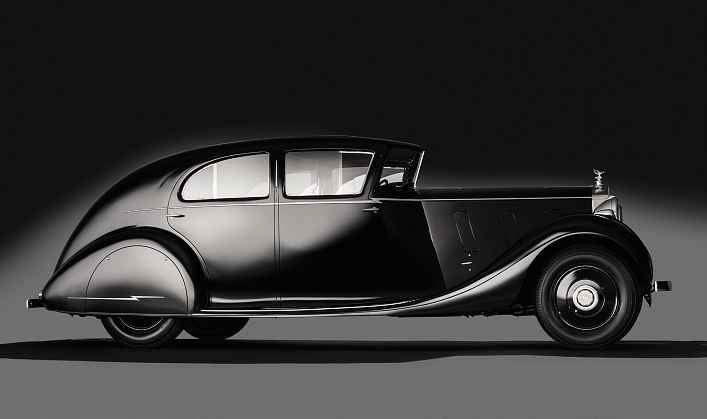

The Phantom III that Butler commissioned from Croall had a limousine body like no other. Using his knowledge of aerodynamics, Butler had concluded that a forward-raked, vee-shaped windscreen conferred a number of advantages. He claimed that tests in the De Havilland wind tunnel showed that wind resistance was reduced by up to 15%, while the reverse angle also helped to reduce dazzle at night and removed water from the windscreen in bad weather.

Curiously, no De Havilland aircraft ever had a reverserake windscreen, though it appeared on a number of fast single-engine monoplanes built by the rival Miles company, Falcon, Whitney Straight and Nighthawk among them. It’s possible that Butler had been taken by this feature when, in September 1935, De Havilland’s Hatfield aerodrome hosted the start and finish of the King’s Cup air race, in which the winning Miles Falcon Six and several other Miles planes had reverse-rake ’screens. Blossom Miles herself had claimed ‘a 5mph increase over standard speed’.

A road trip in the car proves the merit of its unorthodox appearance. At the wheel is Paul Wood of Rolls-Royce Heritage specialist P&A Wood, which has prepared the Phantom for Rolls-Royce’s ‘The Great Eight Phantoms’ exhibition to launch the new model, and also for Pebble Beach. ‘The advantages are the clear visibility and lack of glare. There’s a wonderful view over the front of the car – you can see the edges and know exactly where you are on the road. It’s certainly better than most Phantoms.’

Off test at Derby on 16 November 1936, the Phantom III chassis (with low ‘F’ rake steering column position) was delivered to Mulliner four days later from Rolls-Royce’s London depot at Lillie Hall, Fulham. The build sheet had been made out on 29 October: ‘Body: 4 door 4 light saloon with special VEE front sloped windscreen and swept tail. Fade away ridge along roof.’

‘The list of distinguished passengers would be hard to match, including King George VI, Winston Churchill, Eisenhower…’

From the A-pillar back, Butler’s Rolls-Royce followed airline fashion, with a tapering tail that housed the spare wheel in the bootlid. There were spats on the rear wheelarches with chrome flashes like stylised lightning bolts. The body, it was claimed, had been designed by Geoffrey de Havilland himself. It added £970 to the chassis price of £1480. An aviation touch was the Smiths aneroid altimeter reading to 7000ft in the fully instrumented dashboard. The finished car was delivered to Butler on 8 February 1937, bearing the London registration DUV 553.

Butler was a staunch patriot so, in 1940, soon after war was declared, he offered his Phantom III to the War Office on three conditions: that it was not to be sent abroad; that it was to be driven, as it had been in his service, by a Rolls-Royce trained driver; that Rolls-Royce was to carry out scheduled inspections and any necessary repairs.

And so the Phantom III, given the Army registration 16 YF 66, would be reserved for the use of the Chief of the Imperial General Staff – the professional head of the British Army – and was allocated to the 6ft 4in General Sir William ‘Tiny’ Ironside, who retained its use after Churchill had relieved him of his post after the fall back on Dunkirk in May 1940 and put him in charge of Home Forces.

It was at this point that the Phantom met the man who was to drive it for the next six years, Sergeant Percy Parker, who recalled: ‘Scrambling back from Dunkirk, I was instructed by telegram to report to Kneller Hall, to once again drive General Ironside.’ Parker, the holder of a Rolls- Royce Certificate of Merit as driver and mechanic, had been the last man out of France after World War One, escorting the body of the Unknown Warrior, and the first man into France in World War Two. Between the wars he had been chauffeur to Queen Alexandra, who died in 1925, still using the 14hp Renault that she had been supplied with by Stratton & Instone in 1906; he also drove her unmarried daughter Princess Victoria, who died in 1935.

Ironside’s plan for the defence of Britain met with much criticism, and after less than two months in the job he was summoned to the War Office and told that he was to be replaced by General Sir Alan Brooke. He left without meeting Brooke, and left him no information save for a brief memo noting that he had arranged for Brooke to take over the use of the Phantom III as his staff car. Parker recalled: ‘Sir Alan willingly accepted the Phantom and my services, and we remained with him until his retirement in 1946.’

That encompassed Brooke’s promotion to Chief of the Imperial General Staff on Christmas Day 1941, a role he would occupy until his retirement. Parker’s memoirs thus kick into the long grass several of the stories that have accumulated around such a historic car over the years. One says that ‘a year or so later it would be used by Field Marshal Viscount Gort, who was Commander in Chief of the UK Home Forces’; since at the time Lord Gort was Governor of the embattled island of Malta, having previously been Governor of Gibraltar, that was hardly likely. Nor does the story that the car was allocated to General Montgomery on the eve of D-Day stand up, even though Monty was to take the car over after the war ended. The Rolls-Royce that he took to Normandy on D-Day plus 3 in June 1944 was a Wraith, chassis WMB40, its driver Percy Parker’s younger brother Cedric. It’s unlikely, too, that there’s any substance to the tale that the Phantom was the second Allied car to enter Berlin after the fall of the Third Reich.

‘Its itinerary included such addresses as 10 Downing Street, Chequers, the War Office, NATO Command HQ…’

But in Alan Brooke’s tenure it had a list of distinguished passengers that would be hard to match, including King George VI, Winston Churchill, Ike of course, and the Prime Ministers of Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Who knows what wartime secrets were discussed in its rear compartment, with the division window wound up to keep chauffeur Percy from being a nosy Parker?

Churchill could be a difficult passenger, remembered Percy Parker: driving from London to Chequers on a pitch-dark night, he urged impatiently: ‘Can’t you go any faster?’ Parker thought quickly, changed into a lower gear and revved the engine to give the impression that the car was going faster. Churchill was fooled: ‘Do you want to break our bloody necks?’ he growled.

On another occasion, Parker was driving General Brooke and the First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Dudley Pound, back in the moonlight from a meeting at Chequers. Both men were fast asleep in the back when, near Northolt, ‘there was a swishing sound as though something was coming up behind’, followed by a tremendous explosion a few yards away that blew the Phantom onto the grass verge. The only response from the back came from the Admiral: ‘Who rocked the boat?’ said his sleepy voice.

One of Brooke’s first outings in the Phantom was for lunch at Windsor Castle with the Royal Family, to discuss with the King the details of the defence of Windsor. As they left the castle, Brooke asked Parker whether he had been given his lunch. ‘Oh, yes,’ replied Parker, ‘I know my way around the castle well from former visits. What is more, I have come away with a spare chamois and sponge: they keep the best chamois and sponge you can get anywhere.’

When Brooke – by then Viscount Alanbrooke – retired in 1946, the Phantom was offered back to Alan Butler, who said that as the car had by then covered 300,000 miles he had no further use for it, and asked the War Office to make him a reasonable offer. This was accepted, and the Phantom was assigned to Britain’s best-known wartime general, Field Marshal Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, the new Chief of the Imperial General Staff. He kept the Phantom as his staff car after relinquishing his post in 1948 and taking on the role of chairman of the Western Union of Commanders-in-Chief (1948-1951), the forerunner of NATO, of which he was Deputy Supreme Commander in Europe until his retirement.

During those years, its itinerary included such addresses as 10 Downing Street, Chequers, the War Office in Whitehall, NATO Eastern Command HQ at Northwood, and the NATO Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers- Europe at Camp Voluceau in Rocquencourt, near Versailles.

Rolls-Royce historian Tom Clarke notes: ‘As Monty neared retirement, he made strenuous efforts to keep the Phantom III, 3AX79. It was not a wartime car for him, but its role while he was CIGS in the early post-war years made him “very attached to the car”, so too his driver of the last 12 years. In fact, the Secretary of State at the War Office, John Hare, had agreed at some time prior to Monty’s retirement that he could have the car at full market value.’

Not only that, but Rolls-Royce had offered Monty a free overhaul should he eventually acquire it. Inevitably, the Civil Service dragged its heels in trying to secure an agreed valuation, the to-and-fro of correspondence lasting from November 1957 to September the following year, with dealer Jack Barclay reckoning the Phantom III might sell for between £500-£1000 given its link with Monty, while other dealers and Rolls-Royce arrived at a valuation (‘personal association’ not included) of £500.

In the meantime, says Clarke: ‘Monty’s good fortune doubled in May 1958 when a full mechanical refurbishment was authorised costing £450… that brought the amount spent on the car in 2½ years to £1650!’

In the end, when Monty retired in 1958, he bought the Phantom from the War Office for £300, retaining the services of his long-term driver Cedric Parker (Percy’s brother), and kept the car in an only-just-big-enough Marley concrete garage at his home at Isington Mill, near Alton in Hampshire, alongside a wooden building containing the three caravans that he had used as mobile headquarters during the campaign in North West Europe. After Cedric Parker died in 1962, Monty found it difficult to find another chauffeur, so in 1963 he sold the Phantom. Chauffeurless, Monty drove his Daimler Conquest Century, an ex-works demonstrator that he had bought in 1954 and kept for 13 years – usually driving slowly down the centre of the road followed by a queue of impatient drivers.

In July 1963 London dealer Jack Compton placed the followingsmalladinAutocar:‘1937PIII,fittedaerodynamic saloon body by Mulliner, chassis and engine fully modified, maintained regardless of cost by makers from new, late property of well-known Field Marshal: £2000.’

That was something like three or four times as much as other PIIIs were selling for at the time, and the mileage of some 340,000 was certainly excessive. The jolie laide Phantom was obviously slow to sell, and the advert remained in Autocar for weeks, with the car finally being described as ‘the most fabulous PIII on the market today’.

The eventual purchaser came from the far side of the Atlantic, a man called George Beaumont, who after a year sold it to Drew Wilson. There followed a succession of owners, including collector-cum-auctioneer James Leake of Muskogee, Oklahoma, who claimed to have the largest private collection of Rolls-Royces in the world. He displayed the car for more than 10 years before selling it to Herbert Dorner of Northfield, Illinois. The Phantom returned to Europe in 2010, after being bought through Gooding & Co by the current owners, Catherine and Henry Robet.

The Robets initially placed the Phantom III with P&A Wood for a road test and workshop report, but, as the inspection continued, more and more areas of concern revealed themselves. At that point, the decision was taken that all work carried out should be completed to a concours standard, and a thorough restoration began, with its goal the retention of as much originality as possible.

Much of the work necessary was consistent with the car’s high mileage – a corroded exhaust system, sludge in the cooling system, a seized cardan shaft coupling, a worn-out oil pump needing new gears, complete rewiring – but the ash body framing was perilously deteriorated, and whole sections of the body, door and bootlid framework needed to be replaced. The structure of the running boards also needed repair and replacement. Some of the body panels also needed to be remade, and the car was then carefully repainted to look as it did when delivered to Alan Butler in 1937.

Happily, the interior leather trim merely needed sympathetic restoration, and the wood trim – fascias and cappings – was adorned with new silver inlays. During this process, Paul Wood noticed a burn mark on one of the cappings. ‘We’ll have to bleach that out,’ he told the owner. ‘On no account,’ came the reply. ‘That’s where Winston Churchill used to stub out his cigars!’

THANKS TO P&A Wood, www.pa-wood.co.uk. The Great Eight Phantoms exhibition runs from 27 July to 2 August, 10am to 5pm, at Bonhams, New Bond Street, London W1S 1SR.

TECHNICAL DATA FILE SPECIFICATIONS 1937 Rolls-Royce Phantom III

Engine 7340cc V12, OHV, dual-downdraught Rolls-Royce Zenith carburettor

Max power 165bhp @ 3000rpm / DIN

Max torque 299Ib ft @ 1900rpm / DIN

Transmission Four-speed manual (synchromesh on 2,3,4), rear-wheel drive

Steering Marles cam and roller

Suspension Front: double wishbones, coil springs, hydraulic dampers. Rear: live axle, leaf springs, hydraulic dampers, anti-roll bar

Brakes Cable-operated drums, servo-assisted

Weight 2642kg

Performance Top speed 92mph

Right Restoration work has been carried out in the Phantom’s exquisite interior, though a burn mark on one of the cappings remains as testament to one of Churchill’s cigars. Above from left Phantom was commissioned by an aviation enthusiast, hence the Smiths aneroid altimeter in the dash panel; windscreen is the most distinctive element, but the ‘swept tail’ treatment is characteristic of ‘airline’ styling. Left Field Marshall Montgomery visits Derby with his Phantom for a meeting with Lord Hives, former head of the Rolls-Royce Aero Engine division and chairman of Rolls-Royce Ltd.